Tumor

Clinical manifestations

Laboratory evaluation

Preferred treatment modalities in children

Prolactinoma

Pubertal arrest, galactorrhea, menstrual abnormalities, pituitary deficiencies, visual symptoms, and headache

Elevated serum PRL+/− elevated serum GH

1. Dopamine antagonists such as bromocriptine, pergolide, and cabergoline

2. Transsphenoidal surgery

Corticotropinoma

Weight gain, growth arrest, hypertension and striae, premature adrenarche/hirsutism, menstrual irregularities, insulin resistance

Tests for Cushing Syndrome: 24 h UFC, low dose dexamethasone suppression test, BIPSS

Transsphenoidal surgery

Somatotropinoma

Gigantism before epiphyseal closure, acromegaly, glucose intolerance/diabetes, visual symptoms, headache, hyperprolactinemia symptoms

Random GH, IGF-1, oral glucose tolerated test, TRH test

Somatostatin analogs: octreotide long-acting agents (dopamine agonists)

Nonsecreting adenoma

Growth or pubertal failure, visual symptoms, headache, pituitary deficiencies

Transsphenoidal surgery

21.2.6 Treatment

In pediatric patients, the primary management of pituitary adenomas is medical or surgical, depending on the type of adenoma, and is shown in Table 21.1. The preferred surgical technique is transsphenoidal resection (TPR). TPR can be undertaken with very low rates of morbidity and mortality rate of approximately 0.5%. This is particularly true at large volume surgical centers with experienced surgeons. The most common complications of TPR include diabetes insipidus and fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. More serious complications like meningitis, vision loss, stroke, and cerebrospinal fluid leak occur in 1.5% of cases (Barker et al. 2003). In a series limited to pediatric patients, surgeons using microscopic endonasal TPR were able to achieve gross total resections (GTR) in 24 of 29 patients with tumors not involving the cavernous sinus, but only 2 of 7 patients with tumors involving the cavernous sinus. Normal pituitary function was restored in 19 patients without adjuvant treatment, the average hospital stay was 1.6 days, and serious surgical complications were limited to one case of sinusitis (Tarapore et al. 2011).

There is concern for the late effects and risks of radiation therapy. Therefore radiation therapy is reserved for cases of uncontrolled functioning tumors or patients with unresectable residual disease.

21.2.7 Radiation Therapy Techniques

When radiation is employed to treat pediatric patients with pituitary adenomas techniques are similar to those used in adults. For patients with tumors that are at least 3 mm from the optic chiasm and/or optic nerves, stereotactic radiosurgery is usually an option. For other tumors, conventionally fractionated radiation therapy is employed.

21.2.7.1 Conventionally Fractionated Radiation Therapy

When treating with conventionally fractionated radiation, the gross tumor volume (GTV) is defined by the MRI imaging and planning CT. Fine cut imaging, preferably less than 2 mm slices, is preferred for optimal tumor delineation. A clinical target volume (CTV) expansion may not be necessary for a tumor that is not infiltrative. A CTV expansion of 5 mm may be employed in areas where tumors are seen to be invasive, along the skull base, or in the cavernous sinus. Planning target volume (PTV) expansions of as small as 3 mm can be employed with daily image guidance, depending on the treating institution. Often the entire sella turcica is encompassed in the PTV. In addition to the target volumes, normal structures contoured should include the optic apparatuses (eyes, lacrimal glands, optic nerves, and optic chiasm), lens, hippocampus, and temporal lobes. The prescribed radiation dose is dependent on whether the tumor is a functioning or nonfunctioning PA. Nonfunctioning adenomas can be treated with 45–50.4 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions. Functioning PAs should be treated with 50.4–54 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions. In addition to photon radiation, conventionally fractionated proton radiation has been described (Wattson et al. 2014).

21.2.7.2 Stereotactic Radiosurgery

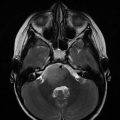

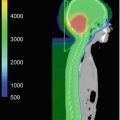

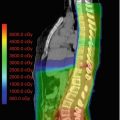

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) provides the most conformal external beam radiation with the logistical advantage of a single fraction of radiation. This intervention can be delivered with either Gamma Knife (Elekta Instrument, Stockholm, Sweden) or linear accelerators. The GTV is pituitary adenoma and the prescribed dose is typically 15 Gy (12–20 Gy) to the tumor surface (50% isodose line with Gamma Knife) for nonfunctioning adenomas and 25 Gy (15–30 Gy) in functioning pituitary adenomas. The optic chiasm dose should be restricted to ≤9 Gy. An example is shown in Fig. 21.1.

Fig. 21.1

Gamma knife planning for pituitary adenoma involving the left cavernous sinus. Axial, coronal, and sagittal views on T1-weighted MR scans. The 50% isodose line covers the lesion completely

21.2.8 Outcomes

Most reports are from series that are composed mostly or completely of adult patients. Outcomes are measured in terms of tumor volume, biochemical control, and sequelae of treatment. Tumor control greater than 85% is anticipated whether patients are treated with fractionated radiation therapy or fractionated SRS. In most series of patients treated with SRS, the tumor was controlled in greater than 90% of cases. Biochemical or hormonal control is not as excellent as tumor control.

Corticotropinoma. In a review of 5 series involving 241 patients (including treated with SRS, conventionally fractionated photon radiation, and proton radiation) published between 2013 and 2014, the tumor control rates ranged from 83 to 100% and the biochemical remission rates were 22–76% (Tritos and Biller 2015). In a somewhat older review from 2002, 10 studies in which 255 patients were treated with fractionated radiation therapy had remission of Cushing’s disease occurred in 55–100% of patients but at the expense of pituitary function in 14–56% of patients. The time to remission ranged from 4 to 26 months. Among 185 patients treated with SRS on 8 studies, the biochemical complete response rate was 63–100%, but occurred earlier than with conventionally fractionated radiation (Mahmoud-Ahmed and Suh 2002).

Somatotropinomas. In a review of 9 series of patients treated with conventionally fractionated radiation therapy, between 5 and 70% achieved remission, with the largest series (884 patients) achieving a 60% remission rate. Growth hormone reduction lagged tumor size regression, the former taking place over years. With stereotactic radiosurgery, biochemical remission rates range between 23 and 50% with side effect of hypopituitarism developing in up to 20% of patients (Castinetti et al. 2009).

Prolactinomas. Compared to other functioning PAs, prolactinomas are associated with the poorest metabolic control rates. In a recent review of SRS series published since 2000, the average endocrine remission rate was 34.7% using a median marginal dose of 24 Gy. The mean post-radiosurgery hypopituitarism rate was 14.8% (Ding et al. 2014).

Nonfunctioning PAs. In a review of 9 studies that included 1261 patients treated with conventional fractionation, the 10-year control rate was 74–97%. In 21 studies that included 648 patients, the local control with stereotactic radiosurgery was 88–100%. Up to a quarter of patients in these series developed pituitary dysfunction following radiation (Kanner et al. 2009).

21.3 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Involving the Pituitary Gland

21.3.1 Epidemiology and Predisposing Factors

LCH is caused by infiltrating CD1a+/CD207+ pathologic dendritic cells forming inflammatory lesions. It is typically characterized by skin and bone lesions, although other organ systems can be involved including the liver, spleen, bone marrow, lung, bone marrow, and central nervous system—including the pituitary gland. The incidence of LCH is between 2 and 10 children per million (Guyott-Goubin 2008). The median age at presentation is 1.8 years and the frequencies of presentations with single organ involvement and multi-organ involvement are approximately equal (Bhatia et al. 1997). LCH can infiltrate the hypothalamus and/or posterior pituitary gland and cause diabetes insipidus (DI). It is estimated that 5–50% of patients with LCH have DI and it is often associated with skull lesions that may precede the DI (Grois et al. 1995; Dunger et al. 1989). DI can present before or after the presentation of other LCH lesions (Prosch et al. 2004; Donadieu et al. 2004). There is conflicting data regarding whether systemic treatment of LCH presents subsequent development of DI (Donadieu et al. 2004; Grois et al. 2006; Chellapandian et al. 2015). Recurrent BRAF mutations have been found in 57% of LCH lesions (Badalian-Very et al. 2010). Patients are risk-stratified by organ system involvement; pituitary gland involvement without involvement of the liver, spleen, or bone marrow is considered low-risk.

21.3.2 Radiographic Findings and Workup

Patients often present with an erythematous, papular rash resembling a diaper rash. They may also have a focal painful bone lesion that appears as a well-circumscribed lytic lesion on plain films. Such patients should undergo a bone survey to look for additional lesions. The diagnosis is confirmed with positive immunohistochemical staining of S100 and CD1a and the presence of Birbeck granules on electron microscopy as seen in Fig. 21.2 (Badalian-Very et al. 2013). Patients with DI by history and laboratory evaluation, or patients with LCH lesions of the facial bones or anterior or middle cranial fossa, should also undergo an MRI of the brain with particular attention to the T1 sequences of the pituitary gland pre- and post-gadolinium. It is common to find absence of the bright spot or infundibular thickening on T1-weighted sequences, the latter demonstrated in Fig. 21.3.