Fig. 17.1

Thyroid ultrasound of the right thyroid lobe shows a 4.6 × 2.1 × 2 cm (sagittal × anteroposterior × transverse) solid, hypoechoic nodule. This nodule is hypoechoic with taller-than-wide (anterioposterior/transverse diameter ratio >1) dimensions with microcalcification (white arrows) and low intranodular vascular flow by Doppler analysis (grade 3). (a) thyroid transverse view with Doppler. (b) Thyroid sagittal view. CA carotid artery, TRACH trachea

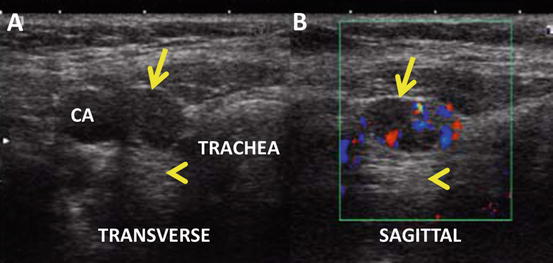

Fig. 17.2

Cervical node ultrasound. A 1.5 × 0.8 × 1 cm node (arrow) is located inferior to the thyroid in the right thyroid bed, cervical node level VI, between the carotid artery (CA) and the trachea. The node is partially cystic with post-cyst enhancement (arrowhead) and peripheral vascular flow in the solid component of the node. (a) Node transverse view. (b) Node sagittal view with Doppler analysis

Assessment and Literature Review

The risk of malignancy in a thyroid nodule rises with the sonographic appearance of microcalcifications (OR 6.4, 95 % CI 4.9–8.4), blurred margins (OR 4.8, 95 % CI 3.8–6.1), solid hypoechoic appearance (OR 3.8, 95 % CI 2.8–5.1), and taller-than-wide shape in the transverse image [1]. The likelihood of cancer is also very high when a nodal ultrasound survey reveals abnormal lymph nodes [2]. Sonographic features suggestive of metastatic lymph nodes include loss of the fatty hilum, a rounded shape, cystic change, calcifications, and peripheral vascularity [2].

It is recommended that thyroid nodules in pregnant women with euthyroidism and hypothyroidism be evaluated and biopsied with the same criteria as nonpregnant adults [3]. The 4.6 cm hypoechoic nodule was appropriately biopsied based on the high risk of malignancy by ultrasound criteria (solid, hypoechoic, taller-than-wide, microcalcification, abnormal nodes). The ultrasound appearance and a suspicious Bethesda class V cytology are both highly specific for malignancy, with an estimated median risk of malignancy of 70 % based on the meta-analysis reported by Bongiovanni et al. [4]. AJCC/TMN staging is a universal method of communicating extent of disease and correlates with risk of death. A 46-year-old female with a >4 cm papillary thyroid carcinoma with >1 cm metastatic level 6 nodes is at a minimum an AJCC/TMN classification stage 3 patient, but would be stage 1 in a typical young pregnant woman. The decision for surgery during pregnancy requires assessment of the risk of death and recurrence of the differentiated thyroid cancer balanced against the potential harm to the fetus.

There is no consensus to whether surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma should be performed during pregnancy or postpartum. While most retrospective analyses of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer diagnosed during pregnancy show that delaying surgery does not affect cancer outcomes [5], two other recent studies have shown that thyroid cancer diagnosed in pregnancy has a higher rate of persistence or relapse in the postpartum period [6, 7]. Although one large study showed that surgery performed during pregnancy has greater risk of complications and longer hospital stays [8], but did not provide data on fetal loss, other smaller retrospective studies show that it is safe during pregnancy, with no adverse fetal or maternal outcomes [9, 10]. These studies with fewer than 100 pregnant women show no difference in tumor stage (TMN), recurrence rate, complications of pregnancy, or adverse fetal outcome regardless of whether surgery is performed during or after pregnancy. The general recommendation is to avoid surgery during pregnancy if the tumor remains stable in size or is detected late in pregnancy. On the other hand, if the patient is older as in this case, or if the tumor has been documented to grow significantly or is associated with local or distant metastases, thyroidectomy is appropriate, preferably during the second trimester of pregnancy to avoid miscarriage [10].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree