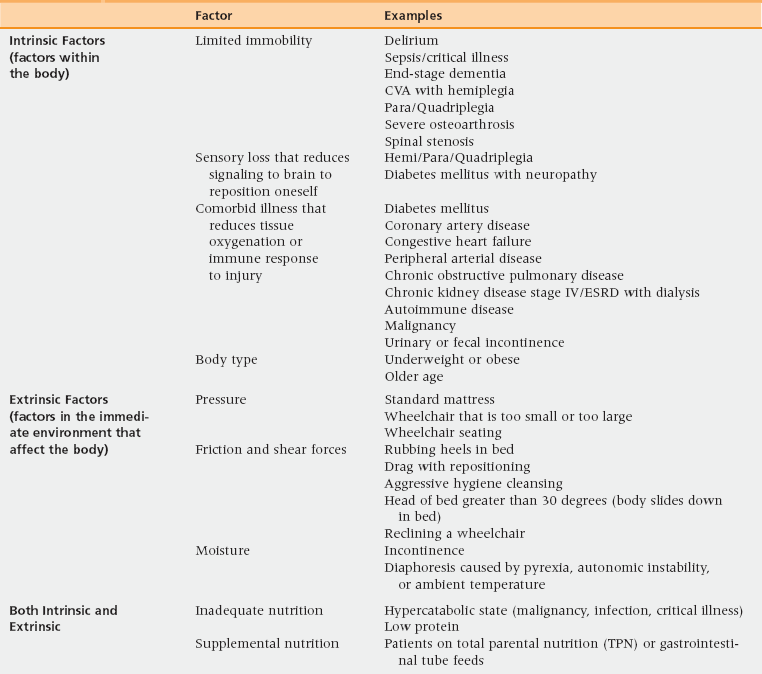

30 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define the stages of pressure ulcers. • Identify the risk factors that place a patient at risk for pressure ulcer development. • Recognize and implement appropriate pressure redistribution strategies for the prevention of pressure ulcers. • Develop and implement a care plan for pressure ulcer management. With an aging population and a trend to provide more health care services in the home, primary care providers find themselves increasingly providing care for patients with pressure ulcers. Incidence rates of pressure ulcers vary widely. In previous studies, pressure ulcers were noted to occur most frequently in acute care settings, with incidence rates as high as 38% in older persons. Efforts have reduced these rates considerably—in the past 10 years hospital incidence rates among older persons have dropped to between 2.8% and 9%. Long-term care and home care settings, in comparison, have incidences that range from 3.6% to 59% and 4.5% to 6.3% respectively.1 The primary care provider, when taking care of a patient with a pressure ulcer, must be mindful of the litigious nature surrounding this geriatric syndrome. Often these ulcers are seen by family and patients as a sign of neglect. Careful assessment, documentation, and multidisciplinary care planning are therefore important both to educate patients and to optimize healing and prevent litigation.2 Pressure ulcers are devastating to the patient and the health care system. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services estimate that the cost per stay for hospitalized beneficiaries with a secondary diagnosis of pressure ulcer is $40,381.3 Annual costs as high as $129,000 have been estimated for the treatment of stage IV pressure ulcers.4 In the Netherlands, where the proportion of elderly persons in the population equals that projected for the United States in 25 to 30 years, one report identified pressure ulcers as that country’s most costly condition, surpassing cancer and cardiovascular disease.5 As of October 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have stopped reimbursing acute care facilities for treatment of pressure ulcers that developed in-house. In 2011 the National Quality Forum considered recommending an expansion of this legislation to include post-acute and long-term care.6 This legislation was based on the belief that pressure ulcers are largely preventable. Although these efforts to improve quality are to be applauded, it continues to be unclear how this decision will impact pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. When an open ulcer is seen on a geriatric patient, pressure ulcer should be at the top of the differential diagnosis. However, there are other causes of skin breakdown, including moisture-associated skin damage, an open abscess, comorbid illness, and malignancy. Table 30-1 reviews the differential diagnoses of ulcerations that are commonly misdiagnosed as pressure ulcers. Of these, several merit note: TABLE 30-1 Differential Diagnosis of Pressure Ulcers • Moisture associated skin damage (MASD) and abrasions are the most common misdiagnosis. Although MASD and friction put the patient at risk of pressure ulcers, a discrete ulceration needs to form to delineate pressure ulcer from these conditions.7 • A diabetic foot or arterial foot ulcer can be difficult to distinguish from a pressure ulcer; however, it is important therapeutically to determine the primary underlying cause. In the case of a diabetic foot ulcer, this would be neuropathy. For an arterial foot ulcer, the cause would be poor arterial flow, with weak or absent pulses a corroborating sign. • Skin changes at life’s end—also known as skin failure—is another increasingly recognized syndrome.8 Thus far it has been challenging to diagnose this condition as distinct from pressure ulcers. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel states that some pressure ulcers are unavoidable. The panel also recognizes pressure ulcers as being separate from skin failure, but that the two diagnoses can coexist. For patients who have an illness that has caused poor tissue perfusion and thus low tissue tolerance to any pressure, the provider should consider documenting the pressure ulcer as “unavoidable” and that skin failure may be occurring.9 Aggressive, 24-hour-a-day prevention efforts in every care setting are critical to limit the development of pressure ulcers. The first step is to be aware of the factors that place patients at high risk. Risk factors are numerous and can be separated between intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors (Table 30-2). TABLE 30-2 Risk Factors for Pressure Ulcers CVA, Cerebrovascular accident; ESRD, end-stage renal disease. • Intrinsic factors are those that alter skin integrity. They include limited mobility; medical comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure or other medical conditions affecting perfusion and oxygenation, malignancy, and renal dysfunction; poor nutrition; and aging skin changes. • Extrinsic factors are those factors that affect tissue tolerance. They include pressure, friction, shear, and moisture. For pressure ulcers, there are two validated and widely used risk assessment tools: the Braden scale and the Norton scale.10 Neither has undergone randomized trials to look at their impact on pressure ulcer incidence.11 Risk assessment should be done on a regular basis and whenever the patient’s condition changes, and the score provided by the tool should be considered supplemental to clinical judgment. The Braden scale has six domains: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear. The first five domains are rated on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being worst and 4 being best; friction/shear is rated from 1 (problematic) to 3 (not a problem). The maximum score is 23. Typically, patients are considered at risk of pressure ulcer development if their Braden score is 18 or lower. Therefore, scores at or below 18 should trigger nursing and other support staff to put in place more aggressive preventive measures, such as frequent turning, a specialized mattress, and perhaps a nutrition consult. The other tool that is often used to assess pressure sore risk is the Norton scale. This uses a 1-to-4 scoring system in rating five domains: physical condition, mental condition, activity, mobility, and incontinence. A score of less than 14 usually indicates a high risk of pressure ulcer development. The Norton scale tends to identify more patients at high risk than the Braden scale.12

Pressure ulcers

Epidemiology and differential diagnosis

Diagnosis

Typical Location

Characteristics

Moisture-associated skin damage (also known as incontinence-associated dermatitis)

Perineum—sacrum, coccyx, gluteal folds, groin folds

Moisture must be present

Indistinct edges

No necrosis

Typically diffuse superficial excoriation, possible fungal appearance

Old pilonidal cyst excision

Gluteal cleft—inferior to coccyx

There is a history of pilonidal cyst excision or a scar is visible

Diabetic foot ulcer

Heel, plantar surface, toes

Neuropathy must be present

Arterial insufficiency–related foot ulcer

Heel, toes

Nonpalpable pulses

Venous insufficiency–related ulcer

On the lower extremity below the knee

Superficial ulcerations with ragged edges

Associated hemosiderin deposition noted on extremity

Edema/blisters

Anywhere on the body

Superficial ulcerations

Tend to be clean

Usually round

Abrasion/friction

Anywhere on body

Skin flap present or abraded/excoriated skin surface

Malignancy

Anywhere on body

Will not heal despite offloading and local wound care

Herpes simplex or zoster

Anywhere on body

Both simplex and zoster have punched out appearance

Tend to start out as blister or painful lesions

Zoster is dermatomal

Abscess

Anywhere on body

Starts as blister or localized swelling that will drain on its own

Risk factors and prevention

Clinical tools to estimate pressure ulcer risk

Pressure ulcers