ERUS and MRI should be seen more as complementary rather than competitive techniques. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. ERUS is better in showing the tumor extent in small superficial tumors, whereas MRI is superior in imaging the more advanced tumors. The choice of imaging technique depends also on the amount of information that is required for choosing certain treatment strategies, like the distance to the mesorectal fascia for a short course of preoperative radiotherapy. For lymph node imaging, both techniques are at present only moderately accurate, although this could change with advances in new MR techniques.

Surgical treatment of rectal cancer has been plagued by a high local recurrence rate, until in the last decades the role of a good surgical technique and adjuvant (chemo)radiation was fully appreciated. Additionally it was shown that (chemo)radiation was more effective when given before rather than after the resection. Whereas previously most decisions on whether or not to give adjuvant treatment were based on the risk assessment for recurrence through histologic evaluation of the tumor and the lymph nodes, the decisions on neoadjuvant treatment now have to be based mainly on risk assessment through imaging. Although modern CT techniques are improving and are to some extent able to provide information for locoregional staging, endorectal ultrasonography (ERUS) and MRI are considered as the 2 best locoregional staging methods for rectal cancer. When comparing ERUS with MRI, there are several issues that require consideration. In addition to the accuracy in predicting a certain risk factor for local recurrence, there is the treatment strategy that dictates what information will have a clinical consequence, and there are also issues of expertise, availability, and cost. Currently, there is also a trend to study alternative treatment options after a good response to treatment, such as a local excision, or even a nonoperative wait-and-see approach. It is clear that imaging will play an important role in the selection and follow-up of these patients. This new role of imaging to detect small volumes of residual disease in the bowel wall and lymph nodes, sometimes within fibrotic scar tissue, is beyond the scope of this article.

Risk factors for local recurrence

In large databases, the risk factors associated with local recurrence are generally similar to the risk factors for distant recurrence: T stage, N stage, distance to the circumferential resection margin (CRM), perineural invasion, lymph and blood vessel invasion, and histologic grade. Of these risk factors, the T and N stage are commonly used for (neo)adjuvant treatment decisions, and recently the distance to the CRM in clinical settings where a short course of radiotherapy is a treatment option. There is a long history of classifying colorectal cancers using the depth of penetration through the bowel wall and lymph node invasion, a system that has been developed through histologic analysis of the resection specimen. The classification system is highly reproducible through the use of cutoff points that are usually straightforward histologically, such as the distinction between a T2 and T3 tumor depending on ingrowth in the mesorectum or not. This does not always easily transfer to staging through imaging. All imaging methods are good in showing the bulk of the tumor, but will have difficulty in predicting the exact microscopic relation to a histologic interface in a tumor that comes very near to this interface. It is therefore unrealistic to expect 100% accuracy from imaging technology in predicting a histologic classification. Imaging could be helpful in predicting risks for recurrence in its own right with volume and size as prognostic variables. Given the increasing use of preoperative (chemo)radiation in rectal cancer, this should be a topic for further studies. Meanwhile, imaging will continue to try to predict the histologic risk factors.

Tumor Stage

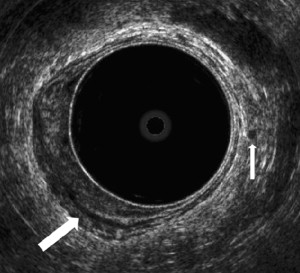

Endorectal ultrasound has been used to assess tumor ingrowth into the bowel wall since the mid 1980s after the description and the results of the technique by Hildebrandt and colleagues and Beynon and colleagues. The different layers of the rectal wall can be seen as 3 hyperechoic and 2 hypoechoic bands, corresponding to the anatomic layers and the interfaces between them. A tumor is shown as a hypoechoic mass. A good overview of staging with ERUS, including the more practical aspects, is provided by Edelman and Weiser. The accuracy of the T-stage assessment in the smaller series is generally about 80% to 90%. Most of the studies are summarized in recent review articles and a meta-analysis comparing ERUS, CT, and MRI. Harewood noted in his review that the larger and more recent studies show lower accuracy rates, and the overall accuracy of 85% in the literature may be an overestimate. Rather than focusing on an overall accuracy estimate, it is more helpful to address specific questions. The overall agreement between uT-stage and pT-stage in the larger studies is 63% to 69%, with 12% to 15% understaging and 18% to 24% overstaging. In these series, there is understaging uT1 in 6% to 24%, and in uT2 stage 16% to 30%. Overstaging in uT3 occurred in 20% to 28%. Some series address the specific question of distinguishing mucosal T0 lesions from T1 tumors, showing a risk of understaging with uT0 of only 5% to 17%. It is generally considered that ERUS is good in imaging the smaller tumors ( Fig. 1 ). For the large lesion, ERUS can identify ingrowth in surrounding structures that are within the field of view such as vagina, prostate, and seminal vesicles. The difficulties arise with tumors located high in the rectum and stenosing tumors, and the overall limited field of view provides insufficient anatomic information in many large T3 to 4 tumors, as described in the section on CRM, later in this article.

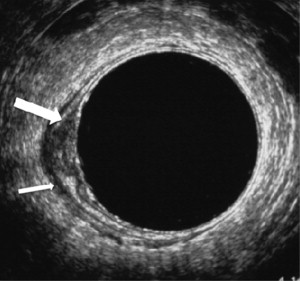

Bipat and colleagues published an extensive meta-analysis in 2004 comparing ERUS, CT, and MRI, including a variety of MR techniques and coils. Overall, the performance of ERUS in T staging was a little better than MRI. In their methodology, the sensitivity and specificity of detecting muscularis propria invasion was 94% and 69% for MRI and 94% and 86% for ERUS. For the detection of perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity and specificity were 82% and 76% for MRI and 90% and 75% for ERUS. In a large recent European study in 11 centers, MR showed an agreement in T-staging of 57% with 19% overstaging and 24% understaging. It also showed to be very accurate in predicting the extramural depth of tumor ingrowth in the mesorectum, a prognostic factor that is not part of the TNM staging system. MRI is good in identifying large T3 and T4 tumors and invasion of the mesorectal fascia, as described later in this article. Because of the accurate depiction of the tumor mass in large tumors, it is often said that with MRI “what you see is what you get” ( Fig. 2 ). Most staging failures with MRI occur in the differentiation between T1 and T2 lesions and between T2 and borderline T3 lesions. A T1 tumor cannot be reliably distinguished from T2 because the submucosal layer is generally not visualized on phased array MRI. Like ERUS, MRI has some difficulty in determining lesions on the border of T2 and T3 with a desmoplastic reaction.

Circumferential Resection Margin

The CRM is the lateral or radial resection margin created by the surgeon. A positive CRM is defined as a closest distance of 1 mm or less between tumor and resection margin, as this represents the optimal prognostic cutoff point. The importance as a prognostic factor and as a parameter of surgical quality has been recognized and confirmed in the past 20 years. The ideal plane of resection in a total mesorectal excision is just outside the mesorectal fascia, and a positive CRM can be the result of inadequate total mesorectal excision (TME) surgery or an advanced tumor that comes close to or invades the mesorectal fascia. The first problem is one of surgical technique, whereas the second is a matter of preoperative identification and adequate neoadjuvant treatment of advanced tumors. For centers that use only a long course of chemoradiation as a neoadjuvant treatment, the distance of the tumor to the mesorectal fascia is usually not very important in the preoperative decision process, as all tumors that extend beyond the muscular wall are considered candidates for a long course of chemoradiation, providing an opportunity for downsizing. For centers that also use a short course of 5 × 5 Gy and immediate surgery, this is different. Although it has been shown that 5 × 5 Gy is a very efficient and cost-effective way to prevent local recurrences in many patients, it is much less effective when the tumor comes close to or invades the mesorectal fascia. These tumors should be identified and treated with a long course of chemoradiation and a long interval to provide downsizing. Regardless of the neoadjuvant treatment strategies, it is important for the surgeon to know the exact anatomic relation of the tumor to the mesorectal fascia and the surrounding structures to obtain a complete resection, and in advanced cases it can be very valuable to have the images available in the operating room.

With ERUS it is very difficult to identify the mesorectal fascia in patients with a “threatened CRM,” except when it shows invasion of vagina, prostate, or seminal vesicles. Many single-center studies have shown that MRI is highly accurate for the prediction of an involved CRM (see Fig. 2 ). The results of a systematic review confirm the high performance of MRI, showing a sensitivity for the prediction of an involved CRM varying between 60% and 88% and specificity between 73% and 100%. The subsequent large European multicenter Mercury study showed an accuracy of 91% with a negative predictive value of 93% for patients who underwent immediate surgery and 77% accuracy and 98% negative predicitve value after a long course of (chemo)radiation. Two European centers that use a short course of radiotherapy as a treatment option report a decrease in the number of positive margins after the incorporation of MRI in the discussion of all patients with rectal cancer in multidisciplinary meetings.

Nodal Stage

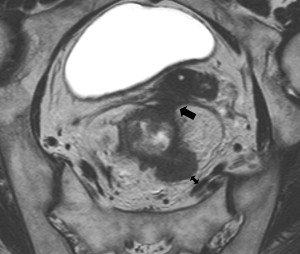

Nodal disease is one of the most important risk factors for both local and distant recurrence, and is generally considered an indication for neoadjuvant therapy. Identifying nodal disease with imaging remains, however, difficult because size criteria used on its own result in only a moderate accuracy. Lymph nodes with a diameter of 10 mm or larger are invariable malignant, but most involved nodes are smaller than 5 mm. In addition to size with 5 mm as a cutoff, ERUS also uses roundness, border irregularity, and hypoechoic nature as criteria for malignancy ( Fig. 3 ). The pooled sensitivity and specificity of ERUS in a recent meta-analysis based on 35 studies was about 75%, and another meta-analysis of CT, ERUS, and MRI showed that the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were only moderate. In the comparative meta-analysis, ERUS performed slightly better than CT or MRI, most likely because of the use of criteria other than size alone. For MRI, the same criteria as on ERUS of roundness and border irregularity, and heterogeneous signal have been found to provide additional accuracy over size alone ( Fig. 4 ). This can be of help in evaluating nodes that are larger than 5 mm, but a reliable characterization in smaller nodes is not possible. The practical difficulties in nodal staging with the standard imaging methods are illustrated by a recent multicenter report in which T3N0 tumors, staged with ERUS or MRI, were found to be node positive at histology in 22%, despite preoperative chemoradiation.