Chapter 1 POPULATION HEALTH AND BURDEN OF DISEASE

INTRODUCTION

This chapter introduces the ageing population and its implications for population health and the burden of disease. Special emphasis is given to prevalence data for mental health problems in older people. The chapter also highlights contemporary approaches to epidemiology and health economics as they relate to the mental health of older people. The material presented in this chapter is essential for an understanding of the distribution of mental health problems among older people and is basic knowledge for all mental health workers. More detailed prevalence data are presented in chapters dealing with individual mental health problems.

THE AGEING POPULATION

There is a worldwide trend among developed nations towards population ageing. This trend reflects the combination of steadily rising life expectancy and falling birth rates. Life expectancy is rising due to promotion of healthy lifestyles, prevention of disease and widespread availability of effective medical treatments. Life expectancy in Australia at the age of 65 years is now 82.5 years for males and 86.1 years for females (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007). Falling birth rates are due mainly to improved contraception, later age of marriage, and improved educational and work opportunities for women. The average Australian fertility rate during the period 2000–05 was 1.8 babies per woman. This may be compared with fertility rates for the same period of 2.0 for the United States, 1.3 for Japan and 2.3 for Vietnam (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2007). The replacement fertility rate is the average number of children that each woman needs to have to replace herself and her partner. As the current replacement fertility rate is approximately 2.1, Australia needs an immigration program to maintain or increase its population.

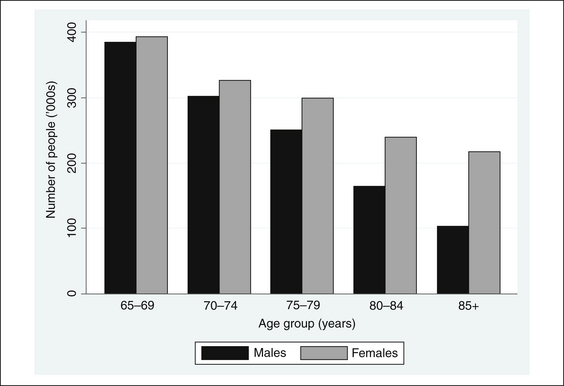

Because women have a longer life expectancy than men, population ageing is associated with population feminisation. Thus, older people are increasingly likely to be women (see Fig 1.1). As a consequence, the prevalence of mental health problems that are more common in women, such as Alzheimer’s disease, will increase beyond that predicted by increasing life expectancy alone. Another consequence of the ageing population is that the ratio between older retired people and younger people of working age is rising. In other words, there are increasing numbers of retired people for every working-age person. This so-called elderly dependency ratio is usually calculated as the ratio between the number of people aged 65 years and over and the number of working-age people. At present, the elderly dependency ratio in Australia is approximately 20%. If retired people are dependent upon working-age people for financial and practical support, then it has been argued that this support will be less available in the future. However, the likely significance of this trend is unclear, as more people will have access to superannuation funds in the future, and medical and technological advances might alter caregiving roles.

Figure 1.1 Older Australians by age and gender

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2007, Table 3.1, p 82).

Australia has one of the highest official marriage rates in the developed world and about 60% of married people can expect to stay married to the same person until one partner dies. However, among people aged 65 years and over, a significant proportion of both men (25.4%) and women (55.6%) no longer have a partner (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2000). As a result, many older people, particularly older women, live alone. Fortunately, 44% of people who live alone own their home without a mortgage (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004).

Homelessness is a highly politicised issue and accurate data are difficult to obtain. However, in the 2001 national census of Australia, an estimate of the extent of homelessness was made (Chamberlain & MacKenzie 2003). There were estimated to be 99,900 homeless people in Australia, of whom 5995 (6%) were aged 65 years and over. There are also a large number of people living in marginal circumstances, such as caravan parks, who are not counted among the primary homeless in the census. This is an important issue for community mental health services as a high proportion of homeless people have a mental health problem. However, older people are underrepresented among the homeless and are not targeted specifically by programs for the homeless. As an illustration of this, in 2007–08, Australian Supported Accommodation Assistance Program (SAAP) services were accessed by 159 of every 10,000 people aged 15–19 years, but by only 8 of every 10,000 people aged 65 years and over (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009b).

Most of the people seen by older persons’ mental health services (OPMHS) are retired from the paid workforce. In Australia in 2007, 84.4% of women and 67.7% of men aged 65–69 years reported that they were retired. In comparison, 97.1% of women and 90.8% of men aged 70 years and over were retired (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009). Although only 16% of retired people reported that superannuation was their main source of retirement income, this proportion is expected to rise as greater numbers of older people have access to compulsory superannuation funds. About 40% of working-age Australians over the age of 45 plan to cut down their working hours before retiring (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2009).

HOSPITAL CARE

People aged 65 years and over are more likely to be admitted to hospital than younger people and have a higher average length of stay than any other age group, apart from children aged less than one. The term ‘hospital separation’ refers to the number of people leaving hospital through discharge or death. Hospital separation statistics are complex, but it is instructive to look briefly at how separations for depressive episodes in women vary by age. In 2007–08, 5121 women aged 25–34 years, 7424 women aged 35–44 years, 6472 women aged 45–54 years, 4984 women aged 55–64 years, 2936 women aged 65–74 years, 2611 women aged 75–84 years and 860 women aged 85+ years left hospital after a depressive episode (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009a). Among people aged 65 years and over, Indigenous Australians accounted for 11.5% of hospital separations, whereas non-Indigenous Australians accounted for 37.4% of separations. However, people living in very remote areas have a separation rate 50% higher than the rest of the population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009a).

RESIDENTIAL AGED CARE

OPMHS deal commonly with people living in residential aged care environments or receiving care at home. In 2008, there were 175,472 Commonwealth-supported residential aged care places in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009c). In addition, there were 40,280 Community Aged Care Packages (CACP), 4244 Extended Age Care at Home (EACH) packages and 1996 EACH Dementia packages (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009). Current planning targets call for 113 places and packages per 1000 people aged 70 years and over. These targets include 44 high-care places, 44 low-care places, and 25 community-care packages, of which four are for high care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009). There has been a steady increase in the proportion of residential aged care facility (RACF) residents who require high care. This currently stands at approximately 70% of all residents. On 30 June 2008, there were 157,087 permanent residents and 3163 respite residents in aged care facilities in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009c).