Elective total hip or knee arthroplasty places patients at risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE). As our understanding of the pathophysiology of VTE after joint arthroplasty has increased, pharmacologic strategies have been developed to target different aspects of the coagulation cascade. Various approaches have been used as risk reduction strategies. In 2011 and 2014 the Food and Drug Administration approved rivaroxaban and apixaban as new oral antithrombotic agents. Although controversies remain with regard to the ideal VTE pharmacoprophylactic agent, this class of novel oral anticoagulants has been demonstrated to be safe and to be more effective than enoxaparin.

Key points

- •

Total hip and total knee arthroplasty put patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism.

- •

Significant research and development has been done in the search for the ideal postoperative thromboprophylactic agent.

- •

Direct factor Xa inhibitors like rivaroxaban and apixaban are novel oral anticoagulants with improved effectiveness and good safety profiles.

- •

Inconsistency across clinical trials with regard to the definition of trial safety endpoints has made it impossible to compare these agents with regard to bleeding.

Introduction

The performance of elective total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) places patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE; Tables 1 and 2 ). These major orthopedic procedures contribute to all 3 components of Virchow’s triad—vascular injury, stasis, and hypercoagulability. This places patients at high risk for the development of thrombosis. The subluxation of the tibia anteriorly during knee replacement surgery or the dislocation of the hip anteriorly or posteriorly in the course of hip replacement surgery imparts traction and torsional forces on blood vessels. This can cause direct vascular endothelial damage that can initiate the process of thrombosis intraoperatively. The period of time spent immobile on the operating room table, exacerbated by use of anesthetic paralytic agents or the use of a tourniquet during knee replacement surgery, further contributes to vascular stasis. As a consequence of the patient’s biologic response to tissue injury, the patient’s circulatory system is showered with tissue thromboplastins, which induces a state of hypercoagulability.

| Type of Surgery | Total DVT (%) | Proximal DVT (%) | Total PE (%) | Fatal PE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip arthroplasty | 42–57 | 18–36 | 0.9–28.0 | 0.1–2.0 |

| Knee arthroplasty | 41–85 | 5–22 | 1.5–10 | 0.1–1.7 |

| Pharmacologic Agent | Relative Risk Reduction (%) Compared with Placebo |

|---|---|

| Total hip arthroplasty | |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 70–71 |

| Aspirin | 0–26 |

| Warfarin | 59–61 |

| Fondaparinux a | 45 |

| Apixaban b | 36 |

| Rivaroxaban c | 48–76 |

| Total knee arthroplasty | |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 51–52 |

| Aspirin | 0–13 |

| Warfarin | 23–27 |

| Fondaparinux a | 63 |

| Apixaban b | 38 |

| Rivaroxaban | 31 |

a Odds reduction for venous thromboembolism for fondaparinux versus enoxaparinparin.

b Cite studies for ADVANCE-1-2-3 (Apixaban Dose Orally vs ANTiCoagulation with Enoxaparin-1-2-3).

c Cite studies for RECORD1-3 (REgulation of Coagulation in ORthopedic surgery to prevent Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism1-3).

As our understanding of the pathophysiology of VTE after joint arthroplasty has increased, various pharmacologic strategies have been developed to directly or indirectly target different aspects of the coagulation cascade. It has been estimated that the postoperative risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) without systemic anticoagulation is as high as 42% to 57% and 85% and the rates of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) was as high as 0.9% to 28% and 1.5% to 10% without thromboprophylaxis after THA and TKA, respectively. It has also been estimated that 45% to 80% of symptomatic VTEs occur after discharge from the hospital. This stimulated significant research and development focusing on the use of in-hospital and extended duration pharmaceutical thromboprophylaxis to reduce the incidence of postoperative DVT and the possible life-threatening sequelae of PE.

According to a 2008 survey among orthopedic surgeons within the United States, there is a consensus that postoperative VTE prophylaxis should be initiated after THA or TKA. However, within the United States, only 47% of THA and 61% of TKA patients are receiving postoperative VTE prophylaxis as recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians. This departure from guidelines is likely multifactorial and may involve issues such as a physician’s poor understanding of the American College of Chest Physicians or American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines as well as orthopedic surgeon concerns regarding safety.

It is acknowledged by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American College of Chest Physicians that the use of routine prophylaxis for the prophylaxis against VTE is indicated in patients undergoing THA and TKA. Dating back to the time of Sir John Charnley, the father of the modern THA, VTE was seen as an important risk to patients after hip replacement surgery. Measures were taken at that time with regard to the use of systemic anticoagulation to decrease this risk. Various approaches such as unfractionated heparin and warfarin were introduced as risk reduction strategies. The use of warfarin has now been established as a standard means to reduce the risk of DVT and PE after joint arthroplasty. Although an effective strategy, the use of an established agent like warfarin has a number of disadvantages. Some patients are seemingly very warfarin sensitive, whereas others are seemingly warfarin resistant. Also, there is no other drug used in arthroplasty surgery with as many food–drug, drug–drug, and disease–drug interactions as warfarin. This can lead to too much or too little anticoagulation of the patient. When using warfarin, taking a careful drug inventory becomes critical to safeguard against the development of potentially serious but largely preventable complications. The requirement to dose adjust warfarin to achieve the desired international normalized ratio target also adds to the complexity of this approach and imposes an additional burden on both the patient and the surgeon. The need for phlebotomy to facilitate blood draws, laboratory analysis to determine the international normalized ratio, and a reporting requirement with associated dose adjustments are just a few of the frustrations commonly associated with warfarin. The use of warfarin after joint replacement surgery continues within the United States, but is used infrequently in other countries.

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) were investigated in the 1980s to address some of the deficiencies and disadvantages associated with the use of warfarin. LMWHs offered more predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. LMWHs of all types (eg, enoxaparin, dalteparen) have been used with great success. They have proven to have good efficacy, a good safety profile, and have eliminated the need for hematologic monitoring. As an alternative to LMWHs, fondaparinux (Arixtra, GlaxoSmithKline) was developed as an indirect inhibitor of factor Xa. This drug represented the pentasaccharide sequence of heparin. It acts on antithrombin, resulting in a conformational change, leading to irreversible binding to factor Xa. With a long half-life of approximately 17 hours in patients with normal renal function, fondaparinux is a true once a day dosing agent. However, concerns regarding its safety in terms of major bleeding in the TKA trials, and the continued need for an injectable route of administration hampered the more widespread use of fondaparinux. The injectable route of administration required for this drug as well as for LMWHs also highlighted the issue of patient noncompliance without appropriate patient instruction. This may be in part owing to this noxious route of administration as compared with an oral route of administration.

Although a number of pharmacologic agents have been found to be effective in decreasing the risk of VTE, each agent has proven to have varying risk/benefit profiles for both the patient and the physician. The ideal thromboprophylactic agent would have the properties of an oral route of administration, a rapid onset of action, a wide therapeutic window, little or no variability in dose response, little or no interactions with food or other drugs, a predictable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics profiles, no routine coagulation monitoring, no required dose adjustments, effective in reducing the risk of thromboembolic events, and a good safety profile in terms of renal, hepatic, cardiac, and hematologic complications such as bleeding.

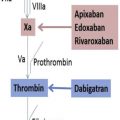

In 2011 and 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Bayer) and apixaban (Eliquis, Bristol-Meyers Squibb), respectively, as new oral antithrombotic agents in the class of drugs known as “direct factor Xa inhibitors,” to reduce the risk of DVT and PE after hip and knee replacement surgery. These agents, also known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), have become increasingly popular owing to their ease of administration, effectiveness in reducing the risk of postoperative DVT and PE, a relatively low incidence of postoperative bleeding and/or wound complications, and the lack of the need for hematologic monitoring to ensure therapeutic dosing. These qualities make rivaroxaban and apixaban ideal choices for decreasing the risk of VTE after hip and knee replacement surgery.

Introduction

The performance of elective total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) places patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE; Tables 1 and 2 ). These major orthopedic procedures contribute to all 3 components of Virchow’s triad—vascular injury, stasis, and hypercoagulability. This places patients at high risk for the development of thrombosis. The subluxation of the tibia anteriorly during knee replacement surgery or the dislocation of the hip anteriorly or posteriorly in the course of hip replacement surgery imparts traction and torsional forces on blood vessels. This can cause direct vascular endothelial damage that can initiate the process of thrombosis intraoperatively. The period of time spent immobile on the operating room table, exacerbated by use of anesthetic paralytic agents or the use of a tourniquet during knee replacement surgery, further contributes to vascular stasis. As a consequence of the patient’s biologic response to tissue injury, the patient’s circulatory system is showered with tissue thromboplastins, which induces a state of hypercoagulability.

| Type of Surgery | Total DVT (%) | Proximal DVT (%) | Total PE (%) | Fatal PE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip arthroplasty | 42–57 | 18–36 | 0.9–28.0 | 0.1–2.0 |

| Knee arthroplasty | 41–85 | 5–22 | 1.5–10 | 0.1–1.7 |

| Pharmacologic Agent | Relative Risk Reduction (%) Compared with Placebo |

|---|---|

| Total hip arthroplasty | |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 70–71 |

| Aspirin | 0–26 |

| Warfarin | 59–61 |

| Fondaparinux a | 45 |

| Apixaban b | 36 |

| Rivaroxaban c | 48–76 |

| Total knee arthroplasty | |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 51–52 |

| Aspirin | 0–13 |

| Warfarin | 23–27 |

| Fondaparinux a | 63 |

| Apixaban b | 38 |

| Rivaroxaban | 31 |

a Odds reduction for venous thromboembolism for fondaparinux versus enoxaparinparin.

b Cite studies for ADVANCE-1-2-3 (Apixaban Dose Orally vs ANTiCoagulation with Enoxaparin-1-2-3).

c Cite studies for RECORD1-3 (REgulation of Coagulation in ORthopedic surgery to prevent Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism1-3).

As our understanding of the pathophysiology of VTE after joint arthroplasty has increased, various pharmacologic strategies have been developed to directly or indirectly target different aspects of the coagulation cascade. It has been estimated that the postoperative risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) without systemic anticoagulation is as high as 42% to 57% and 85% and the rates of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) was as high as 0.9% to 28% and 1.5% to 10% without thromboprophylaxis after THA and TKA, respectively. It has also been estimated that 45% to 80% of symptomatic VTEs occur after discharge from the hospital. This stimulated significant research and development focusing on the use of in-hospital and extended duration pharmaceutical thromboprophylaxis to reduce the incidence of postoperative DVT and the possible life-threatening sequelae of PE.

According to a 2008 survey among orthopedic surgeons within the United States, there is a consensus that postoperative VTE prophylaxis should be initiated after THA or TKA. However, within the United States, only 47% of THA and 61% of TKA patients are receiving postoperative VTE prophylaxis as recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians. This departure from guidelines is likely multifactorial and may involve issues such as a physician’s poor understanding of the American College of Chest Physicians or American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines as well as orthopedic surgeon concerns regarding safety.

It is acknowledged by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American College of Chest Physicians that the use of routine prophylaxis for the prophylaxis against VTE is indicated in patients undergoing THA and TKA. Dating back to the time of Sir John Charnley, the father of the modern THA, VTE was seen as an important risk to patients after hip replacement surgery. Measures were taken at that time with regard to the use of systemic anticoagulation to decrease this risk. Various approaches such as unfractionated heparin and warfarin were introduced as risk reduction strategies. The use of warfarin has now been established as a standard means to reduce the risk of DVT and PE after joint arthroplasty. Although an effective strategy, the use of an established agent like warfarin has a number of disadvantages. Some patients are seemingly very warfarin sensitive, whereas others are seemingly warfarin resistant. Also, there is no other drug used in arthroplasty surgery with as many food–drug, drug–drug, and disease–drug interactions as warfarin. This can lead to too much or too little anticoagulation of the patient. When using warfarin, taking a careful drug inventory becomes critical to safeguard against the development of potentially serious but largely preventable complications. The requirement to dose adjust warfarin to achieve the desired international normalized ratio target also adds to the complexity of this approach and imposes an additional burden on both the patient and the surgeon. The need for phlebotomy to facilitate blood draws, laboratory analysis to determine the international normalized ratio, and a reporting requirement with associated dose adjustments are just a few of the frustrations commonly associated with warfarin. The use of warfarin after joint replacement surgery continues within the United States, but is used infrequently in other countries.

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) were investigated in the 1980s to address some of the deficiencies and disadvantages associated with the use of warfarin. LMWHs offered more predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. LMWHs of all types (eg, enoxaparin, dalteparen) have been used with great success. They have proven to have good efficacy, a good safety profile, and have eliminated the need for hematologic monitoring. As an alternative to LMWHs, fondaparinux (Arixtra, GlaxoSmithKline) was developed as an indirect inhibitor of factor Xa. This drug represented the pentasaccharide sequence of heparin. It acts on antithrombin, resulting in a conformational change, leading to irreversible binding to factor Xa. With a long half-life of approximately 17 hours in patients with normal renal function, fondaparinux is a true once a day dosing agent. However, concerns regarding its safety in terms of major bleeding in the TKA trials, and the continued need for an injectable route of administration hampered the more widespread use of fondaparinux. The injectable route of administration required for this drug as well as for LMWHs also highlighted the issue of patient noncompliance without appropriate patient instruction. This may be in part owing to this noxious route of administration as compared with an oral route of administration.

Although a number of pharmacologic agents have been found to be effective in decreasing the risk of VTE, each agent has proven to have varying risk/benefit profiles for both the patient and the physician. The ideal thromboprophylactic agent would have the properties of an oral route of administration, a rapid onset of action, a wide therapeutic window, little or no variability in dose response, little or no interactions with food or other drugs, a predictable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics profiles, no routine coagulation monitoring, no required dose adjustments, effective in reducing the risk of thromboembolic events, and a good safety profile in terms of renal, hepatic, cardiac, and hematologic complications such as bleeding.

In 2011 and 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Bayer) and apixaban (Eliquis, Bristol-Meyers Squibb), respectively, as new oral antithrombotic agents in the class of drugs known as “direct factor Xa inhibitors,” to reduce the risk of DVT and PE after hip and knee replacement surgery. These agents, also known as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), have become increasingly popular owing to their ease of administration, effectiveness in reducing the risk of postoperative DVT and PE, a relatively low incidence of postoperative bleeding and/or wound complications, and the lack of the need for hematologic monitoring to ensure therapeutic dosing. These qualities make rivaroxaban and apixaban ideal choices for decreasing the risk of VTE after hip and knee replacement surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree