41 Peripheral Nerve Tumors and Tumor-Like Conditions

Peripheral nerve tumors and tumor-like conditions are being increasingly well characterized and understood. There has been a particular increase in experience and expertise with imaging of peripheral nerve lesions. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound facilitate identifying tumors of peripheral nerves and often distinguish between benign and malignant disease. They also help distinguish many tumors from other tumor-like lesions that may not require biopsy for diagnosis. They can localize the safest site for biopsy with the highest yield. Clinical patterns can be correlated with radiological findings to help establish the correct diagnosis or generate a differential diagnosis, but misdiagnosis is common and leads to suboptimal treatment. Ultimately, familiarity with these clinical and radiological patterns can improve patient outcomes. This chapter discusses the role that pattern recognition plays in determining the effective treatment for these peripheral nerve lesions.

General Principles

General Principles

Clinical Evaluation

Patterns are established with a good history and clinical examination supplemented by tests and imaging. Evaluation of the tests and imaging may be done in conjunction with a neurologist, geneticist, oncologist, or oncologic surgeon. The imaging studies and the planning and interpretation of new studies should be reviewed with a radiologist. Similar discussions should be held with a neuropathologist.

Pearl

• Clinical patterns can be correlated with radiological findings that can often help establish the correct diagnosis or generate a differential diagnosis. Familiarity with these patterns can improve patient outcomes.

Radiological Evaluation

Magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound,18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET), and computed tomography (CT) are useful modalities in the evaluation of peripheral nerve tumors. The development and availability of 3-tesla (T) MRI has led to a significant growth in peripheral nerve imaging, and MRI is the best single imaging tool available for evaluating peripheral nerve tumors and tumor-like conditions.1,2 High-resolution MRI requires not only an MRI with increased field strength, but also knowledge of proper radiofrequency coil use and sequence selection to produce optimum images. The evaluation of peripheral nerve tumors is best performed with the use of intravenous gadolinium. Postgadolinium enhancement characteristics are a critical component in the evaluation of peripheral nerve tumors and tumor-like conditions and gadolinium should be included in the MR evaluation unless contraindicated. In the future, MRI techniques such as three-dimensional (3D) isotropic and diffusion tensor imaging may prove to be valuable sequences in the evaluation of the peripheral nerves.

Pearl

• High-resolution MRI with standard imaging sequences and the clinician’s knowledge of patterns of peripheral nerve tumors and tumor-like conditions are the most valuable tools in peripheral nerve imaging.

The lumbosacral plexus and brachial plexus can be imaged with standardized MRI protocols. The basic components should include the key sequences of high-resolution T1-weighted, fluid sensitive, and postgadolinium fat-saturated sequences. The fluid-sensitive sequences vary depending on preference and include different methods of fat saturation, such as inversion recovery, chemical saturation, and Dixon separation techniques. Imaging planes for the brachial and lumbosacral plexus should be altered from standard anatomic planes to better visualize the oblique course of these structures. The evaluation of peripheral nerves outside of the plexus can be successfully performed with the proper knowledge, but often requires a tailored protocol for each study. Excellent multi-planar MRI studies can be performed easily in localized lesions of the extremities, but become challenging in lesions that are poorly localized clinically, and multiple coil types and patient positions may be required to evaluate a region suspected of having a nerve lesion.

Intraneural location, solitary versus fascicular, internal signal characteristics, and degree and pattern of enhancement are important features for developing a differential diagnosis. MRI can localize mass lesions as intraneural or extraneural. Once a lesion has been identified as intraneural, high-resolution imaging can differentiate a solitary intraneural mass from a plexiform process. Solitary intraneural masses can be evaluated for location within the nerve, that is, central versus eccentric, which may aid in planning for surgical resection. The internal signal characteristics are evaluated using muscle as an internal control for T1- and T2-weighted signal characteristics. Homogeneity, heterogeneity, and patterns of postgadolinium enhancement are used to determine the composition of tumors and in the identification of tumor-like conditions. This combination of imaging characteristics can often lead to a confident diagnosis without the need for biopsy.

• Magnetic resonance imaging studies of lesions in the extremities that have not been well localized clinically may require multiple coil types and several patient positions.

Treatment

Performing preoperative biopsy of mass lesions remains controversial. At some institutions, image-guided biopsy of nerve tumors is routinely performed when they are not characteristic on imaging or they have features that provoke concerns about malignancy. Having a diagnosis in these cases facilitates treatment planning, as neoadjuvant therapy is indicated for some malignant tumors. Potential problems that have been described with biopsy include new neurologic deficit or pain, inadequate or faulty biopsy, and tumor seeding, but these are rare. The advantages of biopsy outweigh the potential disadvantages. The open surgical technique of targeted fascicular biopsy (Fig. 41.1) can be used to evaluate lesions in patients with otherwise indeterminate neuropathies who have MRI abnormalities without an overt mass-like lesion.3 These patients often have had extensive evaluations, in many instances having had unrevealing distal cutaneous nerve biopsies or unsuccessful empiric treatment.

Symptomatic lesions should be resected whenever possible. The goal should be maintaining neurologic function. When this is not possible or not obtained, consideration should be given to reconstruction if feasible, either in the early or later stage depending on circumstances. Different options might be available ranging from nerve surgery (nerve grafting or nerve transfers) to secondary reconstruction (such as tendon transfer, free muscle transfer, or other soft tissue or bony procedures). For malignancies, chemotherapy or radiation might well be indicated. Patients should be reevaluated in the immediate postoperative period. A baseline imaging study is often helpful to gauge complete resection. In many instances, long-term clinical and imaging follow-up is recommended.

Controversy

• There is no consensus of the role of preoperative biopsy for mass lesions of the peripheral nerves.

Fig. 41.1 Targeted fascicular biopsy. This drawing shows schematically how an MRI abnormality is utilized along with clinical and operative data to select the region of a nerve for open biopsy (Used with permission of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2013. All rights reserved.)

Benign Nerve Sheath Tumors

Benign Nerve Sheath Tumors

Pattern

Schwannomas (neurilemommas) and neurofibromas are the most common benign nerve sheath tumors. Sporadic cases are more frequently schwannomas. Syndromic cases are often neurofibromas with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and schwannomas with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), or schwannomatosis. Hybrid cases of combined schwannomas and neurofibromas (and even perineuriomas) have been described, though their incidence is not known. Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors typically present with a mass lesion and mild to moderate paresthesias or dysesthesias. Motor examination is typically normal.

Significant overlap exists in the MRI appearance of schwannomas and neurofibromas. The classic MRI appearance of a schwannoma is an eccentrically placed round intraneural mass with well-defined smooth borders (Fig. 41.2). The parent nerve may be seen at the proximal and distal margins of the mass. The “split fat sign” refers to a thin rim of fat about the mass, best seen on T1-weighted images, indicating the mass is arising in an intermuscular location. T1-weighted signal ranges from isointense to skeletal muscle to slightly hyper-intense and T2-weighted images classically demonstrate a “target sign” with T2-hyperintensity and relative decreased signal centrally. Conventional schwannomas demonstrate diffuse homogeneous enhancement on postgadolinium images; however, the signal characteristics are variable and range from solid and homogeneous to cystic. On PET, approximately one third of schwannomas have avid uptake. Neurofibromas are more classically fusiform lesions and less likely to be cystic, but the remainder of the MRI findings are similar to those of schwannomas. Both schwannomas and neurofibromas may produce plexiform lesions, the latter commonly involving the proximal peripheral nerve. In some cases, patients may have extensive plexiform lesions assuming a lobulated appearance; these patients may have mild or moderate neurologic deficit. The differential diagnosis of plexiform nerve sheath tumor includes other hypertrophic neuropathies such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Plexiform neurofibromas tend to demonstrate marked enhancement on postgadolinium images that help distinguish them from other hypertrophic neuropathies.

• Sporadic nerve sheath tumors typically present as schwannomas. Syndromic nerve sheath tumors associated with NF1 are often neurofibromas, and those associated with NF2 or schwannomatosis are often schwannomas.

Treatment

Surgery is performed for several reasons. It best treats patients’ symptoms, eliminates the tumor, and decreases the need or interval for follow-up examinations. Surgery tends to be easier and safer when tumors are smaller. Tumors tend to grow over a patient’s lifetime, but this is not always the case. Thus, the life expectancy of a patient needs to be considered. Surgical resection provides definitive tissue diagnosis. There is also a small risk (5–10%) that neurofibromas can transform into a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST); the risk of a schwannoma transforming is nearly nil.

In cases of benign peripheral nerve tumors, the aim of surgical resection is to save the nerve and preserve neural function, which can be achieved in 80 to 90% of patients. Outcomes are slightly better for patients with schwannomas than for patients with neurofibromas. Patients with larger tumors (> 5 cm) and previous surgery (or even open biopsy) have less favorable outcomes. Recurrence after gross total resection is low (1 to 2%). A standardized approach can be utilized to maximize good results.4 Surgical exposure is generous enough to allow proximal and distal control of the affected nerve.

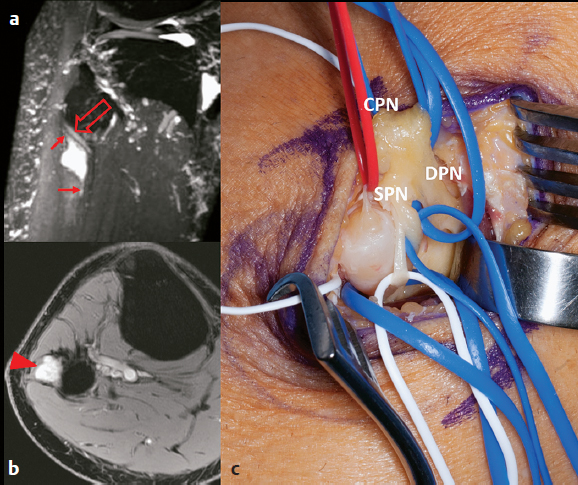

Fig. 41.2a–c Schwannoma of the superficial peroneal nerve at the fibular neck. This patient presented with focal chronic pain near the lateral knee without any neurologic deficit. (a) Sagittal oblique maximum intensity projection from a three-dimensional T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence demonstrates a hyperintense mass in the superficial peroneal nerve with superior and inferior “tails” (arrows). There is mass effect on the deep peroneal nerve (open arrow). (b) The mass demonstrates intense postgadolinium enhancement (arrowhead) on this axial postgadolinium fat-saturated image. (c) At operation, the schwannoma of the superficial peroneal nerve (SPN) is removed. The single entering fascicle (seen in a red vasoloop) of the SPN schwannoma has been identified, having been dissected away from the main SPN and two SPN en passant fascicles (in white vasoloops). The common peroneal nerve (CPN) and the deep peroneal nerve (DPN) have been mobilized in blue vasoloops.

The temptation to concentrate on the tumor itself from the start should be avoided. Neighboring nerves and vessels at risk should first be identified and protected prior to attempting the tumor resection. Vasoloops help mobilize the nerve(s). The nerves and the tumor should be carefully mobilized in a 360-degree fashion. The nerve can then be rolled so that the nerve (fascicles) can be mapped on the tumor surface either with direct visualization or with a disposable stimulator. Schwannomas are typically eccentric tumors, whereas neurofibromas are often more centrally located. A bare area where the tumor is seen without intervening fascicles is identified. A longitudinal epineurotomy is performed in the tumor capsule, and the pseudocapsule around the tumor is maintained. Using blunt dissection techniques, the entering and exiting fascicle(s) can be identified. These fascicles, if tested, do not produce muscle contraction. All of the other fascicles are preserved in the outer shell of the tumor capsule and swept to the sides. The tumor can be rolled out. Resecting the entering or exiting fascicle can help mobilize the larger tumors. Sharp dissection should be delayed as long as possible (Fig. 41.2). Occasionally, larger tumors are removed in a piecemeal fashion or drained of cystic contents. This facilitates the dissection. Plexiform (multifascicular) lesions must be treated with caution (see Syndromes, below).5

• When removing benign peripheral nerve tumors, it is critical to identify and protect neighboring nerves and vessels before beginning resection of the tumor itself.

Syndromes

Syndromes

More detailed discussion of NF1, NF2, and schwannomatosis is presented in standard neurooncology textbooks. However, it is important to note that peripheral nerve tumors are often part of syndromes. The peripheral nerve tumors may be identified only as part of routine testing in patients with other central nervous system (CNS) lesions. Alternatively, the syndrome may be diagnosed only after several peripheral nerve lesions have been found.

Pattern

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree