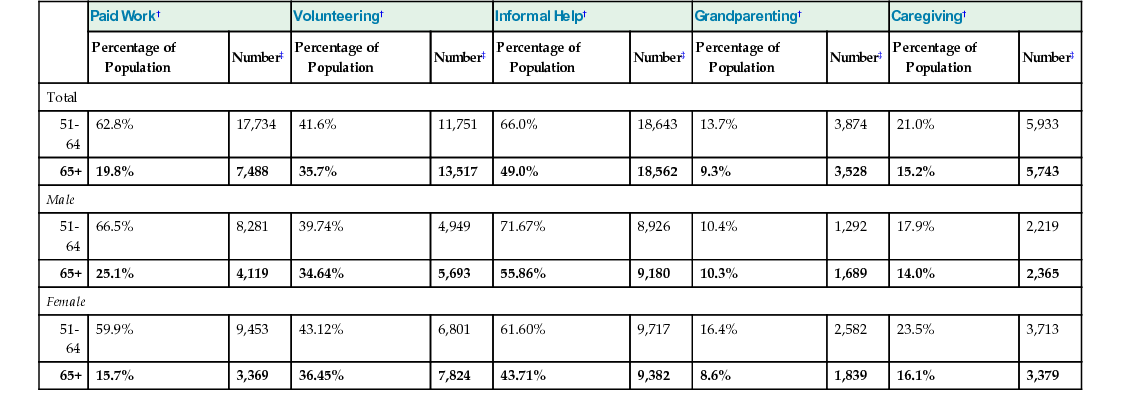

Jan E. Mutchler, Sae Hwang Han, Jeffrey A. Burr Far from being years of leisure and inactivity, later life is increasingly recognized as being characterized by high levels of productivity. The concept of productive aging captures both paid and unpaid activities that have social value and are performed by adults during the later years of the life course. Late life engagement in activities such as paid work, volunteering, informal helping, caregiving, and taking on the role of a grandparent caregiver are widely accepted as markers of productive aging. Estimates from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) suggest that well over half of U.S. adults age 65 and older engage in at least one of these productive activities, with participation in volunteering and informal helping being especially common. Productive aging has consequences for society as well as for the participant. The productive engagements of older adults are widely acknowledged to contribute substantially to society as a whole, and especially to the social groups, communities, and networks that directly benefit from the contributions. Older adults contribute millions of hours in unpaid productive activity, and many of these valued services would need to be paid for if they were not contributed by older adults. For example, Johnson and Schaner1 place a dollar value on these activities and estimate that in 2002, Americans age 55 and older generated $162 billion in unpaid activity through volunteering and caregiving alone. As well, participation in productive activities often directly benefits the older adult who participates in them. Some research finds participating in productive activities is linked to avoiding disease and even prolonging survival.2,3 In this respect, a clear pathway is evident between “productive aging” (participation in activities that have intrinsic value and contribute to the well-being of others) and “successful aging,” that is, aging with good health, high functioning, and active involvement.4 The focus of this chapter is on factors that shape engagement in productive activities in later life, referred to here as antecedents of productive aging, and on the consequences of productive aging. In considering antecedents, we review both individual-level factors that promote or inhibit participation and societal and cultural factors that shape the opportunities for older adults to participate. In addition, in reviewing consequences of productive activity, we offer a brief summary of the societal-level consequences, and we focus especially on the scientific literature suggesting that participation in productive activities contributes to health and well-being in later life. Previous editions of this volume included a chapter on productive aging authored by Robert N. Butler, MD, widely regarded as the founder of the concept. Butler traced the creation of the concept of productive aging to the recognition that older adults had much to contribute well into later life, yet they encountered societal barriers to participation in the form of ageism and prejudice. Indeed, early in the development of this concept, Butler5 suggested that ageism should be treated as a disease, with productive aging pursued as a remedy. Butler’s insights, and his advocacy on behalf of older adults, established a framework for re-envisioning later life and promoting activity as a means of preserving health and well-being. The following discussion highlights the enduring usefulness of these insights. The research literature on productive aging places emphasis on five forms of productive activities frequently performed by older adults: paid work, volunteering, caregiving, informal helping, and grandparenting. In this section, we describe these activities and offer recent evidence on how participation in each is related to age and gender. The data used here to describe productive activity among middle-aged and older adults are taken from the 2010 version of the HRS. The HRS contains a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States age 51 and older. The HRS is one of only a handful of data files that contain national-level information on all five of these forms of productive activity. Other sources of information describing some of these specific activities are available, and the statistics generated from the HRS may not match those generated from these other sources, largely because of differences in research design. Readers should keep this in mind when comparing our numbers to those generated from other sources. The capacity of the older population to serve in the paid labor force was, and sometimes still is, considered as the standard indicator of productivity by some observers. Typical indicators of economic performance, such as the gross domestic product, omit estimated monetary values of voluntary activities and informal contributions made by older adults.6 Despite the distinctive age curve in labor force participation, which peaks during late middle age and declines thereafter,7 a considerable number of older workers remain in the labor force well into the later stages of the life course. We estimate that about 18 million adults ages 51 to 64, and 7.5 million age 65 and older, were working for pay in 2010 (see Table 32-1). Moreover, older adults are expected to comprise a larger share of the workforce in coming years. Estimates suggest that the share of the labor force composed of workers age 55 years and older will increase to 26% in 2022, up from 12% in 2012.8 As demonstrated with HRS data (Table 32-1), there is a considerable difference in labor force participation between older males and females, with males being more likely than females to be in the labor market in later life. However, recent data suggest a narrowing of the gender differences, as a result of declining participation among men and rising participation among women contributing to the trend. TABLE 32-1 Productive Activity Participation Rates by Age Group and Sex (Estimated from the 2010 Health and Retirement Study*) Older workers do not show much difference in the type of work they do and what they do when compared with their younger counterparts, as they can be found in most industries and occupations, broadly classified. However, older workers are more likely than younger workers to be self-employed or to work part-time.9 For some older adults, these forms of employment may be pursued as part of a phased retirement strategy, working fewer hours for the same employer, or working in a bridge job with a different employer, each serving as a stepping-stone from full-time work to full retirement. Volunteer work includes unpaid work performed through an organization with the intent of benefitting others. Volunteering can be distinguished from other forms of productive activities, such as informal helping or caregiving, not only by the context of a formal organizational structure within which the activity is performed but also with reference to those who receive the help. Typically, volunteers have no contractual, familial, or friendship relationships with the persons or groups who are helped.10 Historically, volunteer work has been regarded as an important form of productive activity in old age, as volunteering was one of the few formal roles available to older adults in their postretirement years.11 Similar to paid work, volunteering shows a distinct life-course pattern, where the rate of volunteering peaks during middle age and diminishes somewhat in later life.12 In 2010, about 36% of respondents in the HRS who were age 65 and older reported participating in formal volunteer activities, showing a slightly lower level of participation in this activity as compared with middle-aged adults (42%, see Table 32-1). Yet the number of hours committed per volunteer is higher among older volunteers as compared to middle-aged volunteers.12 Gender differences in rates of volunteer are minimal, as shown in Table 32-1. Although volunteering is defined as unpaid work provided through formal organizations, observers agree that focusing only on help provided in these contexts excludes important informal help provided by older adults.13 Accordingly, many scholars have acknowledged informal helping behavior as an alternative type of volunteerism that occurs out of public view and in support of neighbors, friends, and others who live outside of one’s own household.13,14 Informal helping is relatively understudied compared to other forms of productive activities. Evidence from the HRS shows that a substantial fraction of the population of middle-aged and older adults are engaged in informal helping (66% and 49%, respectively), with informal helping surpassing formal volunteering in number of participants (see Table 32-1).15 The term grandparenting encompasses a wide range of care-providing activities. These include occasional babysitting for grandchildren, taking on supplemental or co-parenting responsibilities in multigenerational households, and taking primary responsibility for raising one or more grandchildren.16 Recent reports indicate that a growing number of older adults may be involved in grandparenting in a co-parenting situation: in 2011, about 7 million grandparents were co-residing with their grandchildren, which marks a 22% increase from 2000. More than 2.7 million grandparents are also found to be the primary caregiver for a grandchild.17 Moreover, a substantial portion of older adults are also engaged in occasional grandparenting. As shown in Table 32-1, approximately 7 million grandparents age 51 and older are providing more than occasional grandchild care (e.g., at least 50 hours annually). Although the research literature makes clear that grandmothers are more likely than grandfathers to serve as substitute parents for their grandchildren, data from the HRS (see Table 32-1) suggest that men age 65 and older may be involved in at least some forms of grandparenting at a greater rate than women. Caregiving is another form of intrafamily productive activity that is gaining more attention in light of the growing need for informal, unpaid care work. A sizable portion of the adult population provides care to a parent, spouse, sibling, or adult child who is ill or disabled. Approximately 21% of middle-aged and 15% of older adult respondents report providing care for another adult at least once a month (see Table 32-1). Women are somewhat more likely than men to participate in caregiving. In caregiving, as with other forms of productive activity, gender comparisons are highly sensitive to measures used, with the result that different studies report different levels of gender disparity. A recent study suggests that what sets older caregivers apart from their younger counterparts is their level of involvement in caregiving: caregivers aged 65 and older provided 31 hours in an average week of caregiving, whereas those in the younger age group provided 17 hours. As well, older (65 years and older) and middle-aged (age 50 to 64) caregivers occupy the caregiving role for a longer period of time (7.2 and 4.9 years, respectively) compared to caregivers aged 49 and younger (3.7 years). The care recipient’s relationship to the caregiver is also age-graded. Whereas caregivers 65 and older are more likely than younger caregivers to care for a spouse or a sibling, younger caregivers are more likely than older caregivers to care for family members of an older generation, such as their parent or parent-in-law.18

Productive Aging

Introduction

A Portrait of Productive Aging in the United States

Paid Work

Paid Work†

Volunteering†

Informal Help†

Grandparenting†

Caregiving†

Percentage of Population

Number‡

Percentage of Population

Number‡

Percentage of Population

Number‡

Percentage of Population

Number‡

Percentage of Population

Number‡

Total

51-64

62.8%

17,734

41.6%

11,751

66.0%

18,643

13.7%

3,874

21.0%

5,933

65+

19.8%

7,488

35.7%

13,517

49.0%

18,562

9.3%

3,528

15.2%

5,743

Male

51-64

66.5%

8,281

39.74%

4,949

71.67%

8,926

10.4%

1,292

17.9%

2,219

65+

25.1%

4,119

34.64%

5,693

55.86%

9,180

10.3%

1,689

14.0%

2,365

Female

51-64

59.9%

9,453

43.12%

6,801

61.60%

9,717

16.4%

2,582

23.5%

3,713

65+

15.7%

3,369

36.45%

7,824

43.71%

9,382

8.6%

1,839

16.1%

3,379

Volunteering

Informal Helping

Grandparenting

Caregiving

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Productive Aging

32