Clinical presentation

Diagnosis

Malignant potential

Location in the pancreas

Localization studies

Insulinoma

Symptoms of hypoglycemia

Whipple’s triad

Hypoglycemia

Fasting glucose <40 mg/dl

Symptomatic relief with glucose

Glucose <45 mg/dl (no sulfonylurea)

Insulin >6 u/ml

C-peptide >300 pm/l

10 %

1/3 in head

1/3 in body

1/3 in tail

Most are intrapancreatic

CT, MRI, US, 111In-pentetreotide imaging

18F-DOPA PET, IOUS

Selective angiography with calcium stimulation and hepatic venous sampling

Gastrinoma

ZES

PUD

GERD

Diarrhea

50 % present with metastases

Fasting gastrin >1,000 pg/ml

Secretin stimulation test: gastrin level ≥200 pg/ml

50–60 %

Gastrinoma triangle

Upper endoscopy, EUS

CT, MRI, SRS

Selective angiography with secretin stimulation and hepatic venous sampling

IOUS, transillumination of duodenum, duodenotomy

VIPomas (Verner-Morrison syndrome, WDHA)

WDHA:

Watery diarrhea

Dehydration

Hypokalemia

Achlorhydria

Most present with metastases

Plasma level of VIP >500 pg/ml (normal <190 pg/ml)

60–80 %

Body and tail

95 % solitary

CT, MRI, SRS, EUS

Glucagonoma

Diabetes

Weight loss

Low albumin

Necrolytic migratory erythema

50 % present with metastases

Plasma level of glucagon > 500pg/ml

75–85 %

Body and tail

CT, MRI, SRS, EUS

Angiography

Somatostatinoma

Cholelithiasis

Steatorrhea

Diabetes

Weight loss

Most present with metastases

Plasma level of somatostatin, generally 1,000-fold higher than reference range

65 %

Ampullary, periampullary region

CT, MRI, SRS, EUS

The clinical manifestation of gastrin-secreting PNETs (gastrinoma, or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) is related to the hypersecretion of gastric acid and includes severe peptic ulcer disease/gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), epigastric pain, and diarrhea. The biochemical diagnosis is highly suspected with a fasting gastrin of tenfold above normal (e.g., >1,000 pg/mL). Secretin stimulation test can help secure the diagnosis of gastrinoma; a gastrin level ≥200 pg/ml following secretin stimulation is diagnostic. Nearly 90 % of gastrinomas can be found in the “gastrinoma triangle” or the “Passaro Triangle” [6], a triangle that is formed by the confluence of the cystic duct and common bile duct superiorly, the second and third portion of the duodenum inferiorly, and the neck and body of the pancreas medially (Fig. 24.1).

Fig. 24.1

Gastrinoma Triangle (Passaro Triangle): A triangle that is formed by the confluence of the cystic duct and common bile duct superiorly, the second and third portion of the duodenum inferiorly, and the neck and body of the pancreas medially (Reprinted from Hernandez-Jover et al. [6]. With permission from Springer Verlag)

PNETs that hypersecrete vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPoma, Verner-Morrison syndrome, WDHA) cause the clinical constellation of symptoms of diarrhea, dehydration, and hypokalemia. Plasma hormone levels of VIP are typically >500 pg/mL (normal is typically <190 pg/ mL).

The clinical manifestation of PNETs that hypersecrete glucagons (glucagonoma) include glucose intolerance/diabetes mellitus, weight loss, and a unique dermatitis (necrolytic migratory erythema) [7]. The supporting biochemical study of a glucagonoma is that plasma levels of glucagons are generally >500 pg/mL.

Lastly, the PNETs that are associated with increased secretion of somatostatin do not consistently produce clinical manifestations, but symptoms may include diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, and weight loss. In addition, PNETs may secrete a variety of other hormones (e.g., pancreatic polypeptide, serotonin, calcitonin, growth-hormone-releasing factor) that may or may not be associated with the clinical manifestations.

Familial Syndromes Associated with PNETs

Three familial syndromes are associated with the development of PNETS: (1) multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1), (2) von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), and (3) von Recklinghausen disease (VRH, also termed neurofibromatosis type 1 or NF1). MEN1 is an autosomal dominant syndrome associated with mutation of the MEN1 gene which encodes the menin protein that regulates transcription of a variety of genes involved in cell growth and cell cycle progression. In addition to PNETs, MEN1 is associated with pituitary adenomas (typically prolactin secreting) and hyperparathyroidism (typically four-gland hyperplasia). The PNET most commonly associated with MEN1 is a gastrinoma, though to a lesser degree, insulinomas and glucagonomas are seen; although rare, VIPomas and somatostatinomas can also be associated with MEN 1 syndrome. The hallmark of PNETs associated with MEN1 is the multicentric nature of the tumors distributed throughout the pancreatic gland. A more in-depth discussion of MEN 1 is found in Chap. 25, Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia (MEN) Syndromes.

VHL is an autosomal dominant syndrome associated with mutation of the VHL gene, which encodes for a protein regulating transcription of proteins involved in angiogenesis. VHL is characterized by hemangioblastomas of the eye or cerebral nervous system, renal cell carcinomas, and pheochromocytomas. The PNETs associated with VHL are typically nonfunctional and present in less than 20 % of VHL patients.

VRH is due to mutations in the NF-1 gene which encodes the neurofibromin protein; through binding to microtubules, neurofibromin affects the cellular cytoskeleton. VRH is a relatively common familial syndrome with cutaneous manifestations of café-au-lait spots, neurofibromas, and a variety of cognitive developmental disorders. PNETs are relatively uncommon for VRH patients, though the prototypic tumor is duodenal somatostatinoma.

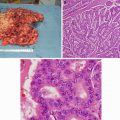

Classification/Staging

The World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 classification of PNETs divides tumors into well differentiated and poorly differentiated based on histopathologic grading (mitotic rate and proliferative index as measured by Ki-67 staining). This grading system is useful in determining overall prognosis (Table 24.2). Both the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society and the American Joint Commission on Cancer have proposed a TNM staging system to predict overall prognosis. These systems incorporate presence of the tumor size (T stage), metastasis to regional lymph nodes (N stage), and absence or presence of distant metastasis (M stage) [8] (Table 24.3).

Table 24.2

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: WHO classification

WHOa classification | Grade | Ki-67 Proliferation rate | Mitotic count per 10 HPF |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | G1 | ≤2 % | <2 |

2 | G2 | 3–20 % | 2–20 |

3 | G3 | >20 % | >20 |

Table 24.3

TNM System of staging for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors

Primary tumor size (cm) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

T1 | ≤2, limited to pancreas |

T2 | >2, limited to pancreas |

T3 | Beyond pancreas, but without involvement of the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery |

T4 | Tumor involves the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery (unresectable primary tumor) |

Regional lymph nodes | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastases | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Staging | |

|---|---|

Stage 0 | TisN0 M0 |

Stage IA | T1N0 M0 |

Stage lB | T2N0 M0 |

Stage IIA | T3N0 M0 |

Stage IIB | T1-3 N1 |

Stage III | T4, Any N, M0 |

Stage IV | Any T, any N, M1 |

The liver represents the most common site of distant metastatic disease. Additional adverse prognostic factors (beyond the WHO histologic classification system) include younger age, male gender, and perhaps extent of extrapancreatic disease.

Radiologic Evaluation of Resectable vs. Unresectable Disease

In a patient with suspected PNET, the most important question to answer is whether the disease is resectable as curative resection remains the cornerstone of treatment in nonmetastatic PNETs. Management of PNETs should be based upon a multidisciplinary approach with the surgeon determining resectability. This decision incorporates the ability to achieve a complete resection of disease which is termed an R0 resection. Patients who present with symptomatic hypersecreting tumors may be palliated if an optimal cytoreductive (>85 %) resection can be achieved. It should be stressed that an optimal cytoreduction procedure should not be considered in an asymptomatic patient. A generalized approach to managing PNETs is shown in Fig. 24.2.

Fig. 24.2

Approaches to PNET therapy. Tabular list of options for therapy to address both symptoms arising from hormonal hypersecretion or surgical management directed at tumor resection

The resectability of the tumor depends on the location and extent of the primary disease as well as whether there is any radiologic evidence of metastatic lesions. There are a number of radiographic tools that can be employed to help the surgeon including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), selective angiography, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). SRS is useful for localizing all of PNETs except for insulinomas; SRS may miss up to 40 % of insulinomas because these tumors lack sufficient amount of subtype 2 somatostatin receptors [9].

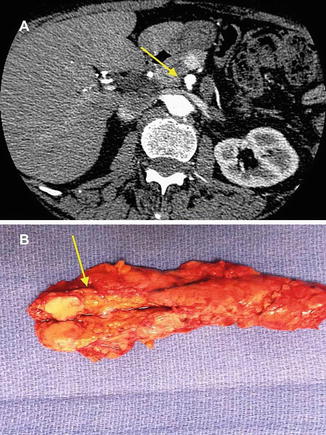

Due to its wide availability and high sensitivity (approaching 90 %), contrast-enhanced triple-phase multidetector CT of the abdomen is the most common and useful imaging modality [10] (see Fig. 24.3). CT has decreased sensitivity for identifying lesions <0.5 cm and if clinical suspicion persists based either on patient symptoms or biochemical evaluation, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) shows great sensitivity for the identification of PNETs less than 0.5 cm in size, particularly in the head of the pancreas. For radiologically occult functional PNETs, additional selective angiography with provocative testing (secretin for gastrinomas and calcium gluconate for insulinomas) and venous sampling may be helpful for localization of small tumors, but high-resolution radiographic imaging and intraoperative ultrasound have decreased the use of this technique.