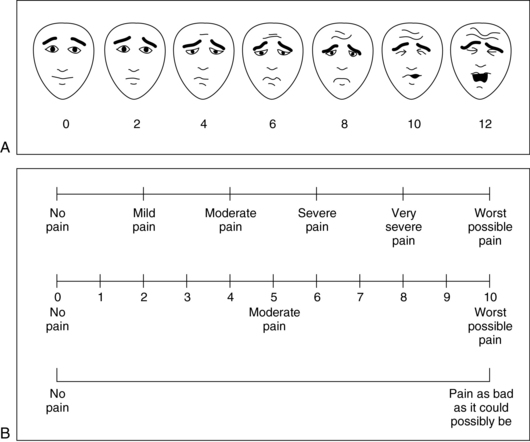

27 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define persistent pain and discuss its impact on older adults. • Discuss the pathophysiology of persistent pain. • Describe age-related changes that influence the presentation and treatment of persistent pain. • Take an accurate pain history and use assessment tools to quantitate and monitor pain syndromes. • Choose appropriate pharmacologic treatments to manage persistent pain. • Apply nonpharmacologic approaches to the treatment of pain. However, especially among the elderly, pain is often ongoing without a single incident that causes the pain. Previously this was referred to as chronic pain. However, because the term chronic is frequently associated with a negative connotation the preferred term to describe such pain is persistent pain. Contrary to common misconceptions, persistent pain has a distinct pathologic basis, causing changes in the nervous system that often worsen over time.1 Persistent pain is commonly encountered in a geriatric practice. It is estimated that 25% to 50% of the elderly may have persistent pain.2 Sixty-five percent of nursing home residents report having inadequately treated pain.1 However, a recent study3 looked at the long-term persistence of musculoskeletal pain in community-dwelling older adults. Over a 6-year period, approximately 20% of the study participants had no musculoskeletal pain, one third had persistent pain, one third had intermittent pain, and one sixth had pain in each of the 6 years. However, half of those with pain during one of the years had no pain during any of the other 5 years. This could imply that pain, while common, may be a more dynamic symptom than previously thought. Persistent pain has a significant negative impact on patients’ lives (Box 27-1). Sleep disturbances, feelings of loneliness, depression, and social isolation are all more common in those with persistent pain. Patients with persistent pain have a reduced ability to carry out their social roles in their family or place of work. In addition, persistent pain often results in limited physical activity in patients, thereby worsening their physical conditioning. It is estimated that the total cost of pain in the United States is between $560 and $635 billion in 2010 dollars. The cost to Medicare is believed to be approximately $65.3 billion, which is 14% of the Medicare budget. These figures do not include lost productivity or lost tax revenue. Disability from all causes costs the United States $300 billion annually, with the persistent pain–related causes of arthritis and back/spine pain being the top two causes of disability.4 It is sometimes helpful from a clinical standpoint to classify persistent pain in pathophysiologic terms.2 Nociceptive pain comes about from stimulation of peripheral pain receptors and may be from tissue or joint inflammation or degeneration, continuing injury, or skin or internal organ noxious stimulation. Inflammatory or degenerative arthritis, myofascial pain syndromes, or ischemia are examples of such pain. Pain with this etiology responds to usual analgesic medications and nonpharmacologic strategies. Neuropathic pain results from abnormal nerve stimulation that involves peripheral or cranial nerves. Examples include diabetic or idiopathic peripheral neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, or phantom pain. Pain of this etiology is often more difficult to treat and may not respond completely to any treatment. Medications used include certain antidepressants or anticonvulsants. Another category is pain of mixed or uncertain etiology. Examples include recurrent headaches, vasculitis, somatization, or conversion reactions. Treatment of this category is difficult and should be individualized for each patient. There is a difference in pain perception and tolerance when comparing the elderly with younger people. Myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers are decreased in density in the elderly with prolonged latencies noted in peripheral sensory nerves. This slows transduction and transmission of the pain signals.5 There is a lower density of descending pain inhibiting nerve fibers in the elderly. In addition there is a slower recovery from hyperalgesic states6; once pain is established these changes may make it more likely that persistent pain develops after a noxious insult. Most studies indicate that there is an increase in pain threshold with aging.2 There is also an age-related decrease in the willingness to endure strong pain. From a clinical standpoint, such changes may be evident in the different pain presentations that the elderly have with either an acute myocardial infarction or a ruptured appendix. There are many tools to assess pain in the elderly, both the cognitively intact and the cognitively impaired.7 The most reliable way to evaluate the severity of pain of a cognitively intact patient is simply to ask the patient his or her estimate of the pain.2 For those with mild to moderate dementia, reliable pain scales are available for use (Figure 27-1). Patients with advanced dementia are more difficult to evaluate, but clues from the patient’s behavior or actions may be helpful.8,9 Grimacing, grunting, or constant movement may be clues to uncontrolled pain. The mental status of the patient often deteriorates with persistent pain. Figure 27-1 Pain intensity scales used in older patients. A, Faces scale. Ask the patient to “put an X by the face that best matches the severity of your pain right now.” B, Visual analog scales. Ask the patient to “circle the number that best represents the intensity or severity of your pain right now.” (A from the Pediatric Pain Sourcebook [copyright 2001], the International Association for the Study of Pain. B redrawn from Carr DB, et al. Acute pain management: Operative or medical procedures and trauma. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1992 [AHCPR 92-0032], and Jacox A, et al. Management of cancer pain. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994 [AHCPR 94-0592].)

Persistent pain

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology

Pain quantitation

Persistent pain