Perspectives in Cancer of the Head and Neck

Eugene N. Myers

PERSPECTIVES IN HEAD AND NECK CANCER

In the years which have passed since the 4th Edition of Cancer of the Head and Neck, many changes have taken place in the management of benign and malignant tumors of the head and neck. When my career as a head and neck surgeon began 46 years ago, most cancers of the head and neck were treated surgically using an external approach. Halsted’s concept of en bloc resection to be certain that the cancer was adequately removed often left the patient with cancer of the head and neck a functional cripple and a dreadful sight to behold. The only flaps available were delayed from a distant site such as the abdomen or the back. This form of reconstruction took many months, and by the time the patient’s reconstruction had been completed, often the cancer had recurred. The patient who underwent a total laryngectomy had little chance of ever speaking again and became a social outcast.

Radiation therapy was used with curative intent to treat early cancers of the tonsil and larynx or those deemed unresectable. Salvage surgery for those who failed radiation was fraught with danger due to the high doses used and because little attention was given to the fact that these patients were nutritionally depleted. This set of circumstances led to poor wound healing, necrosis of skin flaps, carotid artery blowout, and death. Even those who survived had great difficulties swallowing and often spent their remaining time on earth being nourished through a gastrostomy tube.

Chemotherapy was in the early developmental phase and used exclusively in the setting of massive local regional recurrence or distant metastasis. Thus, each of the major modalities used to treat head and neck cancer today was quite primitive in comparison to today’s state-of-the-art treatments.

A major advance in head and neck surgery occurred in 1965, when Dr. Bakamjian1 introduced the deltopectoral flap. I performed many of these flaps during my fellowship with Dr. John Conley in 1967. This was a game changer since it was the first regional flap that could be used nondelayed in the reconstruction of the head and neck. The fact that even the largest wound could be reliably reconstructed immediately pushed the envelope so the surgeons could take on more advanced cancers and create more radical operations. This flap was largely replaced when the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap was introduced by Dr. Steven Ariyan in 1979.2 This flap could also be used without delay, and creative surgeons have found many uses for this flap, which is widely used even today.

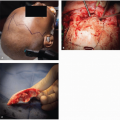

Cranial facial surgery for skull base tumors was first described by Dr. Alfred Ketcham3 at the NIH in 1963, and this technique still plays an important role in the management of these tumors despite the introduction of endonasal endoscopic skull base surgery.

During my career, I have witnessed the introduction of many new techniques including transoral CO2 laser microsurgery for vocal cord cancers by Strong and Jako4 and the use of this technology by Steiner5 in the excision of cancers of the supraglottis and hypopharynx. Weinstein et al.6 later adapted the surgical robot (da Vinci) to successfully remove cancers of the oropharynx. The use of these techniques has preserved the historic role of the surgeon as a key individual in the management of cancer of the head and neck.

For those unfortunate patients who require total laryngectomy, the introduction of microvascular free tissue transfer has played a major role in reconstruction of these wounds particularly in the setting of postradiation salvage surgery. Singer and Blom7 made a huge contribution to the quality of life of these patients when they introduced the valve that uses pulmonary-driven air to allow the patient to speak by occluding the stoma—a powerful contribution, beautiful in its simplicity.

The importance of the surgical robot was grasped by many head and neck surgeons who recognized the versatility and precision built into this machine. O’Malley and Weinstein8 developed the transoral robotic surgery (TORS) technique, which has provided a corridor to resect cancers of the base of the tongue thereby eliminating the need for the classic external approaches such as the transhyoid or transmandibular approach of yesteryear. With the current epidemic of HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma in a younger, healthier, nonsmoking population, the TORS approach fills the need for complete cancer resection with clear margins with preservation of swallowing function. The swallowing function was often compromised after larger external techniques were used as well as with patients who in recent years had been treated with nonsurgical means by chemoradiation. When it was recognized that these cancers were more curable in this subset of patients, Genden et al.9 recognized the advantage of “dose de-escalation,” which included primary TORS surgery and when necessary postoperative radiation therapy in lower doses that preserved swallowing function eliminating the patient’s long-term dependence on PEG tubes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree