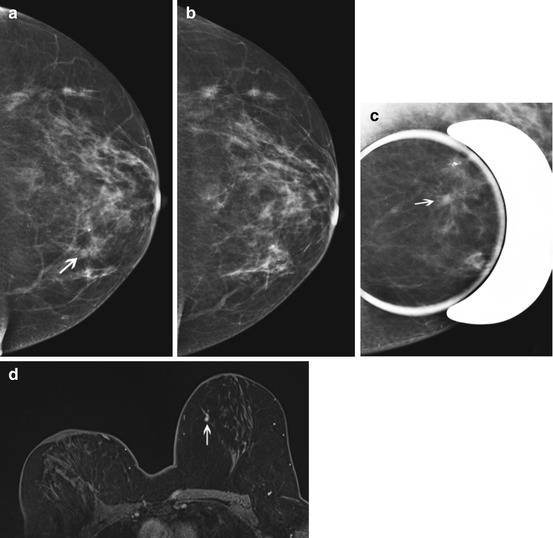

Fig. 7.1

Sixty-four year old with a screen recalled asymmetry (arrow) in the medial right breast on the CC view (a), persistent (arrow) on spot compression CC (b), but not evident on ML view (c). Rolled CC views show a pliable appearing asymmetry (arrow) on the medially rolled CC view (d), but no abnormality on the laterally rolled CC view (e). The equivocal asymmetry was localized to the upper inner breast (based on its displacement on the medially rolled CC view relative to the full CC view) for diagnostic US evaluation, which was negative. The patient was referred for problem solving MRI. Axial post contrast fat suppressed image (f) shows a 5 mm enhancing mass (arrow), which represented a stage 1, 0.7 cm invasive ductal cancer

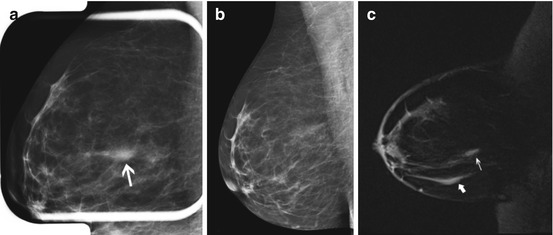

Fig. 7.2

Forty-eight year old recalled for developing focal asymmetry in the right upper outer breast on screening views (not shown). The finding persisted on spot compression MLO view (a, arrow) and ML view (not shown), and was new since the prior MLO view (b). Targeted ultrasound was negative. The patient had undergone a twenty pound weight loss since the prior imaging and it was uncertain if the developing asymmetry was due to differences in tissue composition and mammographic compression versus a true lesion. MRI was performed, and sagittal post contrast fat suppressed image (c) showed normally enhancing fibroglandular tissue (thin arrow), which appeared similar to other areas of normally enhancing fibroglandular tissue (thick arrow). The patient underwent mammographic surveillance, and has been without evidence of disease for greater than 3 years

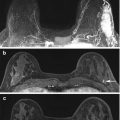

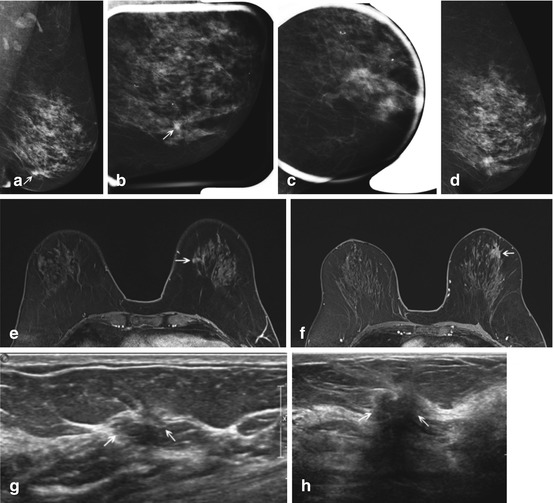

Fig. 7.3

Fifty-five year old with prior right lumpectomy and questionable subtle asymmetry (arrow) in the medial left breast on the CC view (a) only, apparently new since the prior CC view (b). Biopsy clip lateral to the finding was from a prior benign biopsy. The one view finding was subtle and equivocal on spot compression CC view (c, arrow), and felt to be difficult to identify in a background of heterogeneously dense tissue for an attempted stereotactic biopsy. US evaluation of the medial left breast was negative. Problem solving MRI was performed for further evaluation. Axial fat suppressed post contrast image (d) showed a correlative 4 mm enhancing mass in the medial left breast, which represented an invasive lobular cancer, stage 2

A number of studies have evaluated the use of MRI for problem solving of equivocal mammographic lesions [21, 23–25]. In 1998, Sardanelli et al. [23] published results on 19 mammographic findings considered equivocal that underwent diagnostic MRI. Lesions included questionable change in the appearance of lumpectomy scar (N = 11), questionable distortions (N = 2), “nodular opacities” (N = 5), or calcifications (N = 1). There were five (26.3 %) malignancies, one with negative MRI. The following year, Lee et al. [24] described the use of problem solving MRI for 86 equivocal mammographic findings in their institution. These 86 lesions included lesions that demonstrated questionable/uncertain change (N = 26), questioned lesions that could not be localized (N = 16) or persisted on only some views (N = 20), or questioned change in the appearance of a benign surgical site (N = 9) or lumpectomy scar (N = 15). They had 9 (10.5 %) malignancies, and one additional malignant lesion incidentally detected by MRI. Moy and colleagues [21] had 115 equivocal mammographic lesions referred for problem solving MRI, including asymmetries (N = 55), focal asymmetries (N = 43), architectural distortions (N = 12), and change in appearance of a benign surgical scar (N = 5), with 6 (5.2 %) malignancies. Spick et al. [25] reported 111 patients with inconclusive findings on conventional mammographic or ultrasound imaging assessed as BI-RADS 0 who underwent problem solving MRI, with 15 (13.5 %) malignancies. At our institution (unpublished data) over a 4 year period, we had 294 equivocal mammographic lesions (including 89 focal asymmetries, 76 asymmetries, 64 masses, 44 architectural distortions, 17 scars versus malignancy, and 4 miscellaneous) referred for problem solving MRI, with 40 (13.6 %) malignancies (Fig. 7.4). Other studies [15, 26] did not specify lesion types considered equivocal, and reported equivocal clinical and imaging findings together, making direct comparison of their results to the aforementioned studies challenging.

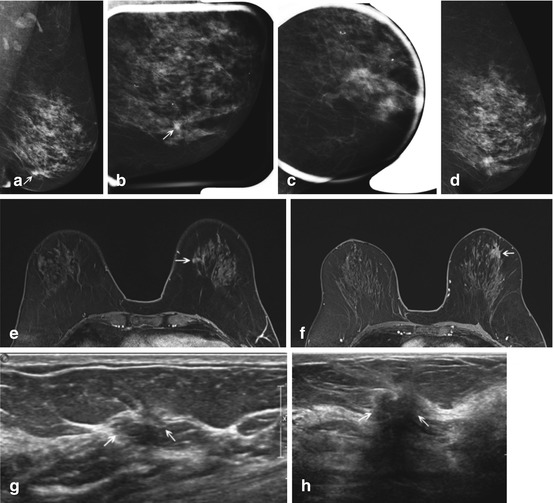

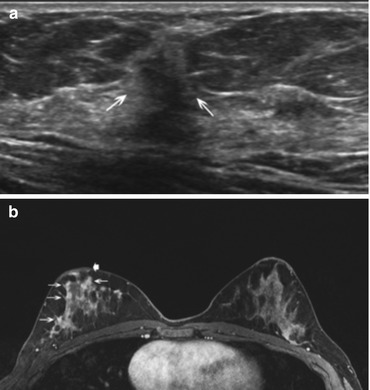

Fig. 7.4

Sixty-eight year old with a one view asymmetry (arrow) with questionable associated distortion on screening left MLO view (a). The finding persisted on one spot MLO view (b) but was not persistent on another spot MLO view (c), nor on an LM view (d), which both showed heterogeneously dense tissue but no discrete finding. The questioned finding was not seen on the CC view (not shown) and targeted US evaluation was negative. The finding was considered equivocal, and problem solving MRI was performed. Axial fat suppressed post contrast enhanced images (e, f) showed an area of non-mass enhancement (arrow, e) in the left lower inner quadrant corresponding to the mammographic equivocal asymmetry, as well as an incidentally detected, mammographically occult spiculated mass in the upper outer quadrant (arrow, f). Both findings demonstrated slow early and persistent late kinetics. Repeat targeted ultrasound (g, h) showed a subtle area of architectural distortion (g, arrows) corresponding to the mammographic asymmetry, and a hypoechoic ill-defined mass with posterior acoustic shadowing (h, arrows) corresponding to the incidentally detected spiculated mass. Findings represented multi-centric invasive lobular cancer, stage 2, with positive sentinel node

The possibility of detecting otherwise unsuspected, incidental findings in patients undergoing MRI is not at all uncommon [27]. This is an important consideration, since otherwise unsuspected but ultimately benign findings detected solely on MRI generate additional costs with either biopsy or follow up imaging surveillance. An otherwise unsuspected occult malignancy detected by MRI is even less common. However, only a few of the studies on the use of MRI for equivocal mammographic lesions reported their incidental MRI findings [21, 24]. Lee et al. [24] found 12 incidental enhancing lesions on MRI, with one (8.3 %) malignancy. Moy et al. [21] had 18 incidental enhancing lesions on MRI, all benign on either follow up or biopsy. At our institution (unpublished data), out of 294 problem solving MRIs over a 4 year period, we had 44 incidental enhancing lesions, 41 had biopsy or at least 1 year of stable follow up imaging, and 7 (17.0 %) were malignant (Fig. 7.4).

7.2.4 Recurrence Versus Scarring After Breast Conservation Therapy

A type of equivocal situation on mammography which deserves individual discussion is that of breast cancer recurrence versus post treatment change after breast conservation therapy. This was an early utilization of breast MRI for problem solving, because it is well known that mammography has reduced sensitivity for malignancy after breast conservation therapy [28]. Sometimes it may be unclear whether an apparent mammographic change in the lumpectomy scar’s appearance (such as increased density) is due to technical factors or a subtle recurrence.

Several studies have reported that MRI was able to distinguish recurrent breast cancer from scar [29–33]. Heywang et al. [29] found that the performance of MRI less than 18 months following definitive surgery was unhelpful due to post-surgical enhancement, but that after 18 months treatment related enhancement was rare. They concluded that after 18 months MRI allowed both early detection of, and reliable exclusion of recurrent tumor. In 1998 Viehweg et al. [30] performed MRI in 207 women with a history of breast conservation therapy, 80 of whom had suspicious clinical or conventional imaging findings. Similarly to Heywang et al. [29], they found that MRI performed within 12 months of definitive surgery was of limited value because of enhancement due to benign post-treatment changes, but that after 12 months MRI had a sensitivity of 100 % and a specificity of 91 % in the detection of recurrent tumor. Gilles et al. [31] performed MRI in 26 patients with suspected recurrence based on clinical or mammographic findings, and found that all 14 surgically proven recurrences demonstrated enhancement on MRI, while 11 of 12 without recurrence showed no enhancement. There was one false positive MRI due to fat necrosis. Preda and colleagues [32] performed breast MRI in 93 patients suspected of local recurrence after breast conservation based on mammographic and ultrasound findings. In their series, MRI had a 90 % sensitivity, 91.6 % specificity, 56.3 % positive predictive value, and 98.7 % negative predictive value for the detection of recurrence at the lumpectomy bed, and they suggested that MRI could be useful to avoid unnecessary biopsy. In a meta-analysis of studies using breast MRI to distinguish post treatment changes from recurrence [33], Quinn et al. found the sensitivity of MRI in detecting recurrence to range from 75 to 100 % with a specificity of 66.6 to 100 %, with both sensitivity and specificity improving with a longer interval between definitive surgery and MRI. The authors noted however, that the studies evaluated in the meta-analysis were case series with heterogeneous populations, and suggested that while MRI could be helpful as a second line investigative tool for possible recurrence, it should not be performed routinely in this setting.

7.3 Clinical Findings

7.3.1 Nipple Discharge

Nipple discharge is a relatively common symptom in women presenting for diagnostic imaging evaluation. In Leis’s series of 8,703 breast surgeries, nipple discharge was the presenting symptom in 7.4 % of cases [34]. Pathologically significant discharge is often described as unilateral, spontaneous, arising from a single duct, and bloody, clear or serous. Benign etiologies are the most common causes of nipple discharge. In one study reporting 586 patients who had surgery for clear (watery), serous (yellow), serosanguineous (pink), or bloody discharge, the majority had a benign etiology, including 48 % with intraductal papilloma, 33 % with fibrocystic changes, 14 % with cancer, and 7 % with precancerous lesions [34]. Patients with a bloody nipple discharge had a markedly higher breast cancer risk (404 of 1632, OR 2.27), compared with patients with non-bloody nipple discharge (179 of 1478) in Chen’s meta-analysis [35].

In patients with a clinically concerning discharge, conventional imaging with mammography, ultrasound, and galactography may fail to identify an underlying lesion. Conventional galactography with cannulation of the discharging duct and injection of iodinated contrast is invasive and may be painful for the patient or unsuccessful. The gold standard in management of patients with a clinically suspicious nipple discharge and negative imaging findings has been surgical duct excision. Nipple discharge cytology has a high false positive rate; negative cytology with negative imaging has not been found to have a sufficiently high negative predictive value to avoid surgery in patients with a clinically suspicious discharge [36].

In patients with negative conventional imaging, MRI may have potential to identify both malignant and benign lesions. In one study of 15 patients who underwent excisional biopsy for nipple discharge, MRI findings correlated with histology in eleven patients [37]. MRI correctly identified four of six papillomas and one of two fibroadenomas as circumscribed masses and six of seven malignancies as peripherally enhancing irregular masses or regional or ductal enhancement. In a different retrospective study of 55 patients with bloody nipple discharge, MRI demonstrated all malignancies [38].

MRI shows superior performance in the evaluation of nipple discharge compared to ductography [39]. Morrogh et al. [39] retrospectively reviewed 306 patients with nipple discharge and negative standard imaging evaluation, 186 patients who underwent ductography (N = 163), MRI (N = 52) or both (N = 29) before surgery. They found a higher predictive value for malignancy for MRI compared with ductography. They reported that MRI had a positive predictive value of 56 % and a negative predictive value of 87 %. Nakahara et al. [38] found that MRI most clearly demonstrated the location and distribution of lesions, especially DCIS, compared with galactography and sonography, in 55 patients with bloody nipple discharge. MRI demonstrates extent of disease better than the other modalities (Fig. 7.5) [38].

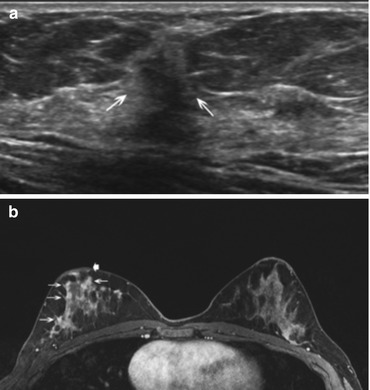

Fig. 7.5

Forty-three year old woman with 3 weeks of bloody nipple discharge, possible nipple retraction, and retraction of the breast. Mammogram (not shown) from an outside institution showed dense breast tissue but was negative. Ultrasound (a) of a focal area of concern in the right breast at 10:00 demonstrated a 6 mm hypoechoic mass (arrows) with irregular margins and posterior shadowing. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy was performed with pathology of invasive ductal carcinoma, grade II, ER/PR positive, Her-2 neu negative. Because the mammographic and sonographic imaging underestimated the clinical extent of disease, breast MRI was performed. Axial fat suppressed post contrast MRI (b) shows extensive diffuse clumped non mass enhancement (arrows) throughout the right breast with persistent kinetics and mild nipple retraction (thick arrow). The patient was treated with preoperative chemotherapy followed by mastectomy and implant reconstruction. The mastectomy specimen showed residual invasive ductal carcinoma microscopically in all four quadrants and in 2/7 lymph nodes. The MRI was helpful in confirming clinically suspicious more extensive disease than demonstrated on conventional imaging

Investigators have attempted to find other methods for evaluating the ductal system in the setting of nipple discharge. Direct MR-galactography, T1 and T2-weighted sequences after injection of gadolinium into the discharging duct, was compared with indirect MR-galactography, a T2-weighted sequence, in 23 patients with pathologic discharge and pathologic conventional galactogram [40]. Indirect MR-galactography has the advantage of being non-invasive and does not require radiation or contrast. Eight of the 23 women showed additional findings at direct MR-galactography in comparison with standard imaging sequences, indicating that the non-invasive T2-weighted sequences were suboptimal.

One study compared direct MR-galactography and conventional galactography in 30 patients and found no significant difference, suggesting that there is no additional advantage to MRI after galactogram [41]. Direct MRI-galactogram has disadvantages such as additional cost and the need to schedule magnet time compared with conventional galactogram. Both techniques may show a lesion as an intraductal filling defect, irregular duct wall, or ductal obstruction. Neither technique may specifically differentiate benign from malignant pathologies. In addition, a failed study may result if the radiologist is unable to cannulate the discharging duct and introduce contrast, or if multiple ducts have discharge.

Several studies have shown that MRI has the highest sensitivity in detecting benign or malignant etiologies for nipple discharge compared with other imaging modalities Nicholson et al. [42] found that MRI had the highest sensitivity, PPV, and NPV compared with conventional galactogram or indirect MR-galactogram, a heavily T2-weighted sequence, in 21 patients. Lorenzon et al. [43] retrospectively compared the sensitivity of MRI, mammography and ultrasound in 38 patients with nipple discharge and found MRI had statistically significant higher overall sensitivity. They concluded that MRI should be recommended when conventional imaging is negative. Advantages to MRI are that it is non-invasive and can image the ducts, subareolar area adjacent to the ducts, remainder of the breast and contralateral breast, whereas galactogram images a single ductal system.

In 2011, Yau et al. [15] reviewed 204 MRIs at their institution that had a clinical indication of problem solving. One hundred twelve of these had a problem identified by clinical breast examination. Two cancers were detected in patients with suspicious nipple discharge, negative mammogram and ultrasound, and failed or negative ductography. One of these two patients had prior lumpectomy for DCIS, the other is not further detailed in the report. They found one incidental cancer and one false negative MRI. They reported that at their institution, the patients with the suspicious nipple discharge and negative conventional imaging would have undergone surgical duct excision regardless of the MRI findings. However, they suggested that the utility of MRI for suspicious nipple discharge needs to be further investigated.

Sanders et al. [44] compared outcomes of 200 patients who had central duct excision for bloody nipple discharge following negative conventional imaging, 115 without and 85 with preoperative MRI. In their retrospective review, of 115 patients without pre-operative MRI, duct excision showed 8 (7 %) malignancies, including 7 DCIS and one invasive ductal cancer. In the 85 patients with pre-operative MRI, there were 8 (9.4 %) malignancies, all DCIS, and 7 were detected at MRI (true positives). The one falsely negative MRI represented Paget’s disease on nipple biopsy. Fifty-six patients had a benign or negative MRI; central duct excision was negative for malignancy in all with the exception of the false negative MRI. The sensitivity and specificity were 88 and 71 %, and PPV and NPV were 24 and 98 %. Their conclusion was that the extremely high negative predictive value of MRI suggests that a negative study could obviate surgical duct excision in most patients, unless overriding clinical factors prevail.

In the surgical literature, Morrogh et al. [45] reported 416 cases of nipple discharge, 287 that underwent definitive biopsy or surgery, and 56 that had pre-operative MRI. Of 13 malignancies found in the group that had pre-operative MRI, 10 (77 %) had a suspicious MRI correlate. Unpublished review of diagnostic breast MRIs at our institution performed for nipple discharge over a 3 year period revealed 83 patients, 40 of whom underwent biopsy, yielding 6 malignancies, 16 papillomas, and 18 miscellaneous benign histologies. MRI was positive in 5 of 6 malignancies and 13 of 16 papillomas; the sensitivity of MRI for detecting papilloma or malignancy was 82 % and specificity was 67 % for biopsied cases.

In summary, in patients with negative conventional imaging and suspicious clinical nipple discharge, contrast-enhanced MRI has the highest sensitivity compared with other imaging modalities, including conventional galactogram, and indirect- and direct-MR galactography. It has been proposed that the high negative predictive value of MRI suggests that a negative study may obviate surgical duct excision in most patients, unless overriding clinical factors prevail [44]. Other authors have suggested that clinical stratification can reliably identify pathologic discharge [39, 45], and that since MRI did not identify all malignancies and was unable to distinguish benign from malignant etiologies for discharge, that surgical duct excision should remain the gold standard of care. Surgical duct excision serves both a diagnostic as well as a therapeutic role for bloody nipple discharge, and this should be balanced against the cost of breast MRI. However, further investigation is warranted regarding the utility of problem solving MRI in this subset of patients, because a standard imaging algorithm remains elusive.

7.4 Palpable Findings with Negative Mammogram and Ultrasound

In patients with a suspicious palpable clinical finding, a complete evaluation with diagnostic mammography and ultrasound is the initial imaging recommendation by the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommendations and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines [46, 47].

The majority of patients will either have a negative mammogram and ultrasound, with a sufficiently low clinical suspicion that clinical follow up is recommended rather than further advanced imaging, or a finding prompting biopsy on diagnostic mammography and/or ultrasound. A few will have a probably benign imaging finding for which short interval follow up imaging is recommended. Multiple studies have shown an extremely high negative predictive value of mammography and ultrasound in evaluation of patients with a palpable lump, ranging from 97.4 to 100 % [9–11, 48]. However, negative imaging should not preclude biopsy if there is a suspicious clinical finding.

The 2013 ACR Appropriateness Criteria for Palpable Breast Masses are evidence-based guidelines for specific clinical conditions developed by a multidisciplinary expert panel [46]. Diagnostic mammography is recommended in the initial evaluation in women age ≥40 with a palpable lump, followed by focal ultrasound targeted specifically to the palpable finding. The addition of ultrasound to diagnostic mammography has been shown to increase the true-positive rate [10, 49]. However, MRI is categorized as “usually not appropriate” as the initial imaging evaluation in women age ≥ 40 and women < age 30 with a palpable lump.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree