Principles of Healthcare Epidemiology

Frances J. Boly

Victoria J. Fraser

Jennie H. Kwon

Epidemiology is defined as the study of the factors determining the occurrence of disease in human populations. Epidemiology is an indispensable tool for characterizing infectious diseases in medical institutions, communities, countries, and worldwide. Epidemiologic methods are necessary to determine the exposure-disease relationship and modes of acquisition and transmission that are critical for treatment, control, and prevention of infectious disease. Clinicians, microbiologists, and other personnel involved in public health and disease prevention professions use epidemiologic methods for disease surveillance, outbreak investigations, infectious diseases outcome measurements, and observational studies to identify risk factors for various infectious diseases. Knowledge of these risk factors is essential for making decisions regarding further epidemiologic or microbiological investigations, directing research activities, implementing relevant prevention and control measures or interventions, and establishing public health policies. In the pharmaceutical and biomedical industries, the application of epidemiologic methods is integral to the investigation of product contamination, ascertainment and characterization of risk factors for contamination, and maintenance of quality assurance practices in the laboratory or manufacturing operations to ensure safe distribution of products.

The use of epidemiology and the use of statistical methods to analyze epidemiologic data grew out of attempts to understand, predict, and control the great epidemics of the past; the diseases associated with those early epidemics were largely infectious. The study and implementation of infection control and prevention practices and interventions in hospitals were developed to understand and control the acquisition of infectious diseases that were initially described due to Staphylococcus aureus outbreaks in hospitals in the 1950s.1,2 Thus, discussion of the principles of epidemiology begins with examples of methods that were first formalized in the study of transmissible microorganisms, many of which continue to cause problems today.

The term hospital epidemiology was coined by professionals in the United States,3 as was the recognition of the use of epidemiologic methods for the study and control of noninfectious diseases in hospitals.4 The term nosocomial infection has traditionally defined acute infections acquired in hospital inpatient settings.5 However, in the current era of managed care, healthcare systems in the United States have evolved from traditional acute care hospital inpatient settings to more integrated, extended care models that now encompass hospitals, outpatient clinics, ambulatory centers, long-term care facilities, and the community. As expected, infections may be acquired at any of these levels of care. For this reason, the term nosocomial infection has been replaced by healthcare-associated infection (HAI).6

The terms hospital epidemiology and infection control and prevention remain synonymous in the minds of many, and both the terms and their associated programs have grown in definition and scope over the past five decades. With advances in the medical field and technology, interest in infection control and prevention has broadened from an initial focus on puerperal sepsis and surgical site infections to full, scientifically tested programs of surveillance, prevention, and control of all types of HAIs. Hospital epidemiology programs were among the first hospital disciplines to demonstrate the utility of the scientific method and statistics to characterize and analyze infectious diseases data and use the results of these analyses to improve the quality of healthcare and patient outcomes. In the special environment of the acute care hospital, a natural repetition of

earlier studies of population-based infectious disease outbreaks provided the basis for epidemiologic investigations.

earlier studies of population-based infectious disease outbreaks provided the basis for epidemiologic investigations.

Surveillance data generated from epidemiologic studies may be used to determine the need for clinical or public health action; assess the effectiveness of prevention, intervention, or control programs, or diagnostic algorithms; or set priorities for rational or appropriate use of limited microbiology resources, planning, and research. An understanding of epidemiology is important to quantify and interpret microbiology and pharmaceutical data and to apply these data to clinical practice, quality assurance, and hypothesis generation during investigation of outbreaks and other adverse events. Epidemiology is also an important foundation for rational medication prescribing policies, antimicrobial stewardship, and other public health measures.

Data from epidemiologic and microbiological studies can inform diagnostic and therapeutic practice and indicate areas for allocation of scarce resources. For example, one of the perennial problems that clinicians and microbiologists face is how to differentiate between a true bloodstream infection (BSI) and blood culture contamination resulting from coagulase-negative Staphylococci, which are the most frequently isolated microorganisms in blood cultures.7,8,9 Blood culture contamination can occur during venipuncture with inadequate antisepsis of the skin, after the blood draw at the time of inoculation of blood into the culture bottle, or during processing of blood culture bottles in the microbiology laboratory. To make an informed decision about whether a positive blood culture is a true BSI vs contamination, clinicians and microbiologists need to be familiar with the epidemiology of BSIs in different clinical settings and be able to integrate these data with relevant clinical and microbiology information so that a decision can be made whether or not to initiate antimicrobial therapy.

DEFINITIONS

In the application and discussion of epidemiologic principles, standard definitions and terminology have been widely accepted.10,11,12 The definitions of some commonly used terms are outlined in this section:

Attack rate: A ratio of the number of new infections divided by the number of exposed, susceptible individuals in a given period, usually expressed as a percentage. Other terms are the incidence rate and the case rate.

Attributable mortality: Indicates that an exposure was a contributory cause of or played an etiologic role leading to death.

Attributable risk: The measure of impact of a causative factor. The attributable risk establishes how much of the disease or infection is attributable to exposure to a specific risk factor. Attributable risk is a proportion where the numerator is the difference between the incidence in exposed and unexposed groups and the denominator is the incidence for the exposed group.

Bias: The difference between a true value of an epidemiologic measure and that which is estimated in a study. Bias may be random or systematic. There are three common types of bias: selection bias, information bias, and confounding. Selection bias is a distortion in the estimate of effect resulting from the manner in which parameters are selected for the study population. Information bias depends on the accuracy of the information collected. Unrecognized, systematic bias presents the greatest danger in studies by suggesting relationships that are not valid.

Carrier: An individual (host) who harbors a microorganism (agent) without evidence of disease and, in some cases, without evidence of host immune response. This carriage may take place during the latent phase of the incubation period as a part of asymptomatic disease or may be chronic following recovery from illness. Carriers may shed microorganisms into the environment intermittently or continuously, and this shedding may lead to transmission. Shedding and potential transmission may be increased by other factors affecting the host, including infection by another agent.

Case: An individual in a population or group recognized as having a particular disease or condition under investigation or study. This definition may not be the same as the clinical definition of a case.

Case-fatality rate: A ratio of the number of deaths from a specific disease divided by the number of cases of disease, expressed as a percentage.

Cluster: An aggregation of relatively uncommon events or disease in time and/or space in numbers that are believed to be greater than expected by chance alone.

Colonization: The recovery or identification of a microorganism at a body site or sites without any overt clinical signs of inflammation, infection, or immune reaction in the host at the time that the microorganism is isolated. Colonization may or may not be a precursor of infection. Colonization may be a form of carriage and is a potential source of transmission.

Communicability: The characteristic of a human pathogen that enables it to be transmitted from one person to another under natural conditions. Infections may be communicable or noncommunicable. Communicable infections may be endemic, epidemic, or pandemic.

Communicable period: The time in the natural history of an infection during which transmission to other susceptible hosts may take place.

Confounding: An illusory association between two factors when, in fact, there is no causal relationship between the two. The apparent association is caused by a third variable that is both a risk factor for the outcome or disease and is associated with but not a result of the exposure in question.

Contact: An exposed individual who might have been infected through transmission from another host or the environment.

Contagious: Having the potential for transmission of an infectious pathogen.

Contamination: The presence of an agent (eg, microorganism) on a surface or in a fluid or material, therefore, a potential source for transmission.

Cumulative incidence: The proportion of at-risk persons who become diseased during a specified period of time.

Endemic: The usual level or presence of an agent or disease in a defined population during a given period.

Epidemic: An unusual, higher-than-expected level of infection or disease by an agent in a defined population in a given period. This definition assumes previous knowledge of the usual, or endemic, levels.

Epidemic curve: A graphic representation of the distribution of defined cases by the time of onset of their disease.

Epidemic period: The time period over which the excess cases occur.

Hyperendemic: The level of an agent or disease that is consistently present at a high incidence and/or prevalence rate.

Immunity: The resistance of a host to a specific agent, characterized by measurable and protective surface or humoral antibody and by cell-mediated immune responses. Immunity may be the result of specific previous experience with the agent (wild infection), from transplacental transmission to the fetus, or from active or passive immunization to the agent. Immunity is relative and governed through genetic control. Immunity to some agents remains throughout life, whereas for others, it is short-lived, allowing repeat infections by the same agent. Immunity may be reduced in extremes of age, through disease, or through immunosuppressive therapy.

Immunity: cell-mediated vs humoral: Cell-mediated immune protection, largely related to specific T-lymphocytic activity, as opposed to humoral immunity, which is measured by the presence of specific immunoglobulins (antibodies) in surface body fluids or circulating in the noncellular components of blood. Antibodies are produced by B lymphocytes, also now recognized to be under the influence of T-lymphocytic function.

Immunogenicity: An agent’s (microorganism’s) intrinsic ability to trigger specific immunity in a host. Certain agents escape host defense mechanisms by intrinsic characteristics that fail to elicit a host immune response. Other agents evoke an immune response that initiates a disease process in the host that increases cellular damage and morbidity beyond the direct actions of the microorganism itself. These disease processes may continue beyond the presence of living microorganisms in the host.

Incidence: The ratio of the number of new infections or disease in a defined population in a given period to the number of individuals at risk in the population. “At risk” is frequently defined as the number of potentially exposed susceptible persons. Incidence is a measure of the transition from a nondiseased to a diseased state and is usually expressed as numbers of new cases per thousands (1000, 10 000, or 100 000) per year.

Incidence rate or density: Similar to the incidence but members of the at-risk population may be followed for different lengths of time. Thus, the denominator is the sum of each person’s time at risk (ie, total person-time of observation).

Incubation period: The period between exposure to an agent and the first appearance of evidence of disease in a susceptible host. Incubation periods are typical for specific agents and may be helpful in the diagnosis of unknown illness. Incubation periods may be modified by extremes of dose or by variations in host immune function. The first portion of the incubation period following colonization and infection is frequently a silent period, called the latent period. During this time, there is no evidence of host response(s) and evidence of the presence of the infecting agent may not be measurable. However, transmission of the microorganism to other hosts, though reduced during this period, is a recognized risk (eg, chicken pox, hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]). Measurable early immune responses in the host may appear shortly before the first signs and symptoms of disease, marking the end of the latent period. Signs and symptoms of disease commonly appear shortly thereafter, marking the end of the incubation period.

Index case: The first case to be recognized in a series of transmissions of an agent in a host population. In semiclosed populations, as typified by chronic disease hospitals, the index case may first introduce an agent not previously active in the population.

Infection: The successful transmission of a microorganism to the host with subsequent multiplication, colonization, and invasion. Infection may be clinical or subclinical and may not produce identifiable disease. However, it is usually accompanied by measurable host response(s), either through the appearance of specific antibodies or through cell-mediated reaction(s) (eg, positive tuberculin test results). An infectious disease may be caused by the intrinsic properties of the agent (invasion and cell destruction, release of toxins) or by associated immune response in the host (cell-mediated destruction of infected cells, immune responses to host antigens similar to antigens in the agent).

Infectivity: The characteristic of the microorganism that indicates its ability to invade and multiply in the host. It is frequently expressed as the proportion of exposed patients who become infected.

Infestation: The presence of ectoparasites on the body (eg, scabies, lice).

Isolation: The physical separation of an infected or colonized host, including the individual’s contaminated body fluids and environmental materials, from the remainder of the at-risk population in an attempt to prevent transmission of the specific agent to the latter group. This is usually accomplished through individual environmentally controlled rooms or quarters, hand washing following contact with the infected host and environment, and the use of barrier protective devices, including gowns, gloves, and, in the case of airborne agents, an appropriate mask.

Morbidity rate: The ratio of the number of persons infected with a new clinical disease to the number of persons at risk in the population during a defined period, an incidence rate of disease.

Mortality rate: The ratio of those infected who have died in a given period to the number of individuals in the defined population. The rate may be crude, related to all causes, or disease-specific, related or attributable to a specific disease in a population at risk for the disease.

Odds: The ratio of the probability of an event occurring to the probability of it not occurring.

Pandemic: An epidemic that spreads over several countries or continents and affects many people.

Pathogenicity: The ability of an agent to cause disease in a susceptible host. The pathogenicity of a specific agent may be increased in a host with reduced defense mechanisms. For some agent-host interactions, the resultant disease is due to the effects of exaggerated or prolonged action of defense mechanisms of the host.

Prevalence: The ratio of the number of individuals measurably affected or diseased by an agent in a defined population at a particular point in time. The proportion of the population having the disease during a specified time period, without regard to when the process or disease began, defines the period prevalence.

Pseudo-outbreak: Real clustering of false infections or artifactual clustering of real infections. Often it is identified when there is increased recovery of unusual microorganisms.

Rate: An expression of the frequency with which an event occurs in a defined population. All rates are ratios. Some rates are proportions; that is, the numerator is a part of the denominator. A comparable rate is a rate that controls for variations in the distribution of major risk factors associated with an event.

Ratio: An expression of the relationship between a numerator and a denominator where the two are usually distinct and separate quantities, neither being a part of the other.

Relative risk: The ratio of the incidence rate of infection in the exposed group to the incidence rate in the unexposed group. Used to measure the strength of an association between exposures or risk factors and disease.

Reservoir: Any animate or inanimate niche in the environment in which an infectious agent may survive and multiply to become a source of transmission to a susceptible host. Medical care workers and patients constitute the main animate reservoir for microorganisms associated with HAIs; water-related reservoirs are important inanimate reservoirs that have been implicated in outbreaks related to dialysis units and to air conditioning systems.

Secular trend: Profile of the changes in measurable events or in the incidence rate of infection or disease over an extended period of time, also called a temporal trend.

Sensitivity: For surveillance systems, the ratio of the number of patients who were reported to have an infection divided by the number of patients who actually did have an infection (true positives over true positives plus false negatives).

Source: The animate or inanimate mechanism by which a pathogen is transmitted from their reservoir to a human (eg, the reservoir may be the soil, the source may be contaminated food). At times, the reservoir and source may be same (eg, sexually transmitted disease).

Specificity: For surveillance systems, the ratio of number of patients who were reported not to have an infection divided by the number of patients who actually did not have an infection (true negatives over true negatives plus false positives).

Sporadic: Occurring irregularly and usually infrequently over a period of time.

Surveillance: The ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of healthcare data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those contributing data or to other interested groups who need to know the data. Surveillance was popularized by Langmuir and others at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and has been an essential tool for infection control and prevention programs in the United States since the 1960s.

Susceptibility: A condition of the host that indicates absence of protection against infection by an infectious agent. This is usually marked by the absence of specific antibodies or specific measures of cell-mediated immunity against the infecting microorganism.

Transmission: The method by which any potentially infecting agent is spread to another host. Transmission may be direct or indirect. Direct transmission may take place by touching (direct contact transmission) between hosts, by the projection of large droplets in coughing and sneezing onto another host (droplet transmission), or by direct contact by a susceptible host with an environmental reservoir of the agent. Indirect transmission may be vehicle-borne, airborne, or vector-borne. In vehicle-borne transmission, contaminated environmental sources, including water, food, blood, and laundry, may act as an intermediate source of an infectious agent for introduction into a susceptible host. The infectious agent may have multiplied or undergone biologic development in the vehicle. In airborne transmission, aerosols containing small (1-5 µm) particles may be suspended in the air for long periods of time and then inhaled into the lower respiratory tract allowing replication of the infectious agent in a host. Airborne infectious particles may be generated by evaporation of larger particles produced in coughing and sneezing (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), by machines or equipment such as air conditioners or humidifiers that can generate aerosols (Legionella), or by wind or air currents (fungal spores). In vector-borne transmission, arthropods or other invertebrates may carry and subsequently transmit microorganisms, usually through inoculation of the host that occurs through biting the host or by contamination of food or other materials. The vector may be infected itself or only serve as mechanical carrier of the agent. If the vector is infected, the agent may have multiplied or undergone biologic development in the vector. Vector-borne transmission is an uncommon source of HAIs in the United States; however, vector-borne HAIs can occur in resource limited settings.

Virulence: The intrinsic capabilities of an agent to infect a host and produce disease and a measure of the severity of the disease produced. In the extreme, virulence is represented by the number of patients with clinical disease who develop severe illness or die, that is, the case-fatality rate.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC METHODS APPLIED TO INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Classic epidemiologic methods are essential for the study, characterization, and understanding of the various infections that occur in healthcare settings, communities, and broad geographic regions. Epidemiologic methods are used to determine the exposure-disease relationship in humans; establish the modes of acquisition, mechanisms of transmission, and spread; identify risk factors associated with infection and disease; characterize and relate causal factors to an infectious disease; determine or select appropriate methods of prevention and control; or guide rational application and practice of clinical microbiology methods. These epidemiologic methods were developed in an attempt to control common errors in observational studies

that occur when individuals study the association of one event (a risk or causal factor) with another later event (the outcome or disease).13,14,15,16

that occur when individuals study the association of one event (a risk or causal factor) with another later event (the outcome or disease).13,14,15,16

Epidemiologic study methods are grouped as either observational or experimental. Observational epidemiologic methods are further classified as either descriptive or analytic. Observational studies are conducted in natural, everyday community or clinical settings, where the investigators observe the appearance or an outcome but have no control over the environment or the exposure of people or product to a risk factor or suspected etiologic agent, a specific intervention or preventive measure, or a particular therapeutic regimen.

Descriptive Epidemiology

Observational descriptive studies establish the case definition of an infectious disease event by obtaining data for analysis from available primary (eg, medical records) or secondary (eg, infection control surveillance) sources. These data enable the characteristics of the population that has acquired the infection to be delineated according to (1) “person” (age, sex, race, marital status, personal habits, occupation, socioeconomic status, medical or surgical procedure or therapy, device use, underlying disease, or other exposures or events), (2) “place” (geographic occurrence of the health event or outbreak, medical or surgical service, place of acquisition of infection, or travel), and (3) “time” (preepidemic and postepidemic periods, seasonal variation, secular trends, or duration of stay in hospital). The information from descriptive studies might provide important clues regarding the risk factors associated with infection, and in each case, it is hoped that an analysis of the collected data might be used to generate hypotheses regarding the occurrence and distribution of disease or infection in the population(s) being studied.

Analytic Epidemiology

Observational analytic studies are designed to test hypotheses raised by the findings in descriptive investigations. The objectives of these studies are (1) to establish the cause and effects of infection in a population and (2) to determine why a population acquired a particular infection in the first place. The three most common types of observational analytic studies are cohort studies, case-control studies, and prevalence or cross-sectional studies.

Cohort Studies In cohort studies, hypotheses that have been generated from previous (descriptive) studies are tested in a new population. A population of individuals (a cohort) that is free of the infection or disease of interest is recruited for study. The presence or absence of the suspected (hypothesized) risk factors for the disease is recorded at the beginning of the study and throughout the observational period. All members of the cohort population (eg, all premature infants admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit [ICU] during a defined time period) are followed over time for evidence or appearance of the infection or disease and classified accordingly as exposed or unexposed to specific risk factors. If the observation period begins at the present time and continues into the future or until the appearance of disease, the study is called a prospective cohort study. If the population studied is one that in the past was apparently free of the markers of disease on examination of records or banked laboratory specimens, it may be chosen for study if data on exposure to the suspected risk factors for disease are also available. The population may be followed to the present or until the appearance of disease. This type of study, common in occupational epidemiology, is called a historical or retrospective cohort study.

A key requirement of a cohort study is that participants be reliably categorized into exposed and unexposed groups. Relative risk, that is, the ratio of the incidence of the outcome in the exposed group to the incidence in the unexposed group, is used to measure the strength of an association between exposures or risk factors and disease. Cohort studies have the advantage of enabling identification and direct measurement of risk factors associated with disease, determination of the incidence of infection and disease, and ascertainment of the temporal relationship between exposure and disease. In cohort studies, observational bias may be less of a limitation on the validity or results, since the information on the presence of risk factors is recorded before the outcome of disease is established. To ensure sufficient numbers for analysis, cohort studies require continual follow-up of large populations for long periods unless the disease under investigation is one of high incidence. Cohort studies are, in general, more expensive and time-consuming to conduct and are not suitable for the investigation of uncommon infections or conditions. However, they render the most convincing nonexperimental approach for establishing causation.

Case-Control Studies In a case-control study, individuals (cases) who are already infected, ill, or meet a given case definition are compared with a group of individuals (controls) who do not have the infection, disease, or other outcome of medical interest. In contrast to cohort studies, participants in a case-control study are selected by manifestation of symptoms and signs, laboratory parameters, or a specific condition, disease, or outcome. Thus, the search for exposure of case and control subjects to potential risk factors remains a retrospective one. For case-control studies, the measure of association between exposures or risk factors and health outcomes are expressed as an odds ratio, that is, the ratio of the odds of an exposure, event, or outcome occurring in a population to the odds in a control group, where the odds of an event is the ratio of the probability of it occurring to the probability of it not occurring.

The presence of significant differences in the exposure to risk factors among cases vs control subjects suggests an etiologic (causal) association between those factors and the infection or disease defined by cases. Case-control methods are useful for studying infections, events, or outcomes likely associated with multiple risk factors or low incidence rates; for investigating situations in which there is a long lag-time between exposure and outcome of interest; and for establishing etiologic associates or causation of a disease, infection, or other outcome when there is no existing information about the cause or source. In an attempt to reduce bias, control subjects might be selected from individuals matched with cases for selected characteristics, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, or other variables not suspected or under investigation as risk factors. Compared with cohort studies, case-control studies may be conducted in relatively shorter time, are

relatively less expensive, or may require a smaller samples size to execute. Limitations of case-control studies include selection bias in choosing cases and control subjects; recall bias in which study subjects might have difficulty in remembering possible exposures; incomplete information on specific exposures; or risk factor data may be difficult to find (or remember). Case-control studies are not used to measure incidence or prevalence rates and, generally, are not capable of establishing temporal relationships between an exposure and outcome.

relatively less expensive, or may require a smaller samples size to execute. Limitations of case-control studies include selection bias in choosing cases and control subjects; recall bias in which study subjects might have difficulty in remembering possible exposures; incomplete information on specific exposures; or risk factor data may be difficult to find (or remember). Case-control studies are not used to measure incidence or prevalence rates and, generally, are not capable of establishing temporal relationships between an exposure and outcome.

Prevalence or Cross-sectional Studies In prevalence studies, the presence of putative risk factors and the disease under investigation is recorded in a survey of a study population at a specific point in time or within a (short) time period. The rates of disease among those with and without the suspected risk factors are compared. Thus, cross-sectional studies can establish association but not causation for suspected risk factors. Prevalence studies are relatively inexpensive and can be carried out rapidly if well planned. However, they do not allow the ascertainment of risk factors at the beginning of disease nor do they enable one to establish a temporal sequence of risk factors preceding the infection or other outcome of interest. Point prevalence, period prevalence, and seroprevalence surveys are examples of cross-sectional studies.

Experimental Epidemiology

In experimental studies, the investigator compares an exposure of individuals in a population to a suspected causal factor, a prevention measure, a therapeutic regimen, or some other specific intervention. These exposure modalities are randomly allocated to comparable groups, thereby minimizing confounding factors. Both the exposed and unexposed groups are monitored thereafter for specific outcomes (eg, appearance of infection or disease, evidence of effective prevention or control of the disease, or cure). Experimental studies often are used to evaluate antimicrobial or vaccine treatment regimens and are generally more expensive to conduct than observational studies. Within healthcare settings, studies that examine restriction of certain antimicrobials or promotion of use of alternative antimicrobials for the control of antimicrobial resistance could be considered under the category of experimental. For ethical reasons, it is rarely possible to expose human populations to potential pathogens or to withhold a preventive measure that could potentially be beneficial to patients. Unfortunately, many animal hosts are not naturally susceptible to many agents of human disease. Thus, one has to be careful when extrapolating epidemiologic findings in animal experimental studies to the control of infections in human subjects.

Quasi-experimental studies: This type of study shares the design characteristics of experimental studies but lacks random assignments of study subjects. Quasi-experimental studies are useful where randomization is impossible, impractical, or unethical. The main drawbacks of quasi-experimental studies are their inability to eliminate confounding bias or establish causal relationships. The most common quasi-experimental design is the beforeafter study in which there is a baseline measurement of the outcome (prospectively or retrospectively) followed by an intervention with measurement of the outcome and an assessment whether the intervention altered the outcome.

Machine Learning

In the United States, the implementation and integration of electronic medical records into many inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings has led to an unprecedented quantity of healthcare data. Electronic health record (EHR) data can be used to improve infection control and prevention and allocation of hospital resources. Machine learning is the study of tools and methods for identifying patterns in data. It is becoming increasingly used for healthcare projects for risk stratification for specific infections, identifying the relative contribution of specific risk factors to overall risk, understanding pathogen-host interactions, and predicting emergence and spread of infectious diseases.17 Machine learning can be divided into two subareas: supervised and unsupervised learning. In supervised learning, the input data and target outcomes are observed. An example is classifying patients as either diseased or healthy. A domain expert (eg, a physician) assigns a label to each patient. The aim being to find a model that best distinguishes between the two classes, to either correctly assign the label or new patients or to identify important covariables. In unsupervised learning, the data consist of input variables without a corresponding outcome label. The goal is to find patterns and extract hidden data without expert labeling.18 An example of unsupervised learning is detection of patients with hospital-acquired infections and finding similar patient subgroups to assign patients to clinical trials. Numerous studies have incorporated machine learning to the field of infectious diseases including predicting the risk of nosocomial Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) using clinical data from the EHR, prediction of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), predicting reservoirs of zoonotic diseases using information on rodent species, and predicting clinical outcomes in Ebola virus using clinical symptoms.17 There are numerous challenges to applying machine learning for the purposes of hospital epidemiology. Given the potential inconsistencies and inaccuracies of health data, significant time can be required to extract and reprocess data before it can be used for machine learning. Machine learning with big data is not a replacement for a randomized control trial. No matter how detailed the measurements in EHR data, unmeasured factors cannot always be captured and observational studies of EHR data lack the ability to identify causal inference.19

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF INFECTION AND DISEASE

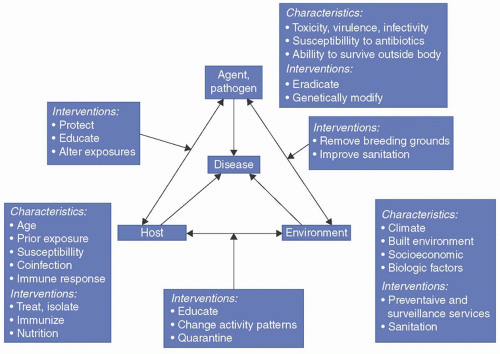

The epidemiology of infectious disease presents two processes for discussion: (1) the epidemiology of the determinants leading to infections in hosts and (2) the epidemiology of the appearance and extent of disease related to the infection in those hosts. It is common to discuss health and disease as the result of a series of complex interactions between an infectious agent, the host that is the target of the infectious agent’s actions, and the mutual environment in which the host and infectious agent exist. In studies of HAIs, the infectious agents are the microorganisms associated

with the infections, the hosts are the patients or healthcare personnel (HCP), and the common environment is the acute care hospital, ICU, outpatient, home, or other healthcare setting.

with the infections, the hosts are the patients or healthcare personnel (HCP), and the common environment is the acute care hospital, ICU, outpatient, home, or other healthcare setting.

FIGURE 1-1 The “epidemiologic triad” of infectious disease summarizes the factors that influence an infection and the measures you might take to combat the infection. (From Johnson Y, Kaneene J. Epidemiology: From Recognition to Results. 2018:1-30. Ref.21)

|

The interactions determining the probability of a microbiologic agent causing infection in a host may be simply presented by an equation of infection:

where Ip is the probability of infection, D is the dose (number of microorganisms) transmitted to the host, S is the receptive host site of contact with the agent, T is the time of contact (sufficient for attachment and multiplication or not), and V represents virulence, the intrinsic characteristics of microorganism that allow it to infect. The denominator in the equation (Hd′) represents the force of the combined host defenses attempting to prevent the infection.

Any reduction in host defenses (represented by the denominator) in such an equation allows infection to take place with a similar reduction in one or more of the infectious agent factors in the numerator. Infection may take place with a smaller dose of microorganisms. Infection may take place at an unusual site. The contact time for a microorganism to attach to an appropriate surface may be shorter, or infection may take place with an agent of lesser virulence, one that does not cause infection in a normal host. Reductions in the host defense characteristics, represented by the denominator, and the reduction of requirements to infect for the agent are typical of the interactions that facilitate opportunistic infections in compromised hosts, increasing numbers of whom receive medical and surgical care in modern hospitals. In the equation of infection, the environment might be considered the background on which the infectious agent-host interaction takes place.20 A number of additional models of the interaction of agent, host, and environment have been suggested to help understand these processes. The model in Figure 1-1, the triangle model, attempts to visualize the interplay between the three components of the host pathogen and environment.

INTERACTIONS OF AGENT, HOST, AND ENVIRONMENT

There are often multifactorial causes that lead to outcome events (infection or disease). For some infectious diseases, a single unique factor or agent is necessary and sufficient for the disease to appear. This is exemplified by measles or rabies. It is only necessary for the host to be exposed to and infected by an agent (the measles virus or rabies virus) for that disease to develop. For other infectious diseases, the single factor of infectivity of the agent is necessary but not sufficient to cause disease in the host. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M tuberculosis), polio virus, hepatitis A, and many other agents necessary for specific disease in a human host can infect hosts without causing disease in many cases. Within the hospital setting, exposure to a specific microorganism or colonization of an inpatient with an agent, such as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) or S aureus, may be necessary but not sufficient to generate disease. For VRE and S aureus, disease generally develops as a result of complex interactions between contributing factors, such as age, state of debilitation, immune or nutritional status, device use, invasive procedures, antimicrobial usage, or susceptibility of the microorganism to available antimicrobials. The presence of the infection in these cases is not always sufficient to produce disease in the host without the contribution of additional host or environmental factors.

Agents

The agents causing healthcare-associated infectious diseases are diverse microorganism ranging in size and

complexity from viruses and bacteria to protozoa and helminths. Bacteria, fungi, and certain viruses have been the most recognized and studied causes of HAIs.22 For transmission to take place, microorganisms must remain viable in the environment until contact with the host has been sufficient to allow infection. Reservoirs that allow the agent to survive or multiply may be animate, as exemplified by HCP carriage of S aureus in the anterior nares or throat,23 or inanimate as occurs in the environment, as demonstrated by Pseudomonas spp. colonization of sink areas, Legionella in hot and cold water supply systems,24 C difficile spores on computer keyboards,25 or Serratia marcescens growing in contaminated soap or hand lotion preparations.26

complexity from viruses and bacteria to protozoa and helminths. Bacteria, fungi, and certain viruses have been the most recognized and studied causes of HAIs.22 For transmission to take place, microorganisms must remain viable in the environment until contact with the host has been sufficient to allow infection. Reservoirs that allow the agent to survive or multiply may be animate, as exemplified by HCP carriage of S aureus in the anterior nares or throat,23 or inanimate as occurs in the environment, as demonstrated by Pseudomonas spp. colonization of sink areas, Legionella in hot and cold water supply systems,24 C difficile spores on computer keyboards,25 or Serratia marcescens growing in contaminated soap or hand lotion preparations.26

Certain intrinsic and genetically determined properties of microorganisms are important for their survival in the environment. Intrinsic and genetic properties that enhance survival include the ability to resist the effects of heat, drying, ultraviolet light, or chemical agents, especially antimicrobials, and the ability to independently multiply in the environment or to develop and multiply within another host or vector. Intrinsic infectious agent factors important to the production of disease include infectivity; pathogenicity; virulence; the infecting dose; the infectious agent’s ability to produce toxins; its immunogenicity and ability to resist or overcome the human immune defense system; its ability to replicate only in certain types of cells, tissues, or hosts (vectors); its ability to persist or cause chronic infection; and its interaction with other host mechanisms, including the ability to cause immunosuppression (eg, HIV).

Once transferred to a host surface, infectious agents may multiply and colonize without invading or evoking a measurable host immune response.27 The presence of an infectious agent at surface sites in the host does not define the presence of an infection. Nonetheless, colonized patients may act as the reservoir and/or source of transmission to other patients or HCP.28

If infection takes place, a measurable immune response will develop in most hosts even if the infection is subclinical. The likelihood of infectious agents causing infections is increased in nonimmune hosts, and infections are most likely to occur in nonimmune, immunocompromised hosts. A microorganism’s ability to infect another host vector (eg, yellow fever virus in mosquitoes) or another nonhuman reservoir (eg, yellow fever virus in monkeys) is important in the epidemiology of certain infectious diseases globally but plays little role in the epidemiology of HAIs where vector-borne infectious diseases are uncommon and where hospital settings have sealed windows/doors and controlled heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in the United States.

Host

Infection depends on exposure of a susceptible host to an infecting agent. Exposure of the susceptible host to such agents is influenced by age, behavior, family associations, occupation, socioeconomic level, travel, avocation, access to preventive healthcare, vaccination status, or hospitalization. Whether or not disease takes place in the infected host and the severity of disease when it occurs depends not only on the intrinsic virulence factors of the infectious agent but also more importantly on the pathogenicity of the infectious agent and host pathogen interactions. The host immune defenses exist to prevent infection. Thus, any reduction in host defenses may allow infection to take place with a smaller dose of microorganisms or at a body site that is not usually susceptible to infection. A combination of reductions in host defense characteristics and the requirements for an agent to cause infection are typical of the interactions that allow acquisition of opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients.29,30

Host factors important to the development and severity of infection or disease may be categorized as intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic factors include the person’s age at infection; birth weight; sex; race; nutritional status31; comorbid conditions (including anatomic anomalies) and diseases; genetically determined immune function; immunosuppression associated with other infections, diseases, or therapy; vaccination or immunization status; previous exposure or infection with an infectious agent or similar agents; and the psychological state of the host.32,33 Colonization of the upper and lower respiratory tracts is more likely when the severity of illness increases in critically ill patients. This, along with other host impairments (eg, reduced mucociliary clearance or changes in systemic (pH), allows colonization to progress to invasive infection. Moreover, other clinical conditions may lead to an alteration in epithelial cell surface susceptibility to binding by bacteria, leading to enhanced colonization.27 Extrinsic factors include invasive medical or surgical procedures, the presence of medical devices, such as intravenous catheters or mechanical ventilators, specific behaviors such as sexual practices and contraception, duration of antimicrobial therapy and hospitalization, and exposure to hospital personnel.

Environment

The environment serves as the background on which infectious agent-host interactions take place. Environmental factors can positively or negatively influence the spread of infection. Environmental factors that influence the spread of infection include (1) physical factors such as climate conditions of heat, cold, humidity, seasons, and the built environment (eg, ICUs, outpatient clinics, long-term care [LTC] facilities, or water reservoirs); (2) biologic factors (eg, the presence or absence of intermediary hosts such as insect or snail vectors, presence of biofilms in sinks or devices); and (3) social factors (eg, socioeconomic status, types of food and methods of preparation, and availability of adequate housing, potable water, adequate waste disposal, and healthcare amenities).34 These environmental factors influence both the survival and the multiplication of infectious disease agents in their reservoirs and the behavior of the host in housing, occupation, and recreation that relate to exposure to pathogens. Food- and waterborne diseases flourish in warmer months due to better incubation temperatures for microorganism multiplication and the recreational exposures of the host, whereas respiratory agents appear to benefit from increased opportunities for airborne and droplet transmission in the reduced humidity and closer living environments during the winter. In U.S. hospitals, the frequency of hospital-acquired Acinetobacter spp. infections is increasing in ICUs. The seasonal variation in the incidence of Acinetobacter spp. infections is thought to be due to changes in climate since the number of Acinetobacter spp. infections identified increases in the summer months.35

Within healthcare settings, the components of the agent, host, and environment triad interact in a variety of ways to produce HAIs. For example, ICUs are now considered the areas with the highest risk for the transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens in U.S. hospitals.36,37 Moreover, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), VRE, extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing E coli and Klebsiella, and β-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa are endemic in many ICUs in these hospitals.36,37 The emergence of vancomycin-resistant S aureus (VRSA) in U.S. institutions in 2002 highlighted the unwelcome but inevitable reality that VRSA may become endemic in acute care settings.38,39 A complex interaction of contributory factors, such as inadequate hand hygiene and suboptimal infection control practices among HCP, fluctuating staffing levels, an unexpected increase in patient census relative to staffing levels in the ICU, or an unprecedented increase in the number of severely ill patients with multiple invasive devices, could all contribute to the acquisition of hospital or long-term care facility infections caused by one of these endemic microorganisms.40,41,42,43,44 Adding to the complexity of the process would be the unquantifiable mechanism of transmission of the agent from the host to HCP, HCPto-HCP, and host-to-environment. Thus, acceptable measures for the prevention and control of HAIs dictate that healthcare epidemiologists study and analyze the interrelationships among all components of the triad of agent, host, and environment.36,37

It is well known that the social environment is important in influencing personal behavior that affects the direct transmission of agents, such as HIV transmission to infants from nursing mothers via breast milk in regions of high HIV endemicity, Gram-negative microorganisms transmitted via artificial nails worn by HCP in U.S. ICUs,43,45 and increased risk of sexually transmitted infections among vulnerable populations who cannot always use condoms or other barrier protection or do not have access to preexposure prophylaxis. What must be understood to be equally relevant is the impact of other factors in the social environment, such as the distribution of and access to medical resources; the use of preventive services46,47,48,49,50; the enforcement of codes in food preparation, infection prevention practices, or occupational health practices; the extent of acceptance of breast-feeding for children51,52,53; and the acceptance of advice on the appropriate use of antimicrobials.54,55,56,57,58 Also, there must be an appreciation by patients, relatives, and healthcare providers alike that at-risk patients (eg, those born very prematurely, the very elderly, or those with premorbid end-stage cardiac or pulmonary disease) who have numerous indwelling catheters or invasive devices, or who have undergone multiple invasive or surgical procedures will be particularly susceptible to HAIs that are likely nonpreventable.

Special Environments

Microenvironments, including military barracks, dormitories, day care centers, LTC settings, ambulatory surgery and dialysis centers, and acute care hospitals, provide special venues for infectious agent-host interactions. Historically, epidemics in these institutional environments provided the experience that drove the development and acceptance of infection control and prevention measures, guidelines, and the need for formal infection control resources and infrastructure. Acute care hospitals, especially those offering regional, secondary, and tertiary care, remain the dominant examples of high-risk environments. Changing patterns of outpatient practice, home healthcare, and technical advances in medicine have resulted in increasingly severely diseased and injured populations being managed in acute care facilities. Data from the CDC demonstrate that the changing healthcare environments in the United States are resulting in increasing numbers of ICU patients, while there has been a general decrease in the number of general medical beds.22

Special units for intensive medical or surgical care for extensive burns, trauma, transplantation, and cancer chemotherapy frequently care for patients with increased susceptibility to infection.59 In these susceptible patients, reduced inocula of pathogens or commensals are required to cause infection, infection may take place at unusual sites, and usually nonpathogenic agents may cause serious disease and death. Frequent opportunistic infections in these patients often require repeated, broad-spectrum, and extended therapy with multiple antimicrobials, leading to increasingly resistant resident microbial populations.22,57,58 The emergence in ICU settings of pathogens resistant to all available antimicrobials is becoming more common.36 For example, P aeruginosa has the capability to acquire new resistance mechanisms through horizontal transfer or chromosome mutations. This can occur while the patient is actively being treated and result in antibiotic failure and lead to mortality.60 Additionally, VRE colonization and contamination in the ICU has been associated with transmission to other patients.61

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) was originally developed in the 1970s to treat cystic fibrosis patients. OPAT gives patients the opportunity to have central venous catheters (CVC) placed and kept in situ for intravenous home infusion therapy to avoid prolonged hospital stays. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) has published guidelines listing requirements for teamwork, communication, monitoring, and outcome measurements in order to establish an effective and safe OPAT program.62,63 The benefit of OPAT is reduced exposure to hospital environments and decreased costs to patients, hospitals, and payers. OPAT also offers significant benefits to patients. It reduces their hospital stays and allows them to be in the familiar setting of their own home. Patients also learn to become advocates for their own health and ensure that appropriate and complete treatment is provided. On the other hand, a patient with a CVC in the home environment may potentially be at risk of CLABSI due to contamination of lines, dressings, and infusates in a care environment where infection control practices are not as well understood, practiced, or regulated. Some studies have reported readmission rates above 20% in patients participating in OPAT because of worsening infection, adverse drug reactions, and catheter-related complications. Recent studies have suggested that early infectious disease follow-up was associated with a lower 30-day hospital readmission rate.64

INFECTION, COLONIZATION, AND SPECTRUM OF DISEASE

Infection is the successful transmission of a microorganism to a susceptible host, through a suitable portal of entry, with subsequent colonization, multiplication, and invasion. The source of a microorganism (the primary reservoir) may be animate (eg, humans, mammals, reptiles, or arthropods) or inanimate (eg, work surfaces, toys, false fingernails, toiletries, or soap). Disease is the overt damage done to a host as a result of its interaction with the infectious agent; it represents a clinically apparent response by or injury to the host after infection, with the affected person showing symptoms or physical signs that may be characteristic of infection with the invading pathogen. Thus, disease is the outcome of an infectious process, and a pathogen is any microorganism with the capacity to cause disease in a specific host.

Unapparent or subclinical infection is a frequent occurrence in which the infected person may not manifest any symptoms, signs, disability, or identifiable disease. For example, subclinical Plasmodium falciparum infections in patients from Bangladesh can serve as a reservoir for malaria infection.65 In patients who acquire Salmonella typhi infection (typhoid fever), a chronic infection of the gallbladder may develop with asymptomatic fecal excretion of the pathogen for years after the acute infection.66 Patients in HIV-endemic countries may have M tuberculosis BSIs despite having normal chest radiographs and no symptoms or signs suggestive of underlying pulmonary disease.67,68 Persons with subclinical infection are sometimes referred to as carriers. Subclinical infection may be recognized through laboratory testing of blood or other appropriate body material from the host. These tests may indicate evidence of an immune response to infection, the presence of antigens characteristic of the microorganism, abnormal cellular function in response to infection, or the presence of the microorganism itself.

Colonization is the presence of a microorganism in or on a host, with growth and multiplication, but without any overt clinical expression or detected immune reaction in the host at the time the microorganism is isolated. An infectious agent may establish itself as part of a patient’s flora or may cause low-grade chronic disease after an acute infection. For example, 20% of healthy adults are persistent carriers of S aureus in the anterior nares without any manifestation of clinical illness. However, under suitable conditions, patient populations colonized with S aureus are at an increased risk of developing infections and disease.69,70,71,72 Once colonization or infection is established in a susceptible host, the infectious agent may enter a silent or latent period during which there is no clinical or typical laboratory evidence of its presence. Thereafter, the host may manifest signs and symptoms of mild disease without disability, exhibit rapid or slow progression of disease, or progress to either temporary or chronic disability. Ultimately, the patient may die or have a complete recovery and return to health without sequelae.

The outcome of an infection is determined by the size of the infecting dose, the site of the infection, the vaccination status of the host, the speed and effectiveness of the host immune response, other intrinsic host factors (eg, nutritional status), and promptness of instituting and effectiveness of the therapy. These factors together with intrinsic properties of a microorganism, such as its infectivity, pathogenicity, virulence, and incubation period, determine the course and progress of an infection and manifestation of disease. Infectivity is the characteristic of the microorganism that indicates its ability to invade and multiply in a susceptible host to produce infection or disease. Infectivity is expressed as the proportion (ie, the attack rate) of patients who become infected when exposed to an infectious agent. The basic measure of infectivity is the minimum number of infectious particles required to establish infection. Pathogens like Ebola, polio, or measles viruses have high infectivity.

The pathogenicity of an infectious agent is a measure of its ability to cause disease in a susceptible host. Thus, while the measles virus has a relatively high pathogenicity (ie, few subclinical cases), the poliovirus has a low pathogenicity (ie, most cases of polio are subclinical). The measure of pathogenicity is the proportion of infected persons with clinically apparent disease. The pathogenicity of an infectious agent that is usually innocuous may be increased in a host with reduced defense mechanisms. For some infectious agent-host interactions, the resultant disease is due to the effects of exaggerated or prolonged host defense mechanisms. The virulence of a microorganism is its intrinsic capability of infecting a host to produce disease. It follows that a pathogen might have varying degrees of virulence. Thus, although the nonencapsulated form of Haemophilus influenzae is a common inhabitant of the upper respiratory tract of healthy humans and causes localized infection without bacteremia (eg, conjunctivitis or otitis media in children), the more virulent encapsulated type b form causes more invasive disease and is an important cause of meningitis or epiglottitis. The incidence of H influenzae infection in the United States has dramatically decreased with the introduction of the H influenzae b vaccine. If the disease is fatal, virulence can be measured with the case-fatality rate. For example, the rabies virus almost always produces fatal disease in humans and is therefore an extremely virulent agent.

The ability to diagnose an infection or disease depends on the degree to which typical symptoms and physical signs develop in patients, the appropriateness of diagnostic tests, and the sensitivity and specificity of these tests for the particular infecting agent. Whether an infecting agent produces clinical or subclinical infections depends on the agent and host factors, for example, age or immune status. For example, P aeruginosa, a ubiquitous pathogen that thrives in aquatic environments and vegetation, seldom causes disease in healthy humans. However, in debilitated, hospitalized patients, such as those with burns, critical care patients with multiple invasive medical devices, or those who are on prolonged mechanical ventilation, P aeruginosa has become an important cause of HAIs in U.S. hospitals.73,74,75,76

Certain agents may be associated with a variety of different syndromes that depend on age and vaccination status of the host, previous infection with the agent, and agent-related mechanisms that remain unclear. Thus, Strongyloides spp., a nematode that is endemic in many parts of the world, including Southeast Asia and some

parts in southeastern United States, can cause asymptomatic infection or be associated with several syndromes ranging from mild epigastric discomfort and chronic skin rashes to life-threatening hyperinfection that results in a Gram-negative BSI, pneumonia, and multisystem disease in immunosuppressed patients, including solid organ transplant recipients or patients with chronic airway disease who are steroid-dependent.77,78,79 These differences in host-agent interactions underscore the difficulty in establishing causation and the importance of confirmatory laboratory evidence to precisely identify the causal agent associated with infectious disease syndromes.

parts in southeastern United States, can cause asymptomatic infection or be associated with several syndromes ranging from mild epigastric discomfort and chronic skin rashes to life-threatening hyperinfection that results in a Gram-negative BSI, pneumonia, and multisystem disease in immunosuppressed patients, including solid organ transplant recipients or patients with chronic airway disease who are steroid-dependent.77,78,79 These differences in host-agent interactions underscore the difficulty in establishing causation and the importance of confirmatory laboratory evidence to precisely identify the causal agent associated with infectious disease syndromes.

Once colonization or infection is established in a susceptible host, the agent may enter a silent or latent period during which there is no clinical or usual laboratory evidence of its presence. Thereafter, the host may manifest signs and symptoms of mild disease without disability, may have a rapid or slow progression of disease, or may progress to either temporary or chronic disability, or, ultimately, death. Alternatively, the patient may have a complete recovery and return to health without sequelae. In other instances, the entire process may be unapparent or subclinical without evidence of disability or disease. Subclinical cases may be recognized through laboratory testing of blood or other body fluids of the host. These tests may indicate evidence of abnormal cellular function (abnormal liver function tests), the presence of an immune response to infection (antibody to hepatitis B virus core antigen), the presence of antigens characteristic of the microorganism (positive test for hepatitis B virus surface antigen), or the presence of the microorganism itself.

The ability to diagnose an infection or disease is obviously easier in clinical cases and much easier in severe clinical cases wherein the typical signs and symptoms of the disease are apparent and routine tests are diagnostic of the agent. The ratio of clinical to subclinical infections varies widely by agent and is influenced by certain host factors, such as age, and immune status. Certain agents may be associated with a variety of different syndromes that depend on age and vaccination status of the host, previous infection with the agent, and agent-related mechanisms that remain unclear. Pertussis is often a severe disease in neonates but usually causes a three to six month mild respiratory infection in adults, and coxsackievirus B infections may appear as myocarditis 1 year and more prominently as meningoencephalitis the next. Respiratory syncytial virus infections may appear as bronchiolitis in infants and as a common cold syndrome in their older caregivers. Since the ability to diagnose an infection or disease caused by a specific pathogen depends partly on the degree to which typical symptoms and physical signs develop in patients, variation in the clinical manifestation of disease underscores the difficulty in establishing causation, the importance of clinical awareness of syndromic variations of certain infections, and the importance of confirmatory laboratory evidence to precisely identify the causal agent associated with syndromes of disease outbreaks. Evans provides a detailed and excellent review of the principles and issues in establishing causation in infection and disease.80,81,82

MECHANISM OF SPREAD

Transmission

For infection to take place, microorganisms must be transferred from a reservoir to an acceptable entry site on a susceptible host in sufficient numbers (the infecting dose) for multiplication to occur. The infecting dose of a microorganism may depend in varying degrees on infectivity, pathogenicity, or virulence of the microorganism itself. The entire transmission process constitutes the chain of infection. Within the healthcare setting, the reservoir of an agent may include patients themselves, HCP (eg, nares or fingernails), potable water, soap dispensers, hand lotions, mechanical ventilators, intravascular devices, infusates, multi-dose vials, or various other seemingly innocuous elements in the environment.

Direct transmission from another host (healthy or ill) or from an environmental reservoir or surface by direct contact or direct large-droplet spread of infectious secretions is the simplest route of agent spread. Examples of direct contact transmission routes include kissing (infectious mononucleosis), shaking hands (common cold [rhinovirus]), or other skin contact (eg, contamination of a wound with Staphylococcus spp. or Enterococcus spp. during trauma, surgical procedures, or dressing changes). Transmission of Neisseria meningitidis, group A Streptococcus, or the respiratory syncytial virus (an important cause of respiratory infection in young children worldwide) by large respiratory droplets that travel only a few feet is regarded as a special case of direct contact transmission.

Vertical transmission of infection from mother to fetus is another form of direct contact transmission that may occur through the placenta during pregnancy (eg, HIV, rubella virus, hepatitis B virus, or parvovirus) by direct contact of the infant with the birth canal during childbirth (group B streptococci) or via breast milk (HIV).

Indirect contact transmission may occur via the hands of people, contaminated inanimate objects (fomites), various work surfaces, food, biological fluids (eg, respiratory, salivary, gastrointestinal, or genital secretions, blood, urine, and stool), invasive or shared medical devices, or through arthropod or animal vectors. Indirect contact transmission is the most common mechanism of transfer of the microorganisms that cause HAIs and commonly occurs via the hands of HCPs, their clothing, or instruments like stethoscopes or thermometers. Rapid dissemination of agents, such as respiratory syncytial virus or the influenza virus may occur in day care centers through salivary contamination of shared toys and games. C difficile is an important cause of infectious diarrhea transmitted from patient to patient in acute care hospitals. Its transmission is abetted by its spore-forming ability to survive in the environment, and its selection and promotion in patients by the repeated and prolonged use of antimicrobials.83,84,85 Medical devices contaminated with bloodborne pathogens, including hepatitis B and C viruses and HIV, are sources of infection for both patients and HCPs in healthcare institutions. Some viruses can remain viable for extended periods under suitable conditions. For example, hepatitis B virus is relatively stable in the environment and remains viable in dried form for at least 7 days to 2 weeks on normal working surfaces

at room temperature. This property has led to hepatitis B virus transmission among dialysis patients through indirect contact via dialysis personnel or work surfaces in the dialysis unit.86,87,88,89,90,91 Examples of other sources of HAIs that occur through indirect contact include bacterial or viral contamination of musculoskeletal allograft tissues, intrinsic contamination of infusates or injectable medications, liquid soap dispensers, or contaminated medications prepared in the hospital pharmacy.92,93,94,95,96,97 The continuing presence of Pseudomonas spp. and other Gram-negative rods in potable water supplies acts as an important reservoir for these agents and a readily available source for hand transmission to patients, especially the severely ill.98,99,100,101,102

at room temperature. This property has led to hepatitis B virus transmission among dialysis patients through indirect contact via dialysis personnel or work surfaces in the dialysis unit.86,87,88,89,90,91 Examples of other sources of HAIs that occur through indirect contact include bacterial or viral contamination of musculoskeletal allograft tissues, intrinsic contamination of infusates or injectable medications, liquid soap dispensers, or contaminated medications prepared in the hospital pharmacy.92,93,94,95,96,97 The continuing presence of Pseudomonas spp. and other Gram-negative rods in potable water supplies acts as an important reservoir for these agents and a readily available source for hand transmission to patients, especially the severely ill.98,99,100,101,102

Airborne transmission is another mechanism of indirect transfer of pathogens. Microorganisms transmitted by this method include droplet nuclei (1-10 µm) that remain suspended in air for long periods, spores, and shed microorganisms. The airborne transfer of droplet nuclei is the principal route of transmission of M tuberculosis, varicella, and measles. The transmission of Legionella spp. through the air in droplet nuclei from cooling tower emissions, and from environmental water sites, such as air conditioning systems, central humidifiers, and respiratory humidification devices, is another important example of this type of spread.103,104,105,106,107,108 More recently, outbreaks of Mycobacterium chimaera were found to be secondary to contamination of exhaust air from heater-cooler devices used during cardiac surgery.109,110 The emergence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of M tuberculosis (ie, strains resistant to practically all second-line agents) has again highlighted the importance of airborne transmission and the fact that the underlying reason for XDR emergence stems from poor general tuberculosis control measures and the subsequent development of multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis.111,112,113

CDI, the most common cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea in the United States, can be acquired through the transmission of spores via hospital work surfaces and the hands of HCP.85,114,115 Fungal spores can be an important cause of HAIs. Spores of invasive fungi, such as Aspergillus spp., may be carried over long distances in hospitals to cause severe infections in immunosuppressed patients. The risk of spore contamination was highlighted by an outbreak of Curvularia lunata (a black fungus) among silicone breast implant recipients, who had undergone the breast augmentation procedures in an operating room that was erroneously maintained at negative pressure resulting in high spore counts in the operating room environment (operating rooms are supposed to be maintained at net positive pressures relative to adjacent areas).116 The surgeons had not implemented a closed system for inflating the breast prostheses with saline; instead, they had inflated the silicone prostheses using syringes filled with saline drawn up from a sterile bowl exposed to the ambient operating room environment. The end result was contamination of sterile saline in the open bowl with C lunata spores, which were then injected inadvertently into the breast prostheses.117 In some settings (eg, burn units), staphylococci have been thought to spread on skin squamous cells that have been shed from patients or HCP. The importance of this mode of transmission, however, is not thought to be of great significance in other care settings. More recent data suggest that S aureus is a common isolate in oropharyngeal cultures.118,119 Although the epidemiologic implications of this finding remain uncharacterized, the ramification for infection control in healthcare facilities would be enormous if indeed the chain of infection for S aureus includes oropharyngeal secretions or droplet nuclei.

Vector-borne transmission by arthropods or other insects is a form of indirect transmission and may be mechanical or biologic. In mechanical vector-borne transmission, the agent does not multiply or undergo physiologic changes in the vector; in biologic vector-borne transmission, the agent is modified within the host before being transmitted. Although the potential for microorganism carriage by arthropods or other insect vectors has been described,120,121 this type of transmission has not played any substantial role in the transmission of HAIs in the United States. In tropical countries with endemic dengue, yellow fever, or malaria, vector-borne transmission of infectious diseases is more important, requiring screening of patients or other interventions, and preventive measures not ordinarily required for patients in colder climates.

Reservoirs

Humans are the primary reservoir for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, HIV, hepatitis B and C viruses, and Shigella spp. Animals (zoonoses) harbor rabies virus, Yersinia pestis, Leptospira spp., nontyphi Salmonella, and Brucella spp. Environmental reservoirs include the soil (Histoplasma capsulatum, Clostridium tetani, and Bacillus anthracis) and water (Legionella spp., P aeruginosa, Serratia spp., and Acinetobacter spp). For some infections, the interaction between host, agent, and environment might include an extrinsic life cycle of the agent outside of the human host. The interplay of such factors can add significant layers of epidemiological complexity to properly understand the cause of an outbreak or in characterizing the chain of infection.

INCUBATION PERIOD AND COMMUNICABILITY

The incubation period is the time between exposure to an infectious agent and the first appearance of evidence of disease in a susceptible host. The incubation period of a pathogen usually is typical for that class of microorganisms and may be helpful in diagnosing unknown illness or making a decision regarding further diagnostic testing. The first portion of the incubation period after colonization and infection of a person is frequently a silent period, called the latent period. During this time, there is no obvious host response, and evidence of the presence of the infecting agent may not be measurable or discernible. Measurable early immune responses in the host may appear shortly before the first signs and symptoms of disease, marking the end of the latent period. Incubation periods for a microorganism vary by route of pathogen inoculation and the infecting dose. For example, brucellosis may be contracted through direct contact with blood or infected organic material, ingestion of raw, unpasteurized dairy products, or through airborne transmission in a laboratory or abattoir. The various modes of transmission for Brucella spp. results in an incubation period for brucellosis that is highly

variable, ranging from 5 days to several months. Incubation periods for other common microorganisms are as follows: 1-4 days for the rhinovirus (the common cold) or influenza virus,122 5-7 days for herpes simplex virus,123 7-14 days for polio virus,124 6-21 days for measles virus,122 10-21 days for varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox virus),125 20-50 days for hepatitis A virus126 and the rabies virus,127 and 80-100 days for hepatitis B virus.128

variable, ranging from 5 days to several months. Incubation periods for other common microorganisms are as follows: 1-4 days for the rhinovirus (the common cold) or influenza virus,122 5-7 days for herpes simplex virus,123 7-14 days for polio virus,124 6-21 days for measles virus,122 10-21 days for varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox virus),125 20-50 days for hepatitis A virus126 and the rabies virus,127 and 80-100 days for hepatitis B virus.128