Key Points

- 1.

Lichen sclerosis is associated with vulvar cancer.

- 2.

Treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia III is laser vaporization.

- 3.

Wide local excision is the treatment of choice for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III.

- 4.

Imiquimod treatment is a potentially noninvasive treatment of vulvar dysplasia.

Embryology

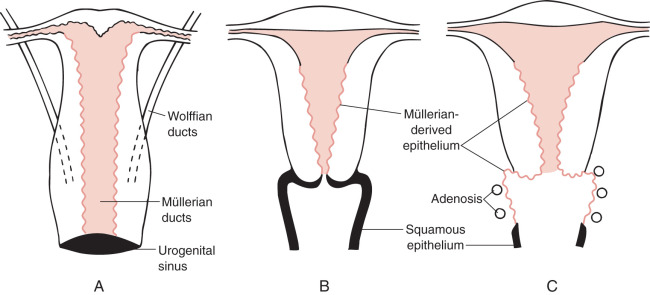

At approximately 12 to 14 weeks of gestation, the simple columnar epithelium that lines the vaginal portion of the uterovaginal canal begins to undergo transformation into stratified Müllerian epithelium. This transformation proceeds cranially until it reaches the columnar epithelium of the future endocervical canal. The vagina, which is lined initially by simple columnar epithelium of Müllerian origin, acquires stratified Müllerian epithelium. The vaginal plate advances in a caudocranial direction, obliterating the existing vaginal lumen. By caudal cavitation of the vaginal plate, a new lumen is formed, and the stratified Müllerian epithelium is replaced by a stratified squamous epithelium, probably from a urogenital sinus origin. Local proliferation of the vaginal plate in the region of the cervicovaginal junction produces the circumferential enlargement of the vagina known as the vaginal fornices, which surround the vaginal part of the cervix.

The administration of diethylstilbestrol (DES) through the 18th week of gestation can apparently result in the disruption of the transformation of columnar epithelium of Müllerian origin to the stratified squamous successor ( Fig. 2.1 ). This retention of Müllerian epithelium gives rise to adenosis. Adenosis may exist in many forms: glandular cells in place of the normal squamous lining of the vagina, glandular cells hidden beneath an intact squamous lining, or mixed squamous metaplasia when new squamous cells attempt to replace glandular cells.

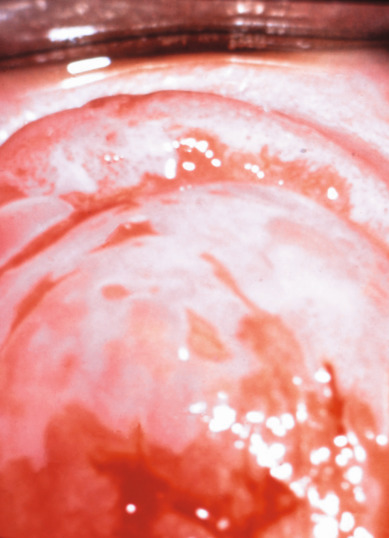

Vaginal adenosis has been observed in patients without a history of DES exposure but rarely to a clinically significant degree. Adenosis is more common in patients whose mothers began DES treatment early in pregnancy and is not observed if DES administration began after 18 weeks of gestation. At least 20% of women exposed to DES show an anatomic deformity of the upper vagina and cervix; transverse vaginal and cervical ridges, cervical collars, vaginal hoods, and cockscomb cervices have all been described. The transverse ridges and anatomic deformities found in one-fifth of women exposed to DES make it difficult to ascertain the boundaries of the vagina and cervix. The cervical eversion causes the cervix grossly to have a red appearance. This coloration is caused by the numerous normal-appearing blood vessels in the submucosa. With a colposcope and application of 3% acetic acid solution, numerous papillae (“grapes”) of columnar epithelium are observed, similar to those seen in the native columnar epithelium of the endocervix. The hood ( Fig. 2.2 ) is a fold of mucous membrane surrounding the portio of the cervix; it often disappears if the portio is pulled down with a tenaculum or is displaced by the speculum. The cockscomb is an atypical peaked appearance of the anterior lip of the cervix, and vaginal ridges are protruding circumferential bands in the upper vagina that may hide the cervix. A pseudopolyp formation (see Fig. 2.2 ) has been described that occurs when the portio of the cervix is small and protrudes through a wide cervical hood.

The occurrence of vaginal adenosis among young women without in utero DES exposure implies that an event in embryonic development is responsible. The development of the Müllerian system depends on and follows formation of the Wolffian, or mesonephric, system. The emergence of the Müllerian system as the dominant structure appears unaffected by intrauterine exposure to DES when studied in animal systems. However, it is apparent that steroidal and nonsteroidal estrogens, when administered during the proper stage of vaginal embryogenesis in mice, can permanently prevent the transformation of Müllerian epithelium into the adult type of vaginal epithelium, thus creating a situation like adenosis. The colposcopic and histologic features of vaginal adenosis strongly support the concept of persistent, untransformed Müllerian columnar epithelia in the vagina as the explanation of adenosis.

Examination and Treatment of Females Exposed to Diethylstilbestrol

Essentially no DES has been prescribed to pregnant women since 1971, when the US Food and Drug Administration issued an alert regarding the risk of vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma for females exposed in utero. The youngest women with in utero exposure were born in 1972, and many previously important clinical topics have become less relevant in everyday practice. The associated congenital anomalies and teenage cancers, for example, are no longer being diagnosed. However, an understanding of the disease process remains essential in order to care for this cohort of women as they age. Additionally, the evolution and understanding of DES is of great historical importance with many implications and lessons for today’s practice.

Approximately 60% of women with in utero DES exposure have vaginal adenosis, cervical-like epithelium in the vagina, which appears red and granular. This is a benign condition that does not require treatment unless symptomatic, and it will generally resolve on its own over time. The premenopausal risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma is approximately 40 times higher among women with in utero DES exposure compared with those without the exposure. In unexposed women, clear cell adenocarcinoma occurs almost exclusively in menopause; in women with in utero exposure, most cases are diagnosed during the late teens and 20s. The oldest reported patient with DES-associated clear cell adenocarcinoma was diagnosed at 51 years. Overall, the incidence of clear cell adenocarcinoma is low in women with in utero exposure (≈1.5 cases/1000 women), but the risk is significantly higher than among unexposed women. The etiology of clear cell adenocarcinoma is unclear, and evolution of adenosis to cancer has never been directly proven, only suspected. Because of an increased risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina and an increased risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), annual examinations with Pap cytology testing are recommended for the entire lifetime of women with in utero DES exposure. No increased association has been observed between DES and squamous cell cervical cancer.

All DES-exposed females should have an annual gynecologic examination with cytology screening ( Table 2.1 ). Cytology should include separate sampling of the cervix and upper vagina. If suspicious lesions are present, colposcopy and directed biopsies should be performed regardless of the cytology results. If delineations of the vagina, cervix, and endocervix are difficult, Lugol’s solution may be helpful in detecting abnormal areas. Colposcopic examination of these patients is hindered by the abnormal patterns seen with squamous metaplasia ( Fig. 2.3 ), which can be confused with neoplastic lesions. Histologic confirmation is essential before any treatment is undertaken. Marked mosaic ( Fig. 2.4 ) and punctation patterns that normally herald intraepithelial neoplasia are commonly seen in the vagina of DES-exposed women as a result of widespread metaplasia. The purpose of regular examination is to permit detection of adenocarcinoma and squamous neoplasia during the earliest stages of development. Although many therapies have been attempted, no recommended treatment plan for vaginal adenosis exists. In most cases, the area of adenosis is physiologically transformed into squamous epithelium during varying periods of observation, and no therapy is necessary.

|

Nonneoplastic Epithelial Disorders of the Vulva

Nonneoplastic epithelial disorders of the vulvar skin and mucosa are frequently seen in clinical practice. Diagnosis is difficult without a biopsy to provide a histologic result, and multiple changes in terminology over the past 25 years add confusion to clinical management. The most recent classification guidelines were published in 2007 by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) ( Table 2.2 ). The lichenoid pattern subset includes two chronic diseases, lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, which are relevant to this review because of the association of those two diseases with vulvar cancer. Lichen simplex chronicus is not included in the lichenoid subset; it is classified in the acanthotic pattern subset. This is appropriate from an oncology viewpoint because lichen simplex chronicus is not associated with invasive cancer. With similar presenting symptoms and a hyperkeratotic appearance, however, lichen simplex chronicus can be difficult to discriminate from lichen sclerosus and lichen planus on examination ( Table 2.3 ).

| Pathologic Subset | Clinical Correlate |

|---|---|

| Spongiotic pattern | Atopic dermatitis |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | |

| Irritant contact dermatitis | |

| Acanthotic pattern | Psoriasis |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | |

| Primary (idiopathic) | |

| Secondary (superimposed on other vulvar disease) | |

| Lichenoid pattern | Lichen sclerosus |

| Lichen planus | |

| Dermal homogenization/sclerosis pattern | Lichen sclerosus |

| Vesiculobullous pattern | Pemphigoid, cicatricial type |

| Linear IgA disease | |

| Acantholytic pattern | Hailey-Hailey disease |

| Darier disease | |

| Papular genitocrural acantholysis | |

| Granulomatous pattern | Crohn’s disease |

| Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome | |

| Vasculopathic pattern | Aphthous ulcers |

| Behçet disease | |

| Plasma cell vulvitis |

| Disorder | Lesion | Genital | Other Locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Erythema with mild scale oval plaques | Mild scaling; also “inverse type” | Central face, neck, scalp, chest, back |

| Psoriasis | Annular scaly plaques that bleed easily | Red plaques with gray-white scale | Scalp, elbows, knees, sacrum |

| Tinea | Annular plaques with central clearing | Common | Skinfolds or single “ringworm” lesion |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Lichenified plaques, some dermatitic | Scrotum or labia majora | Nape of the neck, ankle, forearm, antecubital and popliteal fossae |

| Lichen planus | Flat-topped lilac papules and plaques | White network, erosive vaginitis | Volar wrists, shins, buccal mucosa |

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

Lichen simplex chronicus presents in girls and women of all ages, but it is more common in the reproductive and postmenopausal years. Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic eczematous condition, and most women with this condition also have a history of atopic dermatitis. Pruritus is the most common symptom, and over time, scratching leads to epithelial thickening and hyperkeratosis. The status of the skin usually relates to the amount of scratching. Exacerbating agents may include heat, moisture, sanitary or incontinence pads, and topical agents. Lichen simplex chronicus may be seen in conjunction with other processes such as Candida infections or lichen sclerosus; these primary diseases must be treated in order to treat the pruritus leading to scratching and hyperkeratosis.

The locations most often involved on the vulva include the labia majora, interlabial folds, outer aspects of the labia minor, and clitoris. Changes can also extend to the lateral surfaces of the labia majora or beyond. Areas of lichen simplex chronicus are often localized, elevated, and well-delineated, but they may be extensive and poorly defined. The appearance of lesions may vary greatly even in the same patient. The vulva often appears dusky red when the degree of hyperkeratosis is slight and may appear thickened and leathery when hyperkeratosis persists. At other times, well-defined white patches may be seen, or a combination of red and white areas may be observed in different locations. Thickening, fissures, and excoriations require careful evaluation because carcinoma may be exhibited by these same features. For this reason, biopsy is essential in ascertaining the correct diagnosis.

Biopsy reveals a variable increase in the thickness of the horny layer (hyperkeratosis) and irregular thickening of the malpighian layer (acanthosis). This latter process produces a thickened epithelium and lengthening and distortion of the rete pegs. Parakeratosis may also be present. The granular layer of the epithelium is usually prominent. An inflammatory reaction is often present within the dermis with varying numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Lichen Sclerosus

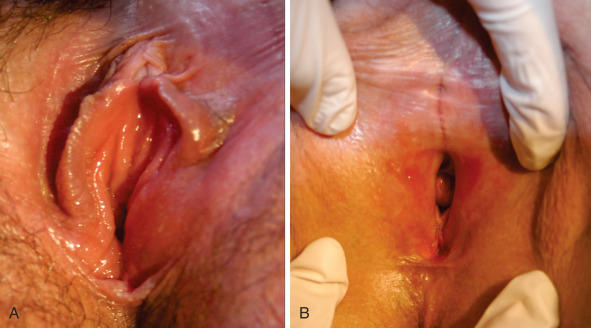

Lichen sclerosus represents a specific disease found in genital and nongenital sites. The vulva is the most common lesion site in women. The age distribution of the disease is bimodal with peaks during the premenarchal and postmenopausal years, but the highest incidence is among postmenopausal women. Although the overall incidence and prevalence are unknown, Leibovitz and colleagues reported the prevalence among elderly women in a nursing home setting as 1 in 30. The mean age in this population was 82 years, 88% were wheelchair users, and 86% were incontinent ( Figs. 2.5 and 2.6 ).

Over time, pruritus occurs with essentially all lesions, leading to scratching, which can develop into ecchymosis and ulceration. Symptoms evolve to include burning, tearing, and dyspareunia. Studies have suggested that the epithelium in lichen sclerosus is metabolically active and nonatrophic. A chronic inflammatory, lymphocyte-mediated dermatosis is present. The etiology of the disease is poorly understood, but autoimmune mechanisms appear to be involved.

The microscopic features of lichen sclerosus include hyperkeratosis, epithelial thickening with flattening of the rete pegs, cytoplasmic vacuolization of the basal layer of cells, and follicular plugging. Beneath the epidermis is a zone of homogenized, pink-staining, collagenous-appearing tissue that is relatively acellular. Edema is occasionally seen in this area. Elastic fibers are absent. Immediately below this zone lies a band of inflammatory cells that is consistent with lymphocytes and some plasma cells. Lichen sclerosus is often associated with foci of both hyperplastic epithelium and thin epithelium. Lichen simplex chronicus has been found in 27% to 35% of women with lichen sclerosus after microscopic study of vulvar specimens, likely secondary to pruritus and scratching.

In a well-developed classic lesion, the skin of the vulva is crinkled (“cigarette paper”) and thinned, or appears parchment-like. The process often extends around the anal region in a figure-of-8 or keyhole configuration, and 30% of women have perianal lesions. At other times, the changes are localized, especially in the periclitoral area or the perineum. Clitoral involvement is usually associated with edema of the foreskin, which may obscure the glans clitoris. Phimosis of the clitoris is often seen late in the course of the disease. As the disease progresses, there is loss of architecture of the normal external genitalia. The labia minora may completely disappear as a result of atrophy. Synechiae often develop between the edges of the skin in these locations, causing pain and limited physical activity. Fissures also develop in the natural folds of the skin and especially in the posterior fourchette. The introitus may become so strictured or stenosed that intercourse is impossible. The vaginal mucosa is generally spared in this disease, which is helpful in discriminating between lichen sclerosus and lichen planus. In a study by Dalziel, 44 women with lichen sclerosus were evaluated for sexual dysfunction. Apareunia was experienced by 19 of the women at some point. Dyspareunia and decreased frequency of intercourse were noted by 80%, and orgasm was altered and relationships were affected in half. Local steroids improved sexual function in two-thirds of these patients.

Lichen sclerosus is a risk factor for invasive vulvar cancer, likely as a result of chronic inflammation and sclerosis. In untreated populations, approximately 5% of patients with lichen sclerosus also have intraepithelial neoplasia. Wallace followed 290 women with lichen sclerosus for an average of 12.5 years and found that 4% ( n = 12) developed vulvar cancer. Carlson et al. reported that 4.5% of patients with lichen sclerosus developed vulvar cancer over a mean of 10 years. In treated populations, however, the risk may be lower. Cooper and associates treated 233 women in a vulvar teaching clinic over a 10-year period; 89% of the cohort received superpotent steroid treatment. Invasive vulvar cancer developed in 3% ( n = 7), and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) developed in 2% ( n = 4). Jones and colleagues reported one case of cancer from a vulvar clinic treating 213 girls and women older than age 8 years. Renaud-Vilmer et al. reported results from an urban dermatology clinic caring for 83 girls and women with no prior treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Invasive cancer was present at the time of presentation in 7% ( n = 6) and developed in 2% ( n = 2); in those who developed cancer, one did not return for follow-up, and one did not use the prescribed treatment. In a cohort followed prospectively with repeat vulvar examinations at the University of Florence by Carli and associates, two cases of invasive cancer and one case of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) developed among 211 women with treated lichen sclerosus. All three cases occurred after more than 3 years of follow-up in the cohort.

The absolute incidence of vulvar cancer is low in women with lichen sclerosus, but 50% to 70% of squamous cell vulvar cancers occur in a background of lichen sclerosus. Currently, there is no diagnostic tool to differentiate between lichen sclerosus that will remain benign versus lichen sclerosus that will evolve into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Two biomarkers, p53 and monoclonal antibody MIB1, have shown promise in retrospective tissues studies, but further testing is necessary. The standard of care for cancer screening in this population remains serial examination with directed biopsies for new, evolving, or suspicious lesions, teaching self-examination with a mirror, and having self-reporting to a physician when lesions change visibly and to palpation.

Lichen Planus

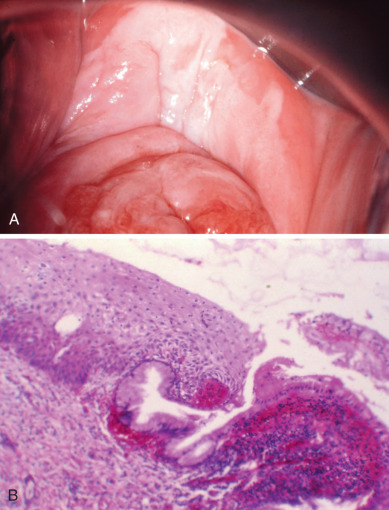

Lichen planus is a distinct dermatologic disease that may affect the oral mucosa, esophageal mucosa, skin, scalp, nails, and eyes in addition to the vulva. Approximately 1% of the population likely develops lichen planus; 25% to 50% of women with lichen planus are believed to have vulvar symptoms. Both vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome and penile-gingival syndrome have been described. The disease appears to be a cell-mediated immune disorder causing chronic inflammation. Similar to lichen sclerosus, symptoms are most common in postmenopausal women in their 50s and 60s; usually include pruritus; and can evolve as the disease progresses to include burning, pain, and dyspareunia. Labial agglutination and loss of architecture of the labia and clitoris may occur. The vaginal mucosa is frequently involved, as opposed to lichen sclerosus, which rarely involves the vagina ( Fig. 2.7 ).

The relationship between lichen planus and vulvar cancer is not as well-established as the association between lichen sclerosus and cancer. Small studies have suggested an increased risk of vulvar cancer, and subjects with oral lichen planus may also have an increased risk of oral cancer. In the early 1990s, case reports by Franck and Young, Lewis and Harrington, and Dwyer and colleagues reported incidences of vulvar SCC in subjects with lichen planus and within erosive lichen planus lesions. In a review of 113 patients with erosive vulvar lichen planus followed by Kennedy and colleagues over an 8-year period, one woman developed vulvar cancer. Of interest, two women in this cohort with oral lichen planus were subsequently diagnosed with oral or esophageal cancer, and two additional women were diagnosed with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ and rectal adenocarcinoma. Similar findings were reported by Cooper and associates. Of 114 women with erosive vulvar lichen planus, seven developed VIN, one developed oral SCC, two developed anogenital SCCs of the labium minora and perianal area.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Biopsies are critical to appropriate management; before any treatment is given on a long-term basis, biopsies should be performed from representative areas to ensure the correct diagnosis. (The exception for biopsy is the pediatric population, which will not be discussed here.) Biopsies should be focused at sites of fissuring, ulceration, induration, and thick plaques. Patient education regarding hygienic measures for keeping the vulva clean and dry is important; any soaps, perfumes, deodorizers, or other contact irritants should be avoided. A thorough history should be taken to evaluate possible causes of vulvar pruritus. After lesions with malignant potential have been ruled out, local measures for control of symptoms, primarily pruritus, can be instituted ( Table 2.4 ). Additionally, infectious vaginitis should be ruled out with a saline wet preparation, potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet preparation, and yeast culture to evaluate for atypical yeast that may be missed on plain microscopy.

| Disorder | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Lichen sclerosus | Topical high-potency steroid ointment |

| Lichen planus | Topical high-potency steroid ointment |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Topical corticosteroid after evaluation and removal of offending environmental agents and treatment of concurrent vaginitis, lichen sclerosus, or lichen planus |

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

Therapy for lichen simplex chronicus is treatment of the underlying cause of irritation and pruritus. All offending environmental agents should be avoided, including wipes, lubricants, sanitary and incontinence pads, detergents, perfumes, and soaps. A thorough history is often necessary to identify possible sources of irritation. Any underlying vaginitis also requires treatment. For isolated lichen simplex chronicus, a topical steroid ointment such as triamcinolone 0.1% or hydrocortisone 2.5% can be applied daily (after bathing to help seal in moisture) until symptoms are improved, generally in 3 to 4 weeks. If symptoms are particularly severe or a course of low-dose steroids is insufficient, a trial of higher dose steroid ointment is acceptable. Pruritus is often most severe at night, and short-term use of a pharmacologic sleep aid may be necessary. Lichen simplex chronicus should resolve with removal of the offending agent and treatment; if symptoms persist or recur, repeat biopsies and the diagnosis should be reconsidered.

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic condition with no curative treatment; the goal is symptom control. The standard treatment for lichen sclerosus is a topical corticosteroid. Typical regimens begin with a superpotent steroid ointment (ie, clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%) used nightly until resolution of symptoms (usually 8–12 weeks). Because of the chronicity of lichen sclerosus, maintenance therapy is necessary after initial treatment; application one to three times per week is usually sufficient. Many women stop treatment when their symptoms improve and then present again months later with recurrent symptoms. Therapy can be reinitiated at treatment levels for 6 to 12 weeks, and emphasis given to maintenance therapy. Theoretically, long-term use of topical steroids may result in striae and thinning of the dermis, but this is infrequently observed in patients with lichen sclerosus. Topical testosterone is no longer the treatment of choice for lichen sclerosus.

A prospective randomized study by Bracco and associates evaluated 79 patients with lichen sclerosus using four different treatment regimens: a 3-month course of testosterone (2%), progesterone (2%), clobetasol propionate (0.05%), and a cream base preparation. Patients experienced greater relief of symptoms with clobetasol (75%) than with testosterone (20%) or other preparations (10%). Clobetasol therapy was the only treatment in which the gross and histologic evaluation of patients improved after treatment. Recurrences after stopping the steroid occurred, but symptoms were relieved when therapy was resumed. Clobetasol was also more effective than testosterone in the randomized trial performed by Bornstein and colleagues, with a significant improvement in long-term relief experience by clobetasol users. Lorenz and colleagues reported 77% had complete remission of symptoms with clobetasol therapy but again noted that maintenance therapy was needed after baseline treatment. In the cohort followed by Cooper and associates discussed previously, 65% were symptom free, 31% had a partial response, and 5% has a poor response after steroid use. Improvement was also seen on physical examination; 23% had total resolution, 69% had partial resolution (improvement in purpura, hyperkeratosis, fissures, and erosions but no change in color and texture), 6% had minor resolution, and 2% had no improvement. Renaud-Vilmer and colleagues noted a different response rate by age group in women treated with 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment. Complete remission, defined as complete resolution of symptoms, normalization of physical examination, and histologic regression of lichen sclerosus, was observed in 72% of women younger than age 50 years, 23% of women between 50 and 70 years, and 0% in women older than 70 years. Relapse was 84% at 4 years but was not associated with subject age.

Occasionally, vulvar pruritus is so persistent that it cannot be relieved by topical measures. Topical treatment may also fail if significant hyperkeratosis is present. In such cases, intradermal and lesional injection of steroids has been reported to be effective. If lesions persist and symptoms do not improve after a course of superpotent topical steroids, biopsies should be repeated to confirm the initial diagnosis. It is again critical to rule out cancer and VIN to ensure appropriate treatment. Other regimens have been reported for lichen sclerosus recalcitrant to corticosteroids. Specifically, tacrolimus and photodynamic therapy may have some efficacy, but further trials are necessary.

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is similarly treated with complete evaluation, patient education, and topical steroids. Additionally, the physical examination should exclude the presence of lichen planus on the skin, scalp, nail beds, and oral mucosa. If systemic disease is present, consultation with a dermatologist is useful. Treatment of vulvar lesions should begin with an ultrapotent steroid ointment (ie, clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%) applied nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. If symptoms improve, the frequency of application can be reduced to two to three times weekly for 4 to 8 additional weeks. Cooper and associates reported that in a cohort of 114 women followed and treated for lichen planus, 71% of those treated with ultrapotent topical corticosteroids experienced relief of symptoms with treatment. On examination, 50% experienced healing of erosions, but no patients had resolution of scarring. When lichen planus symptoms are in a prolonged remission, the lowest effective dose is used for maintenance therapy, which may involve less frequent administration and a lower potency steroid. Similar to lichen sclerosus, symptoms will return if maintenance therapy is not used.

Lichen planus does appear more resistant to therapy than lichen sclerosus. In a small series of women with vulvar lichen planus that was nonresponsive to other treatments, Byrd and colleagues at the Mayo Clinic reported that 15 of 16 subjects experienced symptomatic relief after a course of topical tacrolimus. The mean response time was 4 weeks, and six subjects experienced mild irritation, burning, or tingling that resolved with persistent use. Tacrolimus therapy was less successful in the subjects followed by Cooper and associates, who were nonresponsive to topical steroid treatment. Of seven patients treated, two had complete symptomatic relief, three had some relief, and two had no improvement in symptoms.

Intraepithelial Neoplasia of the Vagina

Clinical Profile

The incidence of VAIN is not well described. The first report was by Graham and Meigs in 1952. They reported three patients with carcinoma of the vagina, two intraepithelial and one invasive, that were discovered 6, 7, and 10 years, respectively, after total hysterectomy for CIS (carcinoma in situ) of the cervix. Carcinoma in situ is a historical diagnosis, equivalent to the modern diagnosis of HSIL or CIN2/3. The most recent analysis of the incidence of VAIN in the United States, published in 1977, reported 0.2 to 0.3 cases per 100,000 women. Data published by Joura and colleagues from a large vaccine trial give a more recent estimate: The incidence of high-grade VAIN in the placebo group—women from 24 countries between 16 and 26 years of age who were followed for a mean of 36 months—was 21 cases in 9087 subjects. There may be multiple reasons for the higher incidence observed in the vaccine trial such as a true rise in incidence since 1977 similar to the increase seen for VIN, a higher rate of diagnosis because the women were being followed with serial examinations, or a different population from a more heterogeneous international setting. VAIN has many of the same risk factors associated with CIN, including smoking, earlier age at first intercourse, increased number of sexual partners, and HPV infection.

CIN of the vagina is much less common than that of the cervix or vulva. For the year 2015, the American Cancer Society estimated that 4080 cases of invasive cancer of the vagina would be diagnosed in the United States. Although the incidence of vaginal cancer has increased over the past several years, it remains rare. Because of the low prevalence of the disease, routine screening for VAIN and vaginal cancer is not recommended. After hysterectomy for benign disease, the incidence of VAIN is extraordinarily low, and guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology (ACOG) and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) do not support Pap testing in this population. These guidelines were written in part based on evidence from Pearce and colleagues, Noller and Stokes-Lampard and colleagues showing that a huge number of women would undergo unnecessary cytology screening and colposcopy in order to diagnose a rare outcome. The exceptions to this guideline include women who have a history of in utero DES exposure, are immunosuppressed, or have a history of cervical or vulvar dysplasia. Many women have accepted historical guidelines recommending annual Pap testing and may require counseling and patient education to accept these new guidelines. Rare, unfortunate cases of VAIN or invasive cancer will occasionally be diagnosed in women who have undergone hysterectomy for benign disease, but these exceptional cases cannot drive screening guidelines. Additionally, because VAIN and vaginal cancer are strongly associated with HPV infection, the HPV vaccination should drive a decrease in the number of these cases in the future.

Patients with VAIN tend to have either an antecedent or coexistent neoplasia in the lower genital tract. This is the usual situation in at least half to two-thirds of all patients with VAIN. In patients who have been treated for disease in the cervix or vulva, VAIN can appear many years later, necessitating long-term follow-up. First van der Linde, then Gusberg and Marshall, and later Parker indicated that 2%, 1.9%, and 0.9% of patients, respectively, had vaginal recurrences after hysterectomy for a similar lesion in the cervix. More recently, Schockaert and associates were able to follow 94 women who had hysterectomies and concurrently carried a diagnosis of CIN II, CIN III, or FIGO stage Ia1 cervical cancer. In a median interval of 35 months, 7.4% ( n = 7) developed VAIN II+ (vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia II or greater), including two vaginal cancers. Ferguson and Maclure reported positive cytologic findings in 151 (20.3%) of 633 previously treated patients. This large group included invasive and in situ cancers of the cervix, which were treated by irradiation or hysterectomy. The long-term recurrence rate for CIS of the vagina is uncertain, but it is sufficient to merit continued careful follow-up.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer are both associated with HPV. HPV positivity rates reported in the literature range from 82% to 94% for VAIN and 60% to 75% for vaginal cancer, and HPV-16 and -18 account for the majority of HPV positivity. In early reports, vaccination appears to be effective at preventing HPV-16– and HPV-18–associated vaginal lesions in women who receive the vaccination before HPV exposure. HPV mapping has shown identical DNA integration loci between primary lesions of cervical dysplasia and later dysplastic lesions of the vagina and vulva, indicating that later disease may result from monoclonal lesions from the primary cervical dysplasia. Vaginal dysplasia appears to mimic cervical dysplasia with a high prevalence of HPV infection, as opposed to vulvar dysplasia, which displays inconsistent associations.

Isolated lesions can usually be recognized colposcopically ( Fig. 2.8 ). The most frequent finding is acetowhite epithelium; mosaicism and punctuation can also be present, and some authors have described a “pink blush” appearance or a slightly granular texture. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy. The extent of the lesion can be evaluated with the colposcope or with Lugol’s solution. Almost all lesions are asymptomatic, although a patient will occasionally have discharge or postcoital staining. An abnormal Pap smear result usually initiates the diagnostic survey. In almost all series, the upper third of the vagina is most frequently involved (as is the case with the invasive variety), and the posterior wall of the vagina appears more susceptible.

Diagnosis

Patients with an abnormal Pap test result who do not have a cervix or patients with an abnormal Pap test result and no cervical abnormality visualized should undergo a careful examination of the vaginal epithelium. Colposcopic examination of the vagina can be difficult to perform. The largest possible speculum should be used and repositioned frequently to allow inspection of all surfaces. Colposcopic findings are similar to those described for the cervix. Each of the four walls should be examined from the apex to the introitus as separate and sequential steps. Small biopsy specimens are taken with a Tischler or Kevorkian–Younge alligator-jaw forceps. Sometimes a sterilized skin-hook for traction at the biopsy site may be helpful. Most patients can tolerate these biopsies without local anesthesia, but the anticipated pain from the biopsies versus pain from a local anesthetic injection should be considered. Lugol’s solution is often helpful in delineating lesions of the vagina. Normal vaginal epithelium is stained brown, but dysplastic lesions with abnormal glycogen levels remain pale. In postmenopausal patients, local use of estrogen creams for several weeks helps to highlight the abnormal areas for identification by colposcopy.

The majority of VAIN is multifocal; even if a lesion is identified, one must search the entire vagina for coexisting, multiple lesions. Lesions are more common in the upper third of the vagina, but disease-free skip areas may be encountered with additional VAIN in the lower vagina. In hard-to-locate lesions, selective cytologic methods, such as obtaining Pap smears from different locations in the vagina, can often pinpoint the area of abnormality so that attention can be paid specifically to the area of highest suspicion.

Management

Local excision of the involved area has been the mainstay of therapy. In many cases, a single isolated lesion can be removed easily in the office with biopsy forceps. If larger areas are involved, an upper colpectomy may be necessary if the lesion is to be removed by surgery. A dilute pitressin solution or lidocaine with epinephrine can be injected submucosally at the beginning of the procedure and will greatly facilitate the vaginectomy.

As in CIN, outpatient modalities of therapy have been investigated for VAIN. Many patients have been treated historically with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), but toxicity generally makes this a less desirable option, particularly in women who are sexually active. However, studies by Petrilli and associates and Caglar and colleagues indicate that this modality can be effective. One of the problems with 5-FU is the selection of the best mode of application, dosage, and length of treatment. Several techniques have been suggested with equivalent results. One-quarter applicator of 5% 5-FU cream is inserted high in the vagina each night after the patient is in bed. The patient can be instructed to coat the vulva and introitus with white petroleum because the cream leaks out during sleep. A small tampon or cotton ball at the introitus is also helpful to prevent leakage. Because of irritation to the vagina and perineum, the cream should be removed by douching with warm water the next morning. This is done every night for 5 to 8 days followed by a 10- to 14-day rest period, and then the application cycle is repeated. This usually allows an adequate treatment time without having the patient experience the tremendous local reaction that can occur with prolonged use. Treatment can be repeated if it is not successful after the first cycle. Weekly insertions of 5-FU cream, approximately 1.5 g (one-third of an applicator), deep into the vagina once per week at bedtime for 10 consecutive weeks has also been shown to be efficacious. Placement of cotton balls at the introitus and application of a petroleum barrier on the perineum and vaginal introitus help prevent 5-FU contamination of the perineum with resultant skin irritation. Douching the next morning, which is advocated by some, is unnecessary with the weekly instillation. Patient compliance is likely higher and toxicity less with the second approach.

Dungar and Wilkinson noted an interesting finding in the vagina after 5-FU therapy, and it has been confirmed by others. After treatment, a red area suggestive of a lack of squamous epithelium may be present. They found that this represented columnar epithelium consistent with a metaplastic process in which squamous epithelium is replaced with columnar epithelium. They called this finding “acquired vaginal adenosis.” These changes are usually found in the upper third of the vagina but may extend into the middle third. The columnar epithelium was of a low cuboidal or mucus-secreting endocervical type. In some cases, squamous epithelium was noted overlying the glandular elements. Marked superficial chronic inflammation was also present. This has also been noted in the vagina after laser therapy.

Cryosurgery has largely fallen out of favor in the treatment of VAIN, and laser therapy is preferred as an ablative technique. To give guidance about the depth of vaginal destruction required by the laser, Benedet and associates evaluated 56 patients who ranged from 22 to 84 years of age. Measurement of the epithelium was performed on involved and uninvolved tissue. The involved epithelium had a mean thickness of 0.46 mm (range, 0.1–1.4 mm). Uninvolved tissue was thinner and had a mean thickness of 0.28 mm. No statistical difference was seen in the thickness of the involved epithelium in the premenopausal and postmenopausal patients; however, the uninvolved epithelium was thinner in the postmenopausal patients compared with the premenopausal patients (0.25 vs. 0.37 mm). Based on this study, the authors believed that destruction of 1 to 1.5 mm would only destroy the epithelium without damaging underlying structures.

Over a 6-year period, Townsend and associates treated 36 patients from two large referral hospitals with a CO 2 laser. In 92% of the patients, the lesions were completely removed by the laser without significant side effects. Almost one-fourth of the patients, however, required more than one treatment session. Krebs treated 22 patients with topical 5-FU and 37 patients with laser therapy. The success rate was similar for the two treatments. Pain and bleeding have been the main complications but appear to be minimal. Healing is excellent, and impaired sexual function has not been a problem. The optimal technique of laser therapy for vaginal lesions has yet to be determined; whereas some investigators suggest removing only the identified lesions, others advocate treating the entire vagina to avoid missing other lesions. A thorough diagnostic investigation of the vagina to rule out invasive cancer can be difficult, but it is obviously mandatory. Evidence from vaginectomy series shows that invasive cancer may be present concurrently with VAIN. In the 105 patients with VAIN II or VAIN III treated with vaginectomy by Indermaur and colleagues, 12% ( n = 13) had invasive cancer on final pathology, and 22% ( n = 23) had negative findings. Multifocal lesions, particularly posthysterectomy, with deep vaginal angles may be difficult to treat with the laser. Small skin hooks and dental mirrors can be used as adjuncts to successful laser therapy.

More recently, experience with 5% imiquimod cream in the management of VAIN has been reported. In a study by Buck and Guth, 56 women with VAIN (mostly low grade) were treated with 0.25 g of the cream placed in the vagina once weekly for 3 weeks. Of 42 women available for follow-up, 36 (86%) were clear of VAIN on colposcopic evaluation 1 week or later after the last treatment. Five patients’ disease required two treatment cycles, and one needed three treatment cycles before clearing of their lesions. Vulvar or vestibular excoriation was reported in only two individuals. No vaginal ulcerations were noted.

Ultrasonic surgical aspiration has been successfully used by Robinson, von Gruenigen and colleagues, and Matsuo and colleagues, but the technique is not widely practiced. Some have advocated surface irradiation using an intravaginal applicator, but adverse effects may be severe and include vaginal stenosis, urinary symptoms, and vaginal ulceration. Additionally, vaginal stenosis can make follow-up extremely difficult. Total vaginectomy, with vaginal reconstruction using a split-thickness skin graft, should be reserved for the patient who has failed more conservative therapy because there appears to be no recurrence benefit from the more invasive procedure.

Treated VAIN often recurs, regardless of the treatment method, and there is no clear standard of treatment. In a retrospective series of 121 women treated for VAIN between 1989 and 2000 by Dodge and colleagues, 33% of subjects experienced recurrence of VAIN, and 2% progressed to invasive cancer; multifocal lesions were more likely to recur. When stratified by treatment type, VAIN recurred in 0% ( n = 0 of 13) of those treated with partial vaginectomy, 38% ( n = 16 of 42) of those treated with laser, and 59% ( n = 13 of 22) of those treated with 5-FU. However, Indermaur and colleagues noted a higher rate of recurrence in their cohort of patients treated with vaginectomy. Of 52 patients available for follow-up who received vaginectomy as treatment for VAIN II or VAIN III, six patients recurred at a mean of 24 months, and one was diagnosed with invasive cancer. Sillman and associates reported on 94 patients with VAIN who were treated by various methods. The remission rate was high, but 5% of the cases progressed to invasive disease despite close follow-up.

Incomplete excision of sufficient vaginal cuff with hysterectomy for CIS of the cervix with involvement of the fornices may explain an early recurrence. The finding of CIS in the vaginal cuff area in less than 1 year after hysterectomy makes this explanation likely. Therefore, it is important to perform a preoperative evaluation of the upper vagina by Schiller tests or colposcopy at the time of hysterectomy for CIS of the cervix. This allows the surgeon to determine accurately how much of the upper vagina has to be removed. It is also apparent that both CIS and dysplasia may develop in the vagina as primary lesions without an association with a similar process on the cervix or vulva. Still other preinvasive lesions of the vagina may appear after irradiation therapy for invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Data from MD Anderson suggest that these postradiation lesions are premalignant and can progress to invasive cancer if they are not treated. Without therapy, approximately 25% of the patients in this series progressed to the invasive state over varying periods of follow-up. Local therapy must be executed with care because of the previous irradiation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree