Hyperplasia(typical)

Simple hyperplasia without atypia

Complex hyperplasia without atypia

Atypical hyperplasia

Simple atypical hyperplasia

Complex atypical hyperplasia

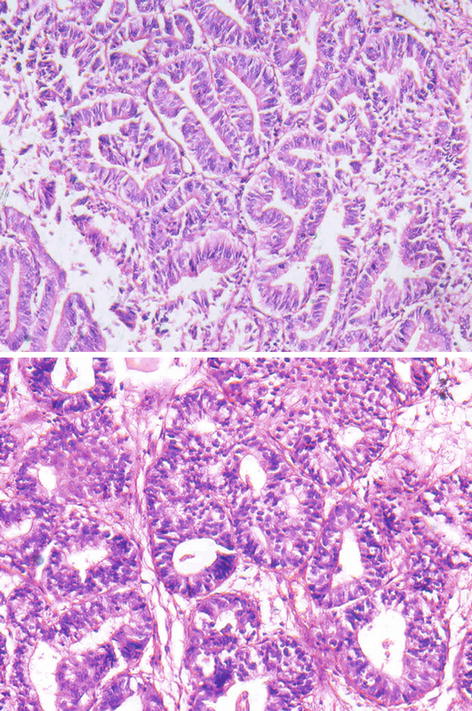

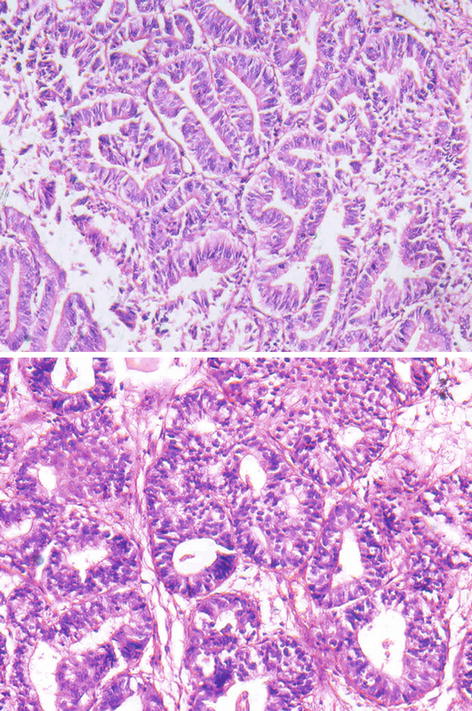

Fig. 4.1

Endometrium – simple hyperplasia

Pathophysiology

Oestrogen replacement therapy has been shown to have a strong association with the development of endometrial carcinoma, and the factors which decrease the exposure of the endometrium to oestrogen have decreased the risk of endometrial carcinoma including the addition of progestin to oestrogen replacement therapy [4, 5]. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia has been associated with a number of genetic alterations including mutation in the PTEN tumour suppressor gene and KRAS oncogene and microsatellite instability [6]. These are the most common genetic alterations in endometrioid carcinoma, which support atypical hyperplasia as a precursor lesion.

Endometrial carcinoma

Definition

Endometrial carcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumour, arising in the endometrium with glandular differentiation, but it may have variable morphology.

Pathophysiology of Endometrial Carcinoma

A number of studies have demonstrated the association of oestrogen with the development of endometrial carcinoma. Exogenous oestrogen without progesterone has been associated with increased adenocarcinoma. The excess risk can be significantly reduced by the concomitant administration of progestins [4, 5]. There has been a conflicting data on the risk of endometrial cancer with the use of tamoxifen [7]. Obesity has been a well-defined risk factor too, due to increased availability of oestrogen as a result of aromatization of androgens in the adipose tissue [8]. Prolonged exposure to oestrogen due to chronic anovulation in nullipara, late menopause and early menarche may be related to increased risk [9].

Endometrial carcinoma can be divided into two categories based on clinicopathologic and molecular genetic features referred to as type I and type II. Type I is associated with unopposed oestrogen stimulation and is often accompanied by atypical hyperplasia. It is usually a low-grade carcinoma of favourable prognosis and more commonly occurs in perimenopausal white women. Type II has no association with exogenous oestrogen or endometrial hyperplasia. It is usually high grade and has an unfavourable prognosis and occurs in postmenopausal women, often of African-American or Asian descent [4, 5, 10–12].

Macroscopy

Endometrial carcinoma presents as an exophytic mass, usually seen in an enlarged uterus, or the tumour presents as a diffuse thickening of the endometrium with a shaggy, glistening and tan surface and presents more frequently on the posterior than on the anterior wall [13]. The tumour may be focal, at times presenting as polypoidal mass. Myometrial invasion usually appears as firm grey-white area in the form of linear extensions. The tumour may penetrate the serosa, and extension into the cervix is common.

Microscopy

Endometrial carcinoma has various histological types based on the cell morphology (Table 4.2).

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma |

Variant with squamous differentiation |

Villoglandular variant |

Secretory variant |

Ciliated cell variant |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

Serous adenocarcinoma |

Clear cell adenocarcinoma |

Mixed cell adenocarcinoma |

Squamous cell carcinoma |

Transitional cell carcinoma |

Small cell carcinoma |

Undifferentiated carcinoma |

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma is the most common type accounting for almost three-fourths of the cases [11]. It resembles a proliferative phase endometrium with small, back-to-back glands without the stroma intervening. The grade of the tumour is based on nuclear features and architectural pattern. The nuclear grade is determined by the variation in nuclear size and shape, nucleoli and distribution of chromatin. The architecture grade and pattern are seen as how well the gland formation is seen as compared to solid clusters of tumour cells. Glandular complexity may be seen as luminal budding, papillae and cribriform patterns. Mitotic activity usually increases with the increase in nuclear grade and is an independent variable. The grading of the tumour is done according to the degree of gland formation by the tumour (Table 4.3). In grade 1 lesions, nuclei of the lining epithelial cells are uniform with minimal atypia and small discrete nucleoli (Fig. 4.2). The degree of tumour necrosis is usually mild to moderate. Marked amount of necrosis is unusual, even in high-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4.3).

Grade 1 | Less than 5 % of solid areas (excludes squamous differentiation) |

Grade 2 | 6–50 % solid areas |

Grade 3 | More than 50 % solid areas |

Fig. 4.2

Photomicrograph of endometrioid adenocarcinoma – grade 1

Fig. 4.3

Photomicrograph of endometrioid adenocarcinoma – grade 3 (high grade)

Variants

Different morphologic patterns of endometrioid adenocarcinoma are seen including villoglandular, secretory, ciliated cell and adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. These patients share similar epidemiologic characteristics of typical endometrioid carcinoma, and these patterns may be seen in association with the usual form of endometrioid cell type.

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma with Squamous Differentiation

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma may contain squamous epithelium. The proportion of squamous element can be variable. At least 10 % of the tumour should have a squamous element in a well-sampled tumour to qualify as endometrioid carcinoma with squamous differentiation. There are no differences in clinical features of this variant. It is graded on the basis of glandular component of the tumour as well, moderately or poorly differentiated. The treatment of this variant is the same as for endometrioid carcinoma of comparable stage.

Villoglandular Carcinoma

This variant displays papillary architecture with cells resembling usual endometrioid carcinoma. The papillary fronds comprise delicate fibrovascular cores covered by columnar cells with oval nuclei that generally show mild to moderate nuclear atypia. Occasionally high-grade nuclear atypia is seen where one has to differentiate it from serous carcinoma as both have distinct papillary pattern. Mitosis is variable and myometrial invasion is usually superficial.

Secretory Carcinoma

This variant appears histologically similar to secretory phase endometrium with columnar cells that have abundant vacuolated cytoplasm. They may have a cribriform or villoglandular pattern. Glands are back to back with presence of stromal invasion. Cellular atypia is minimal. The neoplasm is of low grade, and the prognosis is good. It is important to differentiate it from clear cell carcinoma.

Ciliated Cell Carcinoma

This is a rare variant of endometrioid carcinoma. Ciliated cells may be seen occasionally in endometrioid adenocarcinoma, but the majority of the malignant glands should be lined by ciliated cells to categorise it as this variant. One has to be just careful that endometrial proliferations with cilia may be carcinomatous too.

Mucinous Carcinoma

Mucinous carcinoma is an adenocarcinoma with abundant intracellular mucin. To categorise it as mucinous carcinoma, more than 50 % of the cell population must contain mucin which should be PAS positive and diastase resistant. Its appearance is similar to the mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma, and it has to be differentiated from the clear cell carcinoma where the pattern is usually papillary or solid as compared to glandular in this variant. Endometrioid and clear cell adenocarcinoma may have large amounts of intraluminal mucin, but only mucinous adenocarcinoma contains the mucin within the cytoplasm. They tend to be of low grade with a good prognosis.

Serous Carcinoma

Serous carcinoma usually involves older women and is uncommon as compared to endometrioid carcinoma. It often displays papillary architecture like the variants of endometrioid carcinoma, but the papillae here have broad cores, and the pattern may be even solid. The cytologic atypia is marked (Fig. 4.4). Psammoma bodies may be present. These tumours are aggressive and have a poor prognosis. They are considered as high-grade neoplasms and are not graded. These tumours have a predilection for peritoneal spread, akin to ovarian serous adenocarcinoma [15].