Highlights

- •

Spanish-speaking Hispanic men had no long-term adverse outcomes despite lower SES.

- •

English-speaking Hispanic men reported higher levels of treatment-related regret.

- •

Spanish surveys may reflect language concordant care, improving outcomes.

- •

Findings highlight the need for language-sensitive, personalized PCa survivor care.

Abstract

Objectives

Compare functional outcomes and treatment-related regret over 10 years in Spanish- and English-speaking Hispanic men compared to non-Hispanic men following treatment of localized prostate cancer.

Methods and Materials

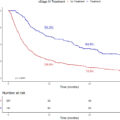

Data from a prospective cohort study of men with localized prostate cancer treated with active surveillance, radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy were used to examine the effect of survey language (Spanish speaking vs. English speaking) and ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic) on functional outcomes and treatment-related regret over 10 years. Outcomes were measured using validated questionaries adjusting for baseline patient and disease characteristics.

Results

A total of 770 men were included, 12% were Spanish-speaking and 12% were English-speaking Hispanic men. Compared to non-Hispanic men, Spanish-speaking Hispanic men had clinically meaningfully better urinary incontinence scores at years 3, 5 and 10 (adjusted mean difference [aMD], 12.4, 95% CI, 4.8 to 20.0; at year 10), as well as better bowel function scores at 10 years (aMD, 5.1, 95% CI 2.3 to 8.0). English-speaking Hispanic men had clinically worse urinary incontinence at 3 and 5 years (aMD, -10.7 [95% CI, -17.6 to -3.9]; at year 5) and bowel function at 10 years (aMD, -4.3 [95% CI, -8.2 to -0.4]) compared to Spanish-speaking Hispanic men. English-speaking Hispanic men were more likely to report regret than Spanish-speaking Hispanic men at 10 years (adjusted odds ratio, 7.9, 95% CI, 1.3–46.2).

Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of considering language and ethnicity when providing counseling and support for prostate cancer survivors, emphasizing the need for personalized patient-centered care.

1

Introduction

Hispanic people are the most rapidly growing ethnic/racial group in the US, numbering more than 62.1 million in 2020 [ ]. Among US Hispanic males, prostate cancer (PCa) is the most diagnosed cancer, accounting for more than 25% of all new cancer cases, and is the leading cause of cancer death [ ]. Disparities in PCa care among Hispanic populations compared to non-Hispanic white men include lower screening rates, limited access to adequate care, and inadequate patient-provider communication, contributing to inferior oncologic outcomes [ , ]. More generally, lower quality of healthcare, resulting in worse health outcomes and lower satisfaction after treatment, is more likely when language barriers exist between providers and patients, independent of insurance and socioeconomic status among Hispanic people [ , ]. Furthermore, cultural factors beyond language—such as mistrust of the healthcare system, stigma, gender roles, religious beliefs, and fears related to prostate cancer—have been shown to affect outcomes in populations with limited English proficiency [ , ].

Cancer survivorship encompasses the impact of cancer and its treatment on various aspects of life, including self-perception, relationships, long-term side effects and satisfaction with care [ ]. A crucial aspect of survivorship after localized PCa treatment is functional outcomes (i.e., urinary, sexual, and bowel function, and hormone therapy side effects). Moreover, treatment-related regret has emerged as a valuable, patient-centered outcome in PCa survivorship, as it captures treatment-related morbidity, oncologic outcomes, and anxiety through a patient’s own lens [ , ]. While patient-reported functional outcomes and treatment-related regret following treatment have been studied in white and Black men, data on Hispanic men are lacking [ , ]. As such, our study aimed to explore variation in post-treatment functional outcomes and treatment-related regret over a 10-year period among Spanish-speaking Hispanic men, comparing them to English-speaking Hispanic men and non-Hispanic men.

2

Methods and methods

2.1

Cohort and Study population

Participants from the prospective population-based Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation study (CEASAR) study were recruited from 5 population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries (Atlanta, Georgia; Los Angeles, California; Louisiana; New Jersey; and Utah) from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012. For this study, we restricted the cohort to the Los Angeles (LA) registry (n=770) because surveys in Spanish were only offered at this site. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from each participating site and from the coordinating center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

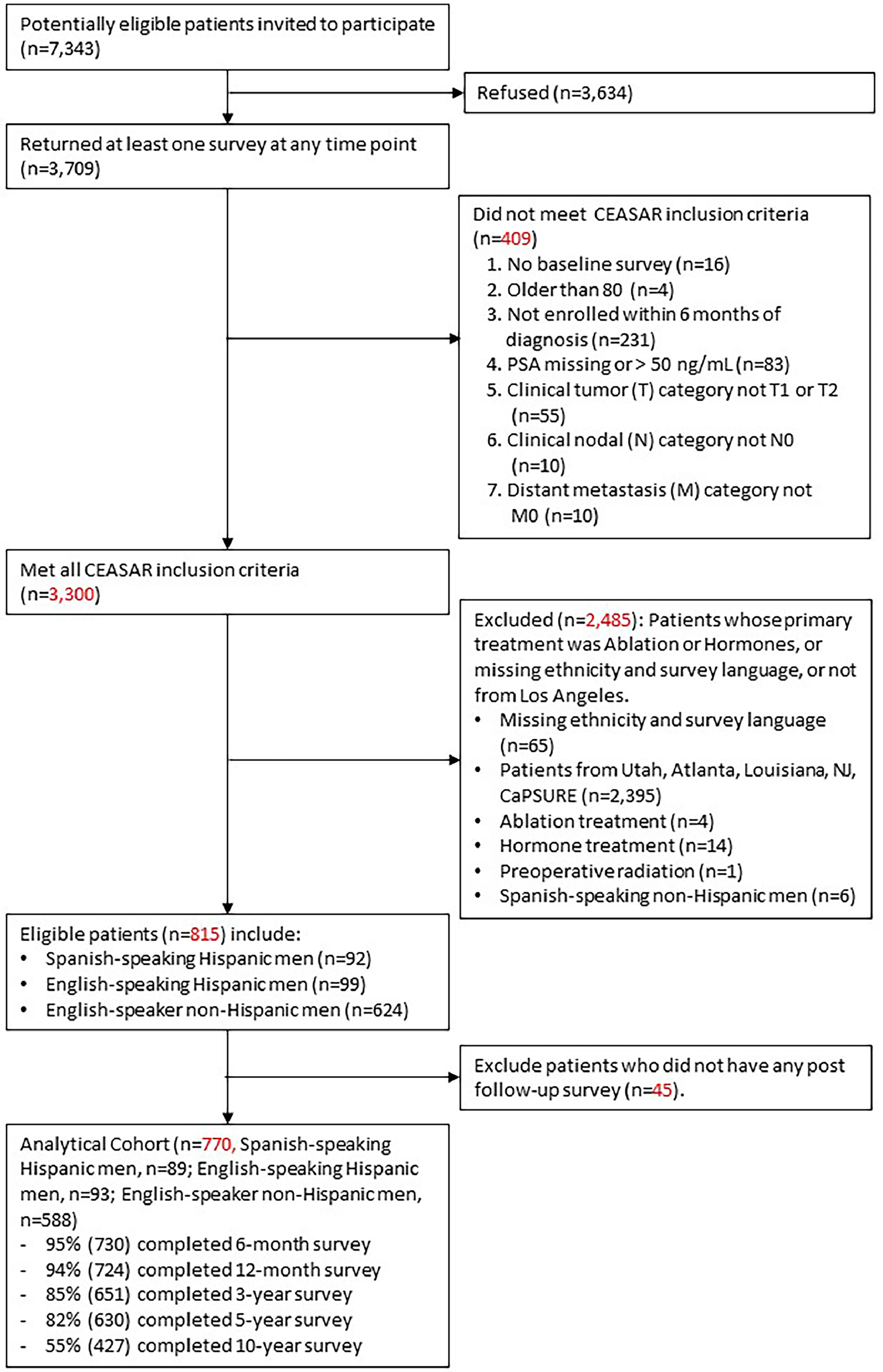

The CEASAR study included men aged ≤ 80 years old at diagnosis with clinically localized PCa (cT1-cT2, cN0, cM0), a prostate-specific antigen level of less than 50 ng/mL, and enrollment within 6 months of diagnosis. We included men whose primary treatment was active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy and excluded other primary therapies to limit our analysis to the most common and guideline-recommended treatments ( Figure 1 ).

Data collection involved patient-reported surveys and medical chart abstraction. Mailed surveys were completed at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 3 years, 5 years, and 10 years after enrollment. If there was no response after 2 mailings, the survey was completed via telephone interview administered by a trained research staff member. surveys were translated into Spanish at the outset of the study, allowing participants to complete them in either Spanish or English. We employed the Spanish version of the EPIC-26, which has been validated as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing the impact of various treatments on patients with localized prostate cancer [ ]. Additional sections of the surveys were translated by a professional translating company, and these translations were reviewed by native Spanish speakers from the Department of Population and Public Health Sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California. Any recommended changes were discussed with the translating company to ensure accuracy and cultural relevance.

Ethnicity was classified as non-Hispanic or Hispanic according to patient-reported data; if unavailable, information from the SEER registry was used. Hispanic men were classified as Spanish-speaking if they completed any surveys in Spanish, serving as a surrogate for determining their primary language. This approach allowed us to assess language preference indirectly. Patient-reported data were supplemented with medical chart abstraction at 1 and 10 years after enrollment. we ascertained primary language by whether the participant filled out surveys in Spanish, rather than directly inquiring about their language preference.

2.2

Exposure

The main exposure variables were survey language (Spanish speaking vs. English-speaking) and ethnicity (Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic). There were 3 distinct groups of interest: Spanish-speaking Hispanic men, English-speaking Hispanic men, and English-speaking non-Hispanic men. To examine the association between language and the outcomes of interest within the Hispanic population, we compared Spanish-speaking Hispanic men to English-speaking Hispanic men. This comparison addressed the association between language (English vs. Spanish) and outcomes among Hispanic individuals. To examine the association between ethnicity and the outcomes of interest within the English-speaking population, we compared English-speaking Hispanic men to English-speaking non-Hispanic men. This comparison examined the influence of ethnicity (Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic) within the English-speaking subgroup.

2.3

Outcomes

We evaluated patient-reported disease-specific function using the validated 26-item Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC-26). Each functional domain was scored 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function [ ]. Differences were interpreted as clinically meaningful if they were greater than the following previously published minimum clinically important differences (MCIDs) for each EPIC domain: sexual function, 10–12; urinary incontinence, 6–9; urinary irritative, 5–7; bowel function, 4–6; and hormonal function, 4–6 [ ].

Our secondary outcome of interest was treatment-related regret, assessed at 3-, 5-, and 10 years after treatment using a validated scale [ ] categorizing patients as having significant regret where scores were 40 or greater [ ].

2.4

Statistical analysis

Participants’ demographic, clinical and disease characteristics expressed as categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages and compared among groups using χ2 tests. Continuous variables were summarized using median values and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) and compared among the 3 groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Unadjusted EPIC-26 domain scores in each group were graphed according to time since treatment. The curves were based on the fitted values obtained from longitudinal linear regression models that included time since treatment, language/ethnicity groups and their interaction terms. Restricted cubic spline with 5 knots was used for time since treatment to allow nonlinear associations with the outcomes. Multivariable longitudinal linear regression was used for the primary outcomes, and multivariable logistic regression models were used for the secondary outcome. For the longitudinal model, generalized estimating equations were used with the Huber-White method to estimate the robust covariance matrix to account for the correlation among records from the same man. The following variables were included in all multivariable models: 3-tier exposure group, treatment (Surgery, Radiation, Active Surveillance), age (continuous), education (High school graduate and less, Some college and above), comorbidity measured by Total Illness Burden Index for Prostate Cancer (0–2, 3–4, ≥5), D’Amico risk group (low, intermediate, high), any ADT within 1 year (yes, no), a participatory decision-making scale (PDM7) at baseline (continuous), healthcare engagement/passivity measured with the Provider-dependent Health Care Orientation scale (PDHCO6) at baseline (continuous), time since treatment (continuous), and corresponding baseline EPIC domain scores (continuous) [ , ]. Restricted cubic splines with 3 knots were used to allow nonlinear associations with the outcomes for age, time since treatment, and baseline domain scores. Interaction terms of treatment and time since treatment and of comparison group and time since treatment were included in longitudinal models. Missing covariates were imputed using the multiple imputation using chained equations. No outcome variables were imputed. Analyses were performed using R version 4.1. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3

Results

3.1

Baseline characteristics

Among 770 men in the Los Angeles CEASAR cohort, 89 (12%) were Spanish-speaking Hispanic men, 93 (12%) were English-speaking Hispanic men, and 588 (76%) were Non-Hispanic men. There were no statistically significant differences in PCa risk group at time of diagnosis or in treatment approach selected between groups ( Table 1 ). Spanish-speaking Hispanic men less frequently had an education beyond high school (10% for Spanish-speaking men vs. 40% for English-speaking Hispanic men vs. 80% for non-Hispanic men) and an income above $50,000 (94% for Spanish-speaking men vs. 66% for English-speaking Hispanic men vs. 36% for non-Hispanic men) and reported lower levels of engagement in participatory decision-making than English-speaking Hispanic or non-Hispanic men (P < 0.006).

| Hispanic Men | English -Speaking Non-Hispanic N=588 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish-Speaking Hispanic N=89 | English-Speaking Hispanic N=93 | |||

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 63 (58, 68) | 64 (57, 70) | 65 (59, 70) | 0.27 |

| Income, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≤$50,000 | 72 (94%) | 52 (66%) | 188 (36%) | |

| >$50,000 | 5 (6%) | 27 (34%) | 332 (64%) | |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than and equal to high school | 75 (90%) | 52 (60%) | 109 (20%) | |

| Some college and above | 8 (10%) | 34 (40%) | 449 (80%) | |

| Employment, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Full time | 33 (38%) | 31 (33%) | 257 (44%) | |

| Part time | 7 (8%) | 4 (4%) | 56 (10%) | |

| Retired | 29 (33%) | 46 (49%) | 244 (42%) | |

| Unemployed | 18 (21%) | 12 (13%) | 28 (5%) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | 0.17 | |||

| Not married | 15 (18%) | 26 (30%) | 151 (27%) | |

| Married | 67 (82%) | 60 (70%) | 405 (73%) | |

| Comorbidity score (TIBI), n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| 0-2 | 42 (49%) | 38 (44%) | 168 (30%) | |

| 3-4 | 29 (34%) | 30 (35%) | 229 (41%) | |

| 5 or more | 14 (16%) | 18 (21%) | 162 (29%) | |

| TUMOR AND TREATMENT CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Clinical Tumor stage, n (%) | 0.93 | |||

| T1 | 75 (84%) | 79 (85%) | 489 (83%) | |

| T2 | 14 (16%) | 14 (15%) | 97 (17%) | |

| Biopsy Gleason Score, n (%) | 0.27 | |||

| 6 or less | 51 (58%) | 49 (53%) | 315 (54%) | |

| 3+4 | 17 (19%) | 22 (24%) | 164 (28%) | |

| 4+3 | 7 (8%) | 13 (14%) | 50 (9%) | |

| 8,9,10 | 13 (15%) | 9 (10%) | 56 (10%) | |

| Damico risk group, n (%) | 0.52 | |||

| Low risk | 44 (50%) | 43 (46%) | 353 (46%) | |

| Intermediate risk | 27 (31%) | 38 (41%) | 295 (38%) | |

| High risk | 17 (9%) | 12 (13%) | 119 (16%) | |

| Treatment, n (%) | 0.1 | |||

| Surgery | 49 (55%) | 62 (67%) | 338 (57%) | |

| Radiation | 29 (33%) | 19 (20%) | 139 (24%) | |

| Active Surveillance | 11 (12%) | 12 (13%) | 111 (19%) | |

| Use of ADT within 1 year of diagnosis, n (%) | 0.056 | |||

| Yes | 19 (22%) | 14 (16%) | 71 (12%) | |

| No | 68 (78%) | 74 (84%) | 497 (88%) | |

| Nerve-Sparing Surgery, n (%) | 0.74 | |||

| Bilateral nerve-sparing | 27 (87%) | 35 (85%) | 217 (89%) | |

| None or unilateral nerve-sparing | 4 (13%) | 6 (15%) | 26 (11%) | |

| Participatory Decision-Making (PDM7), median (quartiles) | 0.006 | |||

| 71 (47, 90) | 79 (54, 89) | 82 (65, 93) | ||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree