Proximal and Total Femur Resection with Endoprosthetic Reconstruction

Jacob Bickels

Martin Malawer

BACKGROUND

The proximal and midfemur are common sites for primary bone sarcomas and metastatic tumors.

Patients who were candidates for extensive femoral resection because of malignant tumor had long been considered a high-risk group for limb-sparing procedures because of the extent of bone and soft tissue resections, the anticipated poor function postoperatively as well as the deleterious consequences of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Hip disarticulation or hemipelvectomy were, therefore, the classic treatment options for patients with large lesions of the proximal or midfemur. Both procedures were associated with a dismal functional, aesthetic, and psychological outcome.

Today, improved survival of patients with musculoskeletal malignancies, developments in bioengineering, and refinements in surgical technique have enabled the performance of limb-sparing procedures for these patients as well. Local tumor control is good, as is the probability of a functional extremity. Proximal and total femur resection became a reliable surgical option in the treatment of primary bone sarcomas and metastatic bone disease and, more recently, of a variety of nononcologic indications. These latter indications include failure of internal fixation, severe acute fractures with poor bone quality, failed total hip arthroplasty, chronic osteomyelitis, metabolic bone disease, and various congenital skeletal defects.1,4

Methods of skeletal reconstruction include resection arthrodesis, massive osteoarticular allograft, endoprosthetic reconstruction, and prosthetic allograft composites.2,3,5,7

Osteoarticular allografts, which were popular in the 1970s and 1980s, aim to restore the natural anatomy of a joint by matching the donor bone to the recipient’s anatomy, but they are associated with increased rates of infection, nonunion, instability, fracture, and subchondral collapse and thus ultimate failure.6,8

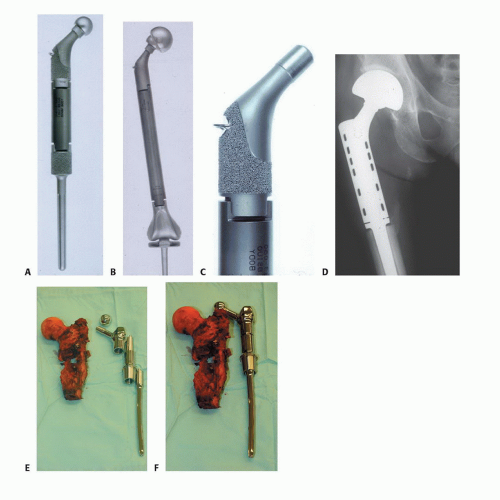

Introduced in the mid-1980s, modular prostheses revolutionized endoprosthetic reconstruction. The modular system enables the surgeon to measure the actual bone defect at the time of surgery and select the most appropriate components to use in reconstruction. Components of these interchangeable systems include articulating segments, bodies, and stems of varying lengths and diameters. Design features include extensive porous coating on the extracortical portion of the prostheses for bone and soft tissue fixation and metallic loops to assist in muscle reattachment (FIG 1).

Prosthetic reconstruction of the proximal and total femur has been shown to be associated with good function and minimal morbidity in the majority of the patients.1 Preservation of the joint capsule and reattachment of the abductor mechanism have also been shown to considerably decrease the rate of dislocations, which have traditionally been the most common complication of endoprosthetic reconstruction at that site.1

ANATOMY

Hip joint and joint capsule. The intracapsular location of the femoral neck makes it biologically possible for tumors of the proximal femur to spread into the hip and adjacent synovium, joint capsule, and ligamentum teres. The ligamentum teres provides a mechanism for transarticular skip metastases to the acetabulum. Fortunately, intra-articular involvement is rare and usually occurs after a pathologic fracture. The capsule can be preserved and an intra- articular resection of the femur is usually possible. In the case of capsular or acetabular involvement or both, extra-articular resection of the hip should be considered.

The greater trochanter, which is removed with the surgical specimen, serves as the attachment site for the hip abductors. The tendon stump should be marked and preserved for reattachment to the prosthesis.

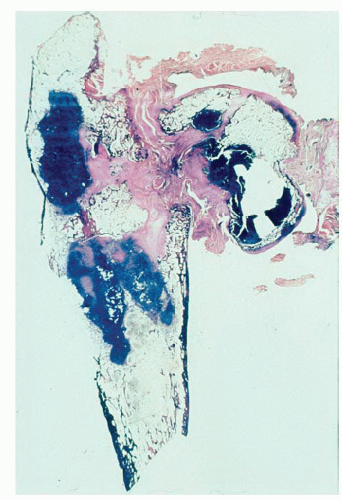

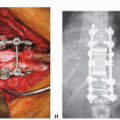

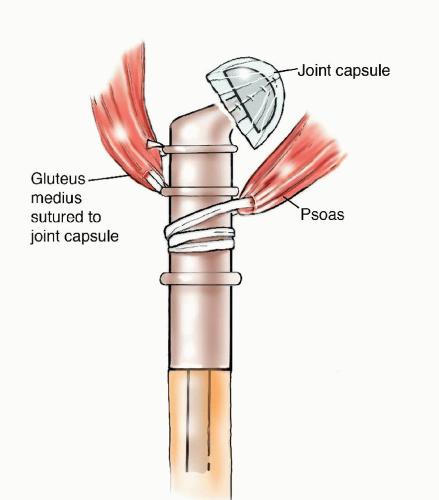

The lesser trochanter, which is removed with the surgical specimen, serves as the attachment site for the psoas muscle. The tendon stump should be marked and preserved for reattachment to the prosthesis. The combined attachment of the abductors and psoas to the lateral and medial aspects of the prosthesis, respectively, preserves balanced prosthetic range of motion (FIG 2).

The femoral artery descends the thigh almost vertically within the sartorial canal toward the adductor tubercle of the femur, enters the opening of Hunter canal at the adductor magnus muscle and becomes the popliteal artery. The profunda femoris artery branches to the medial aspect of the femoral artery 4 cm below the inguinal ligament. Occasionally, the profunda femoris is ligated and resected en bloc with large tumors of the proximal femur. Ligation of the profunda femoris in an adolescent patient with patent vasculature of the lower extremity is not expected to result in vascular compromise. However, preoperative angiography is strongly recommended in adults because ligation of the profunda femoris in the presence of an occluded superficial femoral artery may result in an ischemic extremity and the subsequent need for amputation.

FIG 2 • Combined attachment of the abductors and psoas to the medial and lateral aspects of the prosthesis, respectively, preserves balanced prosthetic range of motion.

The knee joint is seldom directly invaded by tumors of the femur that extend to its distal aspect. When it does occur, invasion is usually the result of a pathologic fracture, contamination of an improper biopsy technique, or tumor extension along the cruciate ligaments. The presence of hemarthrosis is suggestive of intra-articular disease, and intra-articular resection of the knee joint (ie, en bloc resection of the femur with the knee joint capsule and articular surface of the proximal tibia) should be considered in those cases.

INDICATIONS

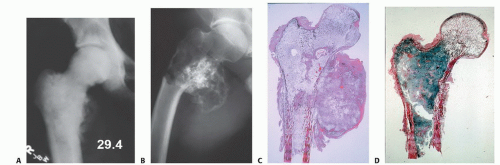

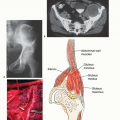

Primary bone sarcomas (FIG 3)

Benign aggressive tumors associated with extensive bone destruction (FIG 4)

Metastatic tumors associated with extensive bone destruction (FIG 5)

Nononcologic indications which include failure of internal fixation, severe acute fractures with poor bone quality, failed total hip arthroplasty with segmental bone loss below the level of the lesser trochanter, chronic osteomyelitis,

metabolic bone disease, and various congenital skeletal defects (FIG 6)

Proximal femur resection is performed for metaphyseal-diaphyseal lesions that (1) extend below the lesser trochanter, (2) cause extensive cortical destruction, and (3) spare at least 3 cm of the distal femoral diaphysis. Total femur resection is performed for diaphyseal lesions that (1) extend proximally to the lesser trochanter and distally to the distal diaphyseal-metaphyseal junction and (2) cause extensive bone destruction (FIG 7).

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

Proximal and total femur resections are major surgical procedures that necessitate an especially detailed preoperative evaluation. Physical examination and imaging studies are supposed to determine the following:

Extent of bone resection and dimensions of the required prosthesis

Extent of soft tissue resection and reconstruction possibilities

Proximity of the tumor to the femoral vessels, femoral nerve, and sciatic nerve

Most complications can be avoided by predicting their likelihood prior to surgery and modifying the surgical technique accordingly. A full range of imaging studies is needed, including plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the whole femur and the hip and knee joints. CT and plain radiography are used to evaluate the extent and level of bone destruction, and MR imaging is used to evaluate the medullary and extraosseous components of the tumor, intracapsular tumor extension, and the presence of skip metastases within the femoral canal and in the acetabulum.

Angiography of the iliofemoral vessels is essential prior to resection of tumors of the proximal femur. Vascular displacement is common when tumors have a large, medial extraosseous component: The profundus femoral artery is particularly vulnerable to distortion or, less commonly, to direct incorporation into the tumor mass. If the tumor has a large medial extraosseous component and ligation of the profundus femoral artery is anticipated, the presence of a patent superficial femoral artery must be documented by angiography prior to surgery. Preoperative embolization may be useful in preparation for resection of metastatic vascular carcinomas if an intralesional procedure is anticipated. Metastatic hypernephroma is an extreme example of a vascular lesion that may bleed extensively and cause exsanguination upon the execution of an intralesional procedure without prior embolization.

FIG 5 • Metastatic carcinoma of the proximal femur with a pathologic subtrochanteric fracture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|