© Springer International Publishing AG 2017

Doruk Erkan and Michael D. Lockshin (eds.)Antiphospholipid Syndrome10.1007/978-3-319-55442-6_1212. Prevention and Treatment of Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome

(1)

Department of Obstetrics, Hospital Universitario Pedro Ernesto, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

(2)

Obstetrics and Gynecology, Maternal-Fetal Medicine, University of Utah Health Care, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

(3)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

(4)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Keywords

Obstetric antiphospholipid syndromeFetal lossMiscarriageHeparinAspirinIntrauterine growth restrictionIntroduction

Initial excitement surrounding the treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) to improve pregnancy outcomes, particularly to avoid pregnancy loss, was understandable. In the mid-1980s there was no proven “treatment” for recurrent miscarriage or otherwise unexplained fetal death . Early case series included patients with lupus anticoagulant (LA) and involved treatment during pregnancy with glucocorticoids and low-dose aspirin (LDA). Heparin was used in hopes of improving placental blood flow. Both prednisone and heparin seemed to improve pregnancy outcomes in uncontrolled case series. A multicenter randomized trial found that heparin and LDA were as effective as glucocorticoid and LDA and were associated with a better safety/adverse event profile [1]. This trial, however, was limited in terms of small sample size and uncertainties regarding patient selection. By the early 1990s, the most commonly used treatment of pregnant patients with APS was established as heparin and LDA, and so it remains.

This chapter has two sections concerning pregnant aPL-positive patients : assessment and treatment. Treatment is discussed separately for two different populations: (a) those with recurrent early miscarriage; and (b) those with a history of thrombosis , mid-second or third trimester fetal death, or early delivery because of severe preeclampsia or placental insufficiency . (The term “obstetric APS” used in this text refers to both forms.)

Assessment of Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients with Pregnancy Morbidity

Given the relative infrequency of fetal death (loss of a fetus ≥10 weeks of gestation) relative to early pregnancy loss (miscarriage, before 10 weeks), proper assessment should document the gestational age of the pregnancy death (not, as is commonly done, the gestational age at diagnosis, when clinical symptoms or serendipitous diagnosis occur). Thus, an embryo that dies at eight menstrual weeks of gestation , but is first diagnosed at 11 weeks, is often wrongly considered to be a fetal death [2].

Several objective criteria can be used to confirm gestational age of a loss. Crown-rump length measured on ultrasound ≥3.0 cm documents 10-week gestational age. Other methods include having heard fetal heart tones with a handheld Doppler device at a specified time or assessment of fetal size directly after delivery or uterine evacuation [2].

The fetal death should be unexplained to qualify as an APS criterion . Other known causes of pregnancy loss should be excluded. This is not always done for a variety of reasons, including an assumption that an evaluation “will not bring my baby back”, fears or misconceptions about testing, avoidance of uncomfortable or unpleasant issues by the clinician, and financial concerns.

Considering early spontaneous abortion, chromosomal abnormality is the most frequent reason in patients with two or more miscarriages, a frequency similar to that found in patients with a single sporadic spontaneous abortion [3]. Investigation of chromosomal abnormalities in abortions is infrequently performed in clinical practice because of cost, accessibility of the test, and technical limitations. Another genetic cause of recurrent miscarriage is parental balanced translocations, detectable through analysis of parental karyotype [4].

Uterine malformations occur in up to 15% of women with recurrent pregnancy losses. Evaluation with three-dimensional ultrasound, hysterosalpingogram, diagnostic hysteroscopy, and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be considered if suspected. Although more related to second trimester losses, some authors advise that uterine cavity evaluation should be part of an evaluation. Uncontrolled endocrine abnormalities, such as diabetes and hypothyroidism, may also cause early abortion; treatment can improve gestational outcome [4].

Recent well-designed studies have questioned whether inherited thrombophilias, infections, and alloimmune factors, previously associated with recurrent miscarriages, are worth investigating. The current answer is no, because of lack of established association and/or effective treatment [4].

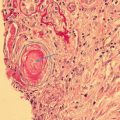

The optimal evaluation for potential causes of fetal death is uncertain. Considering cost, inconvenience, and potential yield, it is reasonable to focus on tests that have a high chance of providing useful information, on the most frequent conditions and on those, such as APS, with implications for subsequent pregnancies. Although many tests are recommended in the evaluation of stillbirth [5], the most consistently useful tests are perinatal autopsy, placental histology, and genetic testing (either karyotype or chromosomal microarray). Testing for aPL is helpful in cases in which fetal growth restriction, placental insufficiency, or severe preeclampsia has occurred. Other testing is best limited to cases in which clues from the clinical history or results of autopsy or other findings suggest specific diagnoses.

Determining a cause of death can be difficult, even after a complete diagnostic evaluation. There are many different causes of fetal death, and there may be uncertainties regarding a cause. There may be more than one cause; many potential etiologies may be risk factors rather than causes, since they often occur in live births, and some conditions, for instance, diabetes, may contribute to fetal death when severe but not when mild.

Over 60 classification systems have been developed to catalog potential causes of stillbirth. None is uniformly accepted worldwide. A major hurdle is a lack of a gold standard to validate the classification system. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN) , using rigorous definitions and the best available evidence to create a classification system named INCODE [6], conducted a multicenter case-control study of stillbirths and live births in the USA in five regions. In a cohort of over 500 stillbirths, INCODE identified a probable cause of death in 60.9% and a possible or probable cause in 76.2% [7].

The results of testing for antibodies to cardiolipin (aCL) and to β2GPI-glycoprotein-I (aβ2GPI) in the SCRN study underscore the importance of a thorough evaluation for fetal death. A higher proportion of women with stillbirth (excluding fetal anomalies) had positive tests for IgG aCL than did controls (5.0% vs 1.0%; OR 5.30; 95% CI 2.29–11.76) [8]. IgM aCL and IgG aβ2GPI were also associated with stillbirth. Although 56 women had positive tests for aPL, only 14% of these had APS as a probable cause based on INCODE [8]. Several cases with aPL had major genetic abnormalities.

The number of requirements for valid evaluation of pregnancy loss highlights a glaring oversight of many published trials: failure to meticulously characterize [2] and stratify subjects according to the gestational age of prior pregnancy losses, exclusion of other causes, and number of prior losses required (or allowed) for inclusion in the trial. Studies are difficult to compare because the definition of aPL positivity varies [9, 10], many reported subjects having indeterminate or low levels. In the majority of published trials, many subjects meet neither the 1999 [11] nor the 2006 [12] criteria for APS. Most published trials are plagued by small sample size, lack of blinding, and lack of a placebo control.

The associations between aPL and preeclampsia and placental insufficiency are addressed in Chap. 6. Two systematic reviews emphasize that the association between aPL and preeclampsia rests on the link to preeclampsia with severe features, typically in women who are delivered preterm [13, 14].

Although the review by do Prado et al. included 12 primary studies in a meta-analysis, confirming the strong association of aPL with severe preeclampsia (OR 11.15, 95% CI 2.66–46.75), only half of the studies specified criteria for severe preeclampsia.

The review by Abou-Nassar et al. included 28 studies. LA positivity was associated with preeclampsia in case-control (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.18–4.64) but not in cohort studies (OR 5.17, 95% CI 0.60–44.56) [14]; aCL was associated with preeclampsia in case-control studies (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.05–2.20) but not in cohort studies (OR 1.78, 95% CI 0.39–8.16); and, paradoxically, aβ2GPI was associated with preeclampsia in cohort studies (OR 19.14, 95% CI 6.34–57.77) but not in case-control studies. This review also evaluated preeclampsia and placental insufficiency, defined by late fetal loss, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or placental abruption and found an association of IUGR with LA in case-control studies (OR 4.65, 95% CI 1.18–4.64) and with aβ2GPI in cohort studies (OR 20.03, 95% CI 4.59–87.43) [14].

Both systematic reviews note that existing studies have high variability in their definitions of preeclampsia and placental insufficiency , often including women who deliver at term, and inclusion inconsistent with the revised Sapporo APS Classification Criteria [12]. Existing studies also include widely variable definitions of aPL positivity, including considering low thresholds of aPL, and not testing for all three aPL (LA, aCL, and aβ2GPI). Only a handful of studies report confirmatory testing of aPL at 12 or more weeks after initial test.

An abstract presented by Gibbins and colleagues during the 15th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies used strict cutoffs for aPL positivity (>40 GPL or MPL), tested all three aPL (LA, aCL, and aβ2GPI), and only considered a patient a case if she was delivered before 36 weeks. The investigators found an association between aPL and severe, preterm preeclampsia or placental insufficiency [15]. In this study, 10.5% of patients with preeclampsia or placental insufficiency tested positive for aPL, compared to 1.5% of controls (OR 7.59, 95% CI 1.63–35.42). Only 52.6% of women returned for repeat confirmatory testing.

Treatment of Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients with Pregnancy Morbidity

In many trials, it is difficult to determine what proportion of enrolled subjects had only pregnancy losses prior to 10 weeks of gestation versus fetal deaths at/beyond 10 weeks of gestation , a distinction required by the criteria for APS [12]. Subjects are more frequently diagnosed with APS because of recurrent early miscarriage than because of prior thrombosis, fetal death, or early delivery for severe preeclampsia or placental insufficiency. Among women with recurrent early miscarriage who also test positive for aPL, the frequency of history of thrombosis, stillbirth, or pregnancy complicated by severe preeclampsia is small. These characteristics, greater numbers, and lack of comorbid conditions make a population of recurrent early miscarriage patients more amenable to treatment trials. Also, women diagnosed with APS because of prior thrombosis, fetal death, or severe preeclampsia are difficult to enroll in trials that include a placebo arm [9]. Because women with prior pregnancy losses and women with preterm birth due to preeclampsia or placental insufficiency desperately seek a modifiable cause, heparin and LDA are commonly prescribed when a positive test for aPL is found, even though the patient does not meet clinical or laboratory criteria for APS.

Many experts note the marked trial heterogeneity caused by variable entry criteria [9, 16]. In one review of association between aPL and recurrent miscarriage, almost one third of 46 studies analyzed patients with first trimester losses together with patients with second and/or third trimester losses, and 15 studies did not mention the gestational age. This is problematic, as pathogenesis of abortion varies with duration of gestation and chromosomal abnormalities being more common in early losses [9].

Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome Based on Recurrent Early Miscarriages

The most frequently quoted treatment trials of obstetric APS date from the 1990s and early 2000s. They included primarily women with recurrent early miscarriage. Most of these trials involved treatment with a heparin, prednisone, LDA or a combination of these agents. Only one trial [17] was blinded and placebo controlled. Only 40 patients completed the study, and there were no differences between patients who received LDA and those receiving placebo. The live birth was 80% or better in both groups; all but two infants were delivered at term. At least three other trials [18–20], all published before 2000, included no-treatment arms. The number of subjects in each of these trials was, and outcomes without treatment were, good. Silver et al. [21] randomized patients to prednisone plus LDA or LDA alone. Not only was there no difference between the groups in the rates of live births, but there were no perinatal losses at all. Importantly, women who received prednisone had more premature deliveries.

Four trials that included women with APS diagnosed primarily because of recurrent early miscarriage compared heparin plus LDA to LDA alone [22–25]. In two trials, the proportion of successful pregnancies were higher in the unfractionated heparin (UFH) arm [22, 23]. The other two trials used low-molecular-weight-heparin (LMWH) and found no benefit with the use of LMWH [24, 25]. The live birth rates in the LDA-only patients were 70% and 75%.

Two recent trials also compared either UFH or LMWH to LDA alone. In one trial, investigators randomized 72 women with predominantly recurrent early miscarriage who had > 18 GPL IgG aCL [26]. Those randomized to heparin plus LDA had a higher rate of live birth (84.8%) than did those in the LDA only group (61.5%). Another trial randomized 141 women with two or more miscarriages and who had LA, aCL IgG > 15 U, and/or IgM > 25 U on two occasions [27]. Women randomized to the bemiparin (a LMWH) did not take LDA. The live birth rates were 86% in the bemiparin group and 72% in the LDA group; the difference was significant.

Notably, only one trial [27] studied more than 100 patients. Given what is known about pregnancy outcomes in placebo- or aspirin-treated groups, some may reasonably conclude that statistical proof for or against treatment remains in question. The EAGeR trial [28], which randomized otherwise healthy women (who were not known to have aPL) with one or two prior miscarriages, to preconception LDA or placebo, was powered to find a 10% absolute difference in live birth rates and enrolled 1278 subjects. The live birth rates were the same (82%) in each arm among women with pregnancy test and ultrasound-confirmed pregnancies.

Three other studies comparing UFH to LMWH (each paired with LDA) found no difference in pregnancy outcomes among women with predominantly recurrent early miscarriage [29–31]. Two trials of women with APS primarily diagnosed because of recurrent early miscarriage compared heparin plus LDA to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) [32, 33]. In both, the live birth rate was over 70% in the heparin plus LDA group and under 60% in the IVIG group, results that weigh against the use of IVIG in these patients.

In summary, a critical review of existing trials that enrolled women with APS diagnosed predominantly because of recurrent early miscarriage allows several contrasting conclusions. Marked trial heterogeneity, largely because of variable patient entry criteria, makes it difficult to compare results. Other interpretation problems include the definition and gestational age of a confirmed pregnancy, small sample sizes, and lack of blinding. The successful pregnancy rates in no-treatment or LDA-treated patients varies from less than 50% to well over 70%.

One can conclude that the recommendation of heparin plus LDA to improve pregnancy outcomes in this subset of APS patients is based on evidence that is conflicting at best and unacceptably weak at worst. The most recent American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist Practice Bulletin states that, for women with APS without a preceding thrombotic event, “expert consensus suggests that clinical surveillance or prophylactic heparin” may be used in the antepartum period and that “prophylactic doses of heparin and LDA during pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum should be considered” [34].

Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome Based on Fetal Loss or Early Delivery Due to Severe Preeclampsia or Placental Insufficiency

It is difficult to randomize women with obstetric APS to a placebo arm , especially those with history of fetal losses. Only a few trials state how many patients with APS have a history of mid-second or third trimester fetal death or early delivery because of severe preeclampsia or placental insufficiency , much less analyze them separately. Also, the role of fetal monitoring and its impact on perinatal outcome are sometimes poorly defined. Experts agree that women with a history of thrombosis cannot be randomized to a regimen without thromboprophylaxis .

Nonetheless, two trials deserve consideration. In a randomized trial [25] of heparin plus LDA versus LDA alone that included patients with both inherited thrombophilias and aPL, 25% of subjects had a history of fetal death after 14 weeks of gestation (women with prior thrombosis were excluded). Although there were no differences between treatment groups with regard to live births or fetal losses after 14 weeks, only half the subjects had aPL, and they were not separately analyzed. In another small trial [35] that randomized women with APS to receive heparin plus LDA or IVIG plus heparin plus LDA, over 85% of subjects had a history of prior fetal death . All enrollees had live births, but the preterm birth rate was higher in the IVIG group.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree