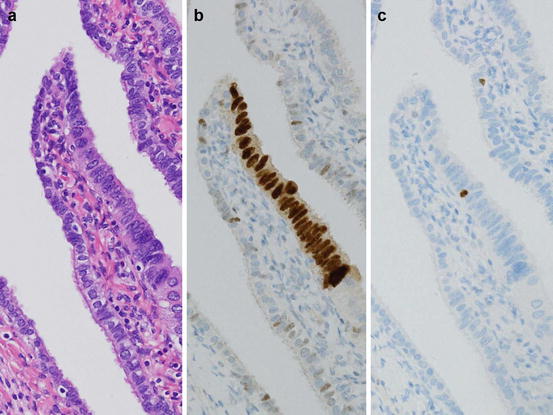

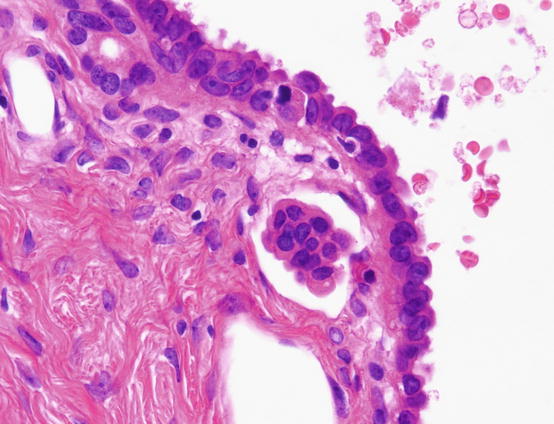

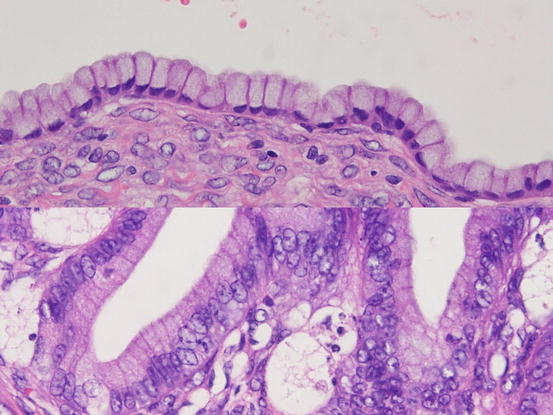

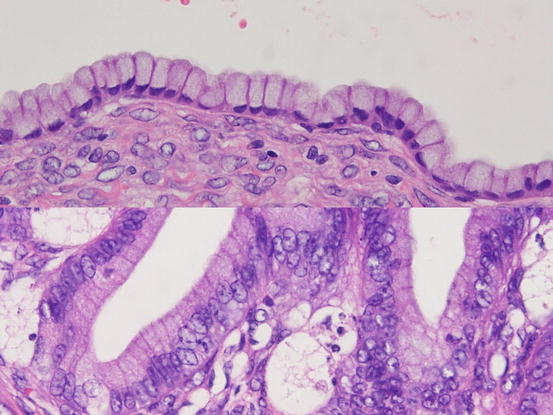

Fig. 5.1

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Proliferation of epithelial cells with high-grade atypia replaces the surface of tubal fimbrial epithelium. (a) low power, (b) high power

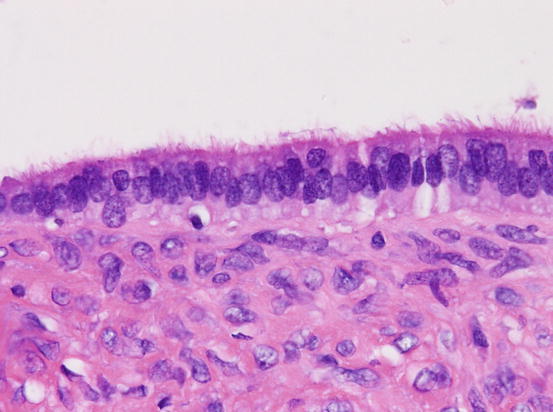

Fig. 5.2

p53 signature. The fimbrial epithelium without nuclear atypia (a) has focus of continuous p53 positivity (b). Ki-67 positive cells are not increased (c)

Ovarian inclusion cysts have previously been considered to be precursors of serous cystadenoma or serous borderline tumors. Recently, however, it has been suggested that some inclusion cysts are derived from implanted tubal epithelium, not from ovarian surface cells [7]. Since aneuploidy of inclusion cyst epithelium is frequently associated with serous borderline tumors, inclusion cysts could be precursor of serous borderline tumors [8]. Moreover, some investigators propose that high-grade serous carcinoma could also originate from inclusion cysts. Together, these observations and hypotheses suggest that at least some serous tumors are ultimately derived from tubal epithelium.

Abovementioned “tubal origin” theory of ovarian tumorigenesis cannot explain origin of all serous tumors because some of them lack tubal precursor lesions instead of exhaustive search. Some researchers have claimed that some ovarian epithelial tumors derived from OSE or inclusion cysts derived from invaginated OSE [9]. Since both OSE and Müllerian epithelium develop from coelomic epithelium, it is thought that OSE has the ability to differentiate Müllerian epithelium and transform to epithelial tumors. Some morphological and immunohistochemical observations support this metaplasia and transformation theory. In addition, animal models with genetic alterations showed induction of carcinoma from OSE.

Another possible origin of ovarian epithelial tumors is epithelium of endometriosis. Strong association between endometrioid, clear, and seromucinous tumors and endometriosis has been described, resulting in these tumors being designated as endometriosis-related ovarian neoplasms (ERONs) [10]. Endometriosis with cellular atypia (atypical endometriosis) is thought to be a precursor of ERONs. ARID1A mutation is frequently detected among ERONs in whole genome analysis; for example, 50% of clear cell carcinomas (CCCs) and 40% of endometrioid carcinoma have this mutation [11, 12]. One immunohistochemical study showed that 33% of seromucinous borderline tumor might harbor an ARID1A mutation [13]. ARID1A encodes the protein BAF250a, a subunit of switch/sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex, which binds to AT-rich DNA sequences, and participates in chromatin remodeling and regulation of gene transcription. Mutation of ARID1A results in defective BAF250a and loss of function as tumor suppressor molecule. Since mutation of ARID1A is observed in epithelium of atypical or normal-appearing endometriosis adjacent to ERONs, it might be an early event of ERON tumorigenesis [12].

Although the histogenesis of mucinous tumors is uncertain, their association with teratomas and Brenner tumors sheds light on their origin. Fujii et al. conducted molecular study of mucinous tumors associated with teratomas and showed that these tumors are derived from germ cells [14]. Frequent coexistence of mucinous and Brenner tumors suggests a possible common origin. Some studies showed that Brenner tumors and associated mucinous tumor harbored identical gene mutations and suggested that some mucinous tumors developed from Brenner tumors [15–17] (see also Sects. 3.1.2 and 3.4.4 in Chap. 3).

5.4 Serous Tumors

Serous tumors are composed of an epithelium resembling the fallopian tube epithelium and often have psammoma bodies. Serous tumors are the most common ovarian epithelial tumors; in the Western world, approximately 60% are benign, 10% borderline, and 30% carcinoma [18]. Nakashima et al. reported the same distribution for patients in a Japanese institute [19].

5.4.1 Benign Serous Tumors

Serous adenomas occur in women of a wide age range. Most serous adenomas are uni- or oligolocular cystic tumors (serous cystadenoma). Sometimes, they show surface papillary growth (serous surface papilloma) or have a prominent solid fibrous component (serous adenofibroma). Usually, tumors are less than 10 cm in size. Inner surface of cysts is usually flat or shows low elevated nodules. Differentiation between ovarian inclusion cysts and serous cystadenomas is arbitrary, and cystic lesions with tubal-type epithelium larger than 1 cm are diagnosed as serous cystadenomas [1].

Microscopically, a single layer of cuboidal to low columnar epithelium lines the inner surface. Some tumor cells have cilia on their surface (Fig. 5.3). Papillary proliferation of less than 10% of the tumor area is compatible with benign serous tumors. The stromal component of adenofibroma is composed of spindle cells without remarkable cellular atypia.

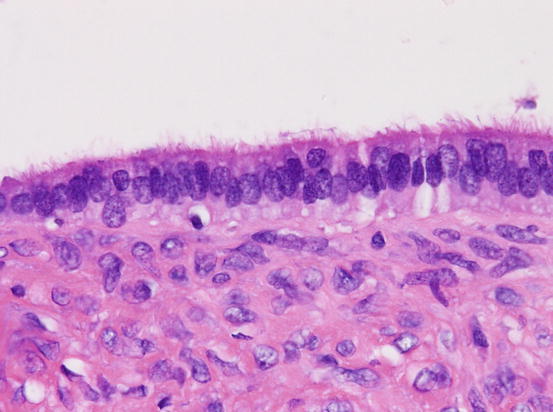

Fig. 5.3

Serous adenoma. The inner surface of cystic tumor is lined by single layer of ciliated epithelium

Benign serous tumors present with characters of tubal epithelium. Like tubal epithelium, tumor cells are cytokeratin (CK) 7 positive and CK20 negative; they are also estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive in most cases. Like tubal epithelium, serous tumors express WT1.

Most serous adenomas are polyclonal and lack mutation of KRAS or BRAF genes. Large serous adenomas tend to be monoclonal [20].

5.4.2 Serous Borderline Tumor/Atypical Proliferative Serous Tumor

A serous borderline tumor/atypical proliferative tumor (SBT/APT) is characterized by proliferative activity between clearly benign and clearly malignant tumors and the absence of frank stromal invasion. The mean age of patients is 42 years [21]. SBT/APTs are histologically classified as either usual or micropapillary type. Since micropapillary SBTs are more frequently associated with extraovarian invasive implants and poorer outcome than usual SBT/APTs [22], some investigators have proposed that these tumors should be diagnosed as noninvasive serous carcinomas. On the other hand, others claim that a micropapillary pattern is not in itself an independent prognostic factor [21]. In the WHO classification 2014, the term noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC) is used as a synonym of micropapillary SBT.

5.4.2.1 Usual Serous Borderline Tumor/Atypical Proliferative Serous Tumor

Usual SBTs/APTs have papillary excrescence as intracystic or surface papillary pattern, or both. They have hierarchical papillary proliferation of cuboidal to low columnar cells with some ciliated cells resembling the fallopian tube epithelium and large cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 5.4). Atypia is mild to moderate and mitotic figures are rare.

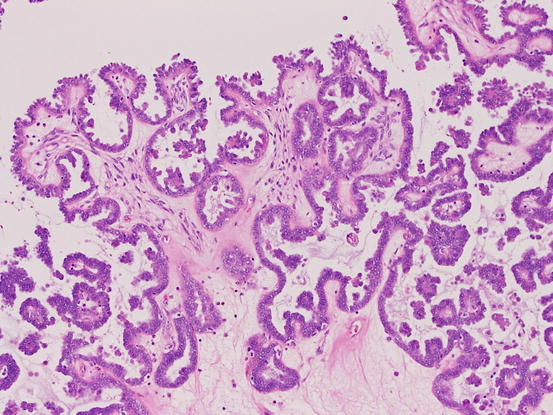

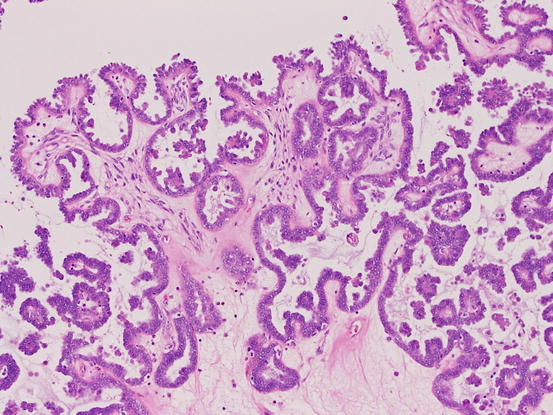

Fig. 5.4

Serous borderline tumor, usual type. The tumor shows hierarchical papillary growth

Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are positive for ER, PR, WT1, and PAX8. Unlike high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSCs), SBT/APTs do not harbor a TP53 mutation, and p53 immunoreactivity of these tumors is weak and patchy (wild-type pattern). SBTs/APTs also show patchy or focal expression of p16 [23].

5.4.2.2 Micropapillary Variant Serous Borderline Tumor (Noninvasive Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma)

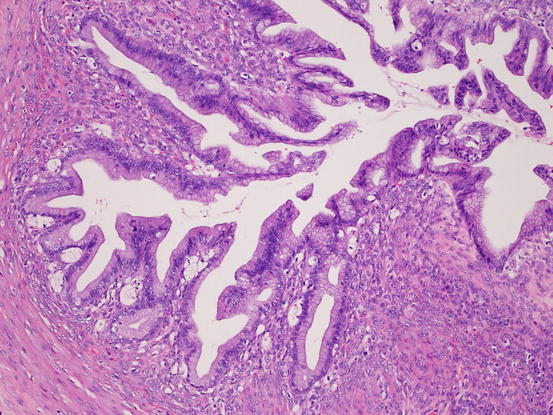

Micropapillary proliferation in SBTs is defined as long (fivefold longer than the width) non-hierarchical papillary growth directly arising from the thick stalks or inner surface of the cyst (Fig. 5.5). This pattern of growth is known as the filigree or medusa head pattern. Cribriform growth in a similar pattern also constitutes part of the micropapillary pattern. A micropapillary component larger than 5 mm in one dimension warrants a diagnosis of micropapillary SBT. Micropapillary SBTs are composed of uniform small and cuboidal to low columnar cells, and ciliated cells are rare. Their immunohistochemical findings are almost identical to usual SBTs/APTs.

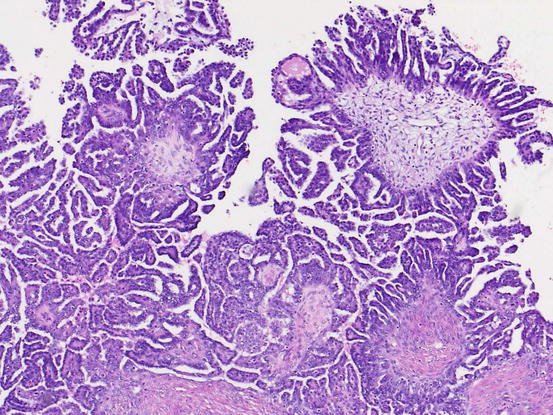

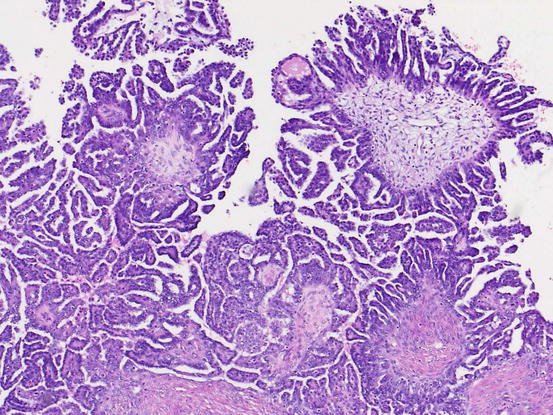

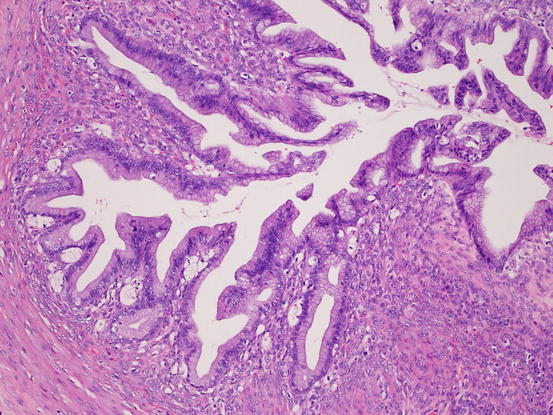

Fig. 5.5

Micropapillary variant of serous borderline tumor/noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma. The tumor shows non-hierarchical, filigree pattern

5.4.2.3 Serous Borderline Tumor with Microinvasive Components

About 10% of all SBTs/APTs have foci of minute stromal invasion. Microinvasion, that is, invasive lesions less than 5 mm in size, is acceptable with a diagnosis of SBT/APT. Microinvasive lesions are further subclassified into two categories according to histological findings [24]. The first is classical microinvasion, which is characterized by individual or a small cluster of eosinophilic cells in the stroma that are terminally differentiated or in senescence (Fig. 5.6) [25]. This pattern of microinvasion is not associated with an aggressive course, whereas the second pattern, which is characterized by complex, branching micropapillae embedded in the stroma and surrounded by a cleft, has an unfavorable prognosis. Histological similarity and unfavorable prognosis has led some pathologists to propose that the second pattern of microinvasion is a small LGSC component and should be diagnosed as an SBT/APT with microinvasive carcinoma [26].

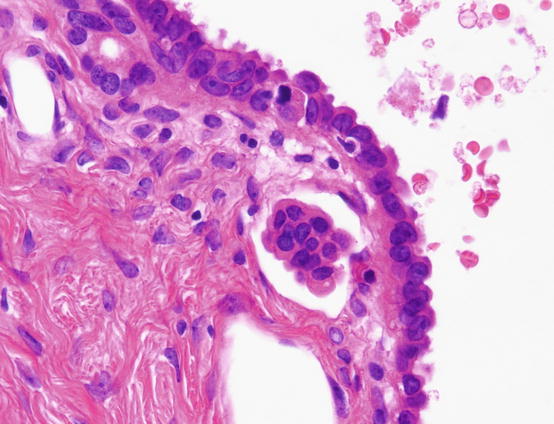

Fig. 5.6

Microinvasion of serous borderline tumor. A small cluster of eosinophilic cells is seen in the stroma

5.4.2.4 Extraovarian Spread of Serous Borderline Tumor

Peritoneal Implants

Peritoneal lesions of SBTs are found in 30–40% of ovarian SBT/APTs and have been called as implants. Histologically, implants are classified into noninvasive or invasive implants [27, 28]. Noninvasive implants show well-circumscribed proliferation of epithelium limited to the surface of peritoneum or septa of the omental adipose tissue. According to the absence or presence of the desmoplastic reaction, noninvasive implants are further classified into “epithelial-type” and “desmoplastic-type” implant. Invasive implants are characterized by haphazard, destructive infiltration of tumor cells into the underlying structure. Solid cell nests or papillae in the stroma with surrounding retraction artifacts and micropapillary proliferation are also considered to be invasive implants by some pathologists [27, 28]. SBTs/APTs with invasive implants should be diagnosed as LGSCs, since their clinical behaviors resemble each other.

Lymph Node Involvement

Lymph node involvement (LNI) has been reported in about 30% of SBT/APT patients who have undergone lymph node dissection. Mostly, LNI presents as isolated cells, cell clusters, small papillae, papillae, or cribriform glands. LNI as simple cysts composed of single layer of tubal type cells is termed endosalpingiosis. The presence of LNI does not affect the clinical course. Rarely, LGSC-like lesions replace nodal parenchyma, and such cases should be diagnosed as LGSCs.

5.4.3 Serous Carcinoma

Serous carcinoma is the most common type of ovarian carcinoma and accounts for more than 50% of ovarian cancers. According to Japanese statistics, 35% of ovarian malignancies are serous carcinoma. In the 4th edition of the WHO classification of ovarian tumors, serous carcinoma is subclassified as LGSC and HGSC. Since their histological features, molecular abnormalities, and precursor lesion are different, these two types of carcinoma are separated disease entities and not within the same disease spectrum. Rare cases of transformation of LGSCs to HGSC have been reported [29].

5.4.3.1 Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma

LGSCs are rare carcinomas that account for about 5% of all serous carcinomas. LGSCs are composed of tumor cells with low-grade atypia and low mitotic index (usually less than 12 per 10 high power fields). LGSC patients are typically younger than HGSC patients (mean, 41.7 years vs. 55 years) [30]. An association between 60 to 80% cases of LGSCs and usual and/or micropapillary SBT/APTs supports the theory that SBT/APTs are precursor of LGSCs [30–32].

LGSCs resemble SBTs/APSTs macroscopically. Histologically, LGSCs show characteristic invasive patterns such as micro- or macropapillae, or compact cell nests surrounded by clefts between the tumor cells and stroma. Less commonly, cribriform, glandular and/or cystic, solid sheets with slit-like spaces or single cells are seen.

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are positive for ER, PR, WT1, and PAX8. Unlike HGSCs, LGSCs show wild-type p53 immunoreactivity and a negative/patch pattern of p16 expression [23].

Differential diagnosis of LGSCs includes SBT/APT with microinvasion and HGSC. Distinction between LGSCs and SBTs/APTs with microinvasion depends on the pattern and size of the invasive lesion. If each invasive focus shows LGSC-like invasive pattern and is less than 5 mm in size, a diagnosis of SBT/APT with microinvasive carcinoma should be made. It should be noted that some HGSCs show an invasive micropapillary pattern resembling LGSCs. In this situation, nuclear atypia and mitotic figure counts should be evaluated carefully. Immunohistochemical studies of p53 expression are useful since most HGSCs show an aberrant p53 expression pattern (see section of HGSCs), while LGSCs do not [23].

5.4.3.2 High-Grade Serous Carcinoma

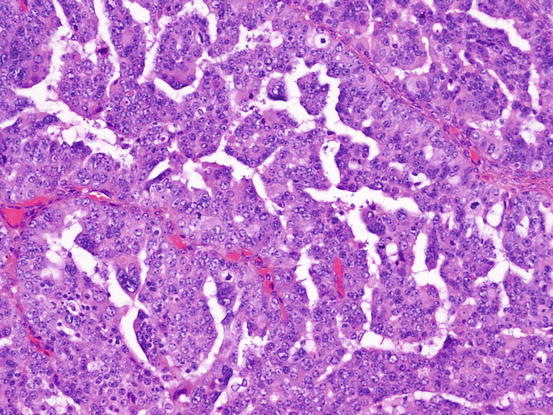

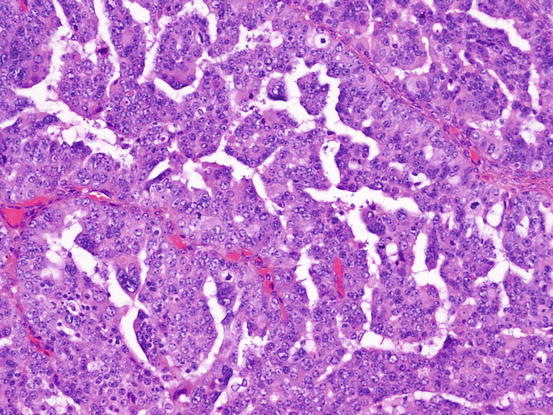

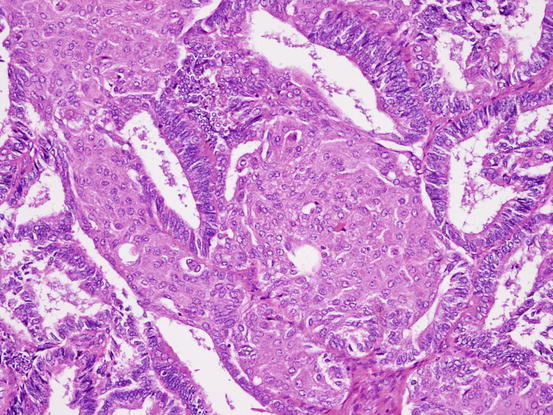

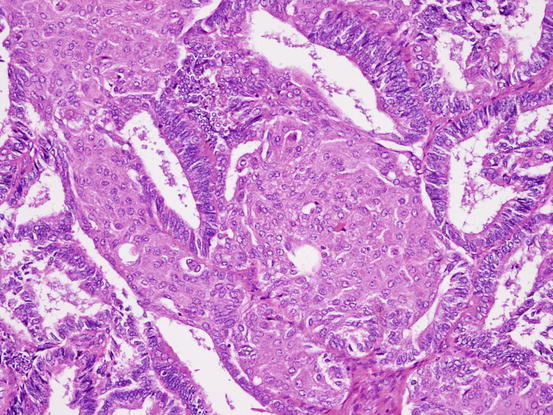

HGSCs show a predilection for older patients and are detected at an advanced stage. Macroscopically, HGSCs are solid, cystic, or mixed. Histologically, they show proliferation of highly atypical tumor cells with various histological patterns including solid, papillary, glandular, and transitional cell-like patterns (Fig. 5.7). Nuclei have coarsely vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Many mitotic figures are observed.

Fig. 5.7

High-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC). The tumor cells have highly atypical nucleus. Slit-like lumen is characteristic for HGSC

Thorough examination of fimbria reveals that about half cases of HGSCs are accompanied with serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.

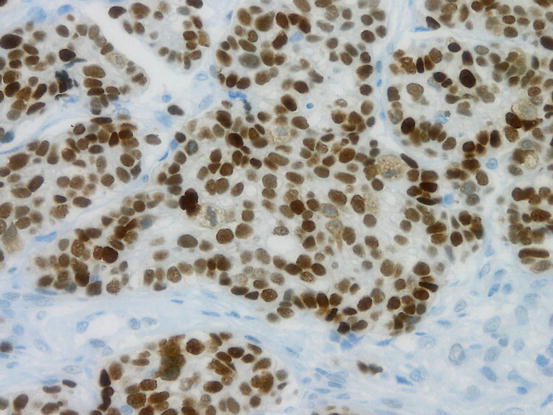

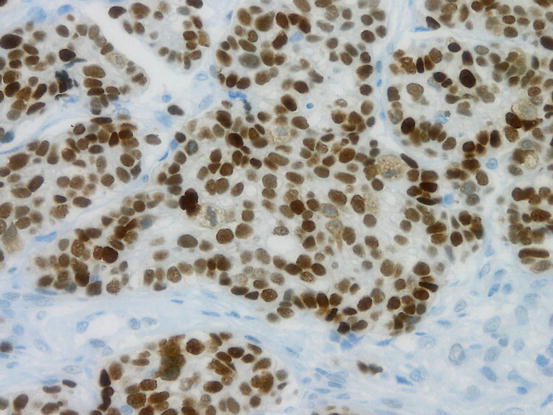

Immunohistochemically, HGSCs are positive for CK7 but negative for CK20. Most cases are positive for WT1 and PAX8 and show variable positivity for ER and PR. As most HGSCs harbor the TP53 mutation, the p53 protein expression pattern in HGSCs is diffuse and strongly positive (Fig. 5.8) or completely negative (“null”) [23].

Fig. 5.8

Aberrant p53 expression in high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC). Diffuse and strong positivity of p53 immunohistochemistry suggest mutation of TP53

Other types of ovarian cancers should be distinguished from HGSC. Some HGSCs show glandular proliferation of columnar cells and resemble endometrioid carcinoma, but HGSCs usually have aberrant p53 expression and are positive for WT1, while endometrioid carcinomas show a wild-type p53 immunostaining pattern and are WT1 negative. Sometime, HGSCs show papillary growth of clear cells, and, hence, clear cell carcinoma has to be included in the differential diagnosis. Differential diagnosis between HGSCs with clear cells and clear cell carcinoma is discussed in the section of clear cell carcinoma (please see Sect. 5.7.2 of this chapter).

5.5 Mucinous Tumors

Mucinous tumors are epithelial tumors composed of gastrointestinal-type mucinous epithelium. Goblet cells, Paneth cells, and neuroendocrine cells also appear in mucinous tumors. Previously, tumors with mucinous epithelium resembling the endocervix have been included among mucinous tumors. However, in the 4th edition of WHO classification, these are designated as seromucinous tumors.

Although mucinous tumors are more frequent in older patients, they are also more common in children and adolescents than other types of ovarian epithelial tumors.

Usually, mucinous tumors are large, multilocular cystic tumors. Most cases are unilateral. The tumor size is not associated with the malignant potential. Since the coexistence of tumor components of different malignancy is not unusual in mucinous tumors, careful gross observation and adequate sampling are keys to accurate histological diagnosis. Mucinous tumors less than 10 cm in greatest dimension require one section per 1 cm, but larger tumors or those with microinvasion or intraepithelial carcinoma require two sections per cm [33]. As most malignant components tend to be small cystic or solid, such area should be extensively sampled at the time of dissection.

5.5.1 Mucinous Cystadenoma/Adenofibroma

These tumors are composed of cyst of various sizes or glands lined with a single layer of columnar epithelium containing intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 5.9). Goblet cells are often observed. Mucinous adenofibromas contain solid fibrous stroma. Tumors with papillary proliferation of epithelium, which occupy less than 10% of the tumor, are classified into this category.

Fig. 5.9

Mucinous adenoma. Columnar epithelium with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin forms glands. Cellular atypia is mild

5.5.2 Mucinous Borderline Tumor/Atypical Proliferative Mucinous Tumor (MBT/APMT)

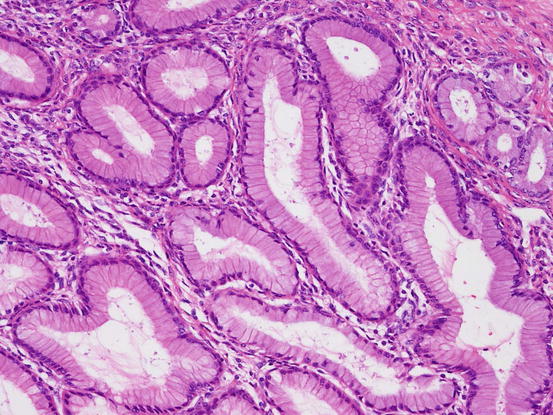

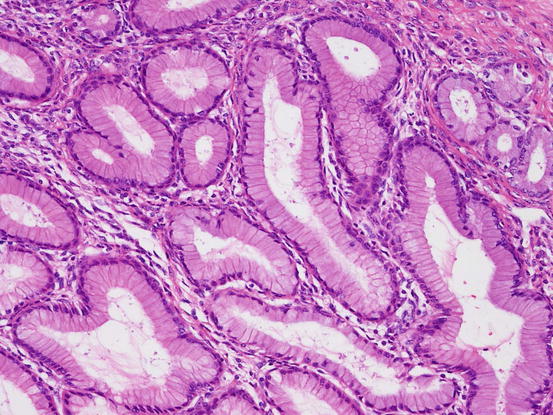

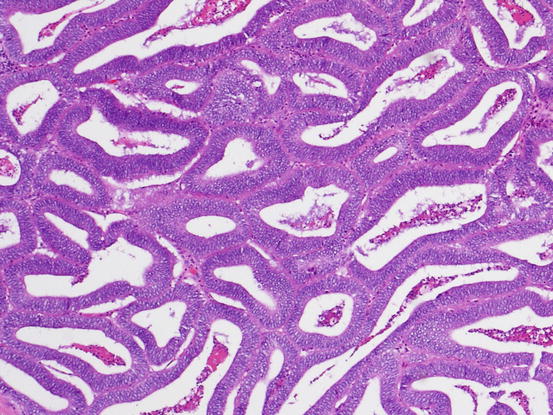

The characteristic feature of MBT/APMT is papillary proliferation of epithelium associated with mild to moderate nuclear atypia (Figs. 5.10 and 5.11). Foci of marked cellular atypia in MBT/APMT are designated as intraepithelial carcinoma. Stromal invasion of less than 5 mm in maximal linear dimension is defined as microinvasion, and tumors with this feature are designated as MBT/APMT with microinvasion. In these tumors, the microinvasive component with marked cellular atypia is classified as microinvasive carcinoma. A tumor stage ≥IC, intraepithelial carcinoma, microinvasion, and patient age of less than 45 years are associated with tumor recurrence [34].

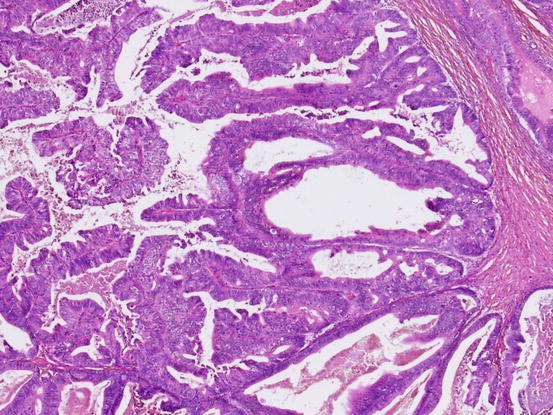

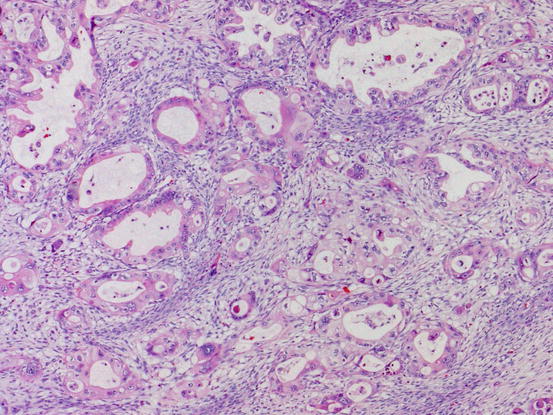

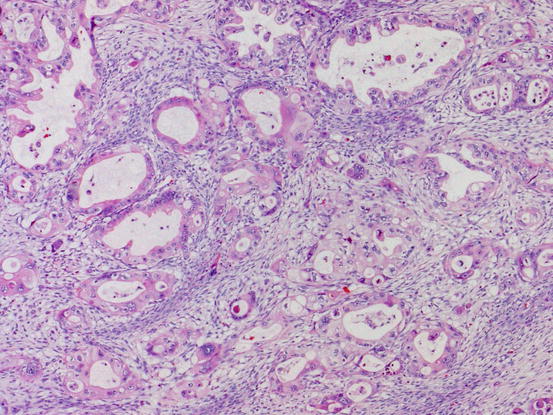

Fig. 5.10

Mucinous borderline tumor. The tumor shows complex papillary growth of mucinous epithelium

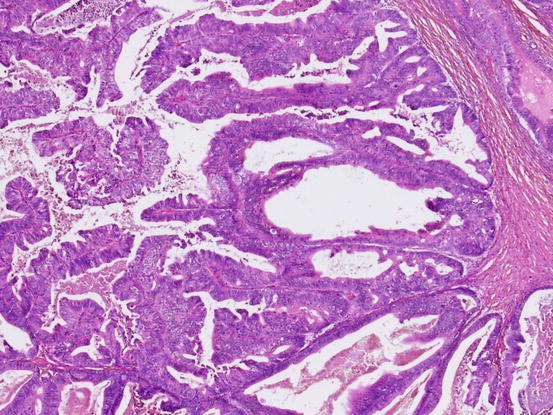

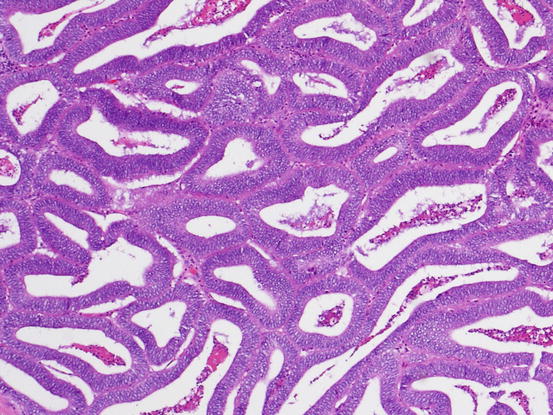

Fig. 5.11

Mucinous borderline tumor. In contrast to benign mucinous tumors (upper), tumor cells of borderline tumors (lower) show nuclear atypia that is short for diagnosis of carcinoma

5.5.3 Mucinous Carcinoma

Mucinous carcinoma is a malignant tumor, comprising of gastrointestinal-type mucinous epithelium. Mucinous carcinoma is usually unilateral, and advanced stage disease is rare [35].

Two types of stromal invasion are recognized for mucinous carcinoma: confluent invasion and destructive invasion. Confluent or expansile invasion (Fig. 5.12) is defined as marked glandular crowding or cribriform growth of mucinous epithelium with significant cellular atypia. Such an area should be larger than 5 mm to make a diagnosis of carcinoma. The destructive stromal invasive pattern (Fig. 5.13) is characterized by proliferation of glands with irregular shape in haphazard arrangement in usually desmoplastic stroma.

Fig. 5.12

Mucinous carcinoma with expansile invasion. Marked crowding of glands and severe nuclear atypia warrant the diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma

Fig. 5.13

Mucinous carcinoma with destructive invasion. Highly atypical mucinous glands proliferate haphazardly

Mucinous tumor cells are diffusely positive for CK7 and show variable positivity for CK20. Positivity of CDX2 expression also varies [36], while ER and PR are usually negative. PAX8 is positive in about half the cases [37]. A recent study showed that the expression of SATB2, a transcription regulator expressed in colorectal normal epithelium and carcinoma, is negative in primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma [38].

The most critical differential diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma is metastatic adenocarcinoma, especially of colonic or pancreatobiliary origin. Some metastatic adenocarcinomas are similar to primary ovarian mucinous tumors both macroscopically and microscopically. Bilaterality, small size (<10 cm), multinodular growth, hilar involvement, and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III or IV suggest metastatic carcinoma [39]. Although both histological and immunohistochemical findings may help differential diagnosis, there is overlapping immunoreactivity [40]. For accurate diagnosis, histological findings, as well careful search of medical history, are essential. Even with no history of carcinoma, a systemic workup is highly recommended for patients whose tumor shows histological features characteristic of metastatic tumors.

5.5.4 Mucinous Tumor with Mural Nodule

MBTs/APMTs or mucinous carcinomas rarely have well-demarcated mural nodules. Histologically, three types of mural nodules have been described: reactive sarcoma-like mural nodules (SLMNs), anaplastic carcinoma, and sarcomatous nodules. Different types of mural nodules may be seen in a single tumor. SLMNs are composed of epulis-type giant cells, atypical spindle cells, and inflammatory cells. The SLMN cells are weakly/focally positive for cytokeratin and positive for vimentin and CD68. Mucinous tumors with SLMN are almost always detected in stage Ia, and the prognosis is favorable [41]. Anaplastic carcinomatous nodule shows sheet of highly atypical rhabdoid, spindle, or pleomorphic epithelial cells. In contrast to SLMN, anaplastic carcinoma cells are definitely positive for cytokeratin. Although the prognosis of mucinous tumors with anaplastic carcinomatous mural nodules is favorable in unruptured stage Ia cases, these tumors are often associated with extraovarian spreading, which usually predicts a poor prognosis [42]. Sarcomatous nodules may appear as fibrosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, or undifferentiated sarcomas.

5.6 Endometrioid Tumors

Endometrioid tumors are defined as tumor with proliferation of endometrial-like epithelium. Most endometrioid tumors are malignant—benign and borderline endometrioid tumors are quite rare.

5.6.1 Benign Endometrioid Tumor

In the 4th edition of the WHO classification, endometriotic cysts are classified as benign endometrioid tumors. Endometrioid cystadenomas and adenofibromas show proliferation of endometrial-type epithelium without endometrial-type stroma.

5.6.2 Endometrioid Borderline Tumor/Atypical Proliferative Endometrioid Tumor

Endometrioid borderline tumors/atypical proliferative endometrioid tumors (EBTs/APETs) show intracystic or adenofibromatous growth. Tumor glands with mild to moderate cellular atypia show fused or confluent proliferation. Squamous differentiation or morula formation is not uncommon. By definition, borderline tumors lack more than 5 mm of confluent or infiltrative growth of the glands.

5.6.3 Endometrioid Carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinomas display proliferation of endometrial gland epithelium. Coexistence of endometriosis or endometriotic cysts has been reported in 9 to 70% of cases. Peak incidence is in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Uterine endometrial endometrioid carcinomas coexist in 15–20% of patients with ovarian endometrioid carcinoma [43].

A typical endometrioid carcinoma has confluent glandular, cribriform, and papillary proliferation of columnar cells (Fig. 5.14). Destructive infiltrative growth is also seen. Squamous differentiation is seen in 30–50% of cases. Squamous components are often in the form of morules (Fig. 5.15). The secretory variant of endometrioid carcinoma is characterized by cytoplasmic sub- and supranuclear vacuoles resembling early secretory phase endometrial glands. Ciliated variant is characterized by cilia on the luminal surface of the tumor cells. Oxyphilic variant has cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and centrally located nucleus. Spindle cell variants display proliferation of spindle-shaped epithelial cells. Occasionally, endometrioid carcinoma shows trabecular or small glandular pattern resembling sex cord tumors such as adult-type granulosa cell tumors or Sertoli cell tumors.

Fig. 5.14

Endometrioid carcinoma. Well-formed glands with columnar cells show confluent growth without intervening stroma

Fig. 5.15

Endometrioid carcinoma. Morula occupies the lumen of glands

Endometrioid carcinoma cells express cytokeratin, vimentin, ER, and PR. Tumor with a CTNNB1mutation shows nuclear localization of β-catenin. About 30% of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas harbor the ARID1A gene mutation and show loss of BAF250a immunoreactivity [12]. Some carcinomas histologically resembling endometrioid carcinoma show aberrant p53 expression. Such tumors, especially in association with WT1 expression and high-grade atypia, should be diagnosed as HGSCs [44].

When ovarian endometrioid carcinoma is associated with uterine endometrioid carcinoma, differential diagnosis whether ovarian tumor is primary or metastatic is important. Diagnostic criteria including several factors such as tumor size, laterality, depth of invasion of uterine myometrium, background lesions (e.g., endometriosis in ovaries, atypical endometrial hyperplasia in endometrium), and molecular abnormalities have been proposed [43].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree