Chapter 26 PREVENTION AND PROMOTION

INTRODUCTION

The aim of illness prevention and health promotion is to reduce the overall burden of mental health problems to improve the quality of life for older people. If there are family carers involved, which is often the case, these strategies will also decrease the likelihood of them also developing mental health problems. The needs of older people who are in higher acuity settings, such as residential aged care facilities (RACFs), must be considered by mental health workers. These older people experience greater rates of depression and dementia than their community-dwelling counterparts (O’Connor 2006, Rosewarne 1997). The presence of chronic physical conditions, such as cancer, cardiac problems, arthritis and stroke, increases the risk of mental health problems (Jorm 1995).

Awareness and understanding of positive mental health for older people may not rank highly on the list of priorities for a mental health worker surrounded by chronicity and working in a healthcare system focused on treating illness. However, the literature often states one of the reasons conditions such as depression, delirium and anxiety are so debilitating in the older age group is that they are underrecognised and undertreated in the first instance (Suominen et al 2004). Growth in this important area of healthcare has been stymied by negative attitudes of older people not having much longer to live (‘Why bother?’) and older people being seen as ‘unable’ or ‘too set in their ways’ to change their lifestyle (Cattan 2006). However, as much as other age groups, old age can be productive and fulfilling, and illness prevention and health promotion in this very dynamic area is easily influenced by innovations in drug treatments, therapeutic techniques, devices and technology.

The ageing of the population is now one of the driving forces for health promotion and illness prevention campaigns for older people. If the current prevalence rates of mental health problems affecting older people remain the same, this rate will increase proportionately as the number of older people increases. For example, in 2006, there were approximately 3 million (13%) older people in Australia and, therefore, 9.5% or 285,000 of these people had at least one long-term mental health or behavioural problem. However in 2056, with the impact of population ageing, there will be 9,840,000 (24%) people over the age of 65 years and, if 9.5% have a mental health problem, this equates to 934,800 in actual numbers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007).

A MODEL OF MENTAL HEALTH INTERVENTION

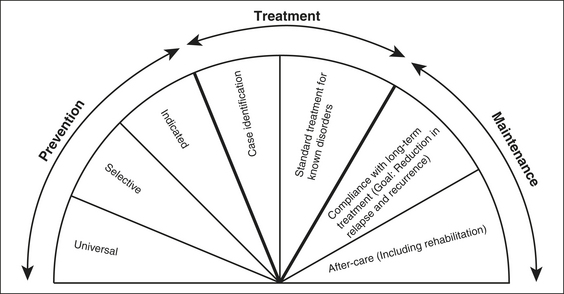

Conceptualisation of how to approach mental illness prevention and mental health promotion within mental healthcare is captured in Figure 26.1 (Mrazek & Haggerty 1994). This spectrum identifies the key components of promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment and continuing care. The best mental health outcomes will be achievable if effort is directed in all these areas. Sometimes, the boundaries between the different areas are not as distinct as this representation. In the practice setting, interventions may cross these boundaries, as well as combining a number of the components. Mental health promotion is defined as ‘any action taken to maximise mental health and wellbeing among populations and individuals’ (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 2000b, p 29), and it is relevant across the whole spectrum of interventions. This means that health promotion is targeted at people when they are well, if they are at risk and when they are unwell. The aim of mental health promotion is to optimise the mental health and wellbeing of communities and therefore the individuals who are part of the community (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 2000b).

Figure 26.1 The spectrum of interventions for mental health problems

Source: Mrazek and Haggerty (1994). Reprinted with permission from the National Academies Press. ©Copyright 1994 National Academy of Sciences.

Illness prevention is defined as ‘interventions that occur before the initial onset of a disorder’ to prevent the development of a disorder (Mrazek & Haggerty 1994, p 23). The aim of prevention is to reduce the risk factors for mental health problems and enhance the protective factors of mental health. Although illness prevention and health promotion have clearly different aims, the interventions and outcomes are often very similar. For instance, a mental health promotion activity may very well reduce the incidence of a mental health problem. Within Figure 26.1, there are three different types of prevention interventions. The first is universal, which targets the general population and includes programs that promote a healthy mind. The second type, selective, is for subgroups or individuals who have a higher than average rate of developing a mental health problem. A bereavement support group is an example of a selective intervention. The final type, indicated, is directed at individuals who are high risk and may have early signs of a mental health problem. An indicated intervention could be a behaviour management program for carers of an older person with dementia (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 2000b).

PREVENTION CONCEPTS

The public health approach is a common and appropriate way of classifying preventive strategies (Jenkins 1992). ‘Primary’ prevention involves finding the source of the mental health problem or stopping it before it occurs, and therefore reducing its incidence. Primary prevention targets people when they are in good health and particularly if they are at risk of developing the disease at a later stage of their life. Health promotion strategies that aim to improve health, rather than prevent disease, are well situated in primary prevention.

Primary prevention

The causal factors of many mental health problems are unknown, despite a considerable amount of research being undertaken (e.g. in Alzheimer’s disease) (Jorm 2000). On the other hand, primary prevention can be actioned for organic brain disorders caused by poisoning (including medication reactions), infections, genetic diseases, nutritional deficiencies, injuries and systemic disorders. There have also been reasonable efforts to identify, reduce or modify risk factors for mental health problems and suicide (Suominen et al 2004).

Stress often precipitates or exacerbates a mental health problem (Norman & Malla 1993, Paykel 1994). Stressors older people have to deal with usually come about via the significant losses they endure. Some changes are positive (e.g. more leisure time for family and friends, or travel). However, negative stressful experiences through changes regarding loss such as functional decline, death of a partner and significant others, and changes in roles, financial or living status, can be very significant for the older person. Although the actual losses cannot be prevented, functional decline and quality of life may be prevented or improved (Bartels & Pratt 2009). The use of assistive technologies, bereavement counselling for loss of a partner and friends through death, and support programs for other ageing issues, all help in managing the associated stress caused by loss (White et al 2002).

These preventive strategies can be delivered on an individual or group basis. Group-based activities are helpful in reducing stress, distress, social isolation and loneliness, and increasing resilience, self-esteem and social networks (Cattan et al 2005). There have been numerous programs developed and they follow the general themes of (Cattan et al 2005, Cole 2008, Hammond 2004, Pusey & Richards 2001, Wheeler et al 1998):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree