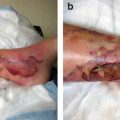

Fig. 14.1

Computed tomography scan of a 13-year-old patient presenting with persistent malaise, fever, and weakness. Decreased sensorium developed in the child while awaiting evaluation in an EC. His white blood cell count exceeded 400,000/mL. The scan revealed multifocal cerebral hemorrhages with associated edema leading to clinical brain death several days later

The most common sign of brain tumors at presentation is headache. Classic tumor-related headaches last for several days to weeks, may cause sleep disturbances, are accompanied by nausea and vomiting, and increase in severity with straining or coughing. Headaches may be poorly localized, although some children with posterior fossa tumors may describe having headaches at occipital locations. Developmental delay or regression may occur in infants and toddlers. School-aged children may experience changes in their academic performance. Cranial nerve dysfunction and balance problems may be noted in children with brainstem or posterior fossa tumors. Seizures and decreased levels of consciousness may be presenting complaints, as well. Nonspecific symptoms such as poor appetite, subtle behavior changes, and nonlocalizing pain may be vague and persist for some time, usually a few weeks, occasionally prompting evaluation for gastrointestinal problems.

Management Principles

Shock may be evident in a pediatric patient upon admission to the EC. More often, however, early hemodynamic dysfunction and compensated shock are missed because children tend to have high resting heart rates and systemic vascular resistance and thus may have normal or even high blood pressure in the presence of hypovolemia and shock. Narrow pulse pressure (the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) suggests hypovolemia or other causes of reduced stroke volume, whereas low diastolic pressure suggests inappropriately low systemic vascular resistance, most commonly because of sepsis. Hypovolemia manifested by tachycardia, tachypnea, narrow pulse pressure, cool extremities, and decreased mentation and urine output may be caused by dehydration resulting from intestinal loss, diabetes insipidus, or overt or occult hemorrhage.

Children with cardiogenic shock caused by sepsis or acquired cardiomyopathy usually have tachypnea with rales and may have jugular venous engorgement, a third heart sound, or hepatomegaly. Children with distributive shock caused by sepsis or, less often, anaphylaxis have tachycardia with a flushed appearance, low diastolic blood pressure, and evidence of end-organ dysfunction. Obstructive shock may result from tumors impinging on mediastinal vascular structures. These patients may experience cardiac arrest with absolute or relative hypovolemia, underscoring the need to provide them with adequate fluid resuscitation with isotonic crystalloids, colloids, or indicated blood products and avoid indiscriminate use of sedative agents.

Seizures

Children with obvious or suspected seizure activity at presentation should be presumed to have status epilepticus. High-flow oxygen, assessment of airway patency, and vascular access are priorities for these patients. Hypoglycemia should be excluded by performing a bedside test within the first few minutes of presentation. Seizures may be controlled with the use of benzodiazepines and first-line antiepileptic drugs such as fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, and valproic acid. Phenobarbital must be used with extreme caution as it commonly causes respiratory depression.

Decreased Level of Consciousness

Children with decreased levels of consciousness should be presumed to have increased intracranial pressure until proven otherwise. Ensuring that their ventilation and hemodynamics are adequate is essential for maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion. Hypovolemia and hypotension should be immediately corrected. Unstable patients or those with declining vital signs are at imminent risk for cardiopulmonary arrest, and Pediatric Advanced Life Support protocols should be activated.

Originally developed for assessment of traumatic brain injury, the Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale has proven to be reliable in assessing mental status in the general pediatric population (Table 14.1). Patients with declining Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale scores should undergo intubation prior to computed tomography or other diagnostic testing. A score at or near 8 indicates the need to secure the airway after administration of lidocaine and analgesics and sedation. Three percent hypertonic saline may be superior to mannitol in that it aids maintenance of intravascular space while helping to correct increased intracranial pressure, particularly in the presence of hyponatremia. Dexamethasone should be administered to any patient with features suggestive of a space-occupying intracranial mass. Urgent neurosurgical consultation is mandatory for possible cerebrospinal fluid diversion or shunting.

Table 14.1

Pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale

Eye opening | |

Spontaneous | 4 |

Speech | 3 |

Pain | 2 |

None | 1 |

Verbal response | |

Coos, babbles | 5 |

Irritable cries | 4 |

Cries to pain | 3 |

Moans to pain | 2 |

None | 1 |

Motor response | |

Normal spontaneous movement | 6 |

Withdrawn to touch | 5 |

Withdrawn to pain | 4 |

Abnormal flexion | 3 |

Abnormal extension | 2 |

None | 1 |

Spinal Cord Compression

Spinal cord compression may complicate a variety of malignancies but occurs most often in children with solid tumors such as osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma . Any complaints of backache, especially when accompanied by weakness or neurologic deficits, should be managed expeditiously with neurosurgical consultation, magnetic resonance imaging, and administration of high-dose steroids. Analgesia may be safely provided with carefully titrated doses of opioids. Hypotension or hypovolemia must be avoided to minimize the possibility of secondary spinal cord injury. Any delays in definitive therapy for spinal cord compression may result in permanent deficits.

Respiratory Distress

Any child who presents with respiratory distress is at risk for rapid progression to respiratory failure. Tachypnea may accompany sepsis, hypovolemia, and severe anemia and may be easily missed given the increased resting respiratory rate common in children. Refusal of a patient to adopt a supine position may indicate the presence of a mediastinal mass impinging the airway and must always be managed with great caution, avoiding sedation and positioning that may precipitate respiratory arrest. Stridor may respond to the use of nebulized racemic epinephrine while the patient is awaiting otolaryngologic consultation. Children with small airway disease, marked by expiratory wheezing, may benefit from nebulization with levalbuterol. Children with known or suspected myocardial dysfunction may present with pulmonary edema, which may be mitigated by administration of loop diuretics at carefully titrated doses.

All patients who present with these features merit very close observation, as subtle abnormalities can quickly culminate in overt respiratory failure and life-threatening tissue hypoxia. Children, particularly small infants, tolerate these challenges poorly because of their small collapsible airways; compliant thoraces with immature, easily fatigued muscles; and limited functional residual capacity. A significant fraction of cardiac output may be diverted when breathing effort is increased, underscoring the importance of timely ventilator support in critically ill children.

Acute lung injury may be indicated by progressive increases in work of breathing with hypoxemia unresponsive to delivery of supplemental oxygen via a simple face mask at presentation. Children with respiratory distress should be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for consideration of assisted ventilation.

Intubation for respiratory failure of any etiology is greatly facilitated by proper preparation. Acutely ill children commonly have delayed gastric emptying. Therefore, they should be considered to have full stomachs and intubated using appropriate precautions. Cuffed endotracheal tubes are preferred for all children to maintain mean airway pressure and recruit small airways. In the absence of overt pulmonary edema and cardiac failure, most children benefit from receiving a crystalloid or colloid bolus to ensure optimal intravascular volume. Correction of thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy is desirable prior to intubation to minimize bleeding, which may obscure the airway.

Treatment with atropine minimizes airway secretions while preventing potentially devastating vagally mediated bradycardia and thus should be considered for all patients, particularly young infants. Ketamine is a valuable agent because of its profound analgesic and amnestic effects as it does not cause the hemodynamic instability that opioids (particularly morphine), propofol, and benzodiazepines can promote. The use of etomidate in a hemodynamically unstable child is discouraged except when increased intracranial pressure is strongly suspected, as it may cause adrenal insufficiency and has been associated with increased mortality rates in some studies.

Optimal tidal volumes generally range from 6 to 8 mL/kg ideal body weight, with inspiration times and frequencies titrated to ensure adequate ventilation while minimizing dynamic hyperinflation. High peak airway pressures and low end-expiratory pressures should be avoided during arrangement of a transfer of a patient to an ICU. Adequate analgesia, sedation, and neuromuscular blockade must be used as indicated to prevent displacement of the endotracheal tube.

Febrile Neutropenia and Sepsis

Febrile neutropenia is perhaps the most common complication of chemotherapy. Although the majority of children who have it can be integrated into comprehensive general care unit-based protocols targeting the most common gram-positive and -negative pathogens (including viridans streptococci, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa), some children present with evidence of a systemic inflammatory response and compensated shock, with tachycardia, vasomotor tone abnormalities, and impaired perfusion, which is manifested as subtle changes in behavior or consciousness level or decreased urine output before progression to septic shock.

Prompt, accurate assessment of a child’s hemodynamics with indicated resuscitative measures, including timely (within the first few minutes after presentation) administration of appropriate antimicrobials having broad-spectrum coverage such as cefepime and vancomycin, is essential for a successful outcome. Children differ from adults in that they typically need large amounts of isotonic crystalloid to repair relative and absolute hypovolemia, tend to present with or experience hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia, have a propensity for development of respiratory failure, and experience late preterminal development of hypotension. Delays in the recognition and appropriate management of the shock state cause proportional increases in morbidity and mortality rates in children. Conversely, optimal management in accordance with published guidelines improves clinical outcomes as assessed in a variety of hospital settings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree