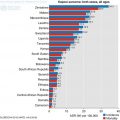

Fig. 4.1

Healthcare spending as percentage of GDP

Fig. 4.2

Healthcare spending as percentage of total government expenditure

There is extreme shortage of pathologists in SSA. The tertiary institutions with accreditation for providing training of specialist pathologists are few, training is highly variable, training time tends to be short because of the high cost and structured programs are lacking in many countries (Benediktsson et al. 2007). These trainees are often eager to leave the countries in SSA for one of the developed nations of the world. They leave because of a lack of infrastructure to practice, lack of conducive environment and good working conditions, poor remuneration and thus become part of the ‘brain drain.’

In Nigeria, only 6% of 3056 practicing specialist physicians are pathologists. According to the data from the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN), only 182 of 380 pathologists (58%) are practicing in Nigeria, the remaining 52% are lost to brain drain. When medical graduates or fellows travel for additional training in foreign countries, the difficulties with applying the new skills acquired to their practice on their return to the home country may encourage them to stay back in the developed nations where they acquired these skills. The pathologist’s role is not properly understood and this lack of recognition for pathology is not only seen among the general public but also among clinical colleagues, administrators and politicians who are at the forefront of developing policies for health in the various countries.

This deplorable situation of poor pathology services in SSA represents deterioration from the high standards that were in existence in many institutions in the early 1950s to the 1970s, during which period pathology services were comparable to the developed world (Adeyi 2011). Burkitt lymphoma, for example, was first described by Denis Burkitt, an Irish Surgeon based in Africa. Subsequent research on the pathogenesis of this disease was conducted on the Raji cell line produced from a health facility in Africa (Burkitt 1958).

The challenges to the provision of pathological services in SSA are enormous. They are not limited to poor funding and shortage of personnel alone; they also include inadequate infrastructure, laboratory facilities and equipment, facilities for data management and processing etc. Standard operating procedures, external and internal quality assurance schemes, facilities for shipping of specimens to reference pathology centres are important militating factors (Fitzgibbon and Wallis 2014).

There have been several efforts at addressing the myriad of problems confronting pathology practice in SSA particularly as it relates to cancer diagnosis and management. In 2013, the African Pathologists Summit under the auspices of African Organization for Research & Training in Cancer (AORTIC) in collaboration with several other organizations within and outside of Africa, held a meeting in Dakar, Senegal, with the main objective of identifying the constraints to pathology services and to find the avenues to addressing these constraints. It was noted that there is significant lack of professional and technical personnel, inadequate infrastructure, limited training opportunities, poor funding of pathology services and these have significant impact on patient care. Recommendations (discussed below) for urgent action were made in order to tackle these challenges (African Pathologists’ Summit Working Group 2015).

At the African Pathologists Summit, it was agreed that pathologists in SSA must come together to leverage upon the available resources by encouraging local and international collaborations for pathology. A consensus was reached to use specific strategies in tackling the issues affecting pathology practice in SSA including the improvement of diagnostic service, the establishment of regional training centers and the development of clinical and translational research that will provide information critical for policy making decisions.

The major pathology services provided in most SSA for cancer diagnosis and management are: surgical pathology and histochemistry, cytopathology (both gynaecological and non-gynaecological). Only a few centres have facilities for providing frozen sections, histochemistry, immunohistochemistry, and molecular pathology on a routine basis.

4.2 Pathology Tissue Handling and the Challenges Faced in the Various Sub-sections

4.2.1 Histopathology/Surgical Samples

In SSA, this diagnostic procedure serves the purpose of providing a diagnosis, staging and grading and guiding clinical management including surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The use of the appropriate fixative for the preservation of tissues obtained at surgery as well as the cold ischaemia time is of importance as is the duration of fixation. The sample should be immersed in preservative as soon as it is removed, and not at the end of the surgical procedure. A container that is large enough to contain the sample as well as a volume of preservative that is at least 10 times the volume of the sample should be used. In breast cancer, the ratio of tissue/fixative of 1:20 was recommended and the sample must be placed in fixative within 1 h of removal. For breast specimens, the sample must remain in the fixative for no more than 8 h (Yaziji et al. 2008). Improper fixation and long cold ischaemia time have negative effects on the preservation of DNA.

The most commonly used fixative is 10% buffered formal saline (formalin) which is suitable for all tissues, it is cheap and easy to prepare. Paraffin-embedded tissue processing and staining using routine haematoxylin and eosin stains is provided by the pathology laboratories in most centres in SSA. Proper tissue processing can be done with manual, semi-automated or fully automated tissue processors. Manual tissue processing is the most prevalent in SSA due to a lack of availability of the tissue processing machine. This may result in the tissue becoming overly processed (‘fried’ or ‘cooked’ tissue). Sometimes poor quality paraffin wax is supplied for use at the laboratory since, in many countries; the procurement of laboratory consumables is done by non-technical personnel. This issue is further compounded by poor storage facilities of these consumables due to erratic power supply. Inappropriate tissue processing and poor facilities for storage and archival of tissue blocks and histopathology slides constitute major obstacles to conducting cancer research in many parts of SSA. In a molecular study investigating the incidence of K-RAS and BRAF mutations among patients with colorectal cancers in Nigeria, a high failure rate of 112 of the 200 cases (56%) of pyrosequencing was recorded and this was attributed to poor fixation of the tissues (Abdulkareem et al. 2012).

Pathology services in most parts of SSA are concentrated in major cities and therefore transportation of samples to these centers from remote areas remains a challenge, with these services being largely inaccessible to the rural areas. Poor road networks and difficulties with finding the funds to pay for transportation contribute to this problem. Where these samples are sent to the laboratories with pathologists, the Turn Around Time (TAT) is prolonged by the delay between obtaining the specimen and depositing it at the laboratory, the time lag being that required for transportation. Nelson et al. reported that the case loads of surgical samples processed each year ranged from less than 100 in Burundi to >20,000 in Nigeria, Kenya and >40,000 per year in South Africa while TAT ranged from 1–3 days to as long as 21–28 days in some countries (African Pathologists’ Working Groups 2015). They reported that there is statistically significant correlation between the number of pathologists and histotechnologists and the case load but TAT was inversely correlated and not significant.

In order to standardize practice, The AORTIC Pathology Summit has therefore recommended step-by-step process of tissue handling from specimen acquisition, processing to final reporting as shown in the Table 4.1 below (Fitzgibbon and Wallis 2014).

Table 4.1

Step-by-step-tissue handing for surgical histopathology (Modified from the African Pathologists Summit 2015)

Specimen collection, labelling, consultation request | Specimen processing | Reporting |

|---|---|---|

Standard operating procedure for collection, identification and fixation | All specimen should be grossed and processed on the day of arrival except if not fixed | Synoptic reporting with paper template or use of software |

Standardized requisition form should have among others patient identification, specimen source, anatomic markings, clinician contact information | Grossing station would be well ventilated and have a digital camera | Distribute reports promptly as appropriate |

10% buffered formalin should be supplied by the pathology department If preservation quality is unknown, fixative should be changed in the laboratory

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|