BACKGROUND

A multidisciplinary team operating in a secondary or tertiary care setting is a commonly adopted model for the provision of pregnancy care to women with diabetes.1 Our own clinic started in the 1960s and our practice has evolved over the years in response to changes in patient population, clinical evidence, and local resources. It mirrors practice elsewhere in the UK. Here we offer simple practical advice on how to provide a diabetes pregnancy service meeting the standards recommended in the latest UK CEMACH report.2

GUIDELINES FOR THE PROVISION OF CARE

Cutchie and coworkers published a review of 12 international guidelines for the care of women with diabetes in pregnancy.3 Among women with known diabetes, the guidelines for preconception care are similar apart from folic acid doses varying between 0.4 and 5 mg daily. The guidelines for antenatal care rarely differentiate between patients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, but there are significant differences among the different guidelines in glycemic targets during pregnancy, frequency of antenatal appointments, ultrasound scans, and gestational age at induction or cesarean section. However, recommendations for labor and postnatal management are similar.

For gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), there is great variation within and between countries in the selection process for screening, screening methodology, and oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT), including number of samples taken and the diagnostic criteria. For example, the selection for screening varies from none, to specified groups only, to all women. Screening methodology includes a 50-g non-fasting OGTT performed between 24 and 28 weeks; a random serum glucose at 28 weeks; and a 75-g OGTT. Diagnostic criteria vary with fasting: values from 5.3 to 7.0 mmol/L (95–126 mg/dL) and/or 2-hour glucose from 7.8 to 11.1 mmol/L (140–200 mg/dL) following a 75-g oral glucose load.4,5

In the management of GDM areas of disagreement involve fasting glucose targets (5.5–6.0 mmol/L [99–108 mg/dL]), postprandial targets (1 or 2 h; <7.0–< 8.0 mmol/L [126–144 mg/dL]), timing of delivery (38 weeks to term), and timing of postnatal OGTT (4–26 weeks, but usually 6 weeks).5

There is therefore no international consensus on the management of women with diabetes in pregnancy, and especially for the diagnosis and management of GDM. These latter issues are addressed in chapter 6. The authors emphasize the advantages of a single international guideline based on consensus, best evidence, and best practice.

AIMS OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY JOINT METABOLIC ANTENATAL CARE

The overall aims are to allow the mother to have a good experience of pregnancy, excellent glycemic control, and normal delivery of a healthy baby

Prepregnancy care

The reader is referred to chapter 8. The barriers to achieving these aims are discussed in detail in the section below on Special needs.

Pregnancy care

The aims of pregnancy care for women with diabetes during pregnancy are:

- Referral to a combined (diabetes and obstetric care) antenatal clinic when pregnancy is suspected

- Maintenance of near-normal blood glucose levels throughout pregnancy if this can be achieved safely:

° Premeal capillary glucose levels 3.5–5.9mmol/L (63–106 mg/dL)

° 1-hour postprandial capillary glucose levels less than 7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dL)6

- Cessation of any potentially teratogenic medication:

° Patients are often prescribed statins and drugs affecting the renin angiotensin system prior to pregnancy

- Prescription of folic acid 5mg daily during the first trimester

- Detection, monitoring, and appropriate management of any diabetes-related complications

- Accurate pregnancy dating

- Early identif cation of fetal abnormalities

- Assessment of fetal well-being

- Determination of the most appropriate time and mode of delivery

- In women at high risk of preterm delivery, inhospital administration of steroids with hourly glucose monitoring and, if necessary, with intravenous insulin therapy

- Provision of patient-centered care and support appropriate to the patient’s educational, cultural, religious, and social background.

- Late referral due to inadequate patient education or compliance

- Severe hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia unawareness:

° Major risk factors for pregnant women with Type 1 diabetes, particularly in the first trimester

° Aggravation by nausea, vomiting, and/or autonomic neuropathy.

Postnatal care

The aims for postnatal care are to:

- Have a written plan of management for blood glucose control and neonatal care. Ideally this should be decided 1–4 weeks prior to delivery, with the understanding that plans often change depending on clinical circumstances

- Encourage skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding within an hour of birth

- Enable all babies to remain with their mothers unless there are neonatal complications

- Encourage early feeding after delivery with monitoring of neonatal blood glucose if clinically indicated (chapter 22)

- Maintain acceptable maternal blood glucose control to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia:

° Target 4–7 mmol/L (72–126 mg/dL) premeals as nonpregnant goal. Avoid prebreakfast values less than 5 mmol/L (< 90 mg/dL) for 4–6 weeks

° Close monitoring of blood glucose if breastfeeding

- Discuss and provide (e.g. for oral or injectable) contraception and arrange for contraception (e.g. intrauterine contraceptive device [IUCD] insertion) at 5–6 weeks postpartum

- Arrange a 6-week follow-up clinic visit

- Offer women with GDM:

° A 6-week 75-g OGTT

° Advice on weight management, diet, and exercise

° An annual screening test for diabetes by their primary care physician

° Glucose testing prior to discontinuation of contraception when future pregnancy is desired.

ORGANIZATION: MEMBERS OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

The composition of the clinical team will vary according to local circumstances. Essential members of the team include an obstetrician and a diabetes physician supported by a diabetes specialist midwife, a diabetes specialist nurse, and a dedicated dietician. In US centers, other members may include a perinatologist and social worker. On the basis of clinical experience, we suggest that important characteristics of a multidisciplinary team should include that:

- It is comprised of motivated individuals with good interpersonal skills, and ideally possessing training in interview techniques and behavior change counseling

- The team members should meet regularly to discuss organization of the service, protocols, national standards, adverse events, audit, research and education.

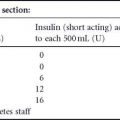

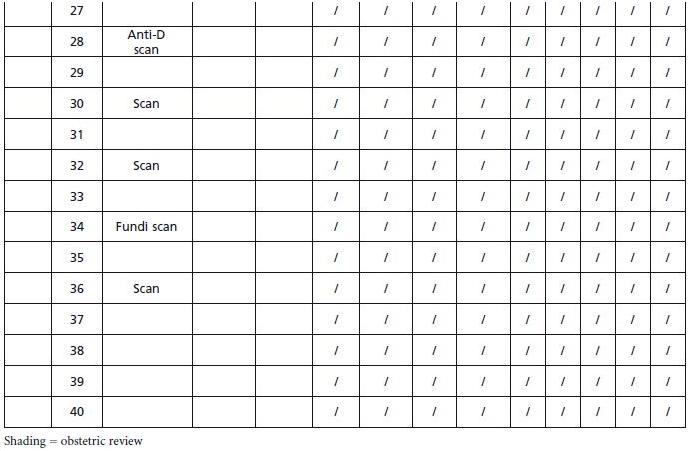

The organization of clinics will vary according to local circumstances. In our practice, we have eight clinic rooms to enable individual (one-to-one) consultations, and team members utilize a “high-tech” colored peg system outside each room to indicate which staff are required to see patients that week. This is determined by the week of gestation and the previous visit assessment (Fig 9.1. At the end of each clinic the investigations required at the next clinic visit are agreed upon, thus reducing phlebotomy and scanning waiting time.

The diabetes specialist midwife and diabetes specialist nurse provide telephone support, sometimes on a daily basis, to optimize glycemic control. The obstetricians and physicians have an on-call system providing continuous cover for emergency.

Roles of the multidisciplinary team members

Team members have some specific roles and some shared and/or exchangeable roles. Good communication between team members, including regular team meetings, and having clearly defined team goals facilitate task sharing. The role of each team member as developed from our own clinical experience is summarized in Tab 9.1.

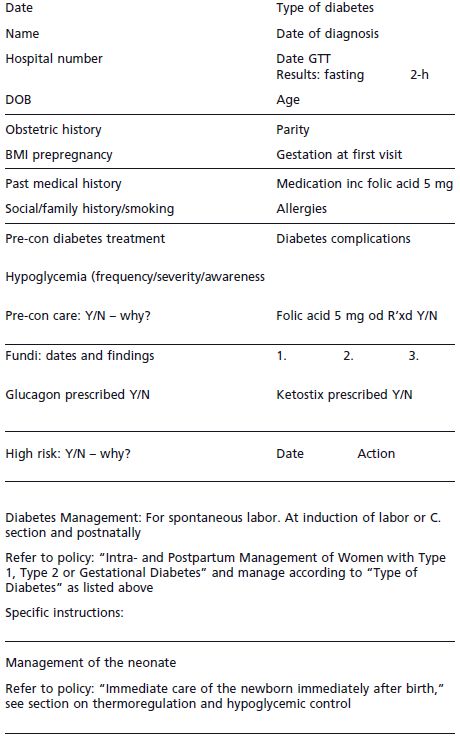

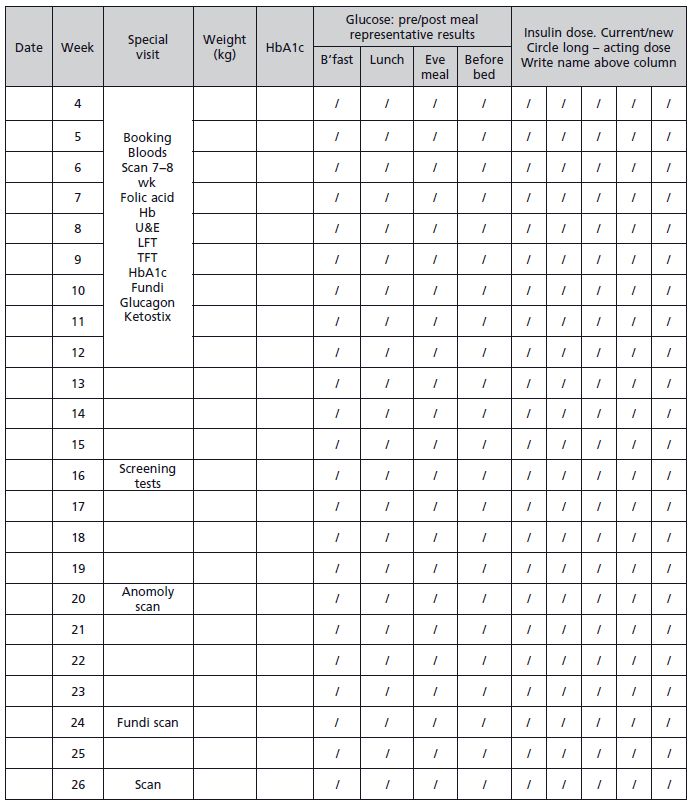

Figure 9.1 Diabetes in pregnancy proforma.

STANDARDIZATION OF SCHEDULES AND DOCUMENTATION

National guidance is particularly useful when quality of care is variable and the standard is often suboptimal.2 Here we describe our local practice which is broadly in line with the recommendations of the UK CEMACH guidelines.2

Preconception care tools

These will depend on the specific needs of the population served and local resources. The majority of our patients come from a multiethnic inner city population. With the help of our colleagues in primary care and the local hospital Diabetes Centre we have made, or are in the process of making, the following changes with the aim of improving preconception care:

- Recruitment of an Urdu-speaking diabetes specialist nurse to:

° Supervise the management of all patients referred for preconception care

° Develop links with the local ethnic communities and improve the acceptance and uptake of Western medical care

° Coordinate preconception services between primary and secondary care

- Creation of an educational poster to be displayed in all diabetes clinics in primary and secondary care

- Production of an educational DVD to be sent to all women with diabetes with child-bearing potential. This was developed with the participation of women who use our service

- Production of an educational leaflet to be mailed annually to all women with diabetes with child-bearing potential

- Sending annual educational text messaging and e-mail reminders to all women with diabetes with child-bearing potential.

Table 9.1 Roles of multidisciplinary team members.

| Team member | Roles |

| Team leader | • Chair monthly team meetings |

| • Liaise with primary care physicians | |

| • Coordinate regional policies and procedures |