Given the known increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with both oral contraceptive (OC) use and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), it is important to address questions about the prevention and management of hormone-associated VTE. Specifically, the objectives of this article are as follows: (1) to provide suggested clinical management approaches for the primary and secondary prevention of VTE for women with thrombophilia; (2) to provide suggested clinical management approaches for the primary and secondary prevention of VTE in the perioperative period for women taking OC or HRT; and (3) to provide practical management approaches for frequently encountered clinical scenarios relating to duration of treatment for hormone-associated VTE.

Hormonal therapy is a common therapeutic agent used by women in the form of the oral contraceptive (OC) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). An estimated 100 million women use a typical OC consisting of an estrogen and a progestin component, which is also available as transdermal and vaginal ring formulations. Approximately 13 million women use a progestin-only contraceptive, which has comparable contraceptive efficacy as the combined estrogen-progestin formulations and is available in oral, intramuscular, intrauterine, and subdermal formulations. HRT, which can be defined as an estrogen with or without a progestin that is given in oral or transdermal forms, is an effective treatment for menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor flushing and mood instability, and is recommended for short-term (<2 year) use in such patients. Transdermal HRT is widely used in Europe, whereas its use in North America is infrequent. In addition to systemic HRT, topical hormone replacement is available as an estrogen cream, an estradiol-containing vaginal ring and an estradiol-containing vaginal tablet and is an effective treatment for menopause-related vaginal symptoms such as vulvar and vaginal atrophy.

In the past decade, observational studies and randomized controlled trials have established that HRT is associated with a two- to threefold increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A few clinical studies have compared the risk for VTE between oral and transdermal HRT, with an approximately twofold higher risk for VTE with transdermal HRT reported in 2 case-control studies. However, these studies were small, and a five- to sevenfold increased risk for VTE with transdermal HRT could not be excluded. In another, larger, case-control study, there was an increased risk for VTE in users of oral HRT (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.8–6.8), but no increased risk for VTE in users of transdermal HRT (HR = 0.9; 95% CI: 0.5–1.6). A possible explanation for the clinical and biochemical differences between oral and transdermal HRT may be that transdermal HRT bypasses first-pass hepatic metabolism that occurs with oral HRT.

In women who use OCs, the risk of VTE is approximately two- to fourfold higher than that among those who do not use OCs, as demonstrated in 43 case-control studies since 1967, 3 prospective cohort studies, and 1 randomized controlled trial. However, the estimated absolute risk of developing VTE remains low, increasing from 1 per 10,000 person-years, to 2 to 4 per 10,000 person-years during the time when the OC is used. Interestingly, several studies have shown that the absolute risk for VTE in women who use OCs and have a prothrombotic blood disorder, such as the factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene G20210A mutations, is higher than expected from the addition of these risks, thereby suggesting a possible enhancement in their individual effect on thrombosis risk.

Little is known about the risk of VTE associated with the use of topical (vaginal) hormone replacement, as there are no published studies that specifically address this question. Systemic absorption is minimal with topical estrogen, suggesting that the risk of VTE may not be increased among users of topical estrogen therapy compared with nonusers. In addition, studies of OC use show that the risk of VTE is approximately twice as high in users of OCs containing higher estrogen doses in comparison with users of OCs containing lower estrogen doses; thus, the very low doses of estrogen commonly used for the effective treatment of the vaginal symptoms of menopause (ie, 0.3 mg conjugated equine estrogen per day for estrogen cream, 5–10 μg estrogen released per day for estradiol-containing vaginal ring and 25 μg estrogen per day for estradiol-containing vaginal tablet) may not be associated with an increased risk of VTE. However, more research is needed before firm conclusions can be made regarding the safety of topical (vaginal) hormone replacement.

Given the known increased risk of VTE associated with both OC use and HRT use, it is important to address questions about the prevention and management of hormone-associated VTE. Specifically, the objectives of this article are as follows: (1) to provide suggested clinical management approaches for the primary and secondary prevention of VTE for women with thrombophilia; (2) to provide suggested clinical management approaches for the primary and secondary prevention of VTE in the perioperative period for women taking the OC or HRT; and (3) to provide practical management approaches for frequently encountered clinical scenarios relating to duration of treatment for hormone-associated VTE.

Is screening for thrombophilia indicated for women who will be starting hormone therapy?

In women with thrombophilia, use of either OCs or HRT is associated with an increased risk of VTE. Given this increased risk, it may be a reasonable strategy to screen for thrombophilia before starting hormone therapy. However, a universal screening program for thrombophilia in women who are planning to take or who are already receiving an OC may not be feasible to prevent fatal VTE. For example, Vandenbroucke and associates have inferred that 400,000 women would have to be screened for the factor V Leiden mutation to prevent one VTE-related death. These investigators used an estimated annual incidence of VTE among factor V Leiden carriers who use the OC of 28.5 per 10,000 woman years and assumed a case-fatality rate of 2%, thereby estimating an annual death rate of 5.7 per 100,000. Thus, universal genetic screening before starting hormone therapy does not appear to be justified. Instead, a more reasonable approach would involve selective screening in women for whom there is an increased clinical index of suspicion for thrombophilia, such as a personal history of VTE or family history of VTE in first-degree relatives, consisting of parents and siblings.

Should hormone therapy be started in women with thrombophilia?

Women Considering an OC

In women with asymptomatic thrombophilia who do not have a prior history of VTE, counseling should be provided on the risk of OC-associated VTE and on alternative forms of contraception with the aim that the patient will partake in the clinical decision-making process. This open discussion is warranted because the risk of OC-associated VTE will vary depending on the prothrombotic blood abnormality. Thus, in heterozygous carriers of the factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A mutations, the risk for VTE, although greatly increased relative to nonusers of the OC, should be weighed against potential health benefits of the OC. This can be better achieved if the absolute risk of VTE with OC use is considered in such patients, which is 28 to 50 cases per 10,000 woman-years of OC use. This risk may be considered acceptable for some women and unacceptably high for others. The risk should be weighed against the health and social consequences of unplanned pregnancy if the OC is not used. In healthy women, VTE is more frequent during pregnancy than during OC use, with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 1000 deliveries and a 1% to 2% case-fatality rate.

In women with a deficiency of antithrombin III or protein C, it is prudent to avoid OCs because of the reported absolute risk for VTE with OC use of 400 per 10,000 patient-years of OC use. The OC-related VTE risk in carriers of protein S deficiency is uncertain but is likely comparably increased to that with other deficiencies of endogenous anticoagulants.

Another management option for contraception in women with asymptomatic thrombophilia is a progestin-only contraceptive. These preparations may be associated with a lower risk for VTE compared with combined estrogen-progestin OCs, presumably because the estrogen component of the OC is considered to harbor the prothrombotic effects. However, there are no studies that have addressed the safety of progestin-only contraceptives in women with asymptomatic thrombophilia or a history of VTE.

In women with symptomatic thrombophilia, that is, with prior VTE that occurred in association with a prothrombotic blood abnormality, OC use should generally be avoided. If an OC is used, consideration should be given for patients to receive coadministered antithrombotic therapy. One option is to use warfarin, administered to achieve an international normalized ratio (INR) range of 2.0 to 3.0, in combination with the OC. The antithrombotic effects of warfarin are likely to neutralize any prothrombotic effects of the OC given that, in relative terms, OC therapy is a weak risk factor for VTE. However, this approach, although reasonable, has not been assessed in prospective clinical trials. An alternative management approach may be use of low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) therapy in combination with the OC, which has advantages over warfarin therapy of not requiring laboratory monitoring, but has disadvantages relating to greater costs and the potential for heparin-induced osteopenia with long-term use. As with combined OC-warfarin therapy, the efficacy and safety of this management strategy have not been evaluated in prospective clinical trials.

Women Considering HRT

In otherwise healthy patients who are asymptomatic carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation, the risk of a first episode of VTE is four- to fivefold higher than the risk in patients without this mutation. In women who are asymptomatic carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation and are receiving HRT, the risk for a first episode of VTE is 7- to 17-fold higher than in patients without the factor V Leiden mutation who are not receiving HRT. Based on these relative risk estimates, the absolute risk for VTE can be determined based on individual patient characteristics. For example, in a patient who is a heterozygous carrier of the factor V Leiden mutation who is commencing treatment with HRT, the annual risk for VTE is estimated at 0.7% to 1.5% per year. Thus, for every 65 to 130 patients treated with HRT, 1 patient will develop VTE per year.

Estimating the risk of VTE with HRT use in women with other prothrombotic blood abnormalities is problematic because of a lack of relevant data. Compared with carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation, the risk for VTE appears less in carriers of the prothrombin mutation, and one can estimate the annual risk for VTE at less than 0.7% per year. In patients with deficiencies of the endogenous anticoagulants, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin, there are no data to provide estimates of risk for VTE. However, such patients have a high lifetime risk of developing VTE, which is up to 50% by the fourth or fifth decade of life. Consequently, it is likely that exposure to HRT in such patients will be associated with a high absolute risk for VTE, irrespective of the additive effect of HRT on this risk. In patients with elevated factor VIII, factor IX, factor XI, or hyperhomocysteinemia, data are lacking to make inferences about risk for VTE, either in nonusers or users of HRT. Finally, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies, which includes the lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies, there is also a lack of data to make inferences about VTE risk. However, such patients also may be at high risk for a first episode of VTE, particularly in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, and can be considered similar to patients with deficiencies of endogenous anticoagulants.

Thus, the risk of a first VTE when starting HRT is likely to be high in patients with a deficiency of endogenous anticoagulants; moderate to high in patients with factor V Leiden or prothrombin mutations; and uncertain in patients with elevated factor VIII, factor IX, factor XI, or hyperhomocysteinemia.

The approach to women with symptomatic thrombophilia who are interested in HRT is similar to that taken for women considering an OC. Namely, HRT should generally be avoided in women with prior VTE. This includes women who are interested in transdermal HRT. Although transdermal HRT may be associated with a lower or, possibly, no increased risk for VTE compared with oral HRT, extrapolating this premise to women with previous VTE should be done with caution. In any case, if HRT is used, coadministered antithrombotic therapy with warfarin or LMWH may be used. As with coadministered antithrombotic and OC therapy, the safety and efficacy of this management strategy has not been formally evaluated with prospective clinical trials.

Should hormone therapy be started in women with thrombophilia?

Women Considering an OC

In women with asymptomatic thrombophilia who do not have a prior history of VTE, counseling should be provided on the risk of OC-associated VTE and on alternative forms of contraception with the aim that the patient will partake in the clinical decision-making process. This open discussion is warranted because the risk of OC-associated VTE will vary depending on the prothrombotic blood abnormality. Thus, in heterozygous carriers of the factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A mutations, the risk for VTE, although greatly increased relative to nonusers of the OC, should be weighed against potential health benefits of the OC. This can be better achieved if the absolute risk of VTE with OC use is considered in such patients, which is 28 to 50 cases per 10,000 woman-years of OC use. This risk may be considered acceptable for some women and unacceptably high for others. The risk should be weighed against the health and social consequences of unplanned pregnancy if the OC is not used. In healthy women, VTE is more frequent during pregnancy than during OC use, with an estimated incidence of 1 case per 1000 deliveries and a 1% to 2% case-fatality rate.

In women with a deficiency of antithrombin III or protein C, it is prudent to avoid OCs because of the reported absolute risk for VTE with OC use of 400 per 10,000 patient-years of OC use. The OC-related VTE risk in carriers of protein S deficiency is uncertain but is likely comparably increased to that with other deficiencies of endogenous anticoagulants.

Another management option for contraception in women with asymptomatic thrombophilia is a progestin-only contraceptive. These preparations may be associated with a lower risk for VTE compared with combined estrogen-progestin OCs, presumably because the estrogen component of the OC is considered to harbor the prothrombotic effects. However, there are no studies that have addressed the safety of progestin-only contraceptives in women with asymptomatic thrombophilia or a history of VTE.

In women with symptomatic thrombophilia, that is, with prior VTE that occurred in association with a prothrombotic blood abnormality, OC use should generally be avoided. If an OC is used, consideration should be given for patients to receive coadministered antithrombotic therapy. One option is to use warfarin, administered to achieve an international normalized ratio (INR) range of 2.0 to 3.0, in combination with the OC. The antithrombotic effects of warfarin are likely to neutralize any prothrombotic effects of the OC given that, in relative terms, OC therapy is a weak risk factor for VTE. However, this approach, although reasonable, has not been assessed in prospective clinical trials. An alternative management approach may be use of low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) therapy in combination with the OC, which has advantages over warfarin therapy of not requiring laboratory monitoring, but has disadvantages relating to greater costs and the potential for heparin-induced osteopenia with long-term use. As with combined OC-warfarin therapy, the efficacy and safety of this management strategy have not been evaluated in prospective clinical trials.

Women Considering HRT

In otherwise healthy patients who are asymptomatic carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation, the risk of a first episode of VTE is four- to fivefold higher than the risk in patients without this mutation. In women who are asymptomatic carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation and are receiving HRT, the risk for a first episode of VTE is 7- to 17-fold higher than in patients without the factor V Leiden mutation who are not receiving HRT. Based on these relative risk estimates, the absolute risk for VTE can be determined based on individual patient characteristics. For example, in a patient who is a heterozygous carrier of the factor V Leiden mutation who is commencing treatment with HRT, the annual risk for VTE is estimated at 0.7% to 1.5% per year. Thus, for every 65 to 130 patients treated with HRT, 1 patient will develop VTE per year.

Estimating the risk of VTE with HRT use in women with other prothrombotic blood abnormalities is problematic because of a lack of relevant data. Compared with carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation, the risk for VTE appears less in carriers of the prothrombin mutation, and one can estimate the annual risk for VTE at less than 0.7% per year. In patients with deficiencies of the endogenous anticoagulants, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin, there are no data to provide estimates of risk for VTE. However, such patients have a high lifetime risk of developing VTE, which is up to 50% by the fourth or fifth decade of life. Consequently, it is likely that exposure to HRT in such patients will be associated with a high absolute risk for VTE, irrespective of the additive effect of HRT on this risk. In patients with elevated factor VIII, factor IX, factor XI, or hyperhomocysteinemia, data are lacking to make inferences about risk for VTE, either in nonusers or users of HRT. Finally, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies, which includes the lupus anticoagulant or anticardiolipin antibodies, there is also a lack of data to make inferences about VTE risk. However, such patients also may be at high risk for a first episode of VTE, particularly in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, and can be considered similar to patients with deficiencies of endogenous anticoagulants.

Thus, the risk of a first VTE when starting HRT is likely to be high in patients with a deficiency of endogenous anticoagulants; moderate to high in patients with factor V Leiden or prothrombin mutations; and uncertain in patients with elevated factor VIII, factor IX, factor XI, or hyperhomocysteinemia.

The approach to women with symptomatic thrombophilia who are interested in HRT is similar to that taken for women considering an OC. Namely, HRT should generally be avoided in women with prior VTE. This includes women who are interested in transdermal HRT. Although transdermal HRT may be associated with a lower or, possibly, no increased risk for VTE compared with oral HRT, extrapolating this premise to women with previous VTE should be done with caution. In any case, if HRT is used, coadministered antithrombotic therapy with warfarin or LMWH may be used. As with coadministered antithrombotic and OC therapy, the safety and efficacy of this management strategy has not been formally evaluated with prospective clinical trials.

What is the perioperative management of women who are using hormonal therapy and who are undergoing elective surgery?

To date, there is no compelling evidence from studies of users of the OC or HRT who require elective surgery that hormonal therapy needs to be temporarily discontinued before and after surgery. Some experts suggest that there is the potential that perioperative use of an OC will further increase the risk for lower limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT) beyond that conferred by the surgical procedure and postoperative immobility. A prospective cohort study found a nonstatistically significant doubling of the risk of postoperative DVT in women who used an OC during the month of surgery compared with those who stopped their OC use more than 1 month before surgery. However, the absolute incidence of postoperative DVT in young women remains low and the OC is a relatively weak risk factor for DVT compared with the risk associated with surgery alone and any possible additive effect of the OC is unlikely to be important in terms of the overall DVT risk.

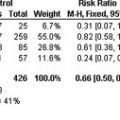

Among users of HRT, a similar uncertainty exists as to whether HRT should be temporarily interrupted in the perioperative period. Although there is the potential that perioperative use of HRT will further increase the risk for DVT beyond that conferred by the surgical procedure and postoperative immobility, HRT is a relatively weak risk factor for DVT compared with the risk associated with surgery. Thus, any possible additive effect of HRT may not be important in terms of the overall risk. In fact, it has been shown that there is a two- to threefold increased in risk for DVT in users of HRT compared with nonusers, whereas there is a 40- to 50-fold increased risk for DVT in patients undergoing elective major orthopedic surgery compared with those not undergoing surgery. Recent studies further suggest that perioperative use of HRT is not associated with a significant increase in the risk for postoperative VTE. In a case-control study of 318 postmenopausal women (108 cases, 210 controls) who underwent hip or knee replacement surgery, there was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative VTE in women who received perioperative HRT and women who did not receive perioperative HRT (17% vs 23%; odds ratio [OR] = 0.66; 95% CI: 0.35–1.18). In another case-control study that assessed 1168 women with DVT (256 cases, 912 controls), a subgroup of which had DVT occurring after exposure to a transient risk factor such as surgery or immobility, HRT use was not associated with an increased risk for DVT (OR = 1.17; 95% CI: 0.51–2.72).

Overall, in users of hormone therapy who require elective surgery, there is no compelling evidence that the hormone therapy needs to be discontinued in the perioperative period; however, appropriate methods of thromboprophylaxis should be considered in patients with other strong risk factors for VTE, such as prior VTE, or anticipated prolonged postoperative immobility. In these patients, appropriate management may include temporarily discontinuing the OC or HRT before and after surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree