Fig. 29.1

Multiple factors contribute to cancer-related morbidity The risks of late effects may be modified, either positively or negatively, by host (gender, age, race, genetics), cancer (location, histology, biology), or treatment (type, intensity) factors as well as behavioral practices. Practicing healthy lifestyles is the primary method survivors of adolescent and young adult cancers can use to reduce the risk of future health complications (Adapted with permission from Hudson [13])

29.2 Healthcare of Cancer Survivors

From the perspective of health and chronic disease models, cancer survivors represent an interesting population with health needs and healthcare utilization patterns that vacillate between a wellness and an illness model (Fig. 29.2). Prior to the symptomatic onset of the cancer, most individuals are “healthy” and operate in a wellness model, with preventive healthcare needs that are usually addressed by a primary care physician (PCP). With the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of cancer, the individual then assumes the role of “cancer patient” and is treated for the disease, generally in a chronic-care model with care focusing on the disease and provision of care provided largely by the oncology team. Upon completion of therapy and some interval thereafter, depending on the cancer, the patient is declared “cured.” Some survivors develop a chronic health problem as an early consequence of the cancer or cancer therapy. For instance, a seizure disorder may result from the location of a brain tumor or the curative surgery or radiotherapy. Such a survivor may continue in a chronic disease model and be monitored by a neurologist. As another example, an adolescent with an osteosarcoma may require limb-sparing surgery involving a lower extremity. The musculoskeletal system is permanently altered by the tumor and its treatment and long-term monitoring by an orthopedic surgeon would be anticipated. In both of these examples, the survivor would be cared for in a chronic disease model but would also have preventive care needs to be addressed.

Fig. 29.2

Health needs and healthcare utilization of survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer vacillate between a wellness and an illness model. Prior to the symptomatic onset of the cancer, most individuals are “healthy” and operate in a wellness model, with preventive healthcare needs that are usually addressed by a primary care physician With the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of cancer, the individual then assumes the role of “cancer patient” and is treated for the disease, generally in a chronic-care model with care focusing on the disease and provision of care provided largely by the oncology team. Upon completion of therapy and some interval thereafter, depending on the cancer, the patient is declared “cured.” Some survivors who develop a chronic health problem as an early consequence of the cancer or cancer therapy remain in a chronic-care model

Most AYA survivors, however, do not have a chronic health problem upon completion of their cancer therapy and thus, in a sense, enter back into the wellness model. Importantly, though, they have new long-term health risks, many of which have not been well characterized. Most survivors are not cognizant of their long-term health risks associated with the cancer therapy. Mentally and emotionally, many if not most survivors of AYA cancers figuratively close the door on the cancer chapter of their life. Similarly, most clinicians that provide care for a survivor outside of a cancer center setting are not familiar with the health risks of this relatively small and heterogeneous population. Operating in this mode, most clinicians will note the previous history of the cancer in the medical record, but will usually not consider the survivor as a high-risk individual and will rarely order screening or surveillance studies different than would be warranted in the general population.

Due to enhanced understanding of cancer treatment-related effects and risk adaptation of contemporary protocols, a sizeable proportion of survivors will have relatively minimal risk for clinically significant late effects [14]. For them, receiving healthcare that does not address their previous cancer likely will make little difference in their lives. Most, though, can be stratified into either middle- or high-risk groups. In the traditional wellness model, in which preventive care is delivered to the general population, a similar stratification of risk is incorporated. Most screening recommendations are based on genetic predispositions, comorbid health conditions, or lifestyle behaviors.

29.2.1 Risk-Based Healthcare of Survivors

Faced with these risks and challenges, how can the healthcare delivered to survivors be optimized? It is important to recognize that there is a window of opportunity to modify the severity of health outcomes by prevention or early intervention. Early diagnosis and intervention or preventive care targeted at reducing risk for late effects can benefit the health and quality of life of survivors [15, 16]. The outcomes of the following late effects can be influenced by early diagnosis and early intervention: second malignant neoplasms following radiation therapy (breast, thyroid, and skin), altered bone metabolism and osteopenia, obesity-related health problems (dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease), liver failure secondary to chronic hepatitis C following blood transfusion, and endocrine dysfunction following chest/mantle or cranial radiotherapy. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, including tobacco avoidance/cessation, physical activity, low-fat diet, and adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, can modify risk. Longitudinal care addressing other late effects, such as infertility, musculoskeletal problems, cognitive dysfunction, and psychosocial issues, may also improve survivors’ health outcomes and quality of life.

Based on these precepts, the concept of risk-based healthcare of survivors has evolved over the years. The term “risk-based healthcare,” coined by Meadows, Oeffinger, and Hudson, refers to a conceptualization of lifelong healthcare that integrates the cancer and survivorship experience into the overall lifetime healthcare needs of the individual [15, 16]. We endorse the following basic tenets of risk-based care: (1) longitudinal care that is considered a continuum from cancer diagnosis to eventual death, regardless of age; (2) continuity of care consisting of a partnership between the survivor and a single healthcare provider who can coordinate necessary services; (3) comprehensive, anticipatory, proactive care that includes a systematic plan of prevention and surveillance—a multidisciplinary team approach with communication between the PCP, specialists of pediatric and adult medicine, and allied/ancillary service providers; (4) healthcare of the whole person, not a specific disease or organ system, that includes the individual’s family and his cultural and spiritual values; and (5) a sensitivity to the issues of the cancer experience, including expressed and unexpressed fears of the survivor and his or her family/spouse. A systematic plan for lifelong screening, surveillance, and prevention that incorporates risks based on the previous cancer, cancer therapy, genetic predispositions, lifestyle behaviors, and comorbid health conditions should be developed for all survivors. To achieve continuity of risk-based management over the lifespan for AYA survivors of childhood cancer, the need for effective transition of survivorship care from pediatric-centered to adult-focused settings is implied [17].

Delivery of risk-based care is a core component featured in long-term follow-up (LTFU) programs that have been organized in academic cancer centers and community oncology programs in the United States, Canada, Europe, Asia, and Australia [18, 19]. However, geographic and financial barriers as well as age limits may preclude many AYA cancer survivors’ access to these programs that provide screening for late effects, including subsequent neoplasms, education regarding risks, and promotion of healthy lifestyles. These operations are resource intense and generally a low clinical revenue generator because of the limited or lack of reimbursement for significant components of the care [20]. Even in cancer centers with a LTFU program, most survivors gradually disconnect from oncology care as they age or move away and become “lost to follow-up.” Apart from cancer centers, few healthcare professionals see more than a handful of survivors, each with different cancers, treatment exposures, and health risks. This has led to increasing numbers of survivors who are not being followed by a clinician familiar with their risks and a general lack of risk-based care. To assist the clinician, regardless of setting, who cares for survivors, the following two sections describe briefly the general care of symptomatic and asymptomatic survivors.

29.2.2 Asymptomatic Survivors

As noted above, depending upon risks, survivors may benefit from early intervention or prevention. To assist the clinician in caring for the asymptomatic survivor, several groups have developed health screening recommendations to facilitate risk-based care of AYA survivors and are currently working collaboratively in an international forum to harmonize recommendations [21]. These guidelines are a hybrid, based on evidence and consensus. There is abundant evidence linking cancer treatment exposures to late effects [2]; however, because of the relatively small size of the heterogeneous survivor population, there are no studies (nor will there be in the near future) that show a reduction in morbidity or mortality with screening. As with other high-risk populations that are relatively small, limiting the types of studies evaluating the risks and benefits of screening and surveillance, there are two options in assessing the evidence. The first option is to state that, based on these limitations, there are no high-quality studies, thus limiting the strength of recommendation. However, to do so belies the wealth of high-quality studies from standard-risk populations that are applicable. Evidence gathered from studies in standard-risk populations can be extrapolated and used in the scientific basis of guideline development for high-risk populations. As principles from standard-risk populations are applied to high-risk groups, the two primary differences are timing of initiation and frequency of screening. By virtue of a lack of studies capable of answering these two questions, decisions must be founded on the biology in question within the grounded framework of risk and benefits.

29.2.3 Symptomatic Survivors

Although many survivors will remain asymptomatic, some will experience symptoms that may or may not be related to their risks and their previous cancer therapies. Clinicians who are not familiar with the population and are faced with uncertainty will often diverge to the extremes in evaluating a new problem. When young adult survivors present with symptoms not typical of their age group, their symptoms may be dismissed as anxiety or similar conditions, or conversely they may be over tested. Following are three recurrent themes that we have heard through our experience. A survivor who was treated with mantle or chest radiation faces an increased risk of premature coronary artery disease [10, 22]. When a survivor of Hodgkin lymphoma presents as a young adult with chest pain, clinicians who are not cognizant of this risk often attribute the pain to anxiety or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Likewise, clinicians may not be aware of the substantial risk of breast cancer during young adulthood experienced by women treated with chest radiation for an AYA cancer to advise early initiation of breast cancer surveillance [23, 24]. Another example is the obstetrician who is not familiar with the risks of late-onset cardiomyopathy following exposure to anthracyclines [3]. In young women with compromised subclinical ventricular systolic function, the increased intravascular volume associated with pregnancy and the increase cardiac workload during labor and delivery may trigger overt congestive heart failure secondary to an underlying, unrecognized cardiomyopathy [25].

Two methods can help to remedy this situation: educating survivors regarding the potential late effects of therapy and communicating with other healthcare professionals about the risks and needs of this population. First, it is critically important that the cancer center team educate the survivor and his or her family regarding potential late effects and their presenting symptoms as this information provides an important foundation to promote advocacy for survivorship care and resources. To be effective, education about late effects should be provided over time, beginning during or soon after completion of therapy. A summary of the cancer and cancer therapy should be provided to all cancer survivors. As needed, this summary should be updated and supplemented by exposure-specific educational materials. An excellent source of such survivor-targeted materials can be found in the Health Links that are provided with the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers (COG Guidelines) available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org [26].

Communicating with other healthcare professionals is a time-intensive, but critically important endeavor. Regardless of whether a survivor is followed in a LTFU program, he or she will inevitably interface with other healthcare professionals away from the cancer center. Cancer centers should provide contact information and easy accessibility for questions from survivors or their other healthcare providers. Online portals providing secure, interactive, remote access to a patient’s electronic health records are associated with high levels of engagement in chronic disease [27] and in a recent Dutch study were shown to be of interest among cancer survivors and health professionals as a means for obtaining health information and managing care [28]. Assisting other healthcare professionals in the interpretation of a survivor’s presenting symptoms or problems can be life altering.

29.3 Transition of Care

AYA cancer patients are a population with poorer survival outcomes that are hypothesized to be related to impaired access to appropriate care, advanced disease at diagnosis, differences in cancer and host biology, insurance barriers, and lack of clinical trial participation [1]. Characteristic age-related issues in the AYA population include fertility and psychosocial concerns, long-term side effects from cancer treatment, risk of chronic disease and future neoplasms, and insurance/financial barriers [29, 30]. With almost 70,000 AYA cancer patients (15–39 years old) diagnosed each year, the numbers of long-term AYA cancer survivors in need of cancer-focused follow-up care in the primary and tertiary care settings will increase significantly in the coming years [31].

In addition to the abovementioned issues, there is also a general lack of overall care coordination, transition from pediatric to adult care, or on-therapy to off-therapy care for this at-risk population of cancer patients. These care disparities require improvements in AYA patient and survivor programming, transition services, and care coordination strategies. Care coordination and transition of care are challenging for all cancer patients, but even more so for AYA patients who face many years at risk for late effects of therapy [32, 33]. Outcome data on AYA cancer patients are still evolving, but what is known is that “risk-based” medical care is essential for all cancer survivors. This level of medical care—which includes both the patients’ and physicians’ (e.g., PCP, oncologist) understanding of the cancer, the types of treatment that took place, and potential or actual late effects—can be a particular challenge for some AYA survivors due to their own lack of knowledge regarding treatment exposures and late effects, as well as limitations of access to care including insurance coverage [1, 34–36]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has recommended risk-based care, which has become a benchmark for quality survivorship care [37]. However, at the same time, risk-based care is complex and may be challenging to implement especially in resource-restricted healthcare settings [15, 16].

AYA cancer patients and survivors have physical and emotional health issues of which medical practitioners need to be aware [38]. PCPs and advanced practice providers (advanced practice nurses and physician assistants) currently play an important role in cancer-survivor care. Their comfort and expertise with this growing population of patients will be even more important during the next decade due to aging population of survivors and the decreasing number of medical oncologists resulting from an aging workforce [39]. The AYA cancer-survivor population is a small proportion (approximately 4 %) of the overall number of cancer survivors in the United States [31]. Transitioning from oncology-focused care to long-term follow-up care delivered by healthcare professionals often outside a cancer center requires education of providers. Recognizing that provider education is essential, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and AYA partner organizations have developed “Focus Under Forty” educational programs for oncology professionals, fellows, nurses and nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and PCPs. These programs were designed to increase awareness and enhance the understanding of care issues and challenges associated with the AYA patient population. The programs are free of charge, offer continuing medical education credits, and are available online at http://university.asco.org/focus-under-forty [40]. Promotion and distribution of educational and clinical resources like “Focus Under Forty” and published guidelines pertinent to the AYA population are vital in efforts to bridge the follow-up and knowledge gaps in AYA cancer-survivor care [23, 38, 41–45].

Establishing transition practices is one challenge within AYA cancer, but patient attendance in follow-up care is also of great concern. This concern stems from several studies of long-term childhood cancer survivors that have examined this transition process and report low participation rates for AYA-aged survivors in survivor-focused care. Among 9,434 adult participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), mean age at interview 26.8 years (range 18–48 years), only 19.2 % reported having a follow-up evaluation at a cancer center in the preceding 2 years [46]. This is especially concerning because most survivorship programs are housed within a cancer center. In a follow-up CCSS investigation specifically evaluating receipt of risk-based care by adult survivors of childhood cancer (mean age 31.4 years), only 31.5 % of survivors endorsed receiving care that focused on their prior cancer and even fewer (17.8 %) reported survivor-focused care that included advice about risk reduction or discussion or ordering of screening tests [36]. The treating oncologists’ desire to continue to see long-term survivors may also adversely impact their access long-term follow-up programs and successful transition of care [1]. This may result from the strong relationship forged during treatment as well as lack of confidence in the ability of the new provider to provide ongoing care.

29.4 Models of Survivor Healthcare Delivery

In general, there are three basic models of healthcare transition available to the AYA cancer patient that will be reviewed in this section: continued care at the original cancer center, care that is transitioned from the cancer treatment center to a PCP, and a hybrid model in which care is transitioned to a PCP in the community but with ongoing support from the cancer center [47]. AYAs are treated in a wide variety of academic medical centers and community-based clinics. They are a highly mobile population, which poses significant challenges for maintaining coordination and continuity of care. Establishing long-term follow-up care for AYA survivors is important regardless of where they received their initial cancer treatment. AYA survivors have potential for decades more life to live. However, over time a significant number of long-term AYA cancer survivors will suffer from chronic, debilitating medical conditions as a result of their cancer and treatment [3–7, 9, 12, 48, 49]. Our current understanding of these adverse outcomes come from reports published by cohort studies tracking the health of AYA cancer patients followed into the fourth and fifth decades of life [50–53]. At present, national standards provide important recommendations and suggest resources for both general and AYA-specific cancer survivorship care. In the United States, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer now requires accredited programs to implement treatment summaries and survivorship care plans for a portion of the patients and eventually all cancer patients [54]. These standards aim to improve communication, quality, and coordination of care for survivors.

As cancer centers across the country attempt to meet these new standards, the ASCO has diligently developed online resources to help guide program development via the ASCO Cancer Survivorship Compendium (available at http://www.asco.org//practice-research/asco-8907ecancer-survivorship-compendium) [55]. These online resources include a list of eight long-term follow-up care models and acknowledge that many factors such as the patient population and available resources will dictate which model is most appropriate at any particular institution. Models differ most notably in terms of location and who is providing the survivorship care and are categorized as (1) oncology specialist care, (2) multidisciplinary survivorship clinic, (3) disease-/treatment-specific survivor clinic, (4) general survivorship clinic, (5) consultative survivorship clinic, (6) integrated survivorship clinic, (7) community generalist model, and (8) shared care of survivor [55]. The ASCO Cancer Survivorship Compendium lists characteristics and limitations of each model which is provided for optimizing the success of the model chosen [55].

The model best suited for an individual AYA survivor will depend on variables such as the availability of resources and risk stratification (e.g., actual and potential late effects from therapy; risk for cancer recurrence or second malignant neoplasms) [15, 56]. In general, a few proposed models of care include a cancer center follow-up by the primary treatment team in a specialized long-term follow-up clinic or a primary care follow-up by the patient’s PCP, or most commonly it may be a combination of both types of providers [32].

In the first model, cancer center follow-up, an oncology team, or a specialized survivorship clinic within an oncology setting takes the lead in survivorship care [32, 47]. This broad model encompasses several models from the ASCO Cancer Survivorship Compendium’s list [55]. Examples range from follow-up visits with the primary oncologist to specialty survivor clinics that are specific to disease (e.g., breast cancer) or specific to AYA survivors. A growing number of academic medical institutions are developing multidisciplinary, LTFU survivorship programs. Each program is unique in their care delivery mode and some of the leaders for these programs include nurses and pediatric oncologists who have experience building survivorship programs [56]. If available, this type of model would be a good option for those survivors with the highest risk for adverse long-term outcomes including those treated with combined modality therapy for Hodgkin lymphoma or central nervous system tumors or those treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation [32, 57].

A second survivorship model is follow-up care that occurs within the scope of primary care and is provided by the patient’s PCP, e.g., nurse practitioner or family practice physician. A study regarding cancer survivorship practices for adult survivors of childhood cancer reporting from 179 Children’s Oncology Group institutions showed that 21 % of participating institutions utilize a “Community Referral Model” in which survivors are transitioned at adulthood to their PCP for routine cancer-related care. Care is managed and coordinated by the PCP, with the survivorship team/oncology team serving as consultants to multiple PCPs [18]. In general, this model may be a better choice for survivors assessed to be at lower risk for late treatment effects [15, 32]. The disadvantages of this model include some providers’ low comfort level with independently providing survivorship care and assuring that the appropriate and up-to-date knowledge about late effects and survivorship is maintained over time [58].

A third model, sometimes referred to as a hybrid model or “shared-care” model, involves the patient’s need for regular engagement with a team of providers, both oncologist and PCP. The shared-care model refers to care of a patient that is shared by two or more clinicians of different specialties. The basis of this model of care is periodic and ongoing communication between the specialist (e.g., oncologist) and PCP. The shared-care model has demonstrated improved patient outcomes in patients with chronic illness such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic renal disease [59–61]. When patients are on therapy or recently off therapy, they will have close contact with their team of oncology providers. However, when patients have completed therapy and the frequency of follow-up visits lapses, patients can become “lost in transition” and lose contact with their providers [37]. Therefore, a cancer survivorship model that includes care from both an oncologist and a PCP along the cancer trajectory can reduce the potential for patients becoming lost in transition. One potential disadvantage of this model is the extensive resources necessary to establish and maintain this model. Barriers of this model include the PCP’s lack of knowledge of various cancer drugs’ action, adverse effects, and long-term complications and the oncologist’s preference and internal medicine expertise in managing the patient’s comorbid conditions [56]. Overcoming these and other barriers with the shared-care model needs further investigation and attention from both primary and subspecialty providers. However, the feasibility of this model has been tested successfully in a pilot study of adult survivors of childhood cancers within the setting of a strong national health service [62]. A similar model promoting the PCP’s awareness of cancer survivorship-related issues through practice and education is a new role termed “the oncogeneralist” [63]. In this model of care, the PCPs have acquired deeper knowledge and familiarity with cancer survivorship through educational seminars, workshops, conferences, online programs, or shadowing in environments caring for cancer survivors [63, 64].

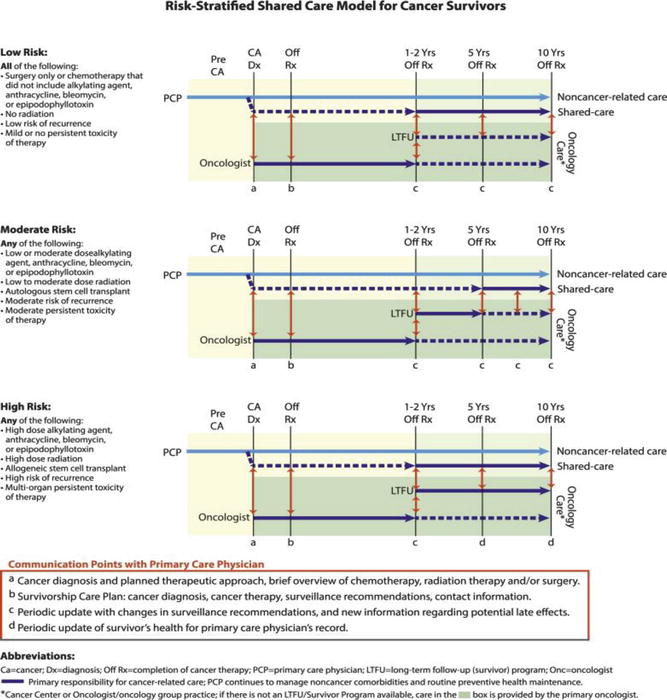

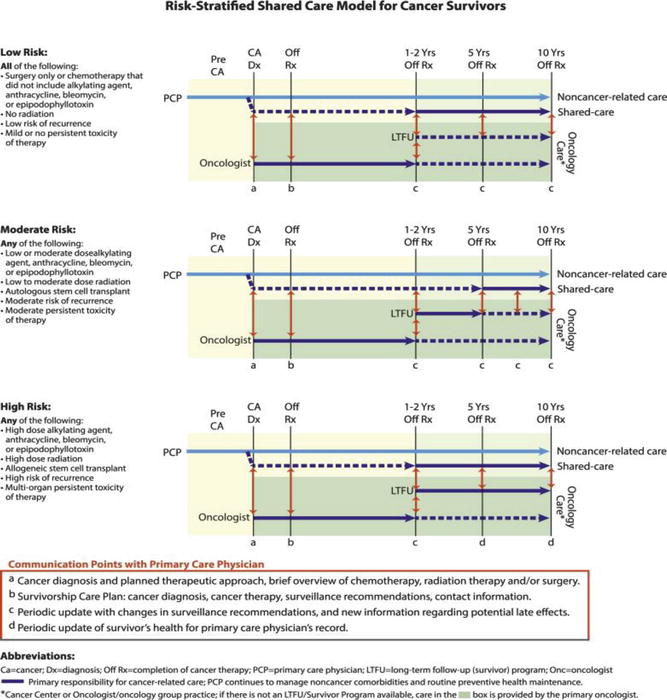

Another concept related to the shared-care model mentioned above is that of risk-stratified survivorship care [15]. The risk stratification assesses the questions of each survivor individually with focus on which type of provider should follow them, where the care should take place, the frequency, and screening modalities of follow-up. These stratifications will differentiate a survivor with mild or no toxicity from treatment, with low risk of recurrence, and with minimal risk of late effects from therapy. This is in contrast to a survivor who has established organ dysfunction, is at high risk for recurrence, or is at high risk for serious late effects from their cancer treatment [15]. Strategizing and planning for this type of risk-stratified survivorship care may be optimal in terms of patient outcomes, surveillance, and cost of care for patients and survivor programs alike. Figure 29.3 illustrates the Risk-Stratified Shared Care Model for Cancer Survivors.

Fig. 29.3

A risk-stratified shared-care model for cancer survivors assigns follow-up services based on intensity of therapy and risk of long-term and late effects. In the shared-care model, the roles and responsibilities of the oncology and primary care provider are defined to enhance coordination and reduce duplication of care (Reprinted with permission from McCabe [15])

Future studies are needed to assess the efficacy of various models of care specifically for AYA survivors. Ultimately, the goal of care for AYA cancer patients and survivors must be consistent with the specific needs of this population of patients. Salient survivorship issues to address include education and guidance with fertility, sexuality, contraception, self-management, interpersonal relationships, and psychosocial/emotional risk factors in addition to late effects screening and health maintenance. In addition, AYA care must provide guidance from providers on how to maintain effective access to insurance and healthcare services for the remainder of their lives [1, 17].

29.5 Promoting Healthy Lifestyles

29.5.1 Health Behavior Counseling of the AYA Cancer Survivor

Cancer and its treatment render AYA cancer survivors at greater risk for morbidity from health-risk behaviors than their peers without cancer [3, 11]. Chronic or subclinical changes persisting after treatment recovery may result in premature onset of common diseases associated with aging such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and second cancers [10]. In young people who are already at risk for many of these conditions, the addition of health-risking behaviors, such as smoking, poor nutrition, and inactivity, may increase this risk further [65–67]. Consequently, health professionals caring for AYA cancer survivors have the responsibility and challenge of motivating the practice of healthy lifestyles in this vulnerable group. Education about cancer-related health risks and risk-modifying measures for the adolescent and young adult cancer survivor can be readily integrated into routine follow-up evaluations. Health education in the oncology setting has several advantages. AYA cancer survivors have a close, long-term relationship with their oncology staff and generally respect them as credible medical experts. This relationship provides a strong foundation on which to introduce discussions about cancer-related health risks and risk-modifying behaviors. Survivors’ enhanced perceptions of vulnerability during the check-up may also create a “teachable moment” that facilitates reception of health promotion messages [68]. In particular, evaluations after completion of therapy in long-term survivors that focus on health surveillance, rather than disease eradication, provide an atmosphere favorable for health promotion discussions.

The optimal components of health promotion counseling of survivors described in detail by Tyc et al. are summarized in Table 29.1 [68]. To be truly informed about potential health risks, survivors need accurate information about their cancer diagnosis, treatment modalities, and cancer-related health risks. This is critical information that many survivors lack [35]. Health counseling should be personalized to consider the unique educational needs related to the individual survivor’s cancer experience. The content of traditional health programs can be modified to include information that enhances the survivor’s perception of increased vulnerability. Health behavior discussions should avoid characterizing the survivor as being different from healthy peers. An approach that starts first with a discussion of the adverse effects of health-risking behaviors followed by an explanation of the additional risks predisposed by cancer should reduce the survivor’s anxiety and permit identification with peers. The knowledge that certain behaviors are riskier for them than for others may provide some teens with a welcome excuse to resist peer pressure.

Table 29.1

Components of health promotion interventions with adolescent and young adult cancer patients

Inform of potential health risks |

Address increased vulnerability to health risks relative to healthy peers |

Provide personalized risk information relative to treatment history |

Establish priority health goals |

Discuss benefits of health protective behaviors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|