Fig. 2.1

Classification of the depth of invasion

2.2 Macroscopic Features

2.2.1 Handling of Specimens

The proper handling of a specimen by a competent pathologist is the most important step to render an accurate diagnosis and to generate a comprehensive pathology report that will characterize patient management and prognosis. The resected esophagus should be opened along the longitudinal line on the opposite side of the deepest cancer invasion. The specimens should be stretched out to approximate the length to what is in the patient’s body and should be pinned out on flat boards with the mucosal side up before fixation. After applying iodine solution on the esophageal mucosa, superficial esophageal cancers should be sectioned in its entirety [1–3]. The endoscopically resected specimen should be sectioned serially at 2–3 mm intervals parallel to a line that includes the closest part between the margin of the specimen and of the neoplasm, so that both lateral and vertical margins are assessed [1–3] (Fig. 2.2a, b). Spraying the mucosa with iodine solution is the standard method for gross examination of the specimens with abnormal squamous lesions. Iodine staining method significantly improves delineation of abnormal squamous lesions (Fig. 2.3a, b). Glycogen in the normal squamous epithelium interacts with iodine and shows a brown color, whereas in abnormal squamous mucosa, including areas of squamous dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma, atrophy, keratinization, parakeratosis, and esophagitis, the squamous epithelium often loses glycogen and remains partially or totally unstained [7–12]. Glandular mucosa, including normal gastric mucosa, gastric heterotopia, and Barrett’s mucosa, also appears unstained [13]. Foci of glycogenic acanthosis appear overstained [10].

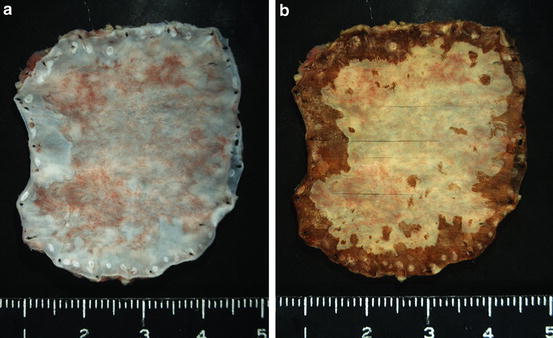

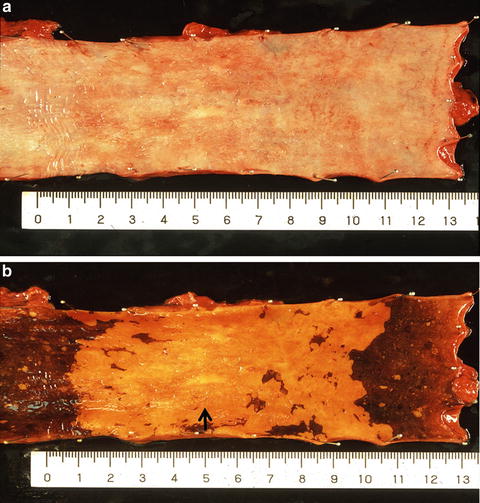

Fig. 2.2

(a) A 0-IIc type superficial esophageal carcinoma resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). (Courtesy of Dr. Tateishi (Department of Pathology, Yokohama City University, Yokohama) and Dr. Hishima (Department of Pathology, Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital, Tokyo). (b) After fixation and iodine staining, the specimen was sectioned serially at 2–3 mm intervals

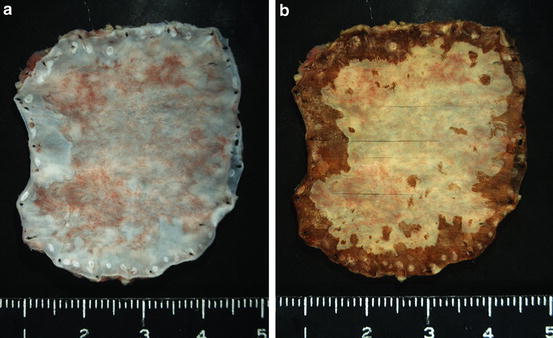

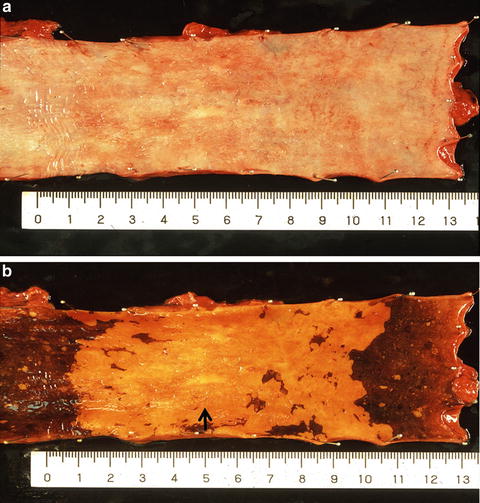

Fig. 2.3

(a) A shallow depressed lesion (0-IIc type) resected by esophagectomy. (b) Iodine staining clearly revealed an unstained area. This 0-IIc type cancer showed submucosal invasion in the whitish discolored area (arrow). This cancer can be also classified as a superficial spreading type which is defined as a superficial esophageal cancer with more than 5 cm superficial spreading

2.2.2 General Features

Squamous cell carcinoma can occur in any portion of the esophagus but is most common in the middle third [14]. Superficial esophageal cancers appear as pink-tan or gray-white, shallow depressions, plaque-like thickenings, or elevations of mucosa. Advanced esophageal cancers grow into exophytic or ulcerated masses and obstruct the lumen.

2.2.3 Superficial Esophageal Cancer

Superficial esophageal cancers are classified as subtypes of type 0 and further subclassified into three major types including type 0-I, type 0-II, and type 0-III, based on the presence of elevation and depression [1–3] (Fig. 2.4). Type 0-I is a superficial and protruding type and includes type 0-Ip, which is pedunculated, and type 0-Is, which is sessile. Type 0-II is a superficial and flat type and is further subclassified into three subtypes, namely type 0-IIa, which is slightly elevated up to 1 mm in height, type 0-IIb, which is completely flat, and type 0-IIc, which is slightly depressed (Fig. 2.3a, b). Type 0-III is a superficial and excavated type.

Fig. 2.4

Macroscopic classification of superficial esophageal carcinoma

The 0-Ip cancer is most typically seen in esophageal carcinosarcoma (sarcomatoid carcinoma) (Fig. 2.5) [15]. The 0-IIc cancer is most common in superficial esophageal cancers [16, 17]. Type 0-IIb cancer is almost always mucosal cancer, whereas type 0-IIc cancer consists of squamous cell carcinoma showing a wide range of cancer invasion depth from mucosal to submucosal invasion [17, 18]. More protruded (type 0-I) or more depressed (type 0-III) lesions are associated with deeper invasion in the submucosa [17, 18]. This applies particularly when the lesion has a mixed morphologic pattern. Many superficial esophageal cancers show combined types, e.g., a shallow depression and a sessile protrusion, 0-IIc + “0-Is” (Fig. 2.6). In the combined types, the type occupying the larger area should be described first, followed by the next type according to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer [1–3]. Double quotation marks (“”) are placed around the macroscopic tumor type that has the deepest tumor invasion.

Fig. 2.5

A typical 0-Ip type superficial esophageal carcinoma (carcinosarcoma), which appears as a large polypoid tumor with a smooth surface and prominent lobulation. The stalk is very small and narrow, and not visible in this picture. Erosive superficial squamous cell carcinoma surrounding the polypoid tumor is also noted

Fig. 2.6

A 0-IIc + “Is” type superficial esophageal cancer. The sessile portion (0-Is type) showed a deepest cancer invasion

2.2.4 Advanced Esophageal Cancer

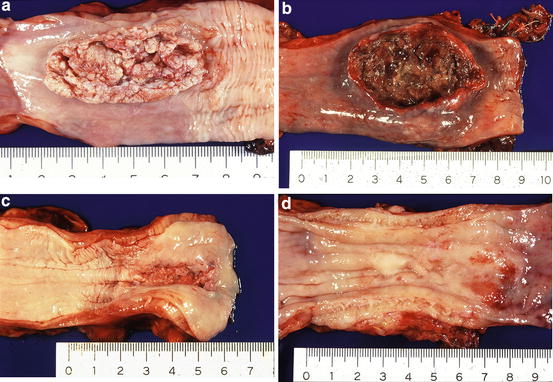

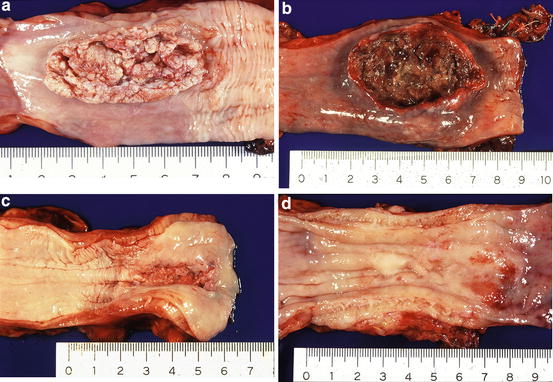

Advanced esophageal cancers are classified into four types [1–3]. A type 1 tumor is defined as a protruding tumor (Fig. 2.7a). A type 2 tumor is defined as an ulcerated tumor with a sharply demarcated raised border (Fig. 2.7b). A type 3 tumor is also an ulcerated tumor, but shows infiltration into the surrounding wall, making the tumor border rather unclear (Fig. 2.7c). A type 4 tumor is defined as a diffusely infiltrating tumor in which ulceration or protrusion is usually not a prominent feature (Fig. 2.7d). A type 5 tumor is defined as a tumor that cannot be classified into any of these types. Superficial esophageal cancer can be found at the periphery of an advanced tumor. When an advanced tumor shows a combined type, the most advanced type is described first and double quotation marks are unnecessary according to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer [1–3]. The macroscopic classification of ESCC can be applied to all esophageal adenocarcinomas.

Fig. 2.7

(a) A type 1 tumor (protruding tumor). (b) A type 2 tumor (an ulcerated tumor with a sharply demarcated raised border). (c) A type 3 tumor (an ulcerated tumor with an unclear border). (d) A type 4 tumor (a diffusely infiltrating tumor)

The two most frequent types of advanced cancer are types 2 and 3 [16]. Protruding type tumors are usually found to be carcinosarcomas (sarcomatoid carcinoma), squamous cell carcinomas, or malignant melanomas [19]. Protruding type tumors, especially showing a subepithelial growth, are small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, basaloid squamous carcinomas, and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas (esophageal carcinomas with lymphoid stroma) [19].

2.2.5 Multicentric Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Field Cancerization)

The presence of other cancers synchronously or metachronously associated with esophageal carcinoma is relatively common. According to the comprehensive registry of esophageal cancer in Japan, up to 47 % of patients with esophageal carcinoma had synchronous or metachronous carcinoma at another sites including the stomach, head and neck, colon/rectum, and lung in this descending order [16]. Up to 20 % of patients with ESCC had synchronous or metachronous multiple primary cancers of the esophagus [16]. ESCC, especially multicentric squamous cell carcinoma, is often associated with multiple small areas unstained with Lugol’s iodine observed in the mucosa surrounding esophageal carcinomas (Fig. 2.8) [8]. Patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, who have a high risk for ESCC, are also reported to be frequently associated with multiple iodine-unstained areas [8, 20, 21]. The incidence of multiple small areas unstained with iodine has been reported to be associated with the development of multiple primary cancers in the upper aerodigestive tract and the patients’ tobacco and alcohol consumption [8]. Also, male sex and presence of the aldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (ALDH2) allele has been reported to be associated with an increased risk for multiple Lugol-voiding lesions of the esophageal mucosa in patients with ESCC [22]. Therefore, iodine staining method is useful not only for optimal visualization of esophageal squamous mucosal abnormalities but also for detecting groups at high risk of multicentric cancer in the upper aerodigestive tract. Although staining the esophageal mucosa with iodine solution has not often been used by endoscopists and pathologists in North America, iodine staining is the sine qua non diagnostic method for ESCC.

Fig. 2.8

Iodine staining clearly reveals two unstained cancerous areas. In addition to the cancerous areas, there are multiple small iodine-unstained areas in the mucosa surrounding the cancerous lesions

2.2.6 Risk Factors

Risk factors include alcohol [23], tobacco use [23], history of upper aerodigestive tract cancer [23], achalasia (Fig. 2.9) [23], severe caustic injury [23], frequent consumption of very hot beverages [24], prior radiation therapy to the mediastinum [25], nonepidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma (tylosis) [23], Plummer-Vinson syndrome [26], nutrition (e.g., nitrosamines in pickled or moldy foods) [27], celiac sprue [28], and lichen planus [29].

Fig. 2.9

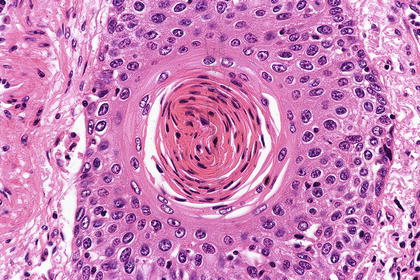

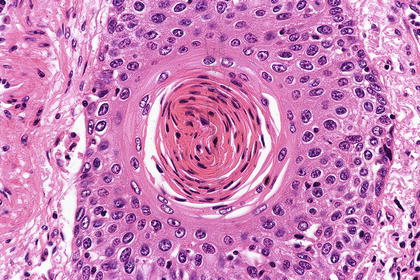

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by stratified squamous differentiation and prominent keratinization

2.3 Microscopic Features

The histology of ESCC is similar to that of squamous cell carcinoma of other sites with enlarged, often vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic opaque cytoplasm. Variable amounts of keratinization with intercellular bridges and/or stratified squamous differentiation are observed depending on tumor differentiation grade. The neoplastic cells form variably sized irregular tumor nests with variable amount of desmoplastic reaction and inflammatory response. Zonal squamous differentiation with keratinization and vague palisading of basaloid tumor cells in the periphery of tumor nests recapitulate the organization of normal stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 2.10). According to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer [1–3], well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is characterized by extensive keratinization and stratified squamous differentiation, accounting for more than three quarters of the tumor area (Fig. 2.10), whereas poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma has such keratinization accounting for less than one quarter of the tumor area. Moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma lies between these two. The WHO classification states that grading is traditionally based on mitotic activity, nuclear atypia, and degree of squamous differentiation, with no special reference to the ratio of keratinization [4]. No widely accepted, well-tested grading system is not established. Most of ESCCs show a characteristic histomorphology, so that the diagnosis might be unproblematic. The differential diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, especially poorly differentiated type, in a biopsy or surgical specimen includes reactive squamous epithelium, undifferentiated carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, salivary gland-type carcinoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (e.g., pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia associated with granular cell tumor [30]), radiation effect, hyperplastic polyp of the esophagogastric junction [31], malignant melanoma, and metastatic tumor. The main differential diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in a biopsy specimen is usually a reactive squamous epithelium. Immunohistochemistry (e.g., p63 and cytokeratin 5/6) can provide assistance in the differential diagnosis, as well as review of imaging studies.

Fig. 2.10

A type 2 advanced esophageal cancer developed in Achalasia

2.4 Tumor Spread

ESCC shows unique patterns of tumor spread including ductal/glandular involvement, diffuse pagetoid spread, and intramural metastasis like those frequently seen in other organs such as the uterine cervix and nipple.

2.4.1 Superficial Esophageal Cancer

ESCC begins as an in situ carcinoma and spreads both horizontally and vertically. Initial invasion into the lamina propria is characterized by the proliferation of downward growth of neoplastic squamous epithelium. It is a distinctive feature of ESCC that lymph node metastases occur early in the course of the disease. The abundant lymphatic channels in the lamina propria mucosae and submucosa of the esophagus are responsible for the high frequency of lymph node metastasis [32, 33]. All submucosal tumors have a substantial risk of lymph node metastases [17, 18].

2.4.1.1 Ductal/Glandular Involvement

The esophageal submucosal glands are considered to be a continuation of the minor salivary glands and scattered throughout the entire esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ can extend into the ducts of the submucosal glands. Ductal/glandular involvement has often been observed in superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, with an incidence of 21.3–22.3 % [34, 35]. Maximum tumor size has been reported to correlate with the presence of ductal/glandular involvement by multivariate analysis, indicating that ductal/glandular involvement develops in association with horizontal tumor growth [34]. According to the Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, tumors with ductal/glandular involvement that extends to the submucosa but does not definitely invade the submucosal stroma should not be classified as submucosal carcinoma [1–3]. However, even in mucosal carcinoma, there exists a possibility of incomplete clearance of the tumor tissue by endoscopic resection due to the presence of ductal/glandular involvement extending to the submucosal layer or reaching the end portions of esophageal glands. Also, it is very important to judge accurately whether a small cancerous nest in the submucosal layer in an endoscopically resected specimen is ductal/glandular involvement, direct tumor invasion, or lympho-vascular invasion in deciding the necessity for additional surgical resection based on the histopathologic findings in endoscopically resected specimens. Immunohistochemistry (e.g., CD31, D2-40) and elastic stain can be helpful in the differential diagnosis as well as deeper cut sections.

2.4.1.2 Diffuse Pagetoid Spread

Occasionally, squamous cell carcinoma cells exhibit a pagetoid pattern of growth. However, diffuse pagetoid spreading of squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the esophagus is very rare and is characterized by the pronounced pagetoid spread of squamous cell carcinoma [36, 37]. Pagetoid spread of squamous cell carcinoma in situ and true Paget’s disease are very similar histologically.

2.4.2 Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients with Superficial Esophageal Cancer

The proportion of patients with superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus and lymph node metastasis has been reported to be 39–54 %, whereas the proportion of patients with intraepithelial carcinoma (EP (M1)) or carcinoma invading the lamina propria (LPM (M2)) and lymph node metastasis is only 1.4–4.0 % [17, 18, 38, 39]. The risk of lymph node metastases is surprisingly high when it reaches the muscularis mucosae (MM (M3). 5.0–18.0 %) or the superficial submucosa (SM1, 26.5–53.9 %) [17, 18, 38, 39]. Consequently, intraepithelial carcinoma (EP (M1)) or carcinoma invading the lamina propria (LPM (M2)) is generally treated by endoscopic resection [1–3]. Tumors with an estimated depth of invasion of MM (M3) or SM1 without lymph node metastases on diagnostic imaging studies are considered to have a relative indication for endoscopic resection, whereas tumors with an estimated depth of invasion of SM2 or SM3 have no indication for endoscopic resection [1–3]. However, clinical diagnosis of the depth of invasion is not always accurate. One of the major advantages of endoscopic resection is to recover a specimen for histopathologic analysis, which helps to make a clinical decision for further therapy after endoscopic resection. Previous studies have reported that lymphatic invasion was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis in patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma in a multivariate analysis [38, 39].

2.4.3 Advanced Esophageal Cancer

Advanced esophageal cancers may invade surrounding structures including the trachea, lung, aorta, mediastinum, and pericardium. Distally located tumors often invade the stomach. Metastases to distant organs are frequent, particularly to the liver and lung [14, 16].

2.4.3.1 Intramural Metastasis

Metastasis from an esophageal carcinoma to the esophagus or stomach is termed intramural metastasis. Intramural metastasis has often been found in the resected esophagus, with an incidence of 11–15 % [40, 41]. Patients with intramural metastasis have a higher frequency of lymph node metastasis and liver recurrence than those without intramural metastasis, and intramural metastasis is more predictive of a worse prognosis than is local recurrence [40].

2.4.3.2 Prognostic Factors

Clinicopathologic prognostic factors include TNM stage [1–3], lymph node metastasis [42, 43], tumor invasion depth [42, 43], lympho-vascular invasion [43], intramural metastasis [40, 43], tumor vascularity [44], infiltrating growth pattern [45], inflammatory response [45, 46], tumor budding [47], tumor nest configuration [48], extranodal spreading [49], epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype [50], pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy [51], completeness of surgical resection [42], and the patient’s general health condition [52]. Most of these studies have shown no significant influence of tumor differentiation grade on survival. Among these clinicopathologic prognostic factors, the number of metastasis-positive lymph nodes is a simple and reliable prognostic factor [53, 54]. In patients with tumor limited to within the submucosal layer, even with tumors located in the mid- and lower esophagus, lymph node metastasis was frequent in the upper mediastinum and perigastric area [55]. Isolated distant lymph node involvement from superficial esophageal carcinoma is thus not necessarily a sign of advanced disease [55]. The most predictive factor for patient’s survival is not the area of involved nodes, but the number of involved nodes [56, 57]. Numerous genes, proteins, and microRNAs are involved in the development of ESCC [58–60]. Most of them are involved in signal transduction, regulation of transcription, cell cycle, or cell apoptosis [58]. Such markers may have potential implications in early detection of tumorigenesis and prediction of metastasis and survival. Among those, cyclin D1, p53, E-cadherin, and VEGF have been reported to be most potential markers in ESCC according to the review of protein alterations in ESCC and clinical implications [58].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree