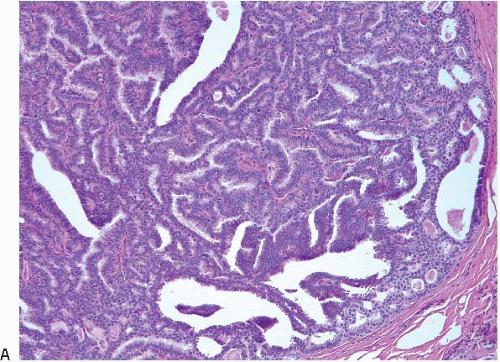

Papillary lesions of the breast comprise a heterogeneous group. These lesions have in common a growth pattern characterized by the presence of finger-like projections or fronds of variable length and thickness that are composed of central fibrovascular cores covered by epithelium. Although the histologic identification of a breast lesion as “papillary” is usually straightforward, the distinction among intraductal papilloma, papilloma with atypia (atypical papilloma), papilloma with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), papillary DCIS, or even invasive papillary carcinoma may be a source of diagnostic difficulty.

A few general principles apply to all papillary lesions. First, as will be discussed in more detail, assessment of the presence and distribution of myoepithelial cells in the lesion is one of the most helpful features in arriving at the correct diagnosis (

Table 8.1). In some cases, this may require the use of immunostains to myoepithelial cell proteins. Second, the ideal method to examine an excisional biopsy specimen containing a suspected intraductal papillary lesion involves carefully opening the involved duct longitudinally using a pair of fine scissors until the tumor is exposed. Identification of the lesion may be facilitated by the surgeon placing a suture at the end of the involved duct nearest the nipple. Randomly slicing through the excised tissue is not recommended as a small lesion may be missed. Third, if a papillary lesion is suspected on gross examination, a frozen section should not be performed because the distinction of benign from atypical or malignant papillary lesions on frozen sections may be extremely difficult. Moreover, freezing may produce tissue distortion and artifacts that could preclude definitive categorization of the lesion on permanent sections.

InTraDuCTal PaPIlloMa

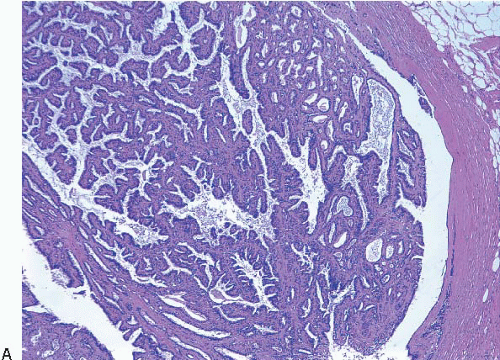

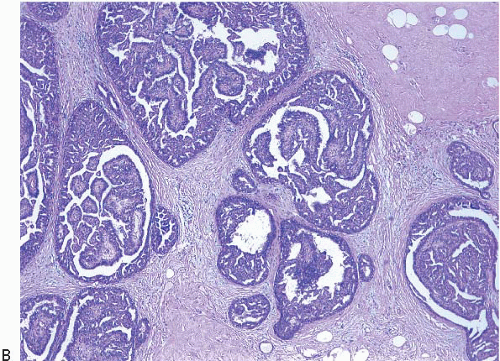

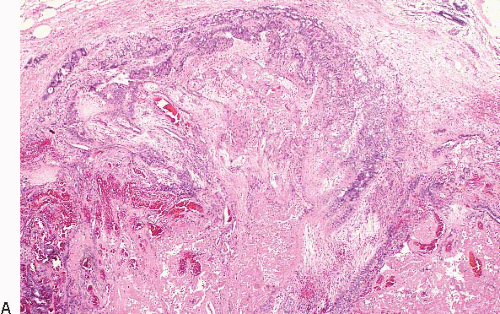

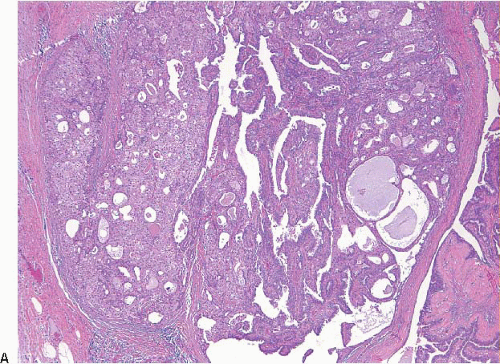

Intraductal papillomas are benign lesions that can be divided into two groups: central papillomas, which involve large ducts and are usually solitary, and peripheral papillomas, which involve the terminal duct lobular units and are usually multiple (

Fig. 8.1).

Central papillomas are tumors of the major lactiferous ducts and are most frequently observed in women 30 to 50 years of age. Patients usually present with nipple discharge that may be bloody; on occasion, the lesion reaches sufficient size to produce a palpable, subareolar mass. Peripheral papillomas occur in somewhat younger patients and less often present with nipple discharge or a mass.

1 They may occasionally present as a mammographic abnormality (microcalcifications or multiple densities).

Central papillomas are generally <1 cm in diameter, but occasionally may be as large as 4 or 5 cm. On gross examination, they appear as tanpink, circumscribed nodules within a dilated duct or cyst. A frankly papillary configuration may be apparent, but more typically the lesion has a bosselated surface. The tumor may be attached to the wall of the involved duct by a stalk or may be sessile. Peripheral papillomas are usually not identifiable on gross examination.

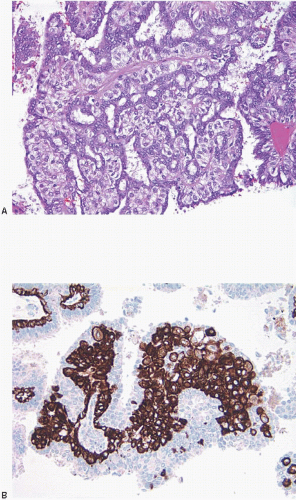

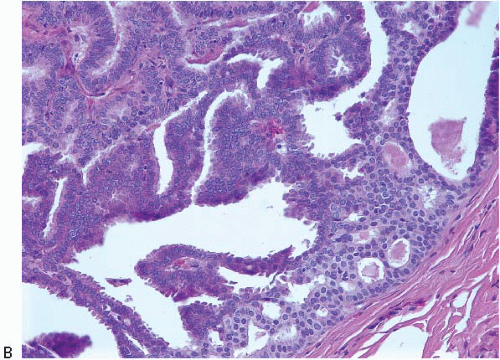

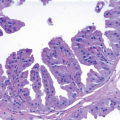

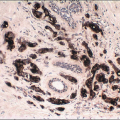

On histologic examination, papillomas are composed of arborizing fronds with well-developed fibrovascular cores (

Fig. 8.1,

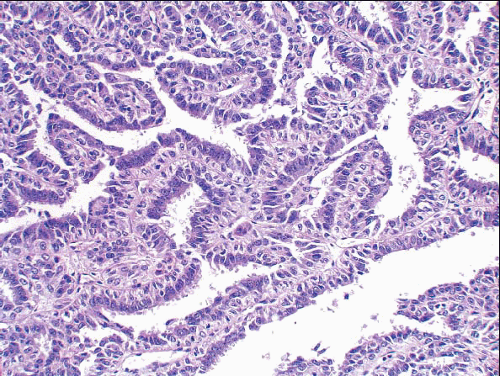

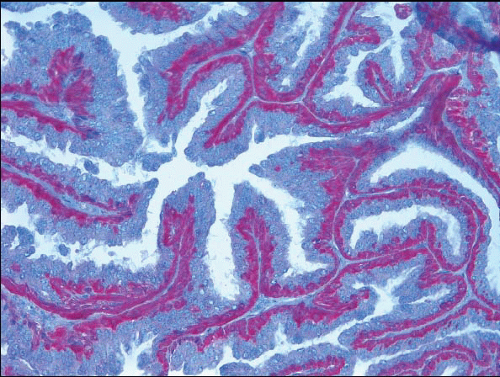

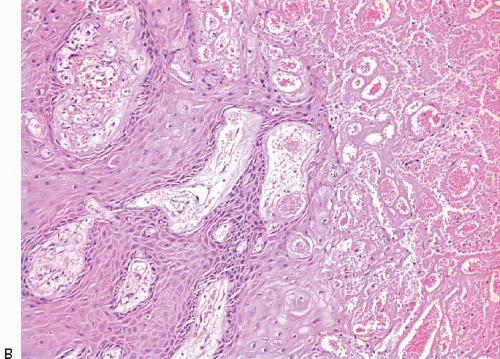

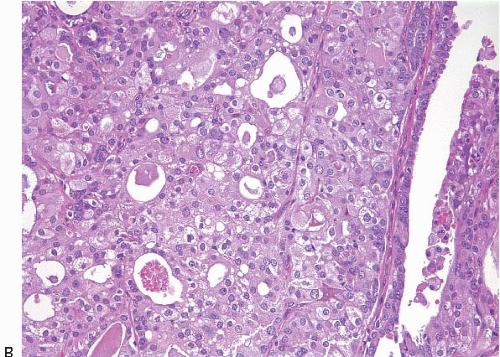

e-Fig. 8.1). The papillary fronds are covered by an inner myoepithelial cell layer and an outer epithelial layer (

Fig. 8.2,

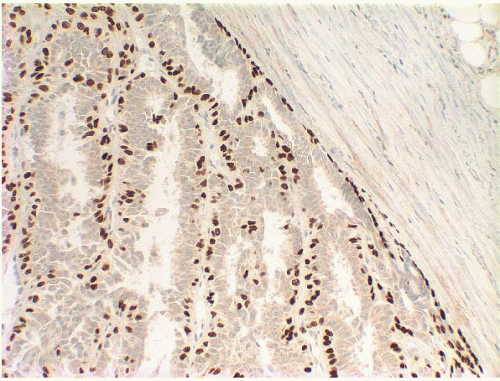

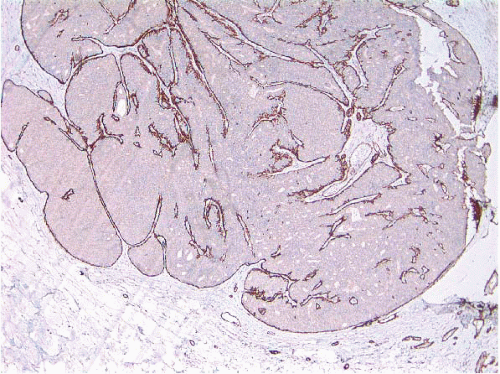

e-Fig. 8.2). The myoepithelial layer is variably prominent, but is always present. In problematic cases, myoepithelial cells can be highlighted by immunostaining for actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, calponin, p63, or other myoepithelial cell markers (

Fig. 8.3,

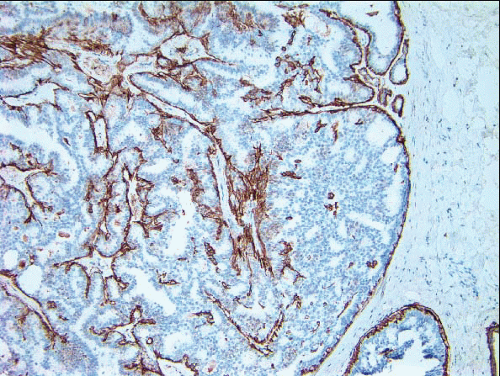

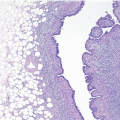

e-Fig. 8.3). Myoepithelial cells are also present at the periphery of the involved duct(s) (

Fig. 8.4,

e-Fig. 8.3) (

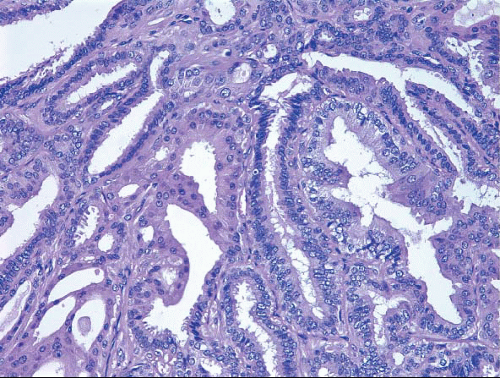

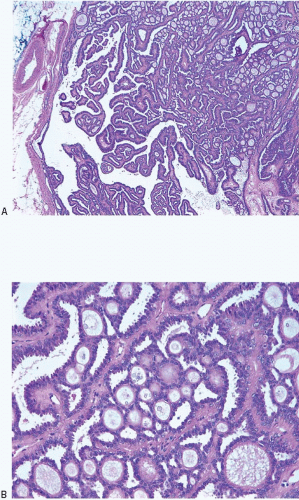

Table 8.1). The epithelium of benign papillomas may consist of one or a few layers of cuboidal to columnar cells or it may show varying degrees of usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH). The epithelial hyperplasia may be extreme and may grow in a contiguous fashion between adjacent papillae (

Fig. 8.5,

e-Fig. 8.4). In some cases, the epithelial proliferation may in areas have the appearance of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) or DCIS (see subsequent text). Apocrine metaplasia is frequent (

Fig. 8.6,

e-Fig. 8.5); squamous metaplasia may also be seen.

2 Varying degrees of myoepithelial hyperplasia may be observed in some cases (

Fig. 8.7). The hyperplastic myoepithelial cells can be epithelioid or spindle-shaped and may have abundant clear cytoplasm. The myoepithelial cell component may be sufficiently prominent that the foci resemble areas of adenomyoepithelioma (

e-Fig. 8.6) (see subsequent text). Collagenous spherulosis is yet another change that may be seen in the epithelium of intraductal papillomas; this should not be misinterpreted as an area of ADH or DCIS (

Fig. 8.8,

e-Fig. 8.7) (see subsequent text).

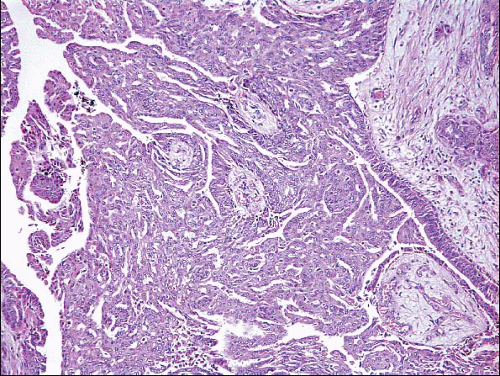

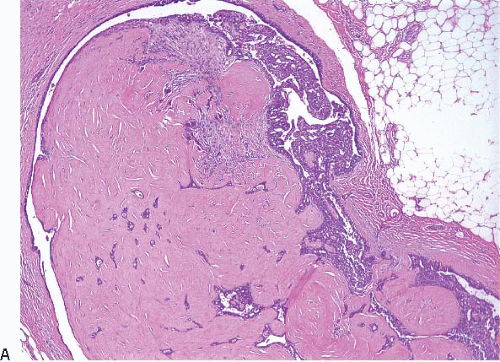

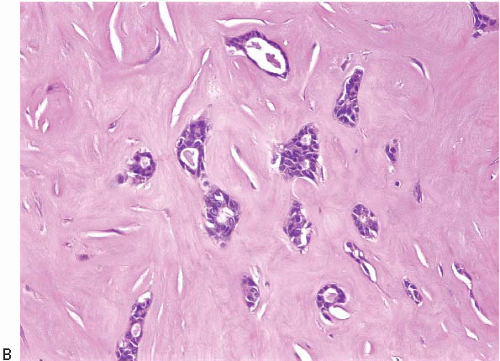

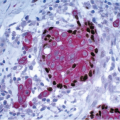

The papillary fronds and/or the surrounding duct wall may show varying degrees of stromal fibrosis and may contain entrapped glands and/or solid epithelial cell nests. On occasion, the fibrosis is so extensive that it distorts or obscures the underlying papillary architecture. In such cases, the term

sclerosing papilloma is appropriate. In the most extreme cases, the features overlap with those of a ductal adenoma (see subsequent text) or complex sclerosing lesion. The presence of glands or epithelial nests within a fibrous stroma may produce a worrisome appearance that raises the question of an invasive carcinoma (

Fig. 8.9,

e-Fig. 8.8). However, in benign intraductal papillomas with sclerosis, myoepithelial cells are discernible around at least some of the entrapped glands and epithelial nests, which is a feature supporting the benign nature of this process. In addition, the stroma of these lesions typically has a more hyalinized, sclerotic appearance than the stroma associated with invasive carcinomas.

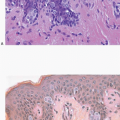

Benign papillomas may undergo infarction, particularly larger central lesions; this may occur spontaneously or may be associated with trauma, such as a needling procedure (fine-needle aspiration or core-needle biopsy). Infarction is frequently associated with entrapment of benign epithelium at the periphery of the lesion. The entrapped epithelium may exhibit reactive cytologic atypia or squamous metaplasia (

Fig. 8.10,

e-Fig. 8.9).

3Although the histologic features of peripheral papillomas are similar to those of central papillomas, the epithelium of the peripheral lesions more often shows foci of ADH and DCIS than that of solitary, central papillomas.

4,

5Intraductal papillomas are benign lesions that are adequately treated by excision. The risk of subsequent breast cancer associated with solitary intraductal papillomas is similar to that of women with other proliferative lesions without atypia (relative risk ∽2 compared with the general population). Multiple papillomas appear to be associated with a higher risk of concurrent and subsequent carcinoma than do solitary, central papillomas.

1,

5,

6 and

7 The key features of intraductal papillomas are summarized in

Table 8.2.