Fig. 3.1

Penile anatomy. (a) Anatomical compartments: 1 is glans, 2 is foreskin, and 3 represents coronal sulcus. (b) Anatomical levels in the glans are EP (epithelium), LP (lamina propria), CS (corpus spongiosum), CC (corpus cavernosum), and TA (tunica albuginea). Foreskin levels are EP, LP, DM (dartos muscle), and SK (skin)

There is a correlation of tumor depth or thickness and prognosis [3]. The TNM staging system is based on the extent of tumor invasion into anatomical levels [1]. It is important for the pathologist to be familiar with penile anatomical levels. They are in the glans, squamous epithelium, lamina propria (LP), corpus spongiosum (CS), and corpora cavernosa (CC). The latter are subdivided by the tunica albuginea, which is considered part of the corpus cavernosum. In the foreskin, the levels are squamous epithelium, lamina propria, dartos muscle, and outer skin (Fig. 3.1b) [4, 5]. Anatomical levels for coronal sulcus tumors are not well established, considering the rarity of tumors originating at this site [5]. For the evaluation of resection margins, anatomical sites commonly involved by carcinoma should be identified. In one study, the most common site was demonstrated to be the penile urethral margin with its underlying lamina propria and surrounding corpus spongiosum, penile (Buck) fascia, and skin of shaft (Fig. 3.2) [6]. There is some criticism of the current pathological TNM staging system. Currently, a T2 is given to tumors invading either corpus spongiosum or corpus cavernosum. We and others think that tumor invasion of each anatomical level, CS and CC, should be given a different T, considering the variable prognosis of tumors in each invasion category [7–9].

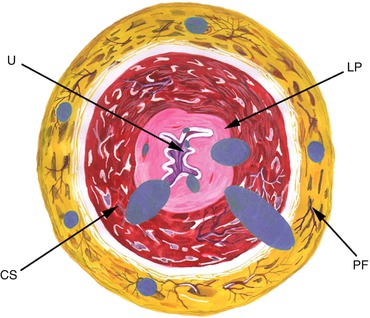

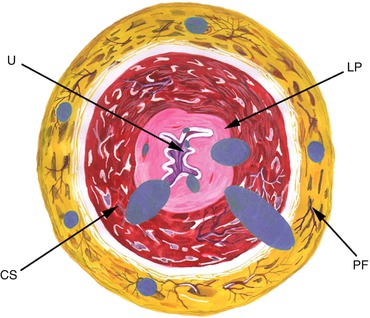

Fig. 3.2

Positive surgical margins. Frequent sites of tumor involvement in urethral and periurethral tissues. Each blue dot represents the affected site in a different patient. Urethral epithelium and penile fascia are the most commonly involved anatomical sites in the urethra. U urethra, LP lamina propria, CS corpus spongiosum, PF penile fascia

Subtypes of Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinomas

About half of penile neoplasms are conventional squamous cell carcinomas (Usual SCCs). There are, however, various subtypes with distinct clinical, morphological, and outcome features (Table 3.1) [2, 10]. Well known is the verrucous carcinoma (Fig. 3.3a), recognized in the oral mucosa by Dr. Lauren Ackerman [11]. They are exophytic verruciform tumors which on cut surface show a white tumor with a distinct broad base separating it from the stroma [12]. Microscopically, they are papillomatous, acanthotic, keratinizing, and extremely differentiated neoplasms. There are three pathological variants, the classical or pure, by definition noninvasive; the microinvasive (in lamina propria), both without metastatic potential; and the mixed or hybrid, with metastatic potential in up to 20–25 % of the cases [2].

Table 3.1

Pathological classification of invasive SCCs

Frequent subtypes | Rare subtypes |

|---|---|

Usual SCC | Carcinoma cuniculatum |

Verrucous carcinoma | Papillary-basaloid carcinoma |

Basaloid carcinoma | Sarcomatoid carcinoma |

Warty (condylomatous) carcinoma | Pseudohyperplastic carcinoma |

Papillary carcinoma | Pseudoglandular carcinoma |

Warty-basaloid carcinoma | Adenosquamous carcinoma |

Mixed squamous cell carcinomas | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

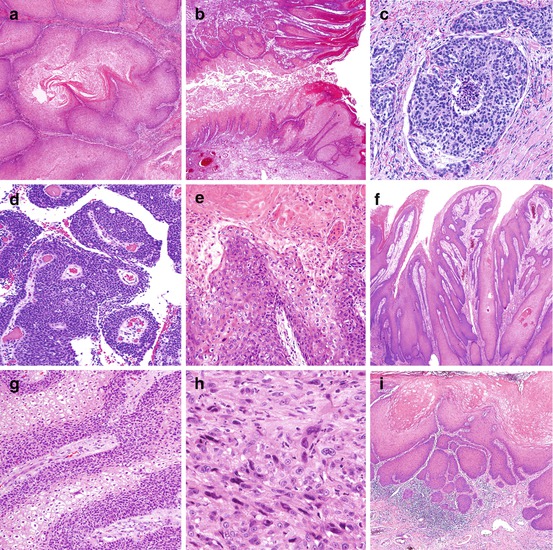

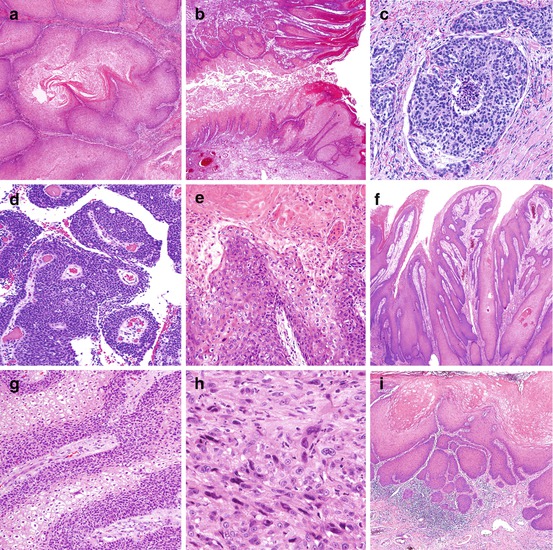

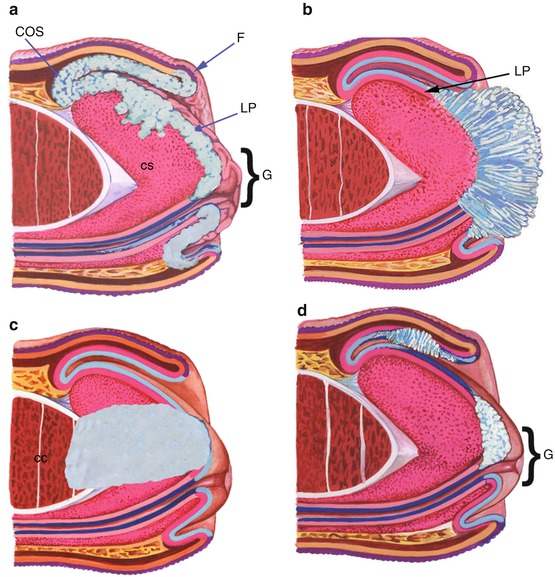

Fig. 3.3

Subtypes of invasive squamous cell carcinomas. (a) Verrucous carcinoma: extremely differentiated, acanthotic, keratinizing carcinoma. There is a sharp delineation between tumor and underlying stroma. (b) Cuniculatum: deeply penetrating low-grade hyperkeratotic tumor. Tumor “burrows” into underlying tissues. Note the verrucous features of the tumor. (c) Basaloid: there is a nesting pattern of growth. Each nest is composed of basophilic small neoplastic cells. There is central necrosis (comedonecrosis). (d) Papillary-basaloid: note the condylomatous papillae with a central fibrovascular core. Cells are basophilic and uniformly small. (e) Warty (condylomatous): there is hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. The papillae are typically condylomatous with a central fibrovascular core and pleomorphic koilocytosis. (f) Papillary, NOS: hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. Papillae are irregular and composed of well-differentiated squamous cells. No koilocytosis is present. (g) Warty-basaloid: tumor invasive nest with both koilocytic (clear) and basaloid (blue) cells. (h) Sarcomatoid: there are spindle and giant cell features simulating a sarcoma. (i) Pseudohyperplastic: extremely well-differentiated SCC with infiltration of preputial lamina propria. The lesion simulates pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia

Carcinoma cuniculatum is a variant of verrucous carcinoma characterized by a distinctive labyrinthine growth pattern simulating rabbits’ burrows (Fig. 3.3b). Similar tumors have been originally described in the plantar region of the foot [13]. Tumor tracts and sinuses are present, often with foreskin fistula formation. No nodal metastases have been reported [14].

Basaloid carcinomas are distinctive and aggressive penile tumors. The gross appearance of the cut surface is characteristic: a solid, tan, firm moderately to deeply invasive neoplasm with yellow foci of necrosis. Microscopically there is a nesting pattern, often confluent, each nest with a solid or necrotic (comedonecrosis) center (Fig. 3.3c). Keratinization, when present, is abrupt and non-gradual. Cells are small or intermediate, basophilic, spindle, or pleomorphic, with many apoptotic and mitotic figures. Vascular and perineural invasion are frequent. Metastasis is present in more than 50 % of the cases [15].

The papillary-basaloid carcinoma, a variant of basaloid carcinomas which may simulate urothelial tumors, has been recently reported. The surface is exophytic and villous. Microscopically the papillae resemble condylomatous papillae, but unlike warty carcinomas composed of keratinized pleomorphic koilocytosis, the cells are uniformly small and basaloid (Fig. 3.3d). Urothelial immunohistochemical markers are negative. Patients with purely exophytic and minimally invasive tumors do well, but if deeply invasive, they carry a potential for nodal metastasis [16].

Warty (condylomatous) carcinomas are verruciform neoplasms with a characteristic cobblestone appearance. The cut surface shows an exoendophytic tumor. Histologically, the tumor at low power resembles condylomas. At high power cells are malignant. The papilla is arborescent with a central fibrovascular core. The cells are keratinized, pleomorphic, and with koilocytosis (Fig. 3.3e). The interface between tumor and stroma is jagged. The differential diagnosis with giant condylomas (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor) may be problematic especially in those atypical. Low-risk HPV by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or a negative p16INK4a immunohistochemical stain would favor a giant condyloma. Prognosis in warty carcinomas is in general good, but occasional nodal metastasis may occur, mainly in deeply invasive carcinomas [17].

Papillary carcinoma, a verruciform tumor, is diagnosed after the exclusion of verrucous and warty carcinomas. Grossly they are exophytic and large. The cut surface shows a jagged interface between tumor and stroma. Microscopically, there is papillomatosis and low-grade histology (Fig. 3.3f). Unlike verrucous carcinomas, acanthosis is not prominent, and the interface of the tumor and stroma is jagged. Unlike warty carcinoma, no koilocytosis is observed. Prognosis is excellent, with infrequent metastases, providing corpora cavernosa is not invaded [18].

Warty-basaloid carcinomas (Fig. 3.3g) are heterogeneous exoendophytic neoplasms. Histologically, mixed features of warty and basaloid carcinomas are noted. Frequently, condylomatous features are present at the surface, and basaloid carcinoma features in the deeper invasive component. In fewer cases, there is a mixture of warty and basaloid features in the invasive tumor (Fig. 3.3g) without papillomatous surface. Metastatic rates are higher than in warty carcinoma but lower than in basaloid carcinoma [19].

Sarcomatoid carcinomas are biphasic epithelial spindle cell neoplasms. Macroscopically, they may be polypoid or hemorrhagic and necrotic. Histologically, they are sarcomatoid spindle and giant cell tumors (Fig. 3.3h) and may simulate malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, or osteosarcoma. Diagnostic clues are tumor location in glans and not in corpora cavernosa (where most sarcomas occur) [2], presence of areas of invasive carcinoma, or foci of penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN). Immunohistochemical stains with high-molecular-weight cytokeratins and p63 are useful for diagnosis. Nodal metastasis and tumor-related death are common [20]. It is the penile carcinoma with the worst prognosis.

Pseudohyperplastic carcinomas are unusual and affect mainly the foreskin of older individuals with long-standing lichen sclerosus. They are extremely differentiated tumors simulating pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (Fig. 3.3i), often multicentric or spread superficially. Secondary tumors may harbor verrucous or papillary features making diagnosis of tumor type difficult. Pseudohyperplastic carcinomas rarely invade beyond lamina propria. In relation with their low grade and superficiality, the prognosis is excellent [21].

Pseudoglandular carcinomas resemble adenocarcinomas. There are acantholytic or adenoid features secondary to central necrosis of tumor nests. There may be a honeycomb polycystic appearance. These tumors are usually of high grade with a high metastatic rate [22].

Mixed squamous cell carcinomas are heterogeneous neoplasms in which more than 2 of the previously described features are present. Common mixtures are verrucous SCC, warty-basaloid, and others.

Surface adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare tumor composed of squamous cell and adenocarcinoma. Glandular differentiation is usually focal and the squamous component predominates. About a dozen cases have been reported [10, 23–25]. The tumor originates in the glans central/perimeatal region and has a tendency for deep infiltration. Most tumors are high grade, with frequent vascular and perineural invasion. The glandular component is positive for mucin stains and CEA.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the penis is an exceedingly rare tumor histologically similar to its cervical counterpart. The neoplasia is composed of cells with squamous and mucinous differentiation and, unlike adenosquamous carcinomas, without well-defined glandular or ductal structures. CEA and mucin stains are positive [26, 27].

Pathological Prognostic Factors: Risk Groups

Pathological Prognostic Factors

Routes of cancer spread: There is a predictable pattern of local, regional, and systemic spread in penile carcinomas. Early invasion is in lamina propria. It follows infiltration of preputial dartos and/or corpus spongiosum. Later and more significant invasion is in skin of the foreskin or corpora cavernosa. Urethral invasion occurs in either early or advanced stages and should not be an indicator of late stage. Intrapenile satellitosis (i.e., nodules of carcinoma separated from the main tumor mass) is a late phenomenon indicative of aggressive behavior [6, 28]. Regional invasion also follows a pattern starting with the sentinel lymph node, usually in the upper inner inguinal quadrant [29], although some tumors metastasize directly to deep inguinal nodes. Skip metastasis to pelvic nodes is most unusual [30]. Penile carcinoma is considered a locoregional disease, but widespread dissemination occurs in 20–40 % of patients. Death from cancer usually occurs within 2–3 years of initial diagnosis [10]. Metastatic sites at autopsy are the lymph nodes (pelvic, retroperitoneal, and mediastinal), liver, lungs, bone, and myocardium [31].

A small biopsy is usually not sufficient for a proper evaluation of all pathological prognostic factors. Histological subtype and tumor grade can be assessed in 70 % of the cases, but tumor depth and vascular invasion are correctly determined in only 9 and 11 % of the cases (as compared with the resected specimen) [32]. Resection specimens such as circumcisions, glansectomies, or penectomies are recommended for the identification of pathologic prognostic factors. The number of tissue sections determines the accuracy of pathologic evaluation and the proper identification of prognostic factors. A detailed protocol for handling circumcisions and penectomies and a check list for prognostic factors are in the manual of the College of American Pathologists [1].

Inguinal nodal metastasis is the single most important adverse prognostic factor. Reported pathological factors related to prognosis are tumor site of origin, tumor growth pattern, histological grade, depth of invasion or thickness in mm, anatomical levels of invasion, histological subtypes, irregular front of invasion, vascular and perineural invasion, positive surgical margins and urethral invasion, HPV, and other molecular factors [3].

Anatomical location: Sites of the primary tumor may have prognostic significance. Tumors exclusive of the foreskin are associated with better prognosis than those exclusive of glans. Tumors in the foreskin tend to be superficial, highly keratinized, associated with lichen sclerosus, and of lower grade, whereas those of the glans tend to be deeper, of higher grade, and associated with HPV. Carcinomas of the foreskin show a lower frequency of regional metastasis [33].

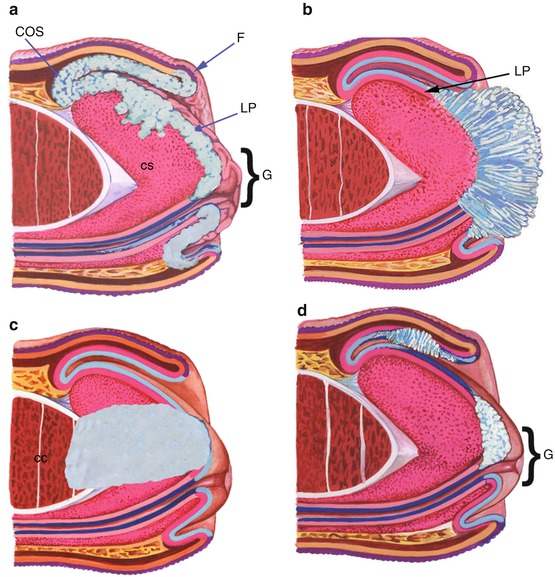

Patterns of growth (Fig. 3.4): Tumors with a superficial spreading growth pattern show a lower incidence of groin metastasis. Tumor recurrence in glans may occur in circumcised patients with superficially spreading tumors due to subclinical microscopic tumors left at the time of original surgery. Verruciform tumors have excellent prognosis despite their occasional large size and deep invasion mainly due to their low-grade histology. Tumors with vertical growth pattern have the worst prognosis with a high metastatic rate. Multicentric tumors are defined as independent noncontinuous foci of carcinoma affecting one or more than one anatomical compartments; they are usually superficial and of low-grade histology [34, 35].

Fig. 3.4

Growth pattern (tumors depicted in light blue). (a) In superficially spreading carcinoma tumor grows horizontally involving lamina propria (LP) and superficial corpus spongiosum (CS) of multiple contiguous anatomical sites. G glans, COS coronal sulcus, F foreskin. (b) In verruciform tumors there is an exophytic and papillomatous growth. Invasion is superficial into lamina propria (LP). (c) Vertical growth: tumor deeply infiltrates into corpus cavernosum (CC). (d) In multicentric tumors, neoplastic growth affects discontinuously more than one anatomical compartment

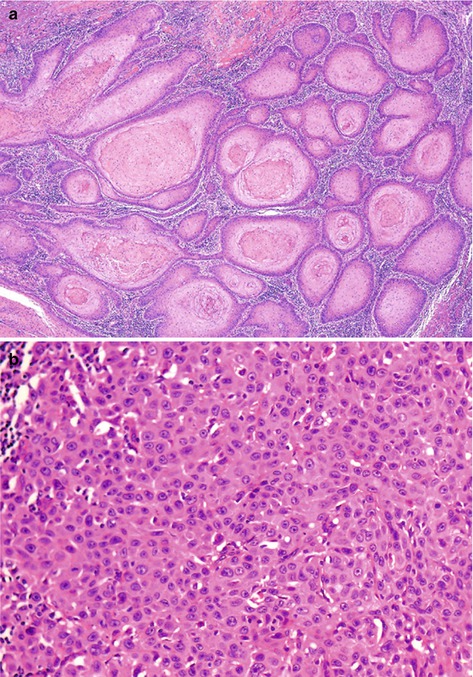

Histological grade: Histologic grade predicts metastasis in penile cancer, but reproducibility of grading systems may be problematic. For this reason it is advisable to select an adequate grading method. Tumor heterogeneity (more than a grade present in the same tumor) should be considered. We use a simple 3-tier system that emphasizes grading both extremes of the differentiation spectrum, well differentiated (grade 1) and poorly differentiated (grade 3) (Fig. 3.5). In the grade two category are the remaining tumors [36, 37].

Fig. 3.5

Histological grade. (a) Extremely well-differentiated (grade I) keratinizing infiltrating SCC. Atypias are minimal. (b) Poorly differentiated (grade III) nonkeratinizing SCC growing in solid sheets

Depth of invasion: Depth of invasion and tumor thickness are significant pathological prognostic factors related to patients’ outcome. Tumors invading less than 5 mm are at low risk for metastasis. Tumors invading more than 10 mm show a high incidence of nodal metastasis (about 80 %). Tumors invading 5–10 mm are problematic to predict. In these instances, perineural invasion (PNI) and histologic grade are helpful features to take into account [37].

Anatomical levels of invasion: The TNM staging system is based on the progressive tumor invasion of anatomical levels [38]. Tumor involvement of anatomical levels correlates with inguinal metastasis. Stage pTis is carcinoma in situ, and pTa corresponds to noninvasive verrucous carcinoma. pT1 invades lamina propria, and pT2 indicates invasion of corpus spongiosum or corpus cavernosum. Tumors invading penile urethra are staged as pT3, and tumors extending to adjacent organs are staged as pT4. Lumping the erectile tissues (corpus spongiosum and corpus cavernosum) into a single pT stage may not be appropriate because of the wide space separating LP from corpus cavernosum (about 10–13 mm) [4]. Tumors superficially invading the corpus spongiosum show a lower metastatic rate, whereas tumors invading deep corpus spongiosum show a higher metastatic rate, similar to those invading corpus cavernosum [7].

Histological subtypes: There is a broad correlation of histologic subtypes of SCC and rates of regional or systemic dissemination in univariate analysis. This is less significant on multivariate analysis [10]. Tumors associated with excellent prognosis are verrucous, papillary, warty, pseudohyperplastic, and cuniculatum carcinomas [2]. The high-risk group for metastasis comprises basaloid, sarcomatoid, adenosquamous, pseudoglandular, and poorly differentiated SCCs [39]. The intermediate category of metastatic risk includes the usual SCC, some mixed neoplasms, and pleomorphic variants of warty carcinomas [10]. In a study of 72 patients, histopathology classification was a significant predictor of lymph node metastasis [40].

Front of tumor invasion: The irregular invasion of small strands of cells was designated as the infiltrative front as opposed to the pushing front (large cell blocks with well-defined tumor borders). Patients with infiltrative tumor front demonstrated in one study to do worse than those with the pushing front [41].

Vascular invasion: Vascular invasion, lymphatic or venous, adversely affects prognosis of penile cancer. In an outcome study of 375 surgical resections, lymphatic invasion was an independent predictor of nodal metastasis [3]. Common sites of lymphatic invasion include the lamina propria underneath the squamous or urethral epithelium and the penile fascia [6]. Venous invasion is less frequent and appears in more advanced cases, mainly related to invasion of corpora spongiosa and cavernosa. Both lymphatic and vascular embolizations were found to be significant predictors of metastasis [42]. The pathological distinction of lymphatic and venular structures may be problematic and immunostains may be useful.

Perineural invasion (PNI) was the most significant single predictor of mortality in a study of 375 resected specimens [10]. In another evaluation of 134 patients with tumors invading from 5 to 10 mm, PNI and histologic grade were the most significant independent predictors of nodal metastasis [37]. For this reason PNI is part of our Prognostic Index (see below).

Resection margins and urethral involvement: Positive resection margins adversely affect prognosis in patients with penile SCCs [6]. Urethral involvement by cancer has been reported as an adverse prognostic factor [38, 43]. Invasion of the anterior urethra occurs in 25 % of cases, and it is not necessarily associated with a poor outcome as a pT3 classification would suggest [44]. Urethral invasion as an adverse prognostic factor should be reevaluated.

Presence of HPV: HPV status has proven to be a significant prognostic factor for survival and therapeutic response in certain head and neck SCCs [45], and a similar trend can reasonably be expected in penile carcinomas. Although HPV has been associated with high-grade tumors [46], the impact on outcomes is unclear. Some reports have not shown any survival difference, but others have reported HPV to be significantly associated with a favorable prognosis [47, 48]. A recent evaluation disclosed a better disease-specific 5-year survival in high-risk HPV-positive comparing with HPV-negative tumors (93 vs. 78 %). In multivariate analysis, the HPV status was identified as an independent predictor for disease-specific mortality [49]. In addition, a study indicated the presence of p16INK4a, a tumor suppressor associated with the presence of high-risk HPV, in penile carcinomas as a survival advantage [50]. Therefore, it has been suggested that high-risk HPV penile tumors comprise a distinct clinical and molecular entity and that survival of patients with HPV-positive carcinomas may be related to a lower degree of gross genetic alterations.

Other molecular prognostic factors: A number of immunohistochemical markers of interest in the potential prediction of biologic behavior have been investigated in penile cancer, including the cell cycle-associated proteins Ki-67, p53, and p16INK4a [51, 52]. Ki-67 is a marker of cell proliferation that has been used to predict malignant behavior. p53 is a tumor suppressor protein that is often mutated in cancers, leading to its accumulation in malignant cells. However, the HPV E6 protein inactivates p53; therefore, its expression in HPV-related tumors is thought to be downregulated, at least in squamous cell carcinomas of the gynecologic tract [52]. However, overexpression of p53 on immunohistochemistry has been found in both HPV-positive and HPV-negative patients [50, 52, 53]. This supports the notion that these pathways of carcinogenesis are not mutually exclusive. Finally, p16INK4a is a tumor suppressor protein known to accumulate in HPV-related tumors in response to Rb inactivation by the viral E7 protein [54]. Overexpression of p16INK4a can be used as a reliable marker for the presence of high-risk HPV DNA and as a tool in the differential diagnostic of penile subtypes. p16INK4a-positive tumors more likely exhibit a basaloid and/or warty morphology, whereas the negative cases tend to correspond to well-differentiated, keratinizing, low-grade variants of penile SCC [55]. Other suggested markers are E-cadherin, MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinase-9), annexins I and IV, and decreased KAI1/CD82, a metastasis suppressor gene [56–60]. A focus of current research is to identify additional prognostic biomarkers in penile cancer.

Pathological Risk Groups for Prediction of Inguinal Metastasis and Outcome

The dynamic sentinel node biopsy is considered the best clinical instrument for detection of early nodal metastasis [61]. Before a wider dissemination of this method, not available in underdeveloped countries where penile cancer abounds, other methods more dependent of pathological findings were devised. A combination of prognostic significant factors forms the stratification risk groups. The better-known systems by Solsona et al. [62] and Hungerhuber et al. [63] are based on the combination of histologic grade and depth of invasion. A third system, which we use in our clinical practice for all invasive penile cancers, combines anatomical level of invasion, tumor grade, and perineural invasion [7]. There are three risk categories in all systems: low, intermediate, and high.

Solsona et al. [62] series comprises 33 patients with penile cancer. Patients with pT1 stage and grade 1 tumors are in the low-risk category. The high-risk category is for patients with stages pT2/pT3 and grades 2 or 3 tumors, whereas the intermediate group encompassed the remaining patients. Inguinal metastases appeared in 0, 33, and 83 % of the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories. Surveillance is proposed for the low -risk and lymphadenectomy for the high-risk group. They recognized the difficulty for an optimal approach for patients in the intermediate group.

Hungerhuber et al. [63] series was of 56 patients with inguinal lymphadenectomy. Patients with grades 1 or 2 and stage pT1 tumors were in the low-risk category. Patients with grade 3 tumors were in the high-risk group and the remaining in the intermediate category. Inguinal metastases were found in 8, 29, and 75 % of the patients in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. They recommended prophylactic lymphadenectomy for patients in the high-risk group and surveillance for those in the low-risk category. For the problematic intermediate group, authors suggested the dynamic sentinel lymph node biopsy [30].

The third system, named “Prognostic Index,” was validated in a series of 193 patients with penile cancer [7]. Risk groups were based on scores obtained by the addition of numerical values given to histologic grade, deepest anatomical level involved by cancer, and presence of PNI. For histologic grades, the numerical values were 1, 2, and 3 points for well-, moderately, and poorly differentiated carcinomas. Values for anatomical levels were 1 point for lamina propria, 2 points for corpus spongiosum or dartos, and 3 points for corpus cavernosum or preputial skin. PNI was evaluated as follows: absence of PNI, 0 points, and presence of PNI, 1 point. Scores ranged from 2 to 7 points. Using this system, the inguinal metastatic rate was 0 % for the low-risk group (scores 2 and 3), 20 % for the intermediate-risk group (score 4), and 64 % for the high-risk group (scores 5–7). In addition, scores obtained with this system were also useful to predict survival. Patients with scores 2–4 had a 5-year survival rate of 95 %. The survival rate of patients with scores 5 and 6 was 65 %, whereas the score 7 was associated with a survival rate of 45 %. This method requires a resected specimen and a thorough pathological evaluation. It needs to be tested in patients with nonpalpable inguinal lymph nodes.

Nomograms to predict patient outcome have been recently designed. The first includes eight clinical and pathologic variables [64] selected from a multivariate analysis performed on 175 patients from 11 institutions. The following data were used: clinical stage of lymph nodes, microscopic growth pattern, histologic grade, vascular invasion, and invasion of corpus spongiosum, corpus cavernosum, and urethra. The model showed good prognostic accuracy and calibration. The probability of nodal metastasis, as predicted by the nomogram, was close to the actual incidence of metastasis observed at follow-up. A second nomogram was devised using the same clinical and pathologic factors with similar outcomes [65]. The third nomogram was based on a multivariate and regression analysis of pathologic data from 134 uniformly surgically treated patients with penile cancer most of them in the intermediate-risk category. PNI and histological grade were the strongest predictors of mortality in tumors measuring 5–10 mm in thickness. A nomogram was accordingly constructed using PNI and histological grade [37]. The probability of metastasis in grade 1 tumors without PNI was near zero; in tumors with grade 1 and PNI, the probability was 18 %. Grade 2 tumors without PNI had a probability of metastasis of about 40 %, but when PNI was present, it rose to 70 %. For grade 3 tumors without PNI, the probability of metastasis was 55 %; with PNI, the probability of metastasis was 80 %.

HPV in Penile Carcinomas

General Features

Penile cancers are likely to be initiated by interference with the cellular p14ARF/MDM2/p53 and/or p16INK4a/cyclin D/Rb pathways, either by viral or nonviral mechanisms. This may lead to uncontrolled cell division and reduced apoptosis and may trigger a state of chromosomal instability that further drives the carcinogenic process. More common molecular events in late-stage penile carcinogenesis include altered expression of genes involved in disease progression, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. HPV was found to be an important factor in penile cancer pathogenesis [46]. Epidemiological research has classified 15 genotypes of HPV as high risk, based on their association with cervical cancer, HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-35, HPV-39, HPV-45, HPV-51, HPV-52, HPV-56, HPV-58, HPV-59, HPV-68, HPV-73, and HPV-82, and three types as probably high risk, HPV-26, HPV-53, and HPV-66 [66].

Kurman seminal study established the association of HPV with morphology indicating the correlation of the virus with histological subtypes of vulvar squamous cell carcinomas [67]. Gregoire also found, using cases from New York and Paraguay, a preferential detection of HPV in penile carcinomas of basaloid and mixtures of warty and basaloid morphology. Other tumors, such as verrucous, papillary NOS, and usual squamous cell carcinomas, are less frequently associated with the virus [46]. Despite the geographical coexistence of high incidence rates of cervical and penile cancer, it was noted that penile tumors pathologically resemble vulvar rather than cervical carcinomas. Penile HPV-positive carcinomas are, however, identical to cervical cancers. Near 100 % of cervical SCCs are HPV related [68], whereas it is found in about one third to one half of penile and vulvar cancers [69, 70]. For these reasons, a dual pathogenesis has been postulated for these tumors [46, 71]. Prevalence rates vary widely in the literature from 20 to 80 % with an average detection rate of 48 % [72, 73]. Variations in HPV detection rate may be related to (1) geographical prevalence differences of environmental factors (sexual habits, socioeconomic status, and/or cultural practices), (2) technical problems resulting in failures in the detection of HPV DNA by using inappropriate methods or testing the sample only once, (3) poor DNA preservation or degradation of tissue samples (DNA detection using PCR is highly sensitive, and tissue fixation for more than 24 h and the use of non-buffered formalin reduce the chances of detection), and (4) lack of experience or use of variable morphologic criteria for tumor classification resulting in low concordance rates when comparing series. Patients with HPV-positive tumors are about 10 years younger than those with HPV-negative tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree