Pancreatic resection can be performed safely in the community-based hospital setting only when appropriate systems are in place for patient selection and preoperative, operative, and postoperative care. Pancreatic surgery cannot be performed optimally without considerable investment in, and coordination of, multiple departments. Delivery of high-quality pancreatic cancer care demands a rigorous assessment of the hospital structure and the processes through which this care is delivered; however, when a hospital makes the considerable effort to establish the necessary systems required for delivery of quality pancreatic cancer care, the community and hospital will benefit substantially.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States, with more than 43,000 new cases and 36,800 deaths estimated in 2010 alone. The 5-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer remains less than 5%. Because curative systemic treatment modalities for pancreatic cancer have yet to be discovered, pancreatic resection remains the only potentially curative treatment option for the less-unfortunate one of five patients with a resectable lesion. For these patients, a combination of surgical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy can provide a 5-year survival rate of up to 30%.

Delivery of the highest quality surgical care to patients with pancreatic cancer requires considerable dedication of hospital resources, specific expertise, and interdepartmental coordination. Therefore, the appropriate setting for pancreatic surgery has been a topic of intense debate recently. Most current evidence suggests that hospitals with a high annual volume of pancreatic surgeries have improved short- and long-term risk-adjusted outcomes after pancreatic resection for cancer. Experts have proposed that higher volume is likely a definable surrogate marker for higher-quality systems of patient care at these centers.

Given these data, regionalization of pancreatic resections to high-volume centers seems ideal; however, significant obstacles remain, including disparities in access to a high-volume center, prolonged patient travel times, patient preference for local over remote care, and the impact of a referral policy on the referring and receiving hospitals. Despite these limitations, significant steps have been taken in the United States and Europe toward regionalization of pancreatic resection ; nevertheless, most pancreatic resections in the United States are still performed at low- or medium-volume centers.

Most of these high-volume centers are large, academic, tertiary care hospitals, and the low- and medium-volume centers are essentially community hospitals of varying size with or without an academic affiliation. In response to the large volume of literature showing better outcomes at high-volume centers, surgeons at many of these low- to medium-volume community hospitals have published their exceptional outcomes after pancreatic resection. A cohesive argument has been made that volume does not dictate outcome; however, high-volume centers on average operate significantly higher-quality systems of care, and these systems do dictate outcome. Significant efforts have been made to understand the structure and process behind this association, with the hope that these systems can translate into improved patient care at low- and medium-volume centers. Multiple preoperative, operative, and postoperative elements have been recognized as essential to providing the standard of care for patients with pancreatic cancer. All centers, regardless of volume, must implement these elements and track their outcomes to ensure they are meeting the standard.

This article discusses the implementation of these key elements of pancreatic cancer care during the development of a successful pancreatic surgery program at a large tertiary care community hospital. Carolinas Medical Center (CMC) has rapidly transitioned from a low- to a high-volume center for pancreatic cancer surgery since the inception of the hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgery program in October 2006. This rapid emergence of a high-volume pancreatic care center in an area where patients may not have been referred for surgery previously, had their surgery at low-volume community hospitals in the area, or were referred elsewhere for surgery has had a substantial effect on pancreatic cancer care in the surrounding community and central and western North Carolina.

Changing demographics after the introduction of a new regional HPB referral center

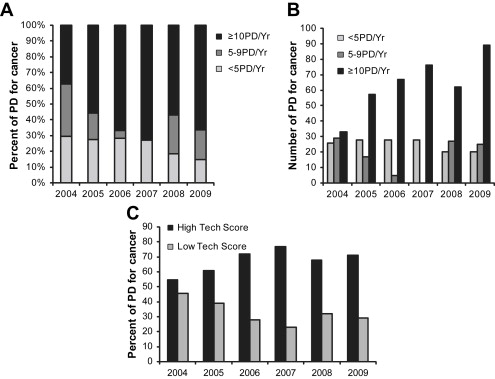

The CMC HPB program was initiated in late 2006 to respond to a need for specialized HPB surgery in central and western North Carolina. CMC, a large tertiary care community teaching hospital, subsequently transitioned from a low- to a high-volume center in late 2006. To investigate the impact of this new referral center, the North Carolina Hospital Discharge Database (Thomson Reuters, Fiscal Years 2004–2009) was queried for all patients undergoing resection for pancreatic cancer from 2004 to 2009. Hospitals were then divided into volume categories based upon the total number of pancreaticoduodenectomy operations performed for cancer per year, with low-volume consisting of <5 PD/year, mid- volume consisting of 5–9 PD/year, and high-volume consisting of 10 or more PD/year. The annual distribution of cases to low-, mid-, and high-volume centers over this time span reflects a consistent trend toward regionalization to high-volume centers in North Carolina ( Fig. 1 A, B) and toward large centers that have more resources available, such as the ability to support solid organ transplant and open heart surgery programs ( Fig. 1 C). The designation of academic or community hospital is less important than possessing the appropriate resources to perform complex operations such as pancreatic resection.

These data suggest an increase in regionalization to centers that specialize in pancreatic cancer care in North Carolina since 2004. A concomitant push toward regionalization has undoubtedly occurred nationwide, and these statewide data likely reflect this trend; however, these data also support the idea that being properly equipped to deliver high-quality pancreatic cancer care is the most important factor in determining referral patterns. The CMC HPB program was instituted in the middle of this timeframe, and has undoubtedly contributed to this increase in regionalization.

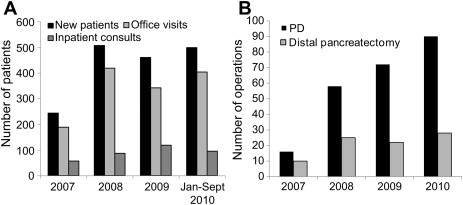

Growth of the CMC HPB program since October 2006 has been exponential. New patient office visits and consultations for all HPB diseases have increased from 244 in 2007 to 460 in 2009, an increase of 189% ( Fig. 2 A). Case-specific volume has also increased, with 16 PDs performed in 2007 for all causes, and 72 performed for all causes in 2009, an increase of 450% ( Fig. 2 B).

Key components of a pancreatic cancer care program

Multiple components are essential for the delivery of high-quality pancreatic cancer care, regardless of the hospital setting in which it is delivered. This article describes these components and their integration into the CMC program as it was developed.

Essential Hospital Components

Hospital location is a key component required to support a pancreatic cancer care program. In short, a significant need must exist in the community, and the hospital must establish a strong referral network throughout the community. In a recent analysis of all patients with potentially resectable stage I pancreatic cancer in the National Cancer Database from 1995 to 2004, only 28.6% underwent surgery. Of the remaining 71.4%, a disturbingly high percentage (38.2%) were never offered surgery, and another 13.5% had no recorded reason for not undergoing surgery. This underuse of the only curative option for patients with stage I pancreatic cancer suggests a pessimistic view of the outcomes of pancreatic resection and the survival of pancreatic cancer patients in general.

A major service to the community is simply spreading the word to the treating physicians in the region that a safe and effective pancreatic surgery option is available to their patients with pancreatic cancer. Equally important is the need to update physicians outside the oncologic community regarding the quickly evolving treatment algorithms for pancreatic cancer. For example, the cancer that was considered unresectable in the past may be amenable to neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by resection today, and the dreaded CT scan showing portal vein involvement is no longer an absolute contraindication to resection. Given these advances, even experienced surgeons in centers capable of supporting routine pancreatic resection should, when treating high-risk patients with difficult anatomy, consider referral for a second opinion rather than deeming these patients inoperable. Establishing a strong referral and education network in the community is key to maximizing the use of surgical resection in patients who deserve that option.

The CMC HPB program was established in a region where patients were either not being referred for pancreatic resection, being referred and deemed unresectable, or being referred elsewhere for pancreatic resection. The Carolinas Healthcare System includes more than 30 hospitals in North and South Carolina, thus facilitating the process of implementing a referral mechanism within the system.

The ability of the staff at a hospital to recognize and respond appropriately to a postoperative complication is a key aspect of patient care after pancreatic resection. In reviewing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for pancreatic resections from 2000 to 2006, five hospital characteristics known to be associated with improved outcomes were tested for an effect on “failure to rescue,” defined as inability to prevent death after a major complication. These variables included teaching status, size greater than 200 beds, average census more than 50% full, increased nurse-to-patient ratio, and high hospital technology scores (defined as the ability to support an open heart and solid organ transplant service). All of the variables tested were associated with improved ability to prevent death from a major postoperative complication, supporting the idea that certain elements of hospital structure and process are essential to ensuring excellent outcomes after pancreatic surgery. CMC is a 1000-bed tertiary care teaching hospital that supports busy cardiac surgery and solid organ transplant programs, and has a general surgery residency program and multiple surgical fellowships.

Essential Components of an HPB Service

One of the major contributors to the improved outcomes seen at high-volume hospitals for select technically complex operations is the individual surgeon volume at these high-volume hospitals, which appears to be particularly important for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Birkmeyer and colleagues analyzed the Medical Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) files for all Medicare patients undergoing 1 of 14 major cardiovascular or cancer operations in 1998 and 1999. For pancreatic resection for cancer, they showed that 54% of the decrease in hospital mortality seen at high-volume centers could be attributed to surgeon volume. Similarly, in a risk-adjusted analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample for all pancreatic resections performed from 1998 to 2005, in which surgeon and hospital identifiers were recorded, high-volume surgeons were associated with an even lower risk of mortality than high-volume hospitals. Inpatient mortality after pancreatic resection seems to be the most surgeon-dependent compared with other complex hepatobiliary operations. This finding is reflected in an analysis of the State Inpatient Databases for three states that record both hospital- and surgeon-specific data. In this analysis, high-volume centers had lower mortality than low-volume centers for all complex HPB operations; however, for PD this difference was largely attributable to high-volume surgeons, pointing toward the high operative expertise required for this specific procedure.

Because a notable learning curve exists for performance of pancreatic resections, surgeons who perform pancreatic resections must have adequate experience. In a review of outcomes after pancreatic resection at one high-volume cancer center spanning 15 years, a comparison of three surgeons’ first versus second 60 PDs showed that increased experience resulted in lower margin positivity, higher lymph node yield, shorter length of stay, shorter operative times, and less blood loss. Similarly, in an analysis of PDs performed at another high-volume referral center for pancreatic cancer care, surgeons who had performed more than 50 PDs in their career had significantly lower morbidity, shorter operative times, and less blood loss than less experienced surgeons, despite performing significantly more complex vascular resections in conjunction with the PD. For the generation of surgeons emerging from surgical residency today, this means that additional fellowship training is essential to ensure adequate outcomes. The establishment of an HPB program at CMC was predicated on recruiting experienced board-certified fellowship-trained HPB surgeons, and the dedication to this advanced training is evidenced by the establishment of an accredited HPB fellowship program.

Regarding the structure of an HPB service, the authors have found that the establishment of a separate HPB call schedule and service, including an HPB clinical fellow and residents, dedicated mid-level providers, and dedicated operating room and clinical nursing staff, is highly beneficial in the coordination of care for these patients. In caring for a predominantly older population undergoing major pancreatic resection, it is essential to maximize continuity of care and minimize the “hand-offs” and “cross-coverage” that can lead to communication error, particularly in the current era of residency work-hour restrictions.

Essential Components of Nonsurgical Departments

As important as the surgeons and HPB service are, delivery of quality care to patients with pancreatic cancer involves much more than the surgical team. Recruiting and establishing HPB expertise across departments is absolutely essential.

Strong medical and radiation oncology programs should be in place for optimal preoperative and postoperative pancreatic cancer treatment programs. Adjuvant gemcitabine-based chemotherapy is now well-known to improve survival after pancreatic cancer resection and is considered standard of care. The evidence for adjuvant radiation therapy is less well established; however, its use in combination with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting may decrease margin-positive resection and improve survival. This use may be particularly applicable in the “borderline” resectable patient in whom the extent of local disease is formidable. Keeping in mind the fact that 70% to 80% of patients with pancreatic cancer will not be candidates for resection, an experienced and capable medical oncology program must also be in place to offer the best available treatment for these patients. A team approach to pancreatic cancer resection, implementing all three forms of therapy as indicated, is critical to meeting the standard of care for pancreas surgery.

The gastrointestinal medicine department at a pancreatic cancer care center should incorporate expertise in endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Like other ultrasound procedures, performance of EUS is heavily operator-dependent, and requires advanced training beyond a gastrointestinal fellowship and a minimum number of proctored cases to obtain certification. EUS has a reported T-stage accuracy of 78% to 94% and N-stage accuracy of 64% to 82% across several series, and is more sensitive for detecting small tumors (<2 cm in diameter) and suspicious lymph nodes than both CT and MRI. EUS also offers the advantage of allowing guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of pancreatic masses and adjacent lymph nodes, with a reported diagnostic accuracy of 72% for pancreatic cancer. However, in addition to endoscopist expertise, pathologist experience in evaluating cytologic specimens from EUS-guided FNA is required to reach the full diagnostic potential. EUS-guided FNA is more specific (98%) than sensitive (85%), meaning that a negative result does not definitively rule out cancer. Thus, its use is particularly advantageous in patients who have suspicious lymph nodes outside of the resection field or who have a low suspicion of pancreatic cancer, thus decreasing the possibility of performing an unnecessary resection.

Given these advantages in diagnosis and patient selection, the institution of an EUS program is an indispensible part of any pancreatic cancer care program. After the HPB program was established at CMC, an EUS program was started in the fall of 2007. The annual volume has continued to expand, with EUS performed in 1730 patients in 3 years. More than 60% of these patients were being evaluated for HPB-related disease.

Expertise in ERCP also requires advanced training beyond a gastrointestinal fellowship. Expertise in ERCP and common bile duct (CBD) stent placement should be readily available for the preoperative evaluation of many patients with pancreatic cancer and biliary obstruction. Although previously, CBD stents were routinely placed in all of these patients, its indication for biliary obstruction has narrowed recently. A recent review showed that stent-related complications led to a significant delay in resection and an increased postoperative infection rate in patients who underwent preoperative biliary drainage, thus challenging the efficacy of routine preoperative drainage. However, biliary drainage in symptomatic potentially resectable patients, and those with obstruction secondary to unresectable cancer, remains a mainstay in the complete approach to pancreatic cancer care.

The radiology department is an integral part of a pancreatic cancer care program. The resources and expertise to perform and interpret state-of-the-art pancreatic imaging should be available. Pancreatic protocol CT scan, with arterial and delayed portal venous phases, is the authors’ preferred imaging modality for pancreatic tumors, and is highly accurate for detecting tumors as small as 1.5 to 2 cm. Assessment of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), portal vein (PV), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and hepatic artery for vessel invasion, and the liver and lungs for distant metastatic disease, makes pancreatic protocol CT the ideal modality for assessment of resectability. The combination of pancreatic protocol CT and EUS provides the best imaging framework for pancreatic cancer staging. Other imaging modalities, such as MRI, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) have a role to play in select patients, and should be readily available, although they are not currently routinely used.

Even at centers with excellent pancreatic surgeons, complications such as intra-abdominal abscess formation and anastomotic leaks undoubtedly will occur after pancreatic surgery, and therefore these complications must be recognized and managed efficiently. A skilled on-site interventional radiology department is essential to help treat these patients after a complication. Postoperative abscess drainage, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography/biliary drainage, and arterial embolization are common minimally invasive methods that can prevent the morbidity of a second trip to the operating room for these patients.

The anesthesia department plays a very important role in the perioperative care of patients undergoing pancreatic resection. Expertise in managing the intraoperative volume status and regional pain control for these patients is critical. The authors have found that working with a dedicated group of anesthesia staff and Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists familiar with the requirements of an HPB operation is very beneficial. Similarly, a critical care team familiar with management issues of these patients, who are often older and frail, after pancreatic resection is essential to ensure optimal outcomes. Twenty-four-hour intensive care unit staffing by an intensivist is now considered standard of care.

Finally, the pathology department is also important in the team approach to pancreatic cancer resection. Expertise in interpreting and reporting cytology from EUS-guided FNA and surgical resection specimens is essential. The PD specimen should be inked and sectioned to evaluate margins of transection (duodenum, bile duct, pancreatic neck, jejunum), radial retroperitoneal margins, and the margin between the uncinate process and the SMA. This thorough evaluation requires coordination between the pathologist and the surgeon. The authors have found it highly beneficial to personally take the specimen to the pathology laboratory and mark it together with the pathologist. The tumor grade, number of positive lymph nodes, and total number of lymph nodes resected should be routinely reported in a consistent manner.

Performing pancreatic cancer resections in a hospital that is dedicated to broad cancer care offers other benefits that cannot be overlooked. Patients who have undergone pancreatic resection often require specific diet and medication adjustments for issues such as delayed gastric emptying and pancreatic insufficiency. Having a dedicated nutritionist program to help these patients with these difficult transitions is very helpful. Providing patient advocates who can help these patients navigate the complex cancer care network and explain treatment options also benefits patients tremendously.

Coordination of a detailed plan of action for these patients is a difficult task that mandates weekly multidisciplinary conferences incorporating all of the specialties mentioned earlier. The authors have found it beneficial to establish weekly multidisciplinary HPB and gastrointestinal tumor planning conferences, which are video-linked to multiple hospitals within the Carolinas Healthcare System.

Operative Technique

The technique of performing a PD has long been debated, and currently no consensus exists on the superiority of pylorus-preserving versus standard resection or type of pancreaticojejunostomy. Many centers have published excellent results using the technique that they have perfected; however, probably more important than the actual technique is that the surgeon performing the operation be facile and meticulous with the selected method. For example, the surgeons at CMC have found that a pylorus-preserving PD with a duct-to-mucosal anastomosis with the addition of a buttress of vascularized round ligament minimizes the postoperative pancreatic leak rate. Vastly more important than the choice of resection and reconstruction technique is the adherence to and documentation of standard oncologic principles, including thorough evaluation of resectability, skeletonization of the SMA, standard lymphadenectomy, and a coordinated approach with the pathologist for evaluation of margins.

Unfortunately, even when a standard technique is optimized and sound principles of resection are in place, not all pancreatic resections will fit the mold for a routine PD. When offering resection to patients with borderline resectable tumors, the ability to incorporate vascular resection and reconstruction without compounding morbidity is essential. Despite modern imaging, the surgeon often does not know with absolute certainty whether vascular resection will be required before beginning the operation. Occasionally, vascular invasion is not apparent until after the surgeon is committed to resection. If these procedures are beyond the scope of the program at a given center, patients with borderline resectable tumors should be offered referral for evaluation at a center with these capabilities before exploration.

Tracking of Patient Outcomes

With the current focus in the medical community and the general public on the issues of patient safety and surgical outcomes, the hospital and surgeon performing pancreatic surgery must track and record their experience, including multiple preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables ( Box 1 ). Often these data are collected and stored by the surgeon or department in personal or departmental databases, with obvious variation in the breadth of the data points collected. Any concerted effort to track and understand surgical outcomes should be applauded; however, a centralized uniform method for collecting and reporting these data will become essential as the requirements for strict surgical quality control continue to expand.

Preoperative

Medical history

Risk factors and comorbid diseases

Presentation

Emergent/urgent/elective

Tumor markers

CA 19.9

Cross-sectional imaging

Location, size, and character of mass

Vascular involvement

Suspicious nodal disease

Metastatic disease

Endoscopic ultrasound

Location, size, and character of mass

Vascular involvement

Suspicious nodal disease

FNA cytology results

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Presence of a stricture or mass

Brushing cytology results

Stent placement

Clinical Stage

TNM stage by current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) guidelines

Assessment of resectability

Resectable/borderline/locally advanced

Neoadjuvant treatment

Type and duration of treatment

Operative

Operating room

Results of exploration for metastatic disease

Type of resection performed

Method of reconstruction

Vascular resection/reconstruction

Extent of lymphadenectomy

Skeletonization of superior mesenteric artery

Frozen section margin results

Estimated blood loss

Operative time

Pathology

Tumor size, location, and grade

TMN stage by current AJCC guidelines

Number of lymph nodes resected

Treatment effect

Lymphovascular/perineural invasion

Margin status

Postoperative

Morbidity and mortality

Pancreatic fistula rate by International study group of pancreatic fistula definition

Postoperative complication rate and type

30- and 90-day mortality rate

Adjuvant treatment

Type and duration of treatment

Recurrence

Timing and location of recurrence

Survival

2- and 5-year survival

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree