Posterior Flap Hemipelvectomy

Martin M. Malawer

James C. Wittig

BACKGROUND

Despite increasingly effective chemotherapy and advances in limb-sparing surgery around the pelvis and hip, hindquarter amputation (hemipelvectomy) often remains the optimal surgical treatment for primary tumors of the upper thigh, hip, or pelvis.

Hemipelvectomy may also be lifesaving for patients with massive pelvic trauma or uncontrollable sepsis of the lower extremity, and it can provide significant palliation of uncontrollable metastatic lesions of the extremity.9,10,12 An intimate knowledge of the pelvic anatomy (FIG 1A,B) and a systematic approach to the surgical procedure are required to minimize the intraoperative and postoperative morbidity associated with this demanding procedure.

Early descriptions of the surgical technique of hemipelvectomy emphasized the importance of careful selection of patients and immediate replacement of blood loss.2,4,5,7,8,13,14,15,17,18,19,21,22,23,24 Other, later technical descriptions of this procedure have been published.1,3,6,16

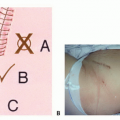

FIG 1 • A. Anatomy of the pelvis. B. Retroperitoneal space and significant anatomic structures. C. Types of hemipelvectomy. (Courtesy of Martin M. Malawer.)

Current terminology for major amputations through the pelvis is overly simplistic and consequently confusing. The terms hindquarter amputation and hemipelvectomy are often used interchangeably to refer to any amputation performed through the pelvis. Older terms used to describe this same procedure include interpelviabdominal17 and interinnominoabdominal22 amputation to describe this same procedure.

The advent of limb-sparing pelvic resections has necessitated a distinction between internal and external hemipelvectomy, depending on whether preservation of the ipsilateral limb is performed. Confusion caused by the term internal hemipelvectomy can be avoided by use of a standardized classification for pelvic resection.

Sugarbaker and Ackerman23 and others have shown the use of a myocutaneous pedicle flap based on the femoral vessels and anterior compartment of the thigh for closure of the wound in patients with tumor involving the posterior buttock structures. This procedure has been termed an anterior flap hemipelvectomy to distinguish it from the more common posterior flap hemipelvectomy. Anterior flap hemipelvectomy is indicated for tumors that involve the buttock and for selected patients who require a well-vascularized flap for coverage.

Other flaps have also been described. The adductor myocutaneous flap is used when anterior or posterior flaps are not possible to obtain.11

There are subtypes of the posterior flap hemipelvectomy.

The term classic hemipelvectomy is used to refer to amputation of the pelvic ring via disarticulation of the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint, division of the common iliac vessels, and closure with a posterior fasciocutaneous flap (FIG 1C). Classic hemipelvectomy is typically necessary for large tumors that arise within the pelvis.

Modified hemipelvectomy refers to a procedure that preserves the hypogastric (internal iliac) vessels and the inferior gluteal vessels supplying the gluteus maximus, permitting creation of a vascularized myocutaneous posterior flap for wound closure. This term also describes variations from the classic operation, including resection through the iliac wing or contralateral pubic rami.

Modified hemipelvectomy is most commonly performed for tumors involving the thigh or hip when a limb-sparing alternative is contraindicated. “Extended hemipelvectomy” refers to a resection of the hemipelvis through the sacral alar and neural foramina, thereby extending the margin for tumors that approach or involve the sacroiliac joint (FIG 2).

Regardless of the type of flap created for closure, the term compound hemipelvectomy is used to describe resection of contiguous visceral structures such as bladder, rectum, prostate, or uterus. (Tumor suspected of extending into viscera or extremely large tumors filling the pelvic fossa can be approached through an intraperitoneal incision.).

ANATOMY

The skeletal anatomy and contents of the pelvis are complex and difficult to visualize without direct experience. Major portions of the gastrointestinal tract, the urinary tract, the reproductive organs, and the neurovascular trunks to the extremities all coexist within the confines of the bony pelvis.

Understanding the three-dimensional anatomy is essential to identifying and protecting these structures during a hemipelvectomy (see FIG 1). The normal anatomy may be distorted by the tumor. Reference to easily palpable and visual landmarks helps identify critical structures.

The surgical approach to a hemipelvectomy is based on sequential exposure and identification of these landmarks and structures.

Bony Anatomy

The basic pelvic bony anatomy is best thought of as a ring running from the posterior sacrum to the anterior pubic symphysis. Major joints include the large, flat sacroiliac joints; the hip joints; and the pubic symphysis. The hip joint is easily located by motion of the extremity; the other joints are easily located and identified by palpation. Other easily palpable bony prominences include the iliac crest, the anterior superior iliac spine, the ischial tuberosity, and the greater trochanter of the femur.

These landmarks are essential in creating rational skin incisions during the procedure. Likewise, identification of internal bony landmarks helps localize adjacent structures.

The lumbosacral plexus is found by palpating the sacroiliac joint, the sciatic nerve and gluteal vessels are found under the sciatic notch, and the urethra is found under the arch of the pubic symphysis.

Vascular Anatomy

Ligation of the correct pelvic vessels is crucial to a successful amputation. The importance of this fact is indicated by the classification scheme, in which the level of ligation determines the type of amputation to be performed. As the abdominal aorta and vena cava descend into the pelvis, they bifurcate, creating the common iliac arteries and veins. This bifurcation typically occurs at L4, with the lower bifurcation occurring at S1. The left-sided aorta and the iliac and external iliac arteries remain anterior to the major veins throughout the pelvis. The internal iliac artery (hypogastric artery) bifurcates from the posterior surface of the common iliac artery as it travels down toward the sciatic notch.

Tumor masses within the pelvis can distort this anatomy, making it mandatory to visualize and isolate each of the vessels before performing a ligation (see FIG 1A).

The internal iliac (hypogastric) vessels supply the pelvic floor, rectum, bladder, and prostate as well as the gluteal muscles. Ligation of this vessel will not jeopardize the internal structures because of contralateral blood flow and rich anastomotic vessels; however, it will significantly devascularize the gluteus maximus muscle. Classic hemipelvectomy, in which these branches are divided, has a substantial rate of wound complications as a direct result.

Pelvic Viscera

In addition to the critical vascular structures, major organs of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts are present and exposed during a hemipelvectomy. These structures should be completely evaluated before surgery.

The bladder and urethra, and the prostate in male patients, are located above and under the pubic symphysis. Placement of a Foley catheter with a large inflated balloon makes these structures easier to palpate during surgery. Care must be taken not to injure the urethra during division of the symphysis. In addition, the venous plexus surrounding the prostate can be a significant source of bleeding that can be difficult to control even with good visualization of the organ. The ureters are at risk of injury as they cross over the iliac vessels from lateral to medial. The peristaltic motion of the ureters helps to identify these structures.

In female patients, the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, and vagina require identification and protection. Care in

taking a complete history of the patient will identify women who have undergone hysterectomies. In female patients who have not undergone such surgery, these organs are found under and adjacent to the bladder. They can be easily and safely retracted out of the operative field.

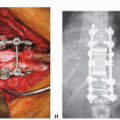

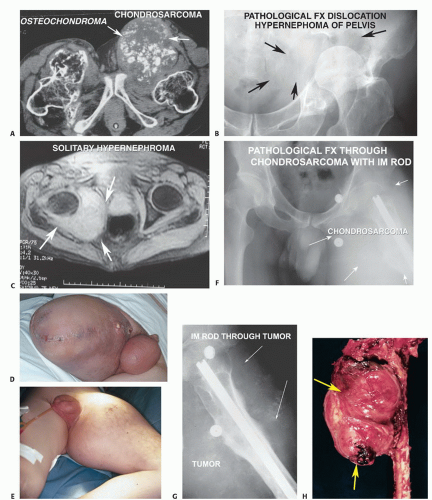

FIG 2 • A. CT scan showing a large chondrosarcoma arising from the left proximal femur. Benign osteochondroma is on the ipsilateral femur. This patient had multiple hereditary osteochondromas. This is one of the more common indications for performing a hemipelvectomy. Chondrosarcoma is the most common malignant tumor of the pelvis. B. Pathologic fracture (distal location) through an extremely large renal cell carcinoma of the left pelvis. There is a large soft tissue component extending almost to the midline. C. Solitary renal cell carcinoma metastasis of the right proximal femur extending into the pelvis. This MRI shows a large extraosseous component with complete destruction of the periacetabular area and with tumor filling the ischiorectal space. Solitary renal cell carcinoma metastasis is considered to be one of the few indications for radical amputation due to metastatic carcinoma. D. Massive sarcoma recurrence of the right thigh following an above-knee amputation. E. Massive swelling of the right thigh following intramedullary rod placement. F. Plain radiograph showing extensive soft tissue swelling from the chondrosarcoma. There is minimal soft tissue calcification. G. Plain radiograph of the proximal femur showing the intramedullary rod extending from the hip distally with contamination of the entire lateral and aspect of the thigh. H. Gross specimen after hemipelvectomy showing an extremely large chondrosarcoma (arrows) arising from the proximal femur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access