Pap Smears and Abnormal Cervical Cytology

Anna-Barbara Moscicki

KEY WORDS

Cervical cancer screening

Cytology

Human papillomavirus

The prevalence of abnormal cytology peaks in adolescent and young adult (AYA) women in the US, with rates ranging from 3% to 14%.1 This is not surprising since this parallels the peak prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) of around 25% to 41% in the US and European women under 25 years of age.2,3 The high rates of HPV and abnormal cytology underscore the vulnerability of young women to HPV. It is estimated that over 60% of young sexually active women will acquire HPV at least once within 3 to 5 years after the onset of sexual intercourse.4 Repeated infections are also common in young women, with 70% to 80% acquiring second and third infections within 3 years of the initial infection.5 Infection with multiple HPV types is also common. Fortunately, most of these infections and their corresponding abnormal cytologies spontaneously regress.1

The majority of the abnormal cytology is low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs), which are considered benign changes due to HPV infection. These lesions are found to be associated with both low (nononcogenic) and high (oncogenic) risk HPV types.6 High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) are considered true precancer lesions. Although the rates of these are substantially lower than those of LSILs in adolescents and young women, the prevalence of both of these lesions peaks in young adult women less than 30 years of age.1 The prevalence of cytologic LSIL and HSIL among 21- to 24-year-olds is 6.5% and 0.7%, respectively, and among 25- to 29-year-olds is 3.8% and 0.4%.7 Because of the insensitive nature of cytology, the actual rates of histologic HSIL8 are higher. Studies that incorporate colposcopy and biopsy show that the rate of histologic HSIL is higher than cytology. In one large study, the prevalence of histologic HSIL was 1.3% and 2.1% in 21 to 24 and 25- to 29-year-olds, respectively.7 The natural history of HSIL is also influenced by age. HSIL in young women is much more likely to regress spontaneously than in older women. One study of AYA women aged 13 to 24 years of age showed that 70% of biopsy-proven HSIL regressed over 3 years.9 Of those HPV 16/18 associated, 50% regressed. Several other studies of young women showed similar results.10 Although the reasons for this are not completely clear, it is likely that HSIL develops relatively quickly after infection in cells vulnerable to dysplasia. Consequently, HSIL in a young woman likely represents a relatively recent abnormality when the chances of clearance are the greatest. HSIL detected in an older woman is far more likely due to a long-term persistent infection of which the immune system fails to clear.11

The importance of the cervical transformation zone (TZ) in cancer development has long been recognized. It is useful to review the formation of this zone and the natural history of HPV in understanding abnormal cervical changes.12

In Utero and Prepuberty

During embryological development, the müllerian ducts give rise to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina. These structures in the fetus are lined by immature cuboidal epithelium (which becomes columnar epithelium) from the uterus to the hymenal ring. The urogenital sinus epithelium grows up the vaginal vault and replaces the native epithelium up to the ectocervix with squamous epithelium. This replacement is usually incomplete, creating an abrupt squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) on the ectocervix. Squamous metaplasia is a process during which undifferentiated columnar cells transform themselves into squamous epithelium. However, the process is relatively quiescent until puberty, resulting in little changes to the SCJ during childhood. The area of columnar epithelium seen on the ectocervix is referred to as ectopy.

Pubertal Metaplastic Changes

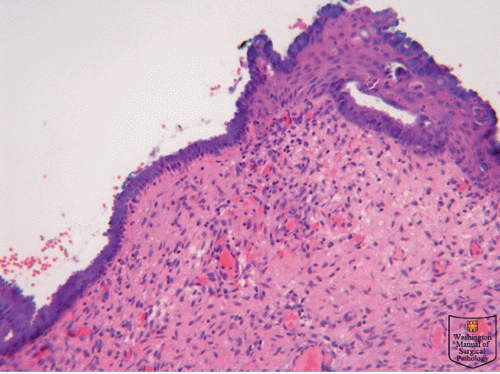

With puberty, the pH level of the vagina drops and this is thought to be secondary to rising levels of estrogen, which enhances glycogen production of the squamous cells, which in turn provides a source of energy for the vaginal flora, specifically lactobacilli. Lactobacilli convert glycogen to lactic acids, resulting in a lowered pH level. This new acidic environment most likely contributes to the augmentation of the squamous metaplastic process, resulting in relatively rapid replacement of columnar epithelium by squamous epithelium, hence referred to as the TZ (Fig. 50.1).

The TZ is a relatively fluid area of definition, because it represents the area between the original SCJ and the current SCJ. By the early 30s, most women have had substantial replacement of their columnar epithelium, resulting in little to no visible ectopy. Although squamous metaplasia continues, it is now found well inside the endocervical canal.

Squamous epithelium is generally 60 to 80 cell layers thick and appears smooth and pink covering the vagina and a portion of the ectocervix. Columnar epithelium is a single-layer, mucus-producing, tall epithelium extending between the endometrium and the squamous epithelium. This thin layer results in a red

appearance due to its increased vascularity and has an irregular surface with long papillae and deep clefts. During puberty, the TZ is a combination of squamous and columnar epithelium as well as metaplastic tissue. Hallmarks of metaplasia seen on magnification include fusion of the villi causing a loss of translucency to the columnar epithelium. Eventually the papillary structures are lost, and the new surface takes on a less translucent appearance more similar to squamous epithelium. As this process is somewhat piecemeal, the examiner can often see reminants of columnar epithelium in small pockets. When these openings become completely closed by squamous epithelium, the mucus-secreting epithelium may continue to produce mucus. If that mucus becomes inspissated, the gland dilates and a nabothian cyst results. Nabothian cysts eventually self-destruct from the pressure of the inspissated mucus.

appearance due to its increased vascularity and has an irregular surface with long papillae and deep clefts. During puberty, the TZ is a combination of squamous and columnar epithelium as well as metaplastic tissue. Hallmarks of metaplasia seen on magnification include fusion of the villi causing a loss of translucency to the columnar epithelium. Eventually the papillary structures are lost, and the new surface takes on a less translucent appearance more similar to squamous epithelium. As this process is somewhat piecemeal, the examiner can often see reminants of columnar epithelium in small pockets. When these openings become completely closed by squamous epithelium, the mucus-secreting epithelium may continue to produce mucus. If that mucus becomes inspissated, the gland dilates and a nabothian cyst results. Nabothian cysts eventually self-destruct from the pressure of the inspissated mucus.

Metaplasia and HPV Infections

The vulnerability of the cervix to HPV infections is most likely related to the process of squamous metaplasia.13 This association reflects the natural life cycle of HPV and its dependence on host cell proliferation and differentiation, both characteristics of squamous metaplasia. Initial HPV infections are thought to occur by invasion of cells of the basal epithelium. Disruption of the epithelium by inflammation or trauma may cause an increased risk for infection with HPV. Differentiation of these basal cells to well-differentiated squamous epithelial cells supports HPV replication by allowing expression of certain viral proteins at different layers of differentiation. The expression of the oncogenic proteins E6 and E7 in turn causes histological changes, which include abnormal cell proliferation, and the appearance of abnormal mitotic figures, both features of SIL. Features that are mild in nature and restricted to the basal and parabasal areas are referred to as LSIL. When these features become more extensive and extend into the upper half of the epithelium, the changes are referred to as HSIL. These changes coincide with increased expression of the oncogenes E6 and E7. Consequently, both LSIL and HSIL are pathological changes due to HPV infection.

Impact of Cofactors

HPV infection is clearly the causative factor for cervical SIL and cancer, and sexual behavior is the strongest risk for HPV infections specifically reporting new sexual partner or having a nonmonogamous relationship.5,14 Acquiring other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) also increases the risk, which may represent a break in the cervical barrier due to inflammation caused by the STI or reflects the “at risk” partner. Condom use also shows some protection against HPV acquisition underscoring important counseling messages to young women.

Causes of cervical cancer are more complex. Because the rates of HPV are 100 to 700 times more common than invasive cancers, it is assumed that HPV is necessary but not sufficient for the development of cancer. Most HPV infections are quickly eliminated by the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses.15,16 Innate responses are likely responsible for rapid clearance, whereas cell-mediated immune responses are important in clearing established infections as well as offering protection from re-exposure. This immune response is likely responsible for the observation that with age the prevalence of HPV declines. In comparison, lack of an adequate immune response results in persistence of HPV infection, and in turn, HPV persistence is a strong risk for the development of HSIL and cervical cancer.11 In a study of young women, HPV 16 persistence at 2 years was associated with a 50% risk of CIN 3 within 12 years.11 HPV persistence is a common problem among persons with immunodeficiencies including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.17

Another factor associated with cancer development is tobacco exposure. Even when adjusted for numbers of sex partners, women who smoke have a higher risk of developing cervical SIL and invasive cancers than nonsmokers.18 Other risk factors implicated include Chlamydia trachomatis infections, multiparity, and history of prolonged oral contraceptive use.1,19,20,21 Final molecular events leading to cancer have not been defined, but include viral integration into the host chromosome and activation of telomerase to lengthen chromosomes and avoid physiologic cell senescence.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree