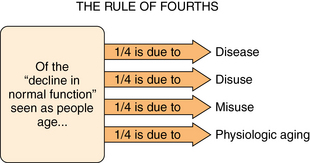

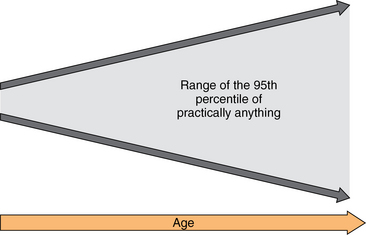

1 Looking Old but Not Feeling or Thinking Old Life Review and Adjustment to One’s Changing Life Status Cognitive Impairment and Worry Delivery of Primary Health Care to Older Persons Multiple Morbidity and the Geriatric Syndromes Function, Not Diagnosis, is What Counts The U.S. Health Care Nonsystem Transitions in Care are Dangerous Interprofessional Nature of Geriatric Care A Generalist is Often the Best Physician for a Geriatric Patient Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe and identify at least one clinical implication of each of the following key aspects of physiologic aging: the rule of fourths, normal physiologic changes, functional reserve, reduced stamina and fatigue, increased physiologic diversity, the relationship between environment and function, and immobility in older persons. • Describe and identify at least one clinical implication of each of the following key aspects of psychological aging: looking old but not feeling or thinking old, ageism, life review and adjustment to changes, the activity and disengagement theories of healthy aging, cognitive impairment, and the importance of relationships in older age. • Describe and identify at least one clinical implication of each of the following key aspects of health care provision involving older persons: multiple morbidity, function-oriented care, icebergs in geriatric assessment, iatrogenic disease, slow medicine, polypharmacy, the U.S. health care system, transitions in care, interprofessional care, and the value of a generalist in primary care geriatrics. Of course, the question of how to define old often depends on the age of the person you ask. A recent poll of 1000 adults aged 50 and older found that the majority thought middle age began at 55 and older age at 70.1 In ironic contrast is the fact that some of these same individuals had earlier in their lives subscribed to the catch phrase “never trust anyone over 30” that was popular among youth in the 1960s. In the past, medical providers were much more likely to write off symptoms such as these as normal (Box 1-1). In fact, research during recent decades has taught us that much of the disability that we used to attribute to “normal aging” is not normal at all. The way we now think about changes in aging is the rule of fourths (Figure 1-1). This rule states that, of changes often attributed to normal aging by the general public (and in past decades by the medical profession), about one fourth is due to disease, one fourth to disuse, one fourth to misuse, and only about one fourth to physiologic aging. Figure 1-1 The rule of fourths. In the past, all of the decline in function that occurs between young adulthood and old age was called normal aging. We now know that approximately one fourth can be attributed to disease, one fourth to disuse (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, lack of mental stimulation), and one fourth to misuse (e.g., smoking, injuries from contact sports, and adverse effects of prescription and/or recreational drugs). Only about one fourth can be attributed to physiologic aging. • If the problem is disease, then medical treatment is indicated. • If the problem is disuse, it can often be cured with an activity regimen. • If the problem is misuse, prior damage cannot be reversed but steps can be taken to prevent deterioration and to preserve function. • If the problem is physiologic aging, then steps should be taken to adapt and compensate for the disability. Whereas much of the change seen with aging results from causes other than physiologic aging, some changes are inevitable. Table 1-1 lists and describes many common physiologic changes noted with aging. Among the many notable changes are the following: TABLE 1-1 Some Common Anatomic and Physiologic Changes with Aging (in the Absence of Identified Disease) Adapted from Sloane PD. Normal aging. In: Ham RJ, Sloane PD, Warshaw GA, editors. Primary care geriatrics: A case-based approach. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Yearbook; 2002, p. 15-28. • The age at which reading glasses are needed because of reduced lens elasticity is between 42 and 50. • Vestibular sensitivity gradually increases until about age 60, which is one of the reasons why adults have increasing trouble on amusement park rides as they age. • Fertility in women peaks between 15 and 25 and declines thereafter, with menopause typically occurring about age 50. • Reaction time tends to increase with age (which explains why teenagers are usually far better at games of speed—including many video games—than older persons). • The amount of sway a person will experience if asked to stand still with his or her eyes closed is high in early childhood, is minimized between about ages 15 and 16, and then gradually increases beyond age 60. • Ankle jerk reflexes are increasingly diminished or absent with older age, in the absence of detectable musculoskeletal pathology. • Bone density plateaus between ages 20 and 50, then gradually declines, with the slope of decline being more rapid in women than in men. All body systems tend to have functional ability over and above what is used during everyday activities; this is called functional reserve. For example, the average adult’s cardiac output is around 5 L/min when sedentary, whereas the heart of a trained athlete is capable of generating 40 to 50 L/min.2 All other key body systems, such as the kidney, the lungs, the liver, and the brain, have reserve capabilities as well, so significant impairment from disease, disuse, misuse, or physiologic aging is needed to result in impaired function during normal activity. Clinically significant impairment in function occurs when demands exceed functional reserve. As people age, patterns of disease, disuse, misuse, and physiologic aging combine to decrease functional reserve. Among the losses in functional reserve that have particularly common implications in geriatric care are the following clinical situations: • Delirium is common in postoperative older persons, because brain functional reserve capacity is overwhelmed by the stress of the surgery and the persistence of anesthetic agents in the central nervous system and the bloodstream. • Nocturia is almost ubiquitous in older persons, largely because of changes in bladder physiology (decreased capacity and increased residual volume) combined with altered control of fluid excretion (related to low nighttime antidiuretic hormone levels and increased nighttime natriuretic polypeptide levels). • An older person will often fall when a younger person would not, because neuromuscular mechanisms to reestablish equilibrium from a minor perturbation (e.g., tripping on the edge of a rug) are impaired, often by a combination of disuse and normal aging changes in nerve conduction and vibratory sensation in the feet. One of the inexorable physiologic declines with aging is reduced stamina. An insidious reduction in stamina occurs, beginning in one’s 20s and terminating in advanced age (Figure 1-2). Of course, this gradual decline in stamina and fatigue can be accelerated by disease, disuse, and misuse; however, gradual decrease in stamina and need for more frequent rest is a universal phenomenon as one ages. This is why medical interns in their 20s can pull an all-night shift much more easily than they would be able to if asked to follow the same schedule when in their 50s. Figure 1-2 Inability to party all night is one of the earliest signs of aging. With increasing age and disability, diminished stamina can progress to the point where the older person no longer has enough energy to complete the necessary activities of daily living. This severe fatigue is the cardinal symptom of the frailty syndrome. When reduced stamina and fatigue are so great that they become the defining feature of one’s physiologic status, we refer to this as frailty. A commonly accepted, evidence-based definition of frailty is that of Fried et al.; it defines frailty as the occurrence of three or more of the following: unintentional weight loss (10 lbs in past year), self-reported exhaustion, weakness (reduced grip strength), slow walking speed, and low physical activity.3 One can see that all but the first of these criteria are manifestations of reduced stamina and fatigue. Frailty is a common and important geriatric syndrome (see Chapter 29). Another characteristic of aging is that, with advancing age, physiologic diversity increases. Indeed, the range of “normal” (i.e., the range that encompasses the performance of 95% of people) becomes increasingly wide as populations age. When we say, for example, “Jason is a normal 5-year-old,” we have a pretty good idea what Jason can and cannot do. The same is true at age 20. However, with each advancing decade the range of normality becomes wider (Figure 1-3), to the point that saying, “George is a normal 75-year-old,” tells you practically nothing about George other than how long ago he was born. Figure 1-3 As people age they become more diverse. This explains why individualized care rather than protocol-based care is especially important in the geriatric population. This increased diversity with age has many clinical implications. For example, it is easy to develop age-related guidelines for children, because, except in rare cases of chronic or developmental illness, age predicts performance in children. In older adults, however, age is not very helpful in determining health care norms or needs. In geriatrics, however, age-related protocols and guidelines are virtually nonexistent, and the clinician must individualize most aspects of assessment, goal setting, and care planning. In health care it is useful to think about three distinctive types of environments: the physical environment, the social environment, and the organizational environment.4 The physical environment refers to the physical setting in which a patient lives; it includes such things as size and decor of spaces, lighting, temperature, acoustic properties, and access to outdoors. The social (caregiving) environment refers to the people who interact directly with the patient—how they approach the person and what they do. The organizational environment refers to rules and regulations that affect a patient’s life, such as when they can eat, whether and how they can go outdoors, and what type and amount of services they receive. Needless to say, these environmental characteristics can have a huge impact not only on function but on quality of life for a dependent older person. • Doorknobs that are levers can markedly improve ease of door use for persons with arthritis. • Widened doorways can permit entry for persons in wheelchairs. • Motion sensors that turn on lighting can help prevent falls at night among cognitively or physically impaired older persons. A movement to improve the usability of housing for seniors and persons with disabilities is called universal design. A simplification of universal design is visitable housing, which is a movement to have all housing units built in such a way that they can be visited by people with disabilities, which includes many older adults. Visitable housing includes these three basic features: at least one no-step entrance, doors and hallways that are wide enough to navigate through in a wheelchair or walker, and a bathroom on the first floor big enough to get into in a wheelchair and close the door.5 Wheelchairs are part of the problem. They are useful for transportation, making it easier for disabled persons to get around, but they increase the risk for many medical complications and adverse events, which they share with overall sedentary existence. Among these complications are muscle atrophy, increased risk of constipation, increased risk of pressure sores, increased risk of urinary tract infections (caused in part by bladder outlet obstruction from constipation), decreased involvement in activities, and increased risk of radial nerve palsy.6,7 In summary, the physiologic changes of aging place older persons at a heightened risk for a permanent loss of function if they are kept in bed or in a wheelchair for as short a time as a week or two. So as soon as an older person can get up, he or she should be cajoled into getting up, and as long as an older person can be cajoled to walk, he or she should walk. For older persons, the well-known statement “Use it or lose it” could be extended to “Use it or lose everything.” For example, in a study of near-retirement physicians about their interest in volunteering during retirement, more than a third (37%) expressed interest in volunteering. However, working with older populations in assisted living, nursing homes, or hospice settings was not what fired them up—fewer than 4% expressed interest in this type of engagement. Instead, they tended to be interested in free clinics, disaster relief, international service, and medical teaching.8

Principles of primary care of older adults

Aging and the body

The rule of fourths

Normal physiologic changes

System or Function Affected

Change Noted

Body composition:

Percent body water

Percent body fat

Decreased

Increased

Brain:

Weight

Anatomy

Decreases by 7%

“Atrophy” commonly noted

Sleep patterns

Markedly reduced stage 3 and 4 sleep

More frequent awakenings; reduced sleep efficiency

Vision:

Lens accommodation

Amount of light reaching the retina

Color perception

Markedly reduced after age 40-50

Diminished by up to 70%

Reduced intensity (especially of blues and greens)

Hearing

Acuity declines beginning about age 12, with decline steepest in high pitches (>5000 Hertz [cycles/second])

Taste:

Number of taste buds

Changes in preferences

Reduced by 70%

Increased tolerance for very sweet and very salty foods (as a result of reduced perception)

Cardiac function:

Maximum heart rate

Reduced from about 195 to about 155 beats/min

Renal perfusion

Decreased by 50%

Bone mineral content

Diminished by 10%-30%

Prostate gland anatomy

Size increases by 100%

Sexual function:

Men

Women

Reduced intensity and persistence of erections; decreased ejaculate and ejaculatory flow

Menopause; reduced lubrication; vaginal atrophy

Functional reserve

Reduced stamina and fatigue

Increased physiologic diversity

Environment and function

Immobility

Aging and the mind

Looking old but not feeling or thinking old

Principles of primary care of older adults