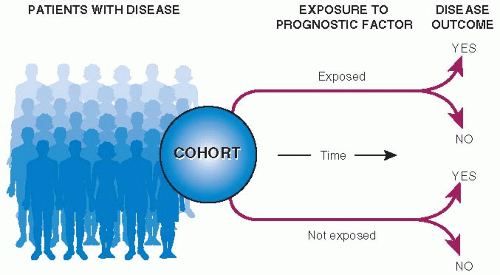

Figure 7.2 shows the basic design of a cohort study of prognosis. At best, studies of prognosis are of a defined clinical or geographic population, begin observation at a specified point in time in the course of disease, follow-up all patients for an adequate period of time, and measure clinically important outcomes.

Patient Sample

The purpose of representative sampling from a defined population is to assure that study results have the greatest possible generalizability. It is sometimes possible to study prognosis in a complete sample of patients with new-onset disease in large regions. In some countries, the existence of national medical records makes population-based studies of prognosis possible.

Even without national medical records, population-based studies are possible. In the United States, the Network of Organ Sharing collects data on all patients with transplants, and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program collects incidence and survival data on all patients with newonset cancers in several large areas of the country, comprising 28% of the U.S. population. For primary care questions, in the United States and elsewhere, individual practices in communities have banded together into “primary care research networks” to collect research data on their patients’ care.

Most studies of prognosis, especially for less common diseases, are of local patients. For these studies, it is especially important to provide the information that users can rely on to decide whether the results generalize to their own situation: patients’ characteristics (e.g., age, severity of disease, and comorbidity), the setting where they were found (e.g., primary care practices, community hospitals, or referral centers), and how they were sampled (e.g., complete, random,

or convenience sampling). Often, this information is sufficient to establish wide generalizability, for example, in studies of community acquired pneumonia or thrombophlebitis in a local hospital.

Zero Time

Cohorts in prognostic studies should begin from a common point in time in the course of disease, called zero time, such as at the time of the onset of symptoms, diagnosis, or the beginning of treatment. If observation begins at different points in the course of disease for the various patients in a cohort, the description of their prognosis will lack precision, and the timing of recovery, recurrence, death, and other outcome events will be difficult to interpret or will be misleading. The term inception cohort is used to describe a group of patients that is assembled at the onset (inception) of their disease.

Prognosis of cancer is often described separately according to patients’ clinical stage (extent of spread) at the beginning of follow-up. If it is, a systematic change in how stage at zero time is established can result in a different prognosis for each stage even if the course of disease is unchanged for each patient in the cohort. This has been shown to happen during staging of cancer—assessing the extent of disease, with higher stages corresponding to more advanced cancer, which is done for the purposes of prognosis and choice of treatment.

Stage migration occurs when a newer technology is able to detect the spread of cancer better than an older staging method. Patients who used to be classified in a lower stage are, with the newer technology, classified as being in a higher (more advanced) stage. Removal of patients with more advanced disease from lower stages results in an apparent improvement in prognosis for each stage, regardless of whether treatment is more effective or prognosis for these patients as a whole is better. Stage migration has been called the “Will Rogers phenomenon” after the humorist who said of the geographic migration in the United States during the economic depression of the 1930s, “When the Okies left Oklahoma and moved to California, they raised the average intelligence in both states” (

5).

Follow-Up

Patients must be followed for a long enough period of time for most of the clinically important outcome events to have occurred. Otherwise, the observed rate will understate the true one. The appropriate length of follow-up depends on the disease. For studies of surgical site infections, the follow-up period should last for a few weeks, and for studies of the onset of AIDS and its complications in patients with HIV infection, the follow-up period should last several years.

Outcomes of Disease

Descriptions of prognosis should include the full range of manifestations of disease that would be considered important to patients. This means not only death and disease but also pain, anguish, and the inability to care for one’s self or pursue usual activities. The 5 Ds—death, disease, discomfort, disability, and dissatisfaction—are a simple way to summarize important clinical outcomes (see

Table 1.2).

In their efforts to be “scientific,” physicians tend to value precise or technologically measured outcomes, sometimes at the expense of clinical relevance. As discussed in

Chapter 1, clinical effects that cannot be directly perceived by patients, such as radiologic reduction in tumor size, normalization of blood chemistries, improvement in ejection fraction, or change in serology, are not clinically useful ends in themselves. It is appropriate to substitute these biologic phenomena for clinical outcomes only when the two are known to be related to each other. Thus, in patients with pneumonia, short-term persistence of abnormalities on chest radiographs may not be alarming if the patient’s fever has subsided, energy has returned, and cough has diminished.

Ways to measure patient-centered outcomes are now used in clinical research.

Table 7.1 shows a simple measure of quality of life used in studies of cancer

treatment. There are also research measures for performance status, health-related quality of life, pain, and other aspects of patient well-being.