BACKGROUND

Prepregnancy care for women with diabetes was introduced over 30 years ago and is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes. However, overall pregnancy out-comes remain very poor for women with diabetes with only a third receiving prepregnancy care. Worldwide, Type 2 diabetes is the most common type of diabetes to complicate pregnancy. Women with Type 2 diabetes are more likely to enter pregnancy with obesity and taking potentially teratogenic medications. It is therefore essential that all healthcare professionals delivering diabetes care to reproductive-age women and female adolescents understand the importance of prepregnancy care and are able to provide preconception counseling at routine consultations with women of reproductive age.

HISTORY OF PREPREGNANCY CARE

Molsted-Pedersen first described in 1964 the high incidence of congenital malformations in infants of diabetic women, with 6.4% having a malformation compared to 2.1% of those born to women without diabetes.1 Hyperglycemia was proposed as a possible mechanism with both animal and human studies supporting this hypothesis.2,3 However, the concept of prepregnancy care for women with diabetes to decrease the incidence of fetal malformations was developed after Pedersen observed the relationship between maternal hyperglycemia and the development of fetal anomalies. He noted that, “the occurrence of hypoglycemic reactions and insulin coma during the first trimester was low in mothers with malformed infants indicating a positive relationship between maternal hyperglycemia early in pregnancy and the development of fetal malformations”.4

Judith Steel established a prepregnancy clinic in Edinburgh in 1976.5 The aims of her prepregnancy clinic included:

- Assessment of patients for complications of diabetes

- Explanation of the importance of good glucose control at all stages of pregnancy, and to improve cooperation and motivation

- Optimization of diabetic control at the time of conception

- Encouragement of women to book early for antenatal care.

EFFECTIVENESS OF PREPREGNANCY CARE

Prepregnancy care and congenital malformations

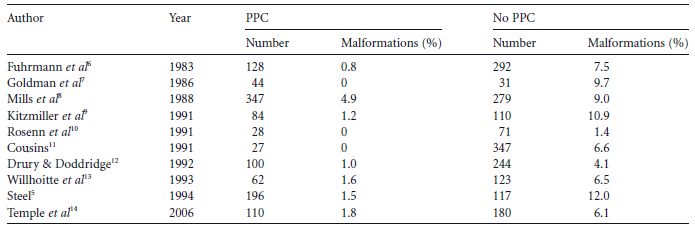

Fuhrmann’s study of 420 women with Type 1 diabetes6 showed that preconception optimization of maternal blood glucose was associated with a significant reduction in congenital malformations. In this study, intensification of glucose control included regular hospital admissions before and during pregnancy, and patients being seen twice weekly. He found a malformation rate of 0.8% in the group that had established preconception glycemic control compared to 7.5% in the control group. Later studies confirmed the effectiveness of prepregnancy care in reducing the risk of malformations (Table 8.1).5,7–14 A meta-analysis of 14 studies of prepregnancy care, which included 1192 offspring of mothers who received prepregnancy care and 1459 offspring of mothers who did not, showed that lack of prepregnancy care was

Table 8.1 Prepregnancy care (PPC) and congenital malformations in Type 1 diabetes. (Data from references 5–14.)

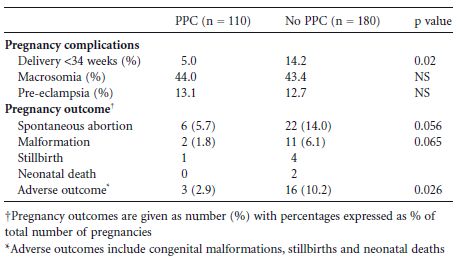

Table 8.2 Prepregnancy care (PPC) and pregnancy outcomes in women with Type 1 diabetes. (Data from Temple et al14.)

Prepregnancy care and spontaneous abortions

Studies have shown that the risk of spontaneous abortion is increased three-to four-fold in women with poor glycemic control in early pregnancy.16,17

One early study showed that prepregnancy care is associated with a reduced risk of spontaneous abortion (8.4% compared to 28%).18 A further study reported that pre-pregnancy care was associated with a strong trend towards a significant reduction in risk of spontaneous abortion (5.7% compared to 14.0%) (Table 8.2).14

Prepregnancy care and perinatal morbidity

There are few data on the effect of prepregnancy care on perinatal morbidity or obstetric complications. A study in Type 1 diabetes showed prepregnancy care was associated with a non-significant reduction in neonatal care admissions (17% vs 34%).19 Further research in 290 women with Type 1 diabetes showed that prepregnancy care was associated with a significant reduction in delivery before 34 weeks of gestation (5.0% vs14.2%).14

Some authors have suggested a link between early glycemic control and risks of macrosomia and preeclampsia.20,21 However, a recent study showed no relationship between prepregnancy care and risk of macrosomia or pre-eclampsia, suggesting that these complications are related to glycemic control in later rather than early pregnancy (Table 8.2).14

Prepregnancy care in Type 2 diabetes

A small number of studies of prepregnancy care and malformation have included women with Type 2 diabetes, but there have been no studies of Type 2 diabetes as a separate group.11,13

One study of 389 women with Type 1 diabetes and 146 women with Type 2 diabetes showed outcomes were significantly poorer in women with Type 2 diabetes, with a four-fold increase in risk of major malformation. The women with Type 2 diabetes, compared to the women with Type 1 diabetes, were less likely to have received any prepregnancy care (28.7 vs 40.5%).22

UK CONFIDENTIAL ENQUIRY INTO MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH

The 2002–2003 UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report has confirmed how poor pregnancy outcomes remain for women with diabetes.23–25 It described 2767 pregnancies in women with Type 1 diabetes and 1041 pregnancies in women with Type 2 diabetes. There was an almost four-fold increase in risk of malformations of the nervous and cardiovascular systems. The study included a confidential enquiry of 222 pregnancies with a poor outcome (death of baby between 20 weeks of gestation and 28 days after delivery or major congenital anomaly), 220 control cases with a good outcome, and also a further 79 cases in women with Type 2 diabetes with a good pregnancy outcome. Its conclusions, in relation to prepregnancy care, are summarized.

WHY DO WOMEN NOT ATTEND FOR PREPREGNANCY CARE?

The CEMACH study showed only a third of women attended for prepregnancy care. In contrast, a nationwide study from the Netherlands showed that 70% women with Type 1 diabetes planned their pregnancies.26

The differences between women who do or do not attend for prepregnancy care have been well-documented (Table 8.3).27,28 In particular, many women with Type 2 diabetes have often received little or no preconception counseling and no prepregnancy care.24

There are no simple solutions to increasing the utilization of prepregnancy care, but the following recommendations may be useful when developing a prepregnancy service.

Table 8.3 Differences between women with diabetes who plan their pregnancy and have prepregnancy care and women who do not.27,28 Factors which may be improved by positive interactions between the provider and his/her patient are shown in bold.

| Pregnancy planned | Pregnancy unplanned |

| Higher socioeconomic status | Lower socioeconomic status |

| Higher level of education | Lower level of education |

| Married or stable | Unmarried or no supportive |

| relationship | partner |

| More likely to have Type 1 | Less likely to have Type 1 |

| diabetes | diabetes |

| Employed | Unemployed |

| Older | Younger |

| European, white | Belonging to ethnic minority |

| group | |

| Non-smoker | Smoker |

| Positive relationship with | Negative relationship with |

| healthcare team | healthcare team |

| Positive preconception advice | Discouraged from pregnancy |

COMPONENTS OF A PREPREGNANCY SERVICE

There are two separate major components to prepregnancy care:

- Preconception counseling, which involves discussion and education

- Prepregnancy care, which involves planning a pregnancy in conjunction with healthcare professionals.

Preconception counseling

Preconception counseling is the education of, and the discussion with, women of reproductive age about pregnancy and contraception. It is an essential component of every consultation in primary and/or specialist care.

- Preconception counseling is complex and not something that can be given in 2 minutes, on just one occasion, at the end of a routine diabetes consultation. It is the responsibility of all healthcare professionals delivering diabetes care to deliver preconception counseling.

- Discussion about future pregnancy plans.

- Education about what prepregnancy care is and how this can improve pregnancy outcomes.

- Education about increased risks of poor pregnancy outcome with poor glycemic control before and during early pregnancy.

- Advice about how to access prepregnancy care, including contact details for self-referral to the prepregnancy care team.

- Education of women with Type 2 diabetes about stopping oral hypoglycemic agents prior to conception and possible need for insulin before and/or during pregnancy.

- Documentation about use of and provision of contraception, and advise about contraception. This may involve a discussion of different types of contraception and how to obtain emergency contraception. It is important to emphasize the importance of continuing reliable contraception until optimization of glucose control has been achieved when planning a pregnancy.

- Education about necessity for commencement of folic acid supplements before pregnancy.

- Education about avoidance of statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) during pregnancy.

- Discussion about how diabetic complications may affect any future pregnancy.

- Information about the importance of urgent referral to a diabetic antenatal clinic should an unplanned pregnancy occur.

- Documentation of any discussion/education. In particular, preconception counseling should be documented at all annual reviews.

Prepregnancy care

Prepregnancy care is the additional care needed to prepare a woman with diabetes for pregnancy, and involves a close partnership between the woman and healthcare professionals. It includes optimization of glucose control, prescribing folic acid supplements, avoidance of potentially teratrogenic medication, and discussion of maternal and fetal risks.

Prepregnancy care should ideally begin 6–12 months before a woman with diabetes embarks on a pregnancy. The time required depends on several factors, including current level of glycemic control and presence of diabetic complications.

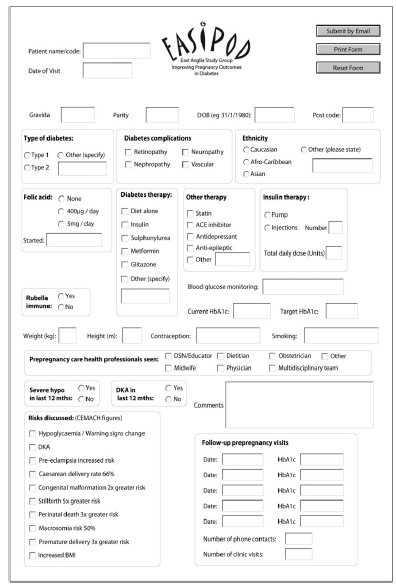

A suggested care pathway is shown detailing the components of prepregnancy care (Table 8.4). It is preferable for prepregnancy care to be delivered by the multidisciplinary team who will care for the woman during her pregnancy, so that relationships between the patient and members of the team can be developed before the pregnancy begins. The use of a prepregnancy proforma may be useful for documentation of all the different aspects of prepregnancy care (Fig. 8.1). The proforma shown has been developed for use in 10 hospitals in one region of the UK, and has been found to be of great use when going through the many different aspects of care needed when delivering prepregnancy care.

When delivering prepregnancy care, it is important to always remember that it is a partnership between the healthcare professionals and the patient, and not a dictatorship.

Glycemic targets

Although glucose targets are suggested in the care pathway, it is important to individualize prepregnancy glycemic targets, aiming for the lowest HbA1c possible while avoiding severe hypoglycemia. Targets should be agreed upon in discussion with the patient and her family. Asking the woman how she perceives her glycemic control may give valuable insight as to how to best advise the patient to optimize her control.

Women with Type 1 diabetes should be encouraged to do up to seven blood glucose tests daily, including some night-time tests, and to record results in a home blood glucose monitoring diary. During the day, tests should be done on waking, before lunch, dinner, and bed, and 1 hour following the three main meals. Downloading glucose meters at clinic visits rather than relying on a patient’s diary of results can be helpful to verify glucose monitoring. A printout of these results at each visit may assist the patient in understanding the rationale(s) for changes in insulin dose, diet distribution, or activity at given times

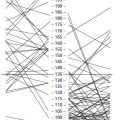

In occasional patients, continuous glucose monitoring systems can be extremely helpful, e.g. to identify erratic blood glucose levels in patients with a suboptimal HbA1c (Fig. 8.2).

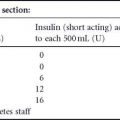

Table 8.4 Prepregnancy care pathway for women with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

| At every visit, ask patient about plans for pregnancy within next 12 months | |

| Keen for pregnancy in next 12 months | No wish for pregnancy in next 12 months |

| Contraception | Contraception |

| Document use of effective contraception | Document use of effective contraception |

| Continue contraception until optimum HbA1c achieved | |

| Optimize glucose control | Document if preconception counseling (see text) |

| Aim for HbA1c as close to normal range as possible without significant hypoglycemia | Continue regular review of glycemic control, screening every 12 months for diabetic complications, education on weight management and smoking cessation |

| Advise HGBM, 4–7 tests daily. | |

| • Fasting glucose <5.6mmol/L (<101 mg/dL) | |

| • Pre-meal glucose <6mmol/L (<108 mg/dL) | |

| • Post-meals <7.8mmol/L (<140 mg/dL) | |

| Intensify insulin regime in T1 DM if needed, e.g. basal-bolus regime or insulin pump | |

| Counsel about lack of data on use of long-acting insulin analogs in pregnancy | |

| If Type 2 diabetes, stop oral agents and initiate insulin if suboptimal glucose control | |

| Hypoglycemia | |

| Educate about increased risk of hypos and loss of hypo awareness during pregnancy | |

| Educate family about use of glucagon | |

| Advise the patient she must test blood glucose before driving and must discontinue driving if she loses hypoglycemic awareness | |

| Diet and exercise | |

| Smoking and alcohol cessation advice | |

| Consider education of carbohydrate counting | |

| Emphasize consistent timing of meals and snacks | |

| Consider recommendation of weight loss (see text) | |

| Encourage regular exercise | |

| Prescribe folic acid supplements | |

| Supplemental dose may be 400 μg to 5 mg daily | |

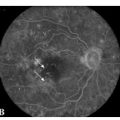

| Screening for diabetic complications | |

| If retinopathy present, refer to ophthalmologist | |

| If proteinuria present or reduced GFR, refer to nephrologist | |

| Assess cardiac status and consider referral to cardiologist | |

| Check thyroid function tests | |

| Review other medication | |

| Stop ACE inhibitors, ARBs, statins, diuretics | |

| Treat hypertension with methyldopa or labetalol | |

| Counsel about risks of diabetes and pregnancy | |

| To fetus: miscarriage, malformation, stillbirth, neonatal death, macrosomia | |

| To pregnancy: eclampsia, premature delivery, cesarean section | |

| To mother: increased risk of severe hypos and DKA. Educate about sick day rules | |

| Risks of retinopathy and nephropathy | |

| Counsel about the risks of development or progression of retinopathy or nephropathy | |

| Consider referral to obstetrician or perinatologist |

HGBM, home glucose blood monitoring; DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis

Fig. 8.1 Prepregnancy proforma dEveloped for use by 10 hospitals within a region of the UK. Educator includes diabetes specialist nurse or certified diabetes educator.