Injury-related and inflammation-related cysts (30%)

•

Pseudocyst

•

Paraduodenal wall cyst

•

Infection-related cysts

Neoplastic cysts (60%)

Ductal lineage

Mucinous type (30%)

•

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

•

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

•

Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm

•

“Retention cyst”, “mucocele” and “mucinous non-neoplastic cyst”

•

Cystic change in ordinary ductal adenocarcinoma

•

Other invasive carcinomas

Serous (clear-cell) type (20%)

•

Serous cystadenoma

•

Oligocystic (macrocystic) variant of serous cystadenoma

•

von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and associated pancreatic cysts

•

Serous cystadenocarcinoma

Not otherwise specified

•

Intraductal tubular carcinoma

Endocrine lineage (< 5%)

•

Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasm

Acinar lineage (< 1%)

•

Acinar cell cystadenoma (cystic acinar transformation)

•

Acinar cell cystadenocarcinoma

•

Cystic/intraductal acinar cell carcinoma

Endothelial lineage (< 1%)

•

Lymphangioma

Mesenchymal lineage (• 1%)

Undetermined lineage (5%)

•

Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm

Other

•

Mature cystic teratoma

Congenital cysts (< 1%)

•

Duplication (enterogenous) cysts

•

Duodenal diverticula

•

Others

Miscellaneous cysts (< 5%)

•

Lymphoepithelial cyst

•

Squamoid cyst of pancreatic ducts

•

Epidermoid cysts within intrapancreatic accessory spleen

•

Cystic hamartoma

•

Endometriosic cysts

•

Secondary tumors

Serous Cystic Neoplasms

SCAs arise from the centracinar cell/intercalated duct system. They are more frequent in females than males (2:1) and present at a mean age of 75 years. SCAs usually present as large masses measuring up to 25 cm, with 50% located within the head of the pancreas. They are usually single, but multifocal lesions may be associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease [7]. Most patients present with abdominal fullness, vomiting, dyspepsia, weight loss and other vague symptoms [1, 8]; jaundice may be observed; 30% of cases are asymptomatic.

Macroscopically, their surface shows numerous small, thin-walled cysts (spongelike or honeycomb appearance) arranged around a central stellate scar (present in 13–18%) caused by calcification of fibrous stroma (Fig. 7.1). There is no communication with the Wirsung duct. Microscopically, they have a single layer of cuboidal or flattened cells lining small cysts [2]. SCAs express cytokeratins (AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, CK7, CK8, CK18,CK19) and α-inhibin without immunoreactivity to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). The rare oligocystic (macrocystic) variant is composed of larger loculi without a central scar and sometimes making the differential diagnoses with mucinous tumors and pseudocysts is difficult [2].

Fig. 7.1

Microcystic serous adenoma in the body of the pancreas. The cut surface shows numerous small, thin-walled cysts arranged around a central stellate scar

In 90% of patients, it is possible to make the correct diagnosis with clinical and imaging findings. Ultrasound is usually the first step in diagnostic imaging for suspect SCAs, but there are two reasons why the microcystic pattern may not be recognized: (i) in spongelike masses, the multiplicity of the small cysts and the fibrous stroma appears as a solid tumor and (ii) in cases of mixed tumors, the macrocystic component conceals the microcystic component, resulting in a macrocystic mass [9].

Unenhanced CT shows from a poorly defined to a thin, well-defined capsule. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates enhancement of septa and welldelineated small cysts in honeycomb patterns with central scars and capsulae enhancement [10]. Sometimes, the distal pancreas may be atrophic and the common bile duct dilated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a honeycomb shape with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high intensity on T2-weighted images. It is possible to see small cysts and septa as high signal, grape-like clusters on T2-weighted images. Unlike CT, central calcification is rarely visualized with MRI [1]. EUS may help in the diagnosis if the cysts are unilocular and similar to mucinous neoplasms. The analysis of aspirated fluid demonstrates the absence of mucin.

Therapy

The management of asymptomatic pancreatic SCAs is observation with serial follow-up using axial imaging studies. The median growth rate for this neoplasm is 0.6 cm/year, whereas it is significantly greater in large (>4 cm) SCAs, which are more likely to be symptomatic. Therefore, expectant management is reasonable in small asymptomatic tumors. Resection is recommended for large SCAs regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms [11].

MCNs

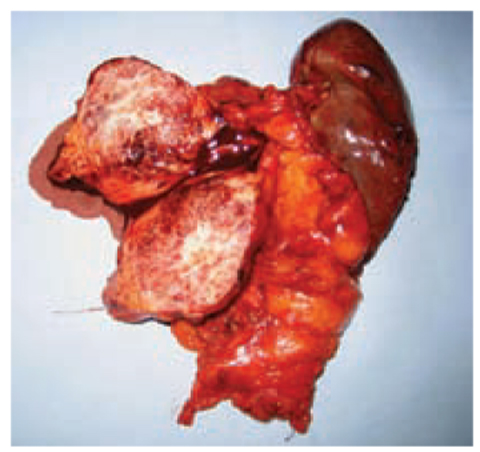

MCNs can be present in perimenopausal females (male:female ratio, 1:20) The mean age of presentation is 48 years. They are more frequently located in the body and tail of the pancreas (70–90%) and are usually large (7–10 cm). They are usually composed by several cysts >2 cm in diameter but also by a single macrocystic lesion [12] (Fig. 7.2). Epigastric pain and abdominal fullness are more frequent symptoms associated with vague symptomatology (anorexia, weight loss, nausea and vomiting). Jaundice may be present if MCNs are in the head of the pancreas.

Fig. 7.2

Mucinous cystoadenoma of the pancreas of a 60-year-old female patient. Macroscopic appearance after distal spleno-pancreatectomy

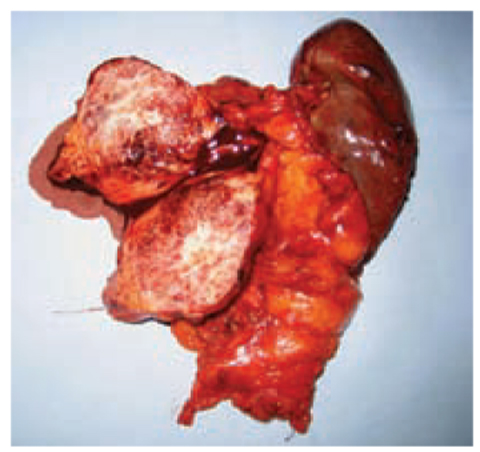

These cystic neoplasms present as thick pseudocapsules and focal calcification at the periphery. In the wall there is primarily a large mass, solid mural nodules, and “velvety” papillation (Fig. 7.3). The cyst contains watery and mucoid fluid. Microscopically, a tall, columnar mucin-producing epithelium is demonstrated that is positive for cytokeratins (CK7, CK8, CK18, CK19), CEA and mucin5AC (MUC5AC). Sometimes there is positivity to neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin [2]. A quasi-requirement for the diagnosis is densely packed spindle cells with sparse cytoplasm and uniform, elongated nuclei (ovarian stroma). MCNs regularly express progesterone receptors and, to lesser degree, estrogen receptors. Cells in the stroma stain for α-inhibin an calretinin.

Fig. 7.3

Mucinous cystoadenoma of the pancreas (cut surface). Velvety papillations are present in the cyst wall

CT shows a large mass with “near water” density, as well as enhancement of septa and the peripheral wall. Typical calcifications (i.e. “eggshell” calcifications) in the peripheral wall and septa may indicate malignancy, in 95% of patients [6]. Also, mural nodules and papillary excrescences are predictive of cystoadenocarcinoma. In these cases, local invasion by obliteration of fat planes and the margins of adjacent organs may be demonstrated [1]. T1- weighted MRI may demonstrate hypodense signal intensity in case of fluid content, whereas protein-based or hemorrhagic liquids appears with hyperdense signal intensity.

Septa and mural nodules may be seen with T2-weighted images. On EUS, mucinous neoplasms are revealed as complex cysts, and are visible septal mural nodules, calcifications and other signs of local invasion, vascular invasion, and lymph-node masses.

Therapy

The therapy of MCNs is surgical excision. This treatment may be influenced by patient age, surgical risk, as well as the histological features, size and location of the tumor.

Distal Pancreatic Resection

The localization of mucinous cystic adenomas is often in the pancreatic body or tail, so distal pancreatectomy is the procedure of choice. It is a safe procedure in high-volume centers (morbidity ranges from 5% to 50% and the mortality rate is 0%) and its main complication, pancreatic fistulas, occurs in 15–20% of cases. MCNs affecting the pancreatic neck or proximal body could require an extended right or, more frequently, an extended left pancreatectomy. These extended resections of normal pancreatic tissue may induce endocrine and exocrine insufficiency in 30–35% and 15–20%, respectively, which in a benign or premalignant disease could be important.

Distal pancreatectomy can be undertaken with splenectomy or in a spleenpreserving fashion. Studies comparing patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy show no significant differences in relation to perioperative complications, mean operation time, pancreatic fistula rate, duration of hospital stay, and mortality. However, to carry out complete oncological lymphadenectomy, spleen-preserving methods must be avoided in the presence of large tumors or risk factors for invasive malignancy, such as the size of the lesion, eggshell calcifications and mural nodules.

Spleen preservation can be undertaken with or without preservation of the splenic artery and vein [13]. Although the procedure without preservation of the splenic artery and vein appears to be technically less difficult and can be achieved in a shorter operating time, it has been associated with a higher incidence of vascular insufficiency in the spleen.

Central Pancreatectomy

MCNs located at the proximal body or neck of the pancreas are suitable for central pancreatectomy. Although the procedure is associated with low mortality, the overall morbidity ranges from 25% to 35%, and the overall prevalence of pancreatic fistulas is 22–45%. This method preserves the spleen and, compared with extended left pancreatectomy or pancreatico-duodenectomy, also preserves endocrine and exocrine functions [14]. Indeed, the prevalence of endocrine and exocrine insufficiency after central pancreatectomy has been reported to be 4–7% and 5–8%, respectively. This surgical method is technically demanding, and associated with a higher prevalence of postoperative complications as well as with the risk of recurrence from potentially residual neoplasms.

Tumor Enucleation

Tumor enucleation has been proposed for patients with MCNs <2 cm (which carry a very low probability of malignancy). The benign features and superficial localization of these tumors direct the choice of surgical strategy. Enucleation avoids postoperative pancreatic insufficiency and can be done without the risk of recurrence. However, it has been associated with a higher prevalence of pancreatic fistulas (30–50%) [15].

Whipple Procedure

A major oncologic resection such as pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without pylorus-preserving surgery is recommended for MCNs localized in the head of the pancreas. Surgical mortality ranges from 0% to 5%, and is generally related to complications due to the pancreatic anastomosis. However, the most common postoperative complications are delayed gastric emptying and pancreatic fistulas, which occur in 5–10% and 6–20% of cases, respectively. When an enucleation is not possible or contraindicated, MCNs localized in the pancreatic head can be treated by a duodenum-preserving total pancreatic head resection (DPPHR). This procedure shows significant advantages when compared with pancreaticoduodenectomy in relation to postoperative rate of morbidity and mortality, glucose metabolism, hospitalization and cost.

Lymphadenectomy

Pancreatectomy with lymph-node dissection must be carried out whenever suspicion of malignancy exists. There is no evidence of invasive mucinous cystic adenocarcinoma with distant lymph-node metastases, so only locoregional lymphadenectomy is justified. In addition, the probability of malignancy is very low in cases of small MCNs without nodules, so lymphadenectomy can be avoided in these cases.

Laparoscopy

In patients with benign-appearing and small malignant lesions (<5 cm), a minimally invasive method must be considered. In general, the laparoscopic approach decreases the duration of hospital stay and minimizes the cosmetic impact of the surgical wound. Recent experiences from high-volume centers have demonstrated that laparoscopic left pancreatectomy for MCNs of the body and tail of the pancreas is feasible and safe. The complication rate of laparoscopic left pancreatectomy ranges between 15% and 20% with a mortality rate of 0% whereas, in spleen-preserving laparoscopic pancreatic resection, the overall morbidity ranges from 25% to 40%. The overall prevalence of pancreatic fistulas was 5–8% and 10–15% after laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy and laparoscopic left pancreatectomy, respectively [16].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree