General Principles

Today’s older people are increasingly interested in promoting healthy aging. The terms “health promotion” and “prevention” are used almost interchangeably. Prevention runs a gamut. For the most part, we think of prevention in terms of warding off disease or delaying its onset, but prevention can also involve simply avoiding bad events or complications of care. As noted in Chapter 4, in the context of chronic disease management, proactive primary care can be seen as a form of prevention (tertiary prevention, as defined later). Prevention is typically targeted at specific diseases or conditions, but some authors caution against such a single-disease approach to prevention among older persons, arguing that competitive risks will simply raise the rates for other diseases (Mangin, Sweeney, and Heath, 2007). Likewise, some preventive efforts, like stopping smoking and exercising, can affect many diseases.

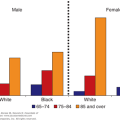

Ageism may lead people to discount the value of prevention in caring for older persons, but the evidence suggests that many preventive strategies are effective in this age group. Ironically, the effects of prevention may be greatest in older people because the benefit of preventive activities depends on two basic factors: the prevalence of the problem and the likelihood of an effective intervention. Thus, flu shots may be less likely to work in older people if they are immune compromised, but osteoporosis prevention will be very cost-effective because the baseline levels of the problem, and of falling, are high. Plans for prevention in older people should consider the issues laid out in Table 5–1. Perhaps the most preventable problem connected with caring for older persons is iatrogenic disease.

|

The major thesis here, as with much covered elsewhere in this book, is that age alone should not be a predominant factor in choosing an approach to a patient. A number of preventive strategies deserve serious consideration in light of their immediate and future benefits for many elderly patients.

Preventive activities can be divided into three types. Primary prevention refers to action taken to render the patient more resistant or the environment less harmful. It is basically a reduction in risk. The term secondary prevention is used in two ways. One implies screening or early detection for asymptomatic disease or early disease. The idea here is that finding a problem early allows more effective treatment. The second meaning of secondary prevention involves using the techniques of primary prevention on people who already have the disease in an effort to delay progression; for example, getting people who have had a heart attack to stop smoking. That behavior will not prevent heart disease, but it should reduce the risks of subsequent complications. Tertiary prevention involves efforts to improve care to avoid later complications; proactive chronic disease management is a good example of this approach. As noted in Chapter 4, tertiary prevention is a central part of good geriatric care, which strives to minimize the progression of disease to disability. It requires a comprehensive effort to address both the physiological and environmental factors that can create dependency. All three areas are relevant to geriatric care. Table 5–2 offers examples of activities in each category. Not all the items indicated in this table are supported by clear research findings. Some examples—such as seat belts, exercise, and social support—are based on prudent judgment.

Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

|---|---|---|

Immunization | Papanicolaou (Pap) smear | Proactive primary care |

Influenza | Breast examination | Comprehensive geriatric assessment |

Pneumococcus | Breast self-examination | Foot care |

Tetanus | Mammography | Dental care |

Blood pressure | Fecal blood, colonoscopy | Toileting efforts |

Smoking | Hypothyroidism | |

Exercise | Depression | |

Obesity | Vision | |

Cholesterol | Hearing | |

Sodium restriction | Oral cavity | |

Social support | Tuberculosis | |

Home environmental improvements | PSA | |

Seat belts | ||

Medication review |

The federal government has set health goals for various population groups, including older people. Table 5–3 shows the indicators for older persons identified under the Healthy People program; these measures were selected because they can be derived from available national data sources.

Health status (minimize the following) Physically unhealthy days Frequent mental distress Complete tooth loss Disability (limitation in any way in physical, mental, or emotional problems; need for special equipment) Health behaviors Leisure time physical activity Eating 5+ fruits and vegetables daily Obesity Smoking Preventive care and screening Flu vaccine in past year Pneumonia vaccine ever Mammogram within past 2 years Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy ever Cholesterol checked within past 5 years Injuries Hip fracture hospitalizations |

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is charged with reviewing the evidence on prevention and making recommendations. Tables 5-4 and 5-5 contrast the USPSTF recommendations for topics relevant to older persons with current Medicare policy. It is interesting to note that there are several discrepancies in both directions; some recommended care is not covered, and some care that is not recommended is covered. For example, Medicare will cover prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening, but the USPSTF does not recommend it.

USPSTF recommendation | Medicare coverage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Services | Summary of recommendation | Grade | Coverage frequency |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening | The USPSTF recommends one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) by ultrasonography in men age 65 to 75 who have ever smoked. | B | A one-time screening ultrasound for persons with at least one of the following risk factors:

|

The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against screening for AAA in men age 65 to 75 who have never smoked. | C | ||

The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for AAA in women. | D | ||

Breast cancer screening | The USPSTF recommends biennial screening mammography for women age 50 to 74 years. | B |

|

The decision to start regular, biennial screening mammography before the age of 50 years should be an individual one and take patient context into account, including the patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms. | C | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of screening mammography in women 75 years or older. | I | ||

The USPSTF recommends against teaching breast self-examination (BSE). | D | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of clinical breast examination (CBE) beyond screening mammography in women 40 years or older. | I | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of either digital mammography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) instead of film mammography as screening modalities for breast cancer. | I | ||

Carotid artery stenosis screening | The USPSTF recommends against screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis (CAS) in the general adult population. | D | |

Cervical cancer screening | The USPSTF recommends screening for cervical cancer in women age 21 to 65 years with cytology (Pap smear) every 3 years or, for women age 30 to 65 years who want to lengthen the screening interval, screening with a combination of cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing every 5 years. | A |

|

The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer in women younger than age 21 years. | D | ||

The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer in women older than age 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. | D | ||

The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer in women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and who do not have a history of a high-grade precancerous lesion (ie, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] grade 2 or 3) or cervical cancer. | D | ||

The USPSTF recommends against screening for cervical cancer with HPV testing, alone or in combination with cytology, in women younger than age 30 years. | D | ||

Colorectal cancer screening | The USPSTF recommends screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) using fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy in adults, beginning at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. The risks and benefits of these screening methods vary. | A |

|

The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for colorectal cancer in adults age 76 to 85 years. There may be considerations that support colorectal cancer screening in an individual patient. | C | ||

The USPSTF recommends against screening for colorectal cancer in adults older than age 85 years. | D | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of computed tomographic colonography and fecal DNA testing as screening modalities for colorectal cancer. | I | ||

Coronary heart disease screening | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening with resting electrocardiography (ECG), exercise treadmill test (ETT), or electron-beam computerized tomography (EBCT) scanning for coronary calcium for either the presence of severe coronary artery stenosis (CAS) or the prediction of coronary heart disease (CHD) events in adults at low risk for CHD events. | D | Check cholesterol and other lipid levels every 5 years:

|

The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening with ECG, ETT, or EBCT scanning for coronary calcium for either the presence of severe CAS or the prediction of CHD events in adults at increased risk for CHD events. | I | ||

Dementia screening | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for dementia in older adults. | I | |

Hormone replacement therapy | The USPSTF recommends against the routine use of combined estrogen and progestin for the prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women. | D | |

The USPSTF recommends against the routine use of unopposed estrogen for the prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women who have had a hysterectomy. | D | ||

Osteoporosis screening | The USPSTF recommends screening for osteoporosis in women age 65 years or older and in younger women whose fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors. | B |

|

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis in men. | I | ||

Ovarian cancer screening | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for ovarian cancer. | D | |

Peripheral arterial disease screening | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for peripheral arterial disease (PAD). | D | |

Prostate cancer screening | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening in men younger than age 75 years. | I | |

The USPSTF recommends against screening for prostate cancer in men age 75 years or older. | D | ||

Thyroid disease screening | The USPSTF concludes the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for thyroid disease in adults. | I | |

Vision screening in older adults | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for visual acuity for the improvement of outcomes in older adults. | I | Once every 12 months, which includes:

|

USPSTF recommendation | Medicare coverage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Services | Summary of recommendation | Grade | Coverage frequency |

Alcohol misuse screening and counseling | The USPSTF recommends screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse by adults, including pregnant women, in primary care settings. | B | Medicare covers 1 alcohol misuse screening per year. People who screen positive can get up to 4 brief face-to-face counseling sessions per year. |

Aspirin/NSAIDs for prevention of colorectal cancer | The USPSTF recommends against the routine use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent colorectal cancer in individuals at average risk for colorectal cancer. | D | |

Cardiovascular disease (behavioral therapy) | The USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for men age 45 to 79 years when the potential benefit due to a reduction in myocardial infarctions outweighs the potential harm due to an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. | A | Medicare covers 1 visit per year to help lower risk for cardiovascular disease. During this visit, doctor may discuss aspirin use (if appropriate), check blood pressure, and give tips to make sure people are eating well. |

Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease | The USPSTF recommends the use of aspirin for women age 55 to 79 years when the potential benefit of a reduction in ischemic strokes outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. | A | |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of aspirin for cardiovascular disease prevention in men and women age 80 years or older. | I | ||

The USPSTF recommends against the use of aspirin for stroke prevention in women younger than 55 years and for myocardial infarction prevention in men younger than 45 years. | D | ||

Cholesterol abnormalities in adults (dyslipidemia, lipid disorders) | The USPSTF strongly recommends screening men age 35 and older for lipid disorders. | A | Check cholesterol and other lipid levels every 5 years:

|

The USPSTF strongly recommends screening women age 45 and older for lipid disorders if they are at increased risk for coronary heart disease. | A | ||

The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routine screening for lipid disorders in men age 20 to 35 or in women age 20 and older who are not at increased risk for coronary heart disease. | C | ||

Back pain, low (low back pain) | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the routine use of interventions to prevent low back pain in adults in primary care settings. | I | |

Bacteriuria | The USPSTF recommends against screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in men and nonpregnant women. | D | |

Bladder cancer | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for bladder cancer in asymptomatic adults. | I | |

Blood pressure in adults (hypertension) | The USPSTF recommends screening for high blood pressure in adults age 18 and older. | A | |

Breast cancer, BRCA testing (ovarian cancer) | The USPSTF recommends against routine referral for genetic counseling or routine breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA) testing for women whose family history is not associated with an increased risk for deleterious mutations in breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) or breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2). | D | |

The USPSTF recommends that women whose family history is associated with an increased risk for deleterious mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes be referred for genetic counseling and evaluation for BRCA testing. | B | ||

Breast cancer | The USPSTF recommends against routine use of tamoxifen or raloxifene for the primary prevention of breast cancer in women at low or average risk for breast cancer. | D | |

The USPSTF recommends that clinicians discuss chemoprevention with women at high risk for breast cancer and at low risk for adverse effects of chemoprevention. Clinicians should inform patients of the potential benefits and harms of chemoprevention. | B | ||

Chlamydial infection | The USPSTF recommends screening for chlamydial infection for all sexually active nonpregnant young women age 24 and younger and for older nonpregnant women who are at increased risk. | A | Medicare covers sexually transmitted infection screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and/or hepatitis B for people who meet certain criteria once every 12 months or at certain times during pregnancy. Medicare also covers up to 2 individual behavioral counseling sessions each year for people who meet certain criteria. |

The USPSTF recommends against routinely providing screening for chlamydial infection for women age 25 and older, whether or not they are pregnant, if they are not at increased risk. | C | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for chlamydial infection for men. | I | ||

Lipid disorders | The USPSTF strongly recommends screening women age 45 and older for lipid disorders if they are at increased risk for coronary heart disease. | A | Medicare does not pay for screening per se but will pay if there is a relevant diagnosis. |

The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routine screening for lipid disorders in men age 20 to 35 or in women age 20 and older who are not at increased risk for coronary heart disease. | C | ||

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | The USPSTF recommends against screening adults for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using spirometry. | D | |

Depression in adults | The USPSTF recommends screening adults for depression when staff-assisted depression care supports are in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up. | B | One depression screening per year. The screening must be done in a primary care setting that can provide follow-up treatment and referrals. |

The USPTF recommends against routinely screening adults for depression when staff-assisted depression care supports are not in place. There may be considerations that support screening for depression in an individual patient. | C | ||

Diabetes mellitus | The USPSTF recommends screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with sustained blood pressure (either treated or untreated) greater than 135/80 mm Hg. | B | Medicare covers up to 2 fasting blood glucose tests each year. |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic adults with blood pressure of 135/80 mm Hg or lower. | I | ||

Diet (nutrition) | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet in unselected patients in primary care settings. | I | Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy services prescribed by a doctor for people with diabetes or kidney disease. This benefit includes: an initial assessment of nutrition and lifestyle assessment; nutrition counseling; information regarding managing lifestyle factors that affect diet; and follow-up visits to monitor progress managing diet. Medicare covers 3 hours of one-on-one counseling services the first year, and 2 hours each year after that. |

The USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral dietary counseling for adult patients with hyperlipidemia and other known risk factors for cardiovascular and diet-related chronic disease. Intensive counseling can be delivered by primary care clinicians or by referral to other specialists, such as nutritionists or dietitians. | B | ||

Drug use, illicit | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening adolescents, adults, and pregnant women for illicit drug use. | I | |

Exercise (physical activity) | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against behavioral counseling in primary care settings to promote physical activity. | I | |

Family violence | The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening of parents or guardians for the physical abuse or neglect of children, of women for intimate partner violence, or of older adults or their caregivers for elder abuse. | I | |

Glaucoma | The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening adults for glaucoma. | I | Once every 12 months, which includes:

|

Gonorrhea | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all sexually active women, including those who are pregnant, for gonorrhea infection if they are at increased risk for infection. | B | Medicare covers sexually transmitted infection screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and/or hepatitis B for people who meet certain criteria once every 12 months or at certain times during pregnancy. Medicare also covers up to 2 individual behavioral counseling sessions each year for people who meet certain criteria. |

The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for gonorrhea infection in men at increased risk for infection. | I | ||

The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for gonorrhea infection in men and women who are at low risk for infection. | D | ||

Hearing loss, older adults | NA | NA | |

Hemochromatosis | The USPSTF recommends against routine genetic screening for hereditary hemochromatosis in the asymptomatic general population. | D | |

Hepatitis B virus infection | The USPSTF recommends against routinely screening the general asymptomatic population for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. | D | Medicare covers sexually transmitted infection screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and/or hepatitis B for people who meet certain criteria once every 12 months or at certain times during pregnancy. Medicare also covers up to 2 individual behavioral counseling sessions each year for people who meet certain criteria. |

Hepatitis C virus infection | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in asymptomatic adults who are not at increased risk (general population) for infection. | D | |

The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for HCV infection in adults at high risk for infection. | I | ||

Herpes simplex, genital | The USPSTF recommends against routine serological screening for herpes simplex virus in asymptomatic adolescents and adults. | D | |

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection | The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians screen for HIV in all adolescents and adults at increased risk for HIV infection. | A | Medicare covers HIV screening once every 12 months. |

The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routinely screening for HIV in adolescents and adults who are not at increased risk for HIV infection. | C | ||

Lung cancer | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening asymptomatic persons for lung cancer with either low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), chest x-ray (CXR), sputum cytology, or a combination of these tests. | I | |

Obesity in adults | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen all adult patients for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss for obese adults. | B | Medicare covers intensive counseling to help lose weight. This counseling may be covered if people get it in a primary care setting, where it can be coordinated with the comprehensive prevention plan. |

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of moderate- or low-intensity counseling together with behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss in obese adults. | I | ||

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of counseling of any intensity and behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss in overweight adults. | I | ||

Oral cancer | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routinely screening adults for oral cancer. | I | |

Pancreatic cancer | The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for pancreatic cancer in asymptomatic adults using abdominal palpation, ultrasonography, or serological markers. | D | |

Sexually transmitted infections | The USPSTF recommends high-intensity behavioral counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. | B | Medicare covers STI screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and/or hepatitis B for people who meet certain criteria once every 12 months or at certain times during pregnancy. Medicare also covers up to 2 individual behavioral counseling sessions each year for people who meet certain criteria. |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of behavioral counseling to prevent STIs in non–sexually active adolescents and in adults not at increased risk for STIs. | I | ||

Skin cancer | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of using a whole-body skin examination by a primary care clinician or patient skin self-examination for the early detection of cutaneous melanoma, basal cell cancer, or squamous cell skin cancer in the adult general population. | I | |

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine counseling by primary care clinicians to prevent skin cancer. | I | ||

Smoking (tobacco use) | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians ask all adults about tobacco use and provide tobacco cessation interventions for those who use tobacco products. | A | Medicare will cover up to 8 face-to-face visits during a 12-month period. |

Suicide risk | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening by primary care clinicians to detect suicide risk in the general population. | I | |

Syphilis | The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians screen persons at increased risk for syphilis infection. | A | Medicare covers STI screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and/or hepatitis B for people who meet certain criteria once every 12 months or at certain times during pregnancy. Medicare also covers up to 2 individual behavioral counseling sessions each year for people who meet certain criteria. |

The USPSTF recommends against routine screening of asymptomatic persons who are not at increased risk for syphilis infection. | D | ||

Testicular cancer | The USPSTF recommends against screening for testicular cancer in adolescent or adult males. | D | |

Vitamin D supplementation to prevent cancer and fractures | NA | NA | |

Vitamin supplementation to prevent cancer and coronary heart disease | The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of supplements of vitamins A, C, or E; multivitamins with folic acid; or antioxidant combinations for the prevention of cancer or cardiovascular disease. | I | |

The USPSTF recommends against the use of beta-carotene supplements, either alone or in combination, for the prevention of cancer or cardiovascular disease. | D | ||