Prevention

If a patient asks a medical practitioner for help, the doctor does the best he can. He is not responsible for defects in medical knowledge. If, however, the practitioner initiates screening procedures, he is in a very different situation. He should have conclusive evidence that screening can alter the natural history of disease in a significant proportion of those screened.

—Archie Cochrane and Walter Holland 1971

KEY WORDS

Preventive care

Immunizations

Screening

Behavioral counseling

Chemoprevention

Primary prevention

Secondary prevention

Tertiary prevention

Surveillance

Prevalence screen

Incidence screen

Lead-time bias

Length-time bias

Compliance bias

Placebo adherence

Interval cancer

Detection Method

Incidence method

False-positive screening test result

Labeling effect

Overdiagnosis

Predisease

Incidentaloma

Quality adjusted life year (QALY)

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Most doctors are attracted to medicine because they look forward to curing disease. But all things considered, most people would prefer never to contract a disease in the first place—or, if they cannot avoid an illness, they prefer that it be caught early and stamped out before it causes them any harm. To accomplish this, people without specific complaints undergo interventions to identify and modify risk factors to avoid the onset of disease or to find disease early in its course so that early treatment prevents illness. When these interventions take place in clinical practice, the activity is referred to as preventive care.

Preventive care constitutes a large portion of clinical practice (1). Physicians should understand its conceptual basis and content. They should be prepared to answer questions from patients such as, “How much exercise do I need, Doctor?” or “I heard that a study showed antioxidants were not helpful in preventing heart disease. What do you think?” or “There was a newspaper ad for a calcium scan. Do you think I should get one?”

Much of the scientific approach to prevention in clinical medicine has already been covered in this book, particularly the principles underlying risk, the use of diagnostic tests, disease prognosis, and effectiveness of interventions. This chapter expands on those principles and strategies as they specifically relate to prevention.

PREVENTIVE ACTIVITIES IN CLINICAL SETTINGS

In the clinical setting, preventive care activities often can be incorporated into the ongoing care of patients, such as when a doctor checks the blood pressure of a patient complaining of a sore throat or orders pneumococcal vaccination in an older person after dealing with a skin rash. At other times, a special visit just for preventive care is scheduled; thus the terms annual physical, periodic checkup, or preventive health examination.

Types of Clinical Prevention

There are four major types of clinical preventive care: immunizations, screening, behavioral counseling

(sometimes referred to as lifestyle changes), and chemoprevention. All four apply throughout the life span.

(sometimes referred to as lifestyle changes), and chemoprevention. All four apply throughout the life span.

Immunization

Childhood immunizations to prevent 15 different diseases largely determine visit schedules to the pediatrician in the early months of life. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations of adolescent girls has recently been added for prevention of cervical cancer. Adult immunizations include diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) boosters and well as vaccinations to prevent influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia, and hepatitis A and B.

Screening

Screening is the identification of asymptomatic disease or risk factors. Screening tests start in the prenatal period (such as testing for Down syndrome in the fetuses of older pregnant women) and continue throughout life (e.g., when inquiring about hearing in the elderly). The latter half of this chapter discusses scientific principles of screening.

Behavioral Counseling (Lifestyle Changes)

Clinicians can give effective behavioral counseling to motivate lifestyle changes. Clinicians counsel patients to stop smoking, eat a prudent diet, drink alcohol moderately, exercise, and engage in safe sexual practices. It is important to have evidence that (i) behavior change decreases the risk for the condition of interest, and (ii) counseling leads to behavior change before spending time and effort on this approach to prevention (see Levels of Prevention later in the chapter).

Chemoprevention

Chemoprevention is the use of drugs to prevent disease. It is used to prevent disease early in life (e.g., folate during pregnancy to prevent neural tube defects and ocular antibiotic prophylaxis in all newborns to prevent gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum) but is also common in adults (e.g., low-dose aspirin prophylaxis for myocardial infarction, and statin treatment for hypercholesterolemia).

LEVELS OF PREVENTION

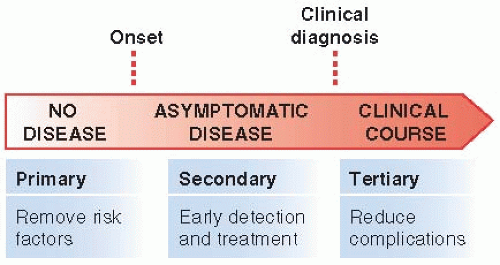

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary defines prevention as “the act of preventing or hindering” and “the act or practice of keeping something from happening” (2). With these definitions in mind, almost all activities in medicine could be defined as prevention. After all, clinicians’ efforts are aimed at preventing the untimely occurrences of the 5 Ds: death, disease, disability, discomfort, and dissatisfaction (discussed in Chapter 1). However, in clinical medicine, the definition of prevention has traditionally been restricted to interventions in people who are not known to have the particular condition of interest. Three levels of prevention have been defined: primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (Fig. 10.1).

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention keeps disease from occurring at all by removing its causes. The most common clinical primary care preventive activities involve immunizations to prevent communicable diseases, drugs, and behavioral counseling. Recently, prophylactic surgery has become more common, with bariatric surgery to prevent complications of obesity, and ovariectomy and mastectomy to prevent ovarian and breast cancer in women with certain genetic mutations.

Primary prevention has eliminated many infectious diseases from childhood. In American men, primary prevention has prevented many deaths from two major killers: lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. Lung cancer mortality in men decreased by 25% from 1991 to 2007, with an estimated 250,000 deaths prevented (3). This decrease followed smoking cessation trends among adults, without organized screening and without much improvement in survival after treatment for lung cancer. Heart disease mortality rates in men have decreased by half over the past several decades (4) not only because medical care has improved, but also because of primary prevention efforts such as smoking cessation and use of antihypertensive and statin medications. Primary prevention is now possible for cervical, hepatocellular, skin and breast cancer, bone fractures, and alcoholism.

A special attribute of primary prevention involving efforts to help patients adopt healthy lifestyles is that a single intervention may prevent multiple diseases. Smoking cessation decreases not only lung cancer but also many other pulmonary diseases, other cancers, and, most of all, cardiovascular disease. Maintaining an appropriate weight prevents diabetes and osteoarthritis, as well as cardiovascular disease and some cancers.

Primary prevention at the community level can also be effective. Examples include immunization requirements for students, no-smoking regulations in public buildings, chlorination and fluoridation of the water supply, and laws mandating seatbelt use in automobiles and helmet use on motorcycles and bicycles. Certain primary prevention activities occur in specific occupational settings (use of earplugs or dust masks), in schools (immunizations), or in specialized health care settings (use of tests to detect hepatitis B and C or HIV in blood banks).

For some problems, such as injuries from automobile accidents, community prevention works best. For others, such as prophylaxis in newborns to prevent gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum, clinical settings work best. For still others, clinical efforts can complement community-wide activities. In smoking prevention efforts, clinicians help individual patients stop smoking and public education, regulations, and taxes prevent teenagers from starting to smoke.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention detects early disease when it is asymptomatic and when treatment can stop it from progressing. Secondary prevention is a two-step process, involving a screening test and follow-up diagnosis and treatment for those with the condition of interest. Testing asymptomatic patients for HIV and routine Pap smears are examples. Most secondary prevention is done in clinical settings.

As indicated earlier, screening is the identification of an unrecognized disease or risk factor by history taking (e.g., asking if the patient smokes), physical examination (e.g., a blood pressure measurement), laboratory test (e.g., checking for proteinuria in a diabetic), or other procedure (e.g., a bone mineral density examination) that can be applied reasonably rapidly to asymptomatic people. Screening tests sort out apparently well persons (for the condition of interest) who have an increased likelihood of disease or a risk factor for a disease from people who have a low likelihood. Screening tests are part of all secondary and some primary and tertiary preventive activities.

A screening test is usually not intended to be diagnostic. If the clinician and/or patient are not committed to further investigation of abnormal results and treatment, if necessary, the screening test should not be performed at all.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention describes clinical activities that prevent deterioration or reduce complications after a disease has declared itself. An example is the use of beta-blocking drugs to decrease the risk of death in patients who have recovered from myocardial infarction. Tertiary prevention is really just another term for treatment, but treatment focused on health effects occurring not so much in hours and days but months and years. For example, in diabetic patients, good treatment requires not just control of blood glucose. Searches for and successful treatment of other cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and smoking) help prevent cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients as much, and even more, than good control of blood glucose. In addition, diabetic patients need regular ophthalmologic examinations for detecting early diabetic retinopathy, routine foot care, and monitoring for urinary protein to guide use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors to prevent renal failure. All these preventive activities are tertiary in the sense that they prevent and reduce complications of a disease that is already present.

Confusion about Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention

Over the years, as more and more of clinical practice has involved prevention, the distinctions among primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention have become blurred. Historically, primary prevention was thought of as primarily vaccinations for infectious disease and counseling for healthy lifestyle behaviors, but primary prevention now includes prescribing antihypertensive medication and statins to prevent cardiovascular diseases, and performing prophylactic surgery to prevent ovarian cancer in women with certain genetic abnormalities. Increasingly, risk factors are treated as if they are diseases, even at a time when they have not caused any of the 5 Ds. This is true for a growing number of health risks, for example, low bone mineral density, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and certain genetic abnormalities. Treating risk factors as disease broadens the definition of secondary prevention into the domain of traditional primary prevention.

In some disciplines, such as cardiology, the term secondary prevention is used when discussing tertiary prevention. “A new era of secondary prevention” was

declared when treating patients with acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina) with a combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies to prevent cardiovascular death (5). Similarly, “secondary prevention” of stroke is used to describe interventions to prevent stroke in patients with transient ischemia attacks.

declared when treating patients with acute coronary syndrome (myocardial infarction or unstable angina) with a combination of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies to prevent cardiovascular death (5). Similarly, “secondary prevention” of stroke is used to describe interventions to prevent stroke in patients with transient ischemia attacks.

Tests used for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, as well as for diagnosis, are often identical, another reason for confusing the levels of prevention (and confusing prevention with diagnosis). Colonoscopy may be used to find a cancer in a patient with blood in his stool (diagnosis); to find an early asymptomatic colon cancer (secondary prevention); remove an adenomatous polyp, which is a risk factor for colon cancer (primary prevention); or to check for cancer recurrence in a patient treated for colon cancer (a tertiary preventive activity referred to as surveillance).

Regardless of the terms used, an underlying reason to differentiate levels among preventive activities is that there is a spectrum of probabilities of disease and adverse health effects from the condition(s) being sought and treated during preventive activities, as well as different probabilities of adverse health effects from interventions that are used for prevention at the various levels. The underlying risk of certain health problems is usually much higher in diseased than healthy people. For example, the risk of cardiovascular disease in diabetics is much greater than in asymptomatic non-diabetics. Identical tests perform differently depending on the level of prevention. Furthermore, the trade-offs between effectiveness and harms can be quite different for patients in different parts of the spectrum. False-positive test results and overdiagnosis (both discussed later in this chapter) among people without the disease being sought are important issues in secondary prevention, but they are less important in treatment of patients already known to have the disease in question. The terms primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention are ways to consider these differences conceptually.

SCIENTIFIC APPROACH TO CLINICAL PREVENTION

When considering what preventive activities to perform, the clinician must first decide with the patient which medical problems or diseases they should try to prevent. This statement is so clear and obvious that it would seem unnecessary to mention, but the fact is that many preventive procedures, especially screening tests, are performed without a clear understanding of what is being sought or prevented. For instance, physicians performing routine checkups on their patients may order a urinalysis. However, a urinalysis might be used to search for any number of medical problems, including diabetes, asymptomatic urinary tract infections, renal cancer, or renal failure. It is necessary to decide which, if any, of these conditions is worth screening for before undertaking the test. One of the most important scientific advances in clinical prevention has been the development of methods for deciding whether a proposed preventive activity should be undertaken (6). The remainder of this chapter describes these methods and concepts.

Three criteria are important when judging whether a condition should be included in preventive care (Table 10.1):

The burden of suffering caused by the condition.

The effectiveness, safety, and cost of the preventive intervention or treatment.

The performance of the screening test.

Table 10.1 Criteria for Deciding Whether a Medical Condition Should Be Included in Preventive Care | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BURDEN OF SUFFERING

Only conditions posing threats to life or health (the 5 Ds in Chapter 1) should be included in preventive care. The burden of suffering of a medical condition is determined primarily by (i) how much suffering (in terms of the 5 Ds) it causes those afflicted with the condition, and (ii) its frequency.

How does one measure suffering? Most often, it is measured by mortality rates and frequency of hospitalizations and amount of health care utilization caused by the condition. Information about how much disability, pain, nausea, or dissatisfaction a given disease causes is much less available.

The frequency of a condition is also important in deciding about prevention. A disease may cause great suffering for individuals who are unfortunate enough to get it, but it may occur too rarely—especially in the individual’s particular age group—for screening to be considered. Breast cancer is an example. Although it can occur in much younger women, most breast cancers occur in women older than 50 years of age. For 20-year-old women, annual breast cancer incidence is 1.6 in 100,000 (about one-fifth the rate for men in their later 70s) (7). Although breast cancer should be sought in preventive care for older women, it is too uncommon in average 20-year-old women and 70-year-old men for screening. Screening for very rare diseases means not only that, at most, very few people will benefit, but screening also results in false-positive tests in some people who are subject to complications from further diagnostic evaluation.

The incidence of what is to be prevented is especially important in primary and secondary prevention because, regardless of the disease, the risk is low for most individuals. Stratifying populations according to risk and targeting the higher-risk groups can help overcome this problem, a practice frequently done by concentrating specific preventive activities on certain age groups.

EFFECTIVENESS OF TREATMENT

As pointed out in Chapter 9, randomized controlled trials are the strongest scientific evidence for establishing the effectiveness of treatments. It is usual practice to meet this standard for tertiary prevention (treatments). On the other hand, to conduct randomized trials when evaluating primary or secondary prevention requires very large studies on thousands, often tens of thousands, of patients, carried out over many years, sometimes decades, because the outcome of interest is rare and often takes years to occur. The task is daunting; all the difficulties of randomized controlled trials laid out in Chapter 9 on Treatment are magnified many-fold.

Other challenges in evaluating treatments in prevention are outlined in the following text for each level of prevention.

Treatment in Primary Prevention

Whatever the primary intervention (immunizations, drugs, behavioral counseling, or prophylactic surgery), it should be efficacious (able to produce a beneficial result in ideal situations) and effective (able to produce a beneficial net result under usual conditions, taking into account patient compliance). Because interventions for primary prevention are usually given to large numbers of healthy people, they also must be very safe.

Randomized Trials

Virtually all recommended immunizations are backed by evidence from randomized trials, sometimes relatively quickly when the outcomes occur within weeks or months, as in childhood infections. Because pharmaceuticals are regulated, primary and secondary preventive activities involving drugs (e.g., treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia in adults) also usually have been evaluated by randomized trials. Randomized trials are less common when the proposed prevention is not regulated, as is true with vitamins, minerals, and food supplements, or when the intervention is behavioral counseling.

Observational Studies

Observational studies can help clarify the effectiveness of primary prevention when randomization is not possible.

Example

Randomized trials have found hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccines highly effective in preventing hepatitis B. Because HBV is a strong risk factor for hepatocellular cancer, one of the most common and deadly cancers globally, it was thought that HBV vaccination would be useful in preventing liver cancer. However, the usual interval between HBV infection and development of hepatocellular cancer is two to three decades. It would not be ethical to withhold from a control group a highly effective intervention against an infectious disease to

determine if decades later it also was effective against cancer. A study was done in Taiwan, where nationwide HBV vaccination was begun in 1984. The rates of hepatocellular cancer rates were compared among people who were immunized at birth between 1984 and 2004 to those born between 1979 and 1984 when no vaccination program existed. (The comparison was made possible by thorough national health databases on the island.) Hepatocellular cancer incidence decreased almost 70% among young people in the 20 years after the introduction of HBV vaccination (8).

determine if decades later it also was effective against cancer. A study was done in Taiwan, where nationwide HBV vaccination was begun in 1984. The rates of hepatocellular cancer rates were compared among people who were immunized at birth between 1984 and 2004 to those born between 1979 and 1984 when no vaccination program existed. (The comparison was made possible by thorough national health databases on the island.) Hepatocellular cancer incidence decreased almost 70% among young people in the 20 years after the introduction of HBV vaccination (8).

As pointed out in Chapter 5, observational studies are vulnerable to bias. The conclusion that HBV vaccine prevents hepatocellular carcinoma is reasonable from a biologic perspective and from the dramatic result. It will be on even firmer ground if studies of other populations who undergo vaccination confirm the results from the Taiwan study. Building the case for causation in the absence of randomized trials is covered in Chapter 12.

Safety

With immunizations, the occurrence of adverse effects may be so rare that randomized trials would be unlikely to uncover them. One way to study this question is to track illnesses in large datasets of millions of patients and to compare the frequency of an adverse effect linked temporally to the vaccination among groups at different time periods.

Example

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare, serious immune-mediated neurological disorder characterized by ascending paralysis that can temporarily involve respiratory muscles so that intubation and ventilator support are required. A vaccine developed against swine flu in the 1970s was associated with an unexpected sharp rise in the number of cases of GBS and contributed to suspension of the vaccination program. In 2009, a vaccine was developed to protect against a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus of swine origin, and a method was needed to track GBS incidence. One way this was done was to utilize a surveillance system of the electronic health databases of more than 9 million persons. Comparing the incidence of GBS occurring up to 6 weeks after vaccination to that of later (background) GBS occurrence in the same group of vaccinated individuals, the attributable risk of the 2009 vaccine was estimated to be an additional five cases of GBS per million vaccinations. Although GBS incidence increased after vaccination, the effect in 2009 was about half that seen in the 1970s (9). The very low estimated attributable risk in 2009 is reassuring. If rare events, occurring in only a few people per million are to be detected in near real time, population-based surveillance systems are required. Even so, associations found in surveillance systems are weak evidence for a causal relationship because they are observational in nature and electronic databases often do not have information on all important possible confounding variables.

Counseling

U.S. laws do not require rigorous evidence of effectiveness of behavioral counseling methods. Nevertheless, clinicians should require scientific evidence before incorporating routine counseling into preventive care; counseling that does not work wastes time, costs money, and may harm patients. Research has demonstrated that certain counseling methods can help patients change some health behaviors. Smoking cessation efforts have led the way with many randomized trials evaluating different approaches.

Example

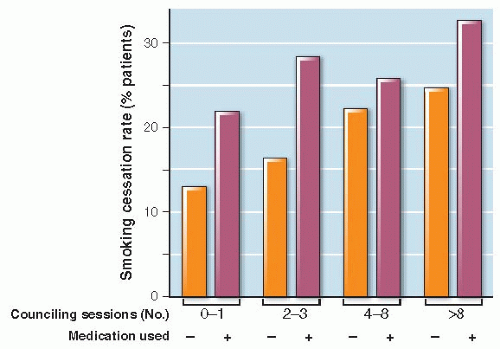

Smoking kills approximately 450,000 Americans each year. But, what is the evidence that advising patients to quit smoking gets them to stop? Are some approaches better than others? These questions were addressed by a panel that reviewed all studies done on smoking cessation, focusing on randomized trials (10). They found 43 trials that assessed amounts of counseling contact and found a dose-response—the more contact time the better the abstinence rate (Fig. 10.2). In addition, the panel found that randomized trials demonstrated that pharmacotherapy with bupropion (a centrally acting drug that decreases craving), varenicline (a nicotine

receptor agonist), nicotine gum, nasal spray, or patches were effective. Combining counseling and medication (evaluated in 18 trials) increased the smoking cessation rate still further. On the other hand, there was no effect of anxiolytics, beta-blockers, or acupuncture.

receptor agonist), nicotine gum, nasal spray, or patches were effective. Combining counseling and medication (evaluated in 18 trials) increased the smoking cessation rate still further. On the other hand, there was no effect of anxiolytics, beta-blockers, or acupuncture.

Treatment in Secondary Prevention

Treatments in secondary prevention are generally the same as treatments for curative medicine. Like interventions for symptomatic disease, they should be both efficacious and effective. Unlike usual interventions for disease, however, it typically takes years to establish that a secondary preventive intervention is effective, and it requires large numbers of people to be studied. For example, early treatment after colorectal cancer screening can decrease colorectal cancer deaths by approximately one-third, but to show this effect, a study of 45,000 people with 13 years of follow-up was required (11).

A unique requirement for treatment in secondary prevention is that treatment of early, asymptomatic disease must be superior to treatment of the disease when it would have been diagnosed in the usual course of events, when a patient seeks medical care for symptoms. If outcome in the two situations is the same, screening does not add value.

Example

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Why, then, did no major professional medical group recommend screening for lung cancer throughout the first decade of the 21st century? Several randomized trials begun in the 1970s and 1980s found screening was not protective. In one study of the use of chest x-rays and sputum cytology to screen for lung cancer, male cigarette smokers who were screened every 4 months and treated promptly when cancer was found did no better than those not offered screening and treated only when they presented with symptoms. Twenty years later, death rates from lung cancer were similar in the two groups—4.4 per 1,000 person-years in the screened men versus 3.9 per 1,000 persons-years in men not offered screening (12). However, in 2011, a randomized controlled trial of low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening reported a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality after a median of 6.5 years (13). This trial convincingly demonstrated for the first time that treatment of asymptomatic lung cancer found on screening decreased mortality.

Treatment in Tertiary Prevention

All new pharmaceutical treatments in the United States are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which almost always requires evidence of efficacy from randomized clinical trials. It is easy to assume, therefore, that tertiary preventive treatments have been carefully evaluated. However, after a drug has been approved, it may be used for new, unevaluated, indications. Patients with some diseases are at increased risk for other diseases; thus, some drugs are used not only to treat the condition for which they are approved but also to prevent other diseases for which patients are at increased risk. The distinction between proven therapeutic effects of a medicine for a given disease and its effect in preventing other diseases is a subtle challenge facing clinicians when considering tertiary preventive interventions that have not been evaluated for that purpose. Sometimes, careful evaluations have led to surprising results.

Example

In Chapter 9, we presented an example of a study of treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes. It showed the surprising result that tight control of blood sugar (bringing the level down to normal range) did not prevent cardiovascular disease and mortality any better than looser control. The diabetic medications used in this and other studies finding similar results were approved after randomized controlled studies. However, the outcomes leading to approval of the drugs was not prevention of long-term cardiovascular disease (tertiary prevention) among diabetics, but rather the effect of the medications on blood sugar levels. The assumption was made that these medications would also decrease cardiovascular disease because observational studies had shown blood sugar levels correlated with cardiovascular disease risk. Putting this assumption to the test in rigorous randomized trials produced surprising and important results. As a result, tertiary prevention in diabetes has shifted toward including aggressive treatment of other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. With such an approach, a randomized trial showed that cardiovascular disease and death in diabetics were reduced about 50% over a 13-year period, compared to a group receiving conventional therapy aimed at controlling blood sugar levels (14).

METHODOLOGIC ISSUES IN EVALUATING SCREENING PROGRAMS

Several problems arise in the evaluation of screening programs, some of which can make it appear that early treatment is effective after screening when it is not. These issues include the difference between prevalence and incidence screens and three biases that can occur in screening studies: lead-time, length-time, and compliance biases.

Prevalence and Incidence Screens

The yield of screening decreases as screening is repeated over time. Figure 10.3 demonstrates why this is so. The first time that screening is carried out—the prevalence screen—cases of the medical condition will have been present for varying lengths of time. During the second round of screening, most cases found will have had their onset between the first and second screening. (A few will have been missed by the first screen.) Therefore, the second (and subsequent) screenings are called incidence screens. Thus, when a group of people are periodically rescreened, the number of cases of disease

in the group drops after the prevalence screen. This means that the positive predictive value for test results will decrease after the first round of screening.

in the group drops after the prevalence screen. This means that the positive predictive value for test results will decrease after the first round of screening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree