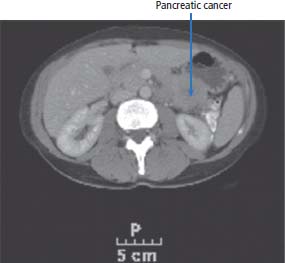

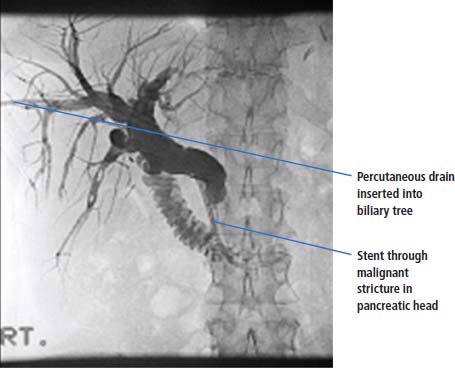

10 The list of celebrities who have died from cancer of the pancreas is lengthy, from the Dirty Dancing actor Patrick Swayze to the Apple founder Steve Jobs; amongst the casualties is Roger (Syd) Barrett the former singer and founder of the psychedelic progressive rock band Pink Floyd. Syd left the band in 1968 after 3 years and became a troubled recluse in Cambridge bothered by the paparazzi. In 1975 his former band mates released the album “Wish you were here” including the tribute track “Shine on you crazy diamond”. We recommend that all students listen to a version of this song on YouTube. Cancer of the pancreas is the tenth most common cancer, and is now the fifth most frequent cause of cancer deaths. There is an equal incidence between the sexes. In 2011, there were 8733 new diagnoses and 8320 deaths attributed to cancer of the pancreas. It is very sad to note that registration figures virtually equal mortality rates. The 5-year survival is just 3% (Table 10.1). Family history contributes to 5–10% pancreatic cancers and includes familial cancer predisposition syndromes as well as hereditary chronic pancreatitis (Table 10.2). In addition to genetic predisposition, environmental causes have been associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Smoking increases the risk 1.5–3-fold; similarly, obesity and lack of physical exercise are risk factors. Chronic pancreatitis increases the risk three times and diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) doubles the risk. Well over 90% of all pancreatic malignancies are exocrine adenocarcinomas, usually arising from ductal cells (85%) but cancers arising from acinar cells and stem cells are also included. You may recall that exocrine glands secrete their products into a duct whilst endocrine glands secrete directly into the bloodstream. Pancreatic exocrine cancers develop from ductal epithelial cells through a sequence of epithelial premalignant lesions known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, with the sequential accumulation of somatic mutations in genes including the oncogene K-RAS and the tumour suppressor genes: P53, P16/CDKN2A and SMAD4/DPC4. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells express a wide variety of receptors that are potential therapeutic targets including epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptors. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma also expresses a wide variety of hormone receptors and these include receptors for so- matostatin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, steroid hormones, IGFs and VEGFs. It should be emphasized that these receptors are present in exocrine pancreatic cancers but are rarely present in the uncommon secretory endocrine pancreatic tumours. The rare endocrine tumours of the pancreas are known as islet cell tumours or nesidioblastomas and include gastrinomas, insulinomas and pancreatic carcinoids. These tumours may be functional or non-secretory. Table 10.1 UK registrations for pancreatic cancer 2010 Patients with cancer of the pancreas present with many different symptoms. These include abdominal and back pain, weight loss, anorexia and fatigue. In many patients the disease is asymptomatic, until they present with obstructive jaundice. Other, less common presentations include superficial venous thrombosis (Trousseau’s sign), a palpable gallbladder in the presence of obstructive jaundice (Courvoisier’s law states that this combination is unlikely to be due to gall stones) and diabetes. Because of the anatomical position of the tumour, late presentation is very common. The patient with a suspected diagnosis of pancreatic cancer should be referred by his or her GP to a general surgeon or a gastroenterologist and be seen in outpatients within 2 weeks of receipt of the GP’s letter of referral. The clinician should organize a number of tests, which include full blood count, renal and liver function tests, a chest X-ray and a CT scan of the abdomen (Figure 10.1). Abdominal ultrasonography is also helpful but endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is probably the most valuable diagnostic test when coupled with percutaneous needle biopsy. The measurement of serum levels of the carbohydrate antigen tumour marker CA19-9 is less helpful in the diagnosis of cancer of the pancreas as it may be elevated in most causes of obstructive jaundice (false positive) and may be normal in patients with pancreatic cancer (false negative). CA19-9 is, however, useful in monitoring cancer of the pancreas in patients with raised levels at diagnosis. Table 10.2 Familial cancer predisposition syndromes that increase the risk of pancreatic cancer Figure 10.1 CT scan of a mass in the tail and body of the pancreas showing a low attenuation centre, suggesting central necrosis of an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Investigation of the patient with pancreatic cancer is aimed at establishing the diagnosis and defining operability. After the initial tests have been carried out, the patient should proceed to EUS or, if not available, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). At ERCP, cytology specimens may be obtained from brushings, suction of the pancreatic duct or biopsy. ERCP is more invasive than other diagnostic imaging modalities and carries a significant complication rate so it is usually reserved for patients with biliary obstruction who require stenting. A failure to obtain a diagnosis by endoscopy should be followed by further investigation. Fine needle aspiration cytology under CT scan is usually successful at obtaining a tissue diagnosis. As with other cancers, numerous different staging systems are used including the TNM classification. The group staging system is summarized below: The vast majority of pancreatic cancers are exocrine adenocarcinomas of ductal origin and they are graded as either well, moderately or poorly differentiated tumours. The tiny minority of endocrine tumours are classified according to the products that they secrete. There is considerable nihilism attached, quite reasonably, to the treatment of a patient with pancreatic cancer. The initial management consists of relieving symptoms of pain and obstructive jaundice. For less than 20% of patients is there any hope for operability, as defined by imaging. No attempt should be made to proceed to surgery until jaundice has completely resolved. Jaundice is dealt with by relief of biliary obstruction, either by endoscopic stenting or by percutaneous transhepatic stenting of the biliary system (Figure 10.2). Pain may be relieved by the use of opiates or may resolve with the relief of biliary obstruction. At laparotomy, only a third of the 20% of patients with radiologically operable disease turn out to have surgically operable tumours. Pancreatic surgery requires a considerable degree of specialization and should not be carried out outside of the setting of a specialist treatment centre. The reason for this is simple: specialist centres achieve better survival rates and lower morbidity and mortality rates. The operation of choice is Whipple’s procedure, and this involves removal of the distal half of the stomach (antrectomy), gallbladder (cholecystectomy), distal common bile duct (choledochectomy), head of the pancreas, duodenum and proximal jejunum (pancreatoduodenectomy), and regional lymph nodes. Reconstruction consists of attaching the pancreas to the jejunum (pancreaticojejunostomy), the common bile duct to the jejunum (choledochojejunostomy), and the stomach to the jejunum (gastrojejunostomy), to allow bile, digestive juices and food to flow! There are modifications of this procedure, such as the pylorus-conserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, that are associated with less postoperative morbidity and equivalent efficacy. Thirty years ago, surgery for pancreatic cancer was associated with a very high morbidity of approximately 25%. This has fallen in specialist centres to 5%, with the expectation that 20% of patients with operable disease will survive 5 years. Post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid, or gemcitabine modestly improves survival. Trials of chemoradiation, as an adjunct to surgery, marginally improve survival but at a cost of considerable toxicity. Ampullary carcinomas of the pancreas generally present with early-stage disease because of their anatomical position. These tumours are associated with better prognoses than cancers of the rest of the pancreas. Patients with inoperable pancreatic cancer have a poor prognosis and the treatment of this condition is palliative. The median survival is 4–6 months. Active treatment with chemotherapy may be advised. The most successful chemotherapy programmes have response rates of up to 40%, but the median duration of survival of these responding patients is just 1 month longer than might be expected without active treatment. Because pancreatic cancer is relatively common, a number of chemotherapy agents have been tried for this condition. Combination therapy using the more toxic agents, such as anthracyclines and taxanes, offers little benefit. The current consensus view is that gemcitabine with either capecitabine or carboplatin or cisplatin probably offers as good an opportunity for disease palliation as any other combination. Quality-of-life issues are paramount in this condition because of the poor prognosis for inoperable disease. Figure 10.2 Two stents: bilirary obstruction due to malignant stricture in head of pancreas. The expression by pancreatic exocrine cancer cells of numerous receptors and the poor results with systemic chemotherapy have led to strategies targeting these receptors. EGF receptor inhibitors including the protein kinase inhibitor erlotinib and the monoclonal antibody cetuximab have been studied with limited success. The VEGF pathway has also been targeted with the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors of VEGF receptors including sorafenib. Again the results are disappointing. The IGF pathway that is activated in pancreatic and other cancers is a novel target for therapeutic strategies and monoclonal antibodies targeting both the ligand (IGF1 and IGF2) and the receptor (IGF receptor 1, IGFR1) are under investigation along with receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors of IGFR1. The transfer of suicide genes to tumour cells by retroviral vectors has also been applied in pancreatic cancer cell lines. This approach is known as gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (GDEPT). The adenovirus vector that was used carried the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene that phosphorylates the prodrug ganciclovir into deoxyGTP that is incorporated into replicating DNA, causing strand termination. This GDEPT strategy inhibited gene expression and cell growth of pancreatic cancer cell lines. This strategy is being investigated in clinical trials. An alternative approach to the management of pancreatic cancer is to focus only on treating the symptoms: stenting to relieve jaundice and coeliac axis nerve block to relieve pain. This procedure blocks the pain fibres originating from the pancreas and ensures good quality of life. The technique requires skill and is relatively well tolerated. The outlook even for patients with operable pancreatic cancer is unfortunately not particularly good, with a 20% chance of 5-year survival. The outlook for those patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease is very poor, with a median survival of 3–4 months. It is for this reason that there is such an emphasis upon quality of life in pancreatic cancer, rather than on the prospects for cure. Table 10.3 Clinical manifestations of secretory endocrine tumours MEN, multiple endocrine neoplasia; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; VIP, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. This is a fascinating group of tumours, interesting not only because of their biology, but also because patients with these tumours are expected to do well. Pancreatic endocrine tumours include tumours arising from islet cells (insulinomas, glucagonomas, gastrinomas and VIPomas) and neuroendocrine tumours originating from enterochromaffin cells (carcinoids). The bizarre constellation of symptoms produced by carcinoids are interesting even to medical students, as are the gastrointestinal symptoms resulting from gastrinomas and VIPomas, and the hypo- and hyperglycaemia from insulinomas and glucagonomas, respectively (Table 10.3). Old school general physicians will expect every medical student reading this book to be able to recount the umpteen skin conditions associated with carcinoid tumours, as well as describe the reasons for the effects of this tumour on the heart. They will take delight in quizzing you on their ward rounds, so we suggest that you google these symptoms and signs if there is an inpatient with carcinoid on your ward. These endocrine malignancies can be associated with enormously long natural histories, which may date back over decades. The major treatment options for pancreatic endocrine tumours include octreotide to decrease hormonal secretion, and chemoembolization to reduce the symptoms that result from tumour bulk. Octreotide is an octapeptide mimic of somatostatin that inhibits the secretion of a whole host of peptide hormones including gastrin, glucagon, growth hormone, insulin, pancreatic polypeptide (PP) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP). Octreotide also reduces pancreatic and intestinal fluid secretion, hence it is used in the management of malignant bowel obstruction. Octreotide has a median period of effect of 1 year in carcinoids, but leads to no clinical evidence of disease regression. Interferon may also lead to a reduction in secretory symptoms of carcinoid tumours. Where symptoms are significant and octreotide has failed, embolization is considered, both to the primary site and to hepatic metastases. Embolization is a significant enterprise and is associated with mortality rates of 3–5% in even the best centres. It should therefore be considered with great care before it is undertaken. The mTOR inhibitor everolimus and sunitinib both have been found to have activity in neuroendocrine pancreatic cancers. Everolimus used in combination with octreotide should be considered the current treatment standard, near trebling progression free survival in a “landmark” clinical trial. The authors of Lecture Notes like landmarks. Case Study: Once a surgeon, always a surgeon.

Pancreatic cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Pancreatic cancer

3.8

3.6

8th

12th

1 in 74

1 in 73

+7%

+0%

3.8%

3.6%

Presentation

Syndrome

Gene affected

Lifetime risk of cancer of pancreas

Hereditary pancreatitis

PRSS1

25–40%

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

STK11

11–36%

Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMM)

CDKN2A

10–19%

Hereditary breast ovary cancer syndrome

BRCA-2

3–5%

Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer)

DNA mismatch repair genes

4%

Staging and grading

Treatment

Treatment of inoperable disease

Prognosis

Tumour

Major feature

Minor feature

Common sites

Percentage malignant

MEN associated

Insulinoma

Neuroglycopenia (confusion, fits)

Permanent neurological deficits

Pancreas (β-cells)

10

10%

Gastrinoma (Zollinger–Ellison syndrome)

Peptic ulceration

Diarrhoea, weight loss, malabsorption, dumping

Pancreas Duodenum

40–60

25%

VIPoma (Werner–Morrison syndrome)

Watery diarrhoea, hypokalaemia, achlorhydria

Hypercalcaemia, hyperglycaemia, hypomagnesaemia

Pancreas, neuroblastoma, SCLC, phaeochromocytoma

40

<5%

Glucagonoma

Migratory necrolyic erythema, mild diabetes mellitus, muscle wasting, anaemia

Diarrhoea, thromboembolism stomatitis, hypoaminoacidaemia, encephalitis

Pancreas (α-cells)

60

<5%

Somatostatinoma

Diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, steatorrhoea, malabsorption

Anaemia, diarrhoea, weight loss, hypoglycaemia

Pancreas (β-cells)

66

Case reports only

Pancreatic endocrine tumours

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree