used throughout this chapter. Disease-specific formulas were developed to address the particular needs of patients with renal, cardiac, or hepatic disease and became commercially available. Multiple organizations, such as the Oley Foundation and hospital-based support groups, grew out of need for the rehabilitation of patients surviving catastrophic illnesses by maintenance on home parenteral nutrition (HPN). PN has evolved into a sophisticated field of therapeutic intervention that has its own multidisciplinary specialists and a large body of established knowledge.

EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

Reduced morbidity and mortality with enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critical care units

Use of practice guidelines for nutritional support in different care settings

Usage of glutamine (an amino acid)

Trials of designer lipid emulsions, for example, soybean oil (SO), medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), olive oil (OL), and fish oil (FO)

Infusion-related support for PN: administration set changes, dressing guidelines, prevention of infection and extravasation, rate of infusion, and thrombosis prevention

<600 mOsm and the final concentration of dextrose 10% or lower. Solutions with an osmolarity >600 mOsm are known to cause phlebitis. Typically, PPN is given for 7 days or less. It is not intended for prolonged nutrition support. It is also not appropriate for patients who cannot tolerate large volumes of fluid. Risk versus benefit must be weighed before the decision to treat with PPN is made. Strategies to reduce the risk of phlebitis should be implemented if PPN is selected as a course of treatment:

Addition of a steroid such as hydrocortisone to the solution

Addition of heparin

Concomitant administration of fat emulsion

Infusing the solution using a cyclic schedule such as infusing over 12 hours per day (INS, 2011)

TABLE 16-1 EFFECTS OF MALNUTRITION | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Starvation-related malnutrition where there exists a chronic state of malnutrition without inflammation. Anorexia nervosa is an example of this type.

Chronic disease-related malnutrition exists when there is a chronic state of mild to moderate inflammation. Examples of this type are pancreatic cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic renal failure, and in obesity with loss of muscle mass.

Acute disease- or injury-related malnutrition that occurs with acute, severe inflammation. This type of malnutrition occurs in conditions such as trauma, burns, sepsis, head injuries, and acute inflammatory bowel disease (Jensen et al., 2010).

Major trauma

Radiation enteritis

TABLE 16-2 POTENTIAL INDICATIONS FOR PN FOR PATIENTS IN THE ICU

If the patient in the ICU was healthy and nourished prior to ICU admission, PN is initiated after the first 7 d of hospitalization when EN is not available.

Evidence from Casaer et al. (2011); McClave et al. (2009)

If the patient is protein-calorie malnourished on ICU admission and EN is not feasible, PN is initiated as soon as possible following admission and adequate resuscitation.

Evidence from McClave et al. (2009)

“If a patient is expected to undergo major upper GI surgery and EN is not feasible, PN should be provided under very specific conditions” which accounts for the ICU patient’s nutritional status (malnourished), when surgery is anticipated (5 d are available to start PN), and how long the PN therapy is expected to last (more than 7 d).

Evidence from McClave et al. (2009)

If the patient intake is unable to meet energy requirements (100% of target goal calories) after 7-10 d by the EN, initiate supplemental PN.

Evidence from McClave et al. (2009)

Severe diarrhea

Pancreatitis when EN is not tolerated

Extensive burns

Acute abdomen or ileus

GI hemorrhage

Ischemic bowel disease

Bowel obstruction

Severe short bowel syndrome

Inflammatory bowel disease

Enterocutaneous fistula

Intractable nausea/vomiting

Daily surgeries planned

Severe mucositis

Aggressive attempt at EN failed

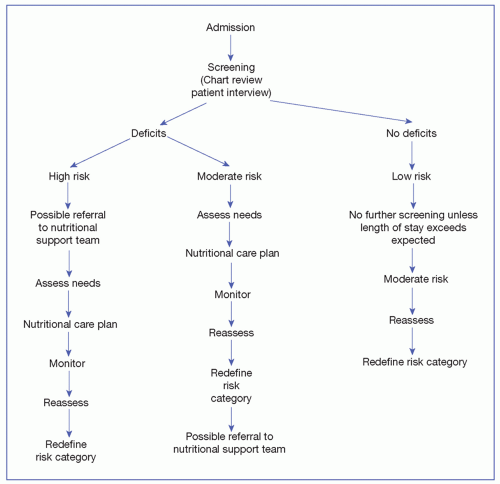

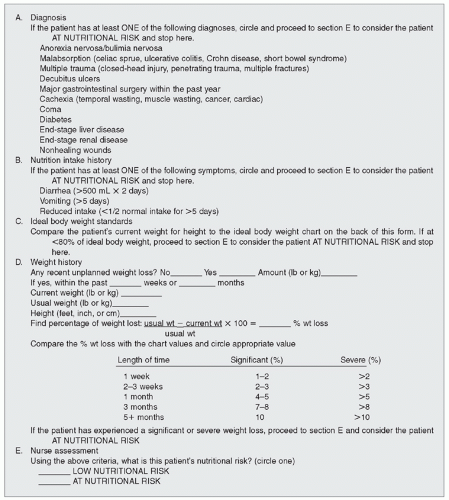

assessment is indicated. In the United States, The Joint Commission (TJC) identifies a standard to screen nutrition within 24 hours of admission to an acute care center. The goal of nutrition assessment is to identify any specific nutrition risk(s) or clear existence of malnutrition. Nutrition assessments may identify recommendations for improving nutrition status (e.g., an intervention such as change in diet, enteral or parenteral nutrition, or further medical assessment) or a recommendation for rescreening (Mueller, Compher, Druyan, & American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors, 2011). Nutrition assessment has been defined by A.S.P.E.N. as “a comprehensive approach to diagnosing nutrition problems that uses a combination of the following: medical, nutrition, and medication histories; physical examination; anthropometric measurements; and laboratory data” (Mueller et al., 2011). A nutrition assessment provides the basis for a nutrition intervention. A focus on mandatory screening and nutritional assessment as part of the specific nutritional care standards began with TJC in 1995. The standards emphasize an interdisciplinary approach. In many settings, the nutritional screen is completed by a health professional other than the dietitian. The goal of nutritional screening is to identify individuals who are at nutrition risk, as well as to identify those who need further assessment.

To identify individuals who require aggressive nutritional support

To restore or maintain an individual’s nutritional status

To identify appropriate medical nutrition therapies

To monitor the efficacy of these interventions (Hammond, 2004)

certain medications, and social factors also have an impact on nutritional status and should be evaluated. Multiple computerized programs for dietary assessment are available, each providing different end points of data (Probst & Tapsell, 2005). Benefits of a computerized assessment include standardized questioning, immediate micronutrient information, and possible recommendations; additionally, these programs may be used for practice or research. Specific factors that may alter nutritional status are listed in Box 16-1.

in evaluating for overnutrition or undernutrition. The patient’s actual height and weight should be obtained and used to help determine nutritional status.

weight are entered. This information may be part of the clinical decision support system and provide an automatic consultation to the dietitian for specific BMI parameters indicating that a patient is at nutritional risk. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also provides a Web site for calculating BMI for adults and children: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi.

TABLE 16-3 PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT FINDINGS IN NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCIES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

conditions, and function of the GI tract” (McClave et al., 2009). Traditional anthropometric measures are not validated in critical care (McClave et al., 2009).

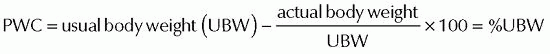

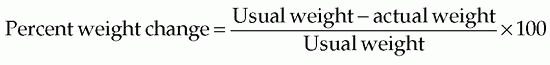

TABLE 16-4 ESTIMATING BODY WEIGHT AND PERCENTAGE LOSS IN PN | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 16-5 VISCERAL PROTEINS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

the oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production of the body over a period of time. This helps to determine actual energy expenditure. Indirect calorimetry requires expensive equipment and therefore is not available at all institutions (Hammond, 2004).

expenditure in the nonobese population, whereas only 21 kcal/kg body weight is needed in the obese critically ill population (Rychlec, Edel, Murray, Schurer, & Tomko, 2000).

TABLE 16-6 CORRECTION FACTORS FOR ESTIMATING NONPROTEIN ENERGY REQUIREMENTS OF HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Environmental factors such as specialized high-air-loss beds, ultraviolet light therapy, and radiant warmers also increase fluid requirements. Humidified air reduces insensible fluid loss and results in lower fluid requirements. Preexisting excess or deficiency states and cardiac and renal function must also be evaluated.

PATIENT SAFETY

PATIENT SAFETYStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree