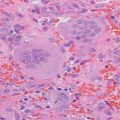

Fig. 9.1

Nuclear medicine parathyroid single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) revealing increased sestamibi uptake in the inferior thyroid lobes bilaterally (arrows)

Assessment and Diagnosis

The classical medical mnemonic of the “3 Ps” identifies the pancreas, pituitary, and parathyroid glands as the major organ systems affected in MEN-1. Among these, PHPT is the most common manifestation and occurs in 88–97 % of MEN-1 patients [1]. In contrast, only 4–5 % of patients with sporadic PHPT are subsequently diagnosed with MEN-1 [2]. PHPT is usually the initial clinical feature found in patients with MEN-1 and typically presents by the third or fourth decade of life [1, 3]. Current international guidelines recommend annual assessment of serum calcium and PTH levels in known MEN-1 patients as a screening measure [4].

Asymmetric, multi-gland parathyroid disease is the norm in these individuals [3, 5–7], and therefore, management can be more complex than in patients with sporadic, single-gland PHPT. In the past, the multi-gland nature of PHPT in MEN-1 was thought to be due to circulating humoral factors that led to diffuse parathyroid hyperplasia [8, 9]. This belief has shifted over the years, and it is currently believed that parathyroid growth in MEN-1 is a neoplastic process which results in the development of multiple parathyroid adenomas [1, 5, 8]. Based on this multi-gland nature, preoperative imaging for adenoma localization is rarely indicated and of limited benefit [4].

The main treatment for PHPT in MEN-1 is surgical removal of hyperfunctioning glands. Eliminating PHPT in these patients will reduce the risk of nephrolithiasis and fractures and has been shown to improve quality of life [3]. Individuals with concurrent gastrinoma have even been found to have reduced gastrin levels after parathyroidectomy due to lower serum calcium levels [10]. The optimal surgical strategy for parathyroidectomy in MEN-1 patients remains controversial [1, 3, 6, 11–13].

Surgical options include subtotal parathyroidectomy (subPTX; removal of 3 or, more commonly, 3.5 parathyroid glands) or total parathyroidectomy (totPTX) with autotransplantation. Most experienced endocrine surgeons would also suggest that a transcervical thymectomy be included with any parathyroid operation in patients with MEN-1 [7, 14–16]. Both subPTX and totPTX have inherent challenges and are best performed by experienced parathyroid surgeons. The major risk for subPTX is recurrent or persistent hyperparathyroidism and is reported to occur in 16–54 % of patients within 5–10 years after surgery [1, 7, 12]. Leaving a small remnant (<40 mg) of normal-appearing parathyroid tissue is optimal, but with a disorder named “Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia,” it is no surprise that recurrent PHPT may occur over years of follow-up as the remnant enlarges. Total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation on the other hand may lead to permanent hypocalcemia in up to 30 % of patients [12, 17]. A completely aparathyroid state is unnatural and requires dutiful calcium supplementation with careful medical follow-up. Conversely, some MEN-1 patients with transplanted parathyroid tissue may actually develop recurrent PHPT as the transplanted tissue enlarges over time.

In a 2011 systematic review and meta-analysis, Shreinemakers and colleagues assessed the optimal surgical approach for PHPT in MEN-1 patients. Based on their own experience at a single center and 12 additional studies over a 42-year period, they found that patients undergoing anything less than subPTX (i.e., one- or two-gland parathyroidectomy) had a significantly higher risk of developing recurrent and persistent PHPT compared to subPTX or totPTX (OR 3.11, 95 % CI 2.00–4.84) [3]. Those that underwent subPTX were then compared to totPTX patients; there were no major differences in rates of recurrent and persistent PHPT between these two groups. Patients who received subPTX did, however, have a lower risk of permanent hypoparathyroidism (OR 0.25, 95 % CI 0.11–0.54) [3]. Based on this work, the authors preferred the use of subPTX in MEN-1 patients over all other surgical options. A more recent randomized-controlled trial involving 17 patients with subPTX vs. 15 patients with totPTX and parathyroid autotransplantation suggests there are no differences between these two approaches when performed by experienced surgeons in a standardized fashion [15]. The authors note, however, that the totPTX group had a longer aparathyroid state while the autografts regained function.

Based on this literature and our own long-term experience with MEN-1 patients, our practice relies on (1) bilateral neck exploration, (2) visualization of four or more parathyroid glands, (3) cervical thymectomy, (4) removal of 3.5 parathyroid glands (subPTX), and (5) consideration for parathyroid autotransplantation (into strap muscles or subcutaneous fat of the upper chest) if the remaining remnant’s blood supply is threatened. All four parathyroids should be identified and assessed for abnormality before any are resected. The smallest and most normal-looking gland (gross appearance) is utilized for the remaining remnant; it is ideal if it is an inferior gland and tacked to the trachea away from the recurrent laryngeal nerve. We prefer this approach for most patients with MEN-1 undergoing initial surgery for PHPT. Preoperative imaging for localization is occasionally utilized in very young patients.

Management

Our patient underwent subPTX with full four-gland exploration, cervical thymectomy, and three-gland parathyroidectomy (left inferior [230 mg], right inferior [830 mg], and right superior gland [380 mg]). The left superior gland (visually appeared to be normal and less than 40 mg in size) was left intact on its viable blood supply. Her intraoperative PTH decreased from a baseline of 62.6 to 23 pg/mL at 10-min post-excision. Her PTH was 15 pg/mL on postoperative day number 1.

Seven years after her parathyroidectomy, the patient began to have symptoms of nausea, similar to what she experienced immediately after her pancreas surgery. No organic intra-abdominal cause was found. Laboratory studies revealed a serum calcium of 11.1 mg/mL. The PTH was found to be 58 pg/mL.

Etiologies for recurrent PHPT include heterogeneity in gland size at the index operation leading to insufficient resection [18], supernumerary or ectopic glands missed during the initial surgery, [6], and the progressive neoplastic potential inherent to remaining parathyroid tissue in MEN-1 patients [7]. The treatment for this frustrating situation in these patients is complicated and varies based on the surgical experience of each institution and surgeon, and especially the previous surgical intervention(s).

Options include reoperation, percutaneous alcohol ablation (PetA), and medical therapies. Success rates for reoperation in MEN-1 are highly variable [3, 7, 12, 16, 19], but reoperation does portend a greater risk for recurrent laryngeal nerve injury [3, 7, 16]. Unpublished data from our institution reveal that after the 2nd (or more) operation(s) for recurrent pHPT in patients with MEN-1, only 35 % are normocalcemic at 1-year follow-up. The use of PetA in the event of recurrence has been described with initial normocalcemia in 50–82 % of cases; however, persistent hypercalcemia was noted in up to 90 % of patients by 24 months [20, 21]. Finally, cinacalcet is well tolerated and appears to be effective in some case reports and small series [22–24], but long-term follow-up has been limited to a maximum of 60 months [22].

Our practice for MEN-1 patients with recurrent PHPT is to confirm the diagnosis with PTH, serum and urinary calcium levels, review the patient’s list of medications, and begin with localization studies – most commonly a nuclear medicine parathyroid single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). In patients with suspected findings of one hyperfunctioning residual/ectopic gland, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) with PTH washout can be performed in hopes of planning for a limited cervical reexploration with simple resection of the offending gland. Reoperative intervention is tailored based on imaging and biopsy results. Discovery of multiple enlarged glands (Fig. 9.2) likely warrants bilateral neck reexploration. While reoperation is our preference, patients with a history of multiple or difficult reoperations should be assessed for alternative strategies such as PetA or medical therapy. Although there is no optimal treatment, the final decision should be based on thoughtful and thorough discussions between experienced endocrine surgeons, endocrinologists, and the patient.