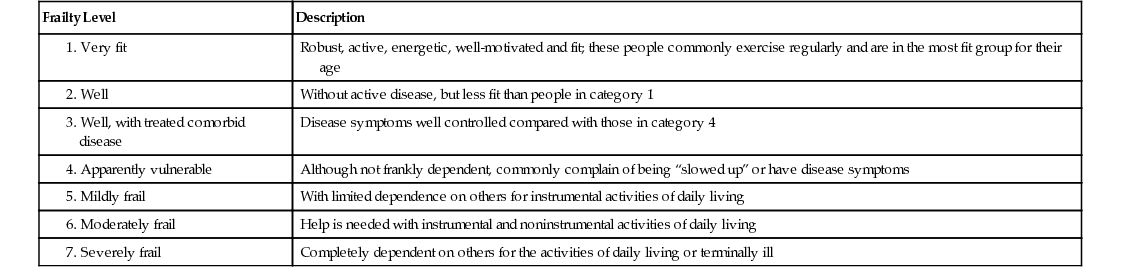

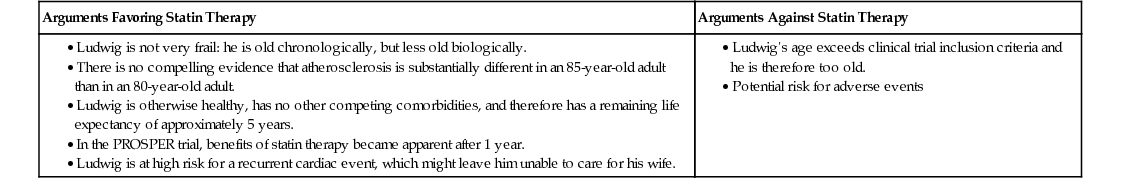

George A. Heckman, Kenneth Rockwood Despite a decline in recent decades in overall cardiovascular mortality in developed countries, the overall burden of cardiovascular disease remains substantial.1 The incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), acquired valvular heart disease (VHD), and heart failure (HF) increases with age, resulting in significant growth in the prevalence of these conditions in the context of population aging.2 The lifetime risk for symptomatic CAD after the age of 40 years is 49% in men and 32% in women, and the average age of patients suffering a first myocardial infarction is 64.9 years in men and 72.3 years in women.2 Of those who die from CAD, over 80% are aged 80 years and older. The prevalence of acquired VHD also rises with age, from less than 2% below the age of 65 years to 13% over the age of 75 years.3 From a population perspective, mitral regurgitation (MR) is the most common form of VHD, followed by aortic stenosis (AS).3 However, among persons referred to hospital with VHD, AS is more common than MR, with a prevalence of 43% and 32%, respectively, in one large European study.3 Finally, the prevalence of HF also rises with age, and octogenarians face a 20% lifetime risk of developing HF.2 Although the burden of heart disease is greatest among older patients, therapeutic recommendations are usually extrapolated from clinical trials conducted on relatively younger, generally healthier, and highly selected patients. Historically, a significant majority of potential candidates for these trials has been excluded because of multiple medical and age-associated comorbidities, a trend that persists today.4,5 Furthermore, clinical trials generally measure “hard outcomes,” such as rates of death or of other cardiovascular events, outcomes that may not be as important to some older patients as quality of life, preserving cognition, or maintaining functional independence in the community. The publication of the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study illustrated some progress made in this regard, as well as the significant gaps that remain.6 In this multicenter randomized controlled trial of 3845 patients aged 80 years and older, treatment of hypertension with indapamide, with or without perindopril for 2 years, was well-tolerated and reduced the risk of stroke, death, and HF; there were no differences in the number of trial participants who experienced cognitive decline.7 In contrast to most prior cardiovascular trials, HYVET specifically targeted older patients, with the average age of participants being almost 84 years, thus filling an important gap in hypertension management literature. However, compared to the general population, HYVET participants had fewer comorbid conditions, were not demented, and outcomes such as functional decline, caregiver burden, or institutionalization have not been reported. Clinicians are thus left with the difficult task of determining how best to apply the results of clinical trials to real-life older patients. The purpose of this chapter is to provide a framework to assist clinicians in the process of determining the most appropriate courses of action for frail older cardiac patients. In patients with cardiovascular disease, older age is often associated with a reduced likelihood of receiving recommended therapies, despite evidence of equivalent, and in some cases, greater benefit than in younger persons with similar conditions.8–12 Underlying these findings appears to be the assumption that aging is a homogenous phenomenon and that all older cardiac patients require the same, often nihilistic, approach. Clearly, people age with variable degrees of success; consider the prominent roles played by Queen Elizabeth and Nelson Mandela well into their 80s. Some octogenarians require caregiver support to remain in their own homes, whereas others require institutional care. When it comes to health, aging is a heterogeneous process, making chronologic age alone an inadequate criterion on which to base treatment decisions. Some of the heterogeneity seen in aging can be accounted for by the development of chronic illnesses. According to the Canadian National Population Health Survey, the proportion of persons with no chronic illness declines with increasing age, from 44% of those aged 40 to 59 years to 12% of those 80 or older.13 In contrast, the proportion of persons with three or more chronic conditions in the same age brackets rises from 12% to 41%, respectively. However, the difference between successful and unsuccessful aging reflects more than just the burden of chronic disease and is a manifestation of underlying frailty (see Chapter 14). Although consensus on an operational definition of frailty has yet to be achieved, frailty can be understood as a state of increased vulnerability to health stressors due to reduced physiologic reserve that is usually, but not exclusively, found in older persons.14 Frailty is not exclusive to chronic disease; whereas some older patients with chronic illness are frail, many are not, and a small minority of frail older persons have no history of chronic disease.15 However, a systematic review has confirmed the strong association between frailty and a wide range of chronic cardiovascular conditions, both clinical and subclinical.16 Furthermore, this association may be, as in the case of HF, bidirectional—frail persons may be more likely to develop HF with time, and patients with HF are more likely to become frail.16 This review also confirms that the presence of frailty in a person with cardiovascular disease is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes, including mortality, morbidity, health service utilization, and impaired quality of life.16 Assessing frailty can be considered akin to estimating a person’s biologic age. A frailty index was developed using data collected from the inception cohort of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA).17 This 20-item index, which considers not only the presence of chronic vascular disease but other symptoms and signs elicited during a structured clinical examination, permits the determination of a person’s biologic age as a reflection of underlying frailty and was shown to be a more important predictor of mortality than chronologic age.17 This approach was recently replicated in a population-based study comparing traditional cardiac risk factors to a frailty index in predicting incident CAD hospitalization and death.18 The frailty index, which consisted of 25 items, including traditional cardiovascular risk factors and conditions usually considered unrelated to CAD, was more predictive of CAD outcomes (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.61; 95% confidence index [CI], 1.40 to 1.85) than traditional risk factors (aHR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.51). These data suggest that chronologic age per se is not an adequate factor on which to base treatment decisions for older persons, but rather that a comprehensive assessment of frailty, reflecting biologic age, provides more useful information on which to base treatment recommendations. Note, also, that patients who have many age-related illnesses also have more deficits. These include subclinical age-related problems, such as motor slowing, abnormal laboratory test results, and less initiative. It is this whole package of health deficits, not just diseases or disabilities, that makes people frail.19,20 This is a triple whammy, in that frail older adults are more likely to become ill and be less likely to respond to and more likely to be harmed by usual care.21 Frailty, as a state of heightened vulnerability, leads to an increased risk of poor outcomes when an affected person is challenged by a health stressor. Conceptually, the degree of risk can be understood as being proportional to the interaction between the degree of frailty and severity of the stressor, which can be expressed mathematically by the following equation: where C is a constant specific to an outcome of interest. Risk, therefore, depends on the particular outcome under consideration, or it can be modified by interventions that focus on frailty itself that mitigate or reduce the impact of a stressor on the individual, or both. This conceptualization of risk has a number of implications: Different outcomes will entail different and potentially competing degrees of risk. Frail individuals may have far more to gain from the success of an intervention than nonfrail individuals; similarly, they may also have far more to lose from adverse events. It is essential to consider patient values and preferences when discussing competing risks. For example, although a patient might benefit from a successful surgical procedure, the risk of an adverse event that could lead to permanent disability—for example, a stroke—might inform their ultimate decision.22 3. Risk can be modified by intervening on the frail state itself, usually through multicomponent procedures such as the comprehensive geriatric assessment (see Chapter 34) or by targeting components of the frail state through focused physical therapy or nutritional interventions.23 Examples of such interventions include senior-friendly hospital strategies (see Chapter 118), modified anesthetic techniques, or minimally invasive surgical techniques.24,25 The case studies discussed in this chapter illustrate how to incorporate these considerations into clinical decision making for older patients with cardiovascular disease. The first is illustrated in Case Study 41-1. Clinical trials have demonstrated that statins reduce the risk of subsequent coronary events and mortality in patients who have suffered a myocardial infarction (MI). However, clinical trials have only included patients up to the age of 82 years.26,27 The family physician must consider whether the results of these trials are applicable to Ludwig, who is 85 years old. Using the CSHA frailty scale (Table 41-1), the family physician determines that Ludwig falls into category 3 (well, with treated comorbid disease), which is associated with a relatively good prognosis and thus corresponds to a biologic age of younger than 85 years.28 In that case, the potential for benefits likely offsets the risk of adverse events.29 The arguments for and against treating Ludwig with a statin are presented in Table 41-2. In this situation, the balance of arguments weighs in favor of offering Ludwig a statin. TABLE 41-1 Canadian Study of Health and Aging Frailty Scale 1. Very fit 2. Well 5. Mildly frail TABLE 41-2 Arguments for and Against Treating Ludwig With a Statin The next study involves Ludwig’s wife, Thelma (Case Study 41-2). Statins are often recommended for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events, although the benefits may be attenuated in older patients with no other concomitant cardiovascular risk factors.30,31 The family physician determines that Thelma falls within category 6 (moderately frail) of the CSHA frailty scale, which is associated with a poor prognosis over the medium term.28 Furthermore, the family physician considers the results of the NHANES I (the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) study, which found that high cholesterol was associated with CAD only in active individuals aged 65 to 74 years.32 Her frailty puts her at increased risk of side effects from the statin, which are not worth the minimal benefits of treatment.29,31 The arguments for and against treating Thelma with a statin are presented in Table 41-3. In this situation, the balance of arguments weighs against offering Thelma a statin. TABLE 41-3 Arguments for and Against Treating Thelma With a Statin In both these cases, considering frailty (biologic age) rather than chronologic age facilitated individualized clinical decision making in the absence of directly applicable evidence from clinical trials. These examples also illustrate the importance of considering patient and caregiver needs and preferences. Case Study 41-3 illustrates the importance of identifying all relevant outcomes and competing risks. In this situation, a successful procedure will allow Ludwig to fulfil his goals; an adverse event might affect his ability to look after his wife, causing her to be institutionalized. However, most clinical trials in cardiology focus on mortality, hospitalization, coronary interventions, and other objective assessments of cardiovascular events. Very few trials have examined outcomes of interest to older adults, such as preventing functional and cognitive decline, caregiver stress, and institutionalization. However, emerging evidence in the treatment of cardiovascular disease has underlined the importance of these domains. Evidence from smaller trials and observational data suggest that the benefits of cardiovascular therapies in older adult patients may include the preservation of function and cognition.33 In a randomized placebo-controlled trial of 60 New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II and III patients with HF from left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction aged 81 ± 6 years, perindopril over 10 weeks was associated with a 37-m increase in 6-minute walking distance compared to baseline versus no significant change in the control group (P < .001).34 A supervised exercise program over 18 weeks in 20 NYHA class III HF patients aged 63 ± 13 years and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less resulted in improvements in psychomotor speed and attention.35 Numerous observational studies have suggested that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors prescribed to older HF patients may result in improved cognition, less depression, slower functional decline, and less institutionalization.33 ACE inhibitors may also preserve cognitive function in hypertensive persons with Alzheimer’s disease, as well as physical function in older persons without HF.36–38 Although these data require confirmation by larger clinical trials, they do support the notion that standard cardiovascular therapies have the potential to address outcomes of importance to frail older adults. Among older adult patients with CAD, increasing numbers of revascularization procedures are being performed. The Trial of Invasive versus Medical therapy in Elderly patients (TIME) trial, one of a few trials to focus exclusively on older adults, randomized 305 patients aged 75 years and older, 78% of whom had chronic Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class III or IV angina despite at least two antianginal drugs, to optimal medical therapy (148 patients) or early invasive therapy (153 patients).39 In the early invasive therapy group, 72% of patients underwent revascularization (28% had coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]), which was associated with an early mortality hazard, but there were no significant mortality differences at 1 and 4 years.40 Early invasive therapy led to greater and more rapid improvements in quality of life and functional capacity than medical therapy, although differences disappeared after 1 year, likely because almost half of the medical therapy patients eventually underwent revascularization. Subsequent health service use was also lower among early intervention patients. The results of this trial suggest that older patients with intolerable angina who proceed with an early invasive approach to treatment face an early mortality hazard that is offset by earlier improvements in quality of life and functional capacity. Patients who tolerate their angina may choose to undergo revascularization at a later date, at the expense of greater health care utilization, but with no overall mortality penalty. The rising number of cardiac surgeries being performed in older adults has been facilitated by improvements in surgical and anesthetic methods over time. As a result, CABG and valve replacement surgeries are being routinely conducted in appropriately selected octogenarians and increasingly among nonagenarians and even centenarians.41–44 Studies of these practices have been primarily observational and have shown significant variability with respect to periprocedural outcomes, with mortality rates in octogenarians ranging from 4% to 14% and rates of stroke ranging from 0.5% to almost 8%.41–44 CABG in older adult patients can lead to significant deconditioning and functional decline, with discharge rates to skilled nursing facilities ranging from 16% to almost 70% and functional recovery taking as long as 2 years.45–53 Postoperative cognitive dysfunction may occur in over 50% of patients following cardiac surgery, and although most recuperate or even improve from baseline, recovery may take up to 1 year.54,55 Clearly, appropriate selection of surgical candidates is often in the eye of the beholder. Although older studies linked adverse outcomes to comorbidities and urgent or repeat revascularization, more recent studies have indicated frailty as an important determinant.56 Combining frailty measures with surgical, physiologic, and functional assessments improves the accuracy of risk stratification in older adults undergoing cardiac surgery.57,58 Following cardiac surgery, frailty has been associated with an increased risk of periprocedural mortality and complications, including delirium, pneumonia, prolonged ventilation, increased length of stay, stroke, renal failure, reoperation, and deep sternal infection.59,60 Frailty is also associated with poor late outcomes. In a cohort of 629 patients age 74.3 ± 6.4 years undergoing percutaneous revascularization, frailty, as measured by the Fried phenotype, was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and death.61 In a retrospective cohort study of 3826 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, frailty, as determined by the presence of functional, cognitive, or gait difficulties, was associated with a greater likelihood of requiring prolonged institutional care after discharge (48.5% vs. 9%; odds ratio, 6.3; 95% CI, 4.2 to 9.4).60 Arguments for and against Ludwig undergoing a coronary intervention are summarized in Table 41-4. Details are described in Case Study 41-4. TABLE 41-4 Arguments for and Against Ludwig Undergoing a Coronary Intervention • He is not frail and therefore is likely to avoid periprocedural and postprocedural complications. • Successful intervention would allow him to continue caring for his wife.

Practical Issues in the Care of Frail Older Cardiac Patients

Introduction

Making Treatment Decisions in Older Adults: Should Age Matter?

Incorporating Frailty Assessment Into Clinical Decision Making

Frailty Level

Description

Robust, active, energetic, well-motivated and fit; these people commonly exercise regularly and are in the most fit group for their age

Without active disease, but less fit than people in category 1

Disease symptoms well controlled compared with those in category 4

Although not frankly dependent, commonly complain of being “slowed up” or have disease symptoms

With limited dependence on others for instrumental activities of daily living

Help is needed with instrumental and noninstrumental activities of daily living

Completely dependent on others for the activities of daily living or terminally ill

Arguments Favoring Statin Therapy

Arguments Against Statin Therapy

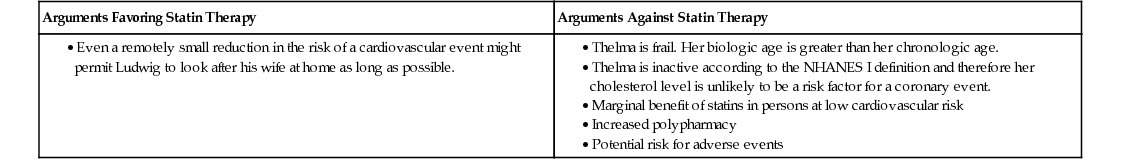

Arguments Favoring Statin Therapy

Arguments Against Statin Therapy

Arguments Favoring Intervention

Arguments Against Intervention

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Practical Issues in the Care of Frail Older Cardiac Patients

41