Fig. 6.1

Axial contrast-enhanced arterial phase MDCT demonstrates dilatation of the distal common bile duct (*) due to isoattenuating adenocarcinoma (arrow) of the pancreatic head. The main pancreatic duct of body and tail is not dilated (not shown) due to a compensating Santorini duct (curved arrow)

MDCT can help in the assessment of the „T parameter”. In particular, infiltration of retroportal fat tissue can be assessed by MDCT with 80% sensitivity and 84% specificity according to some authors.

Vascular assessment is very important to define the surgical strategy and define „borderline resectable pancreatic tumors” (BRPTS). In BRPTS, current protocols advise neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy. MDCT allows assessment of the vessels, and extensive analyses of the MDCT findings may help to define „true” BRPTs.

One interesting study found that preoperative assessment of body-fat distribution by MDCT, as a surrogate for fatty pancreas infiltration, can help to predict clinically significant pancreatic fistulas after pancreaticoduodenectomy [3].

Many cases of suspected or established pancreatic cancer undergo MRI assessment for further evaluation after MDCT. MRI protocols for the assessment of the pancreas have been expanded with the inclusion of different sequences. The sequence that has been investigated and used most widely in recent years in oncologic imaging is diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). DWIMRI permits measurement of the diffusion of water in tissues and quantification of this parameter as apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). The images that can be obtained with DWI MRI are similar to those of PET-CT and, in fact, in many clinical settings, DWI-MRI is challenging PET-CT in oncologic imaging.

Cystic pancreatic lesions are readily detected at imaging and their assessment has been focused on differentiating malignant from benign lesions, DWIMRI can aid in the assessment of these types of lesions. Boraschi et al. found that the mean ADC values of different types of pancreatic lesions (intraductal papillary mucinous tumor (IPMT), mucinous cystoadenoma, serous cystoadenoma, pseudocyst) were significantly different (P<0.05). Therefore, the authors concluded that DWI-MRI may be helpful in the differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions [4]. In the work of Sandrasegaran et al., ADC values were found to be helpful in deciding the malignant potential of IPMT. However, ADC values were not useful for differentiating malignant from benign lesions, or for characterizing cystic pancreatic lesions [5].

In pancreatic adenocarcinoma, DWI-MRI can be added to standard MRI protocols and, although the lesion may not be clearly delineated in ≤47% of cases, signal alteration in the pancreas distal to the malignant lesion may provide an adjunct sign for the classic radiological findings in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Other authors have also found limited improvement with DWIMRI compared with MDCT in the detection of pancreatic cancer in a high-risk population with main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation. Instead, DWI and T2- weighted images used together may help in the depiction of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors that, in some cases, may be difficult to identify with standard MRI sequences.

In our experience, DWI may help in the diagnosis of intrapancreatic spleen, which can be readily confused with a neuroendocrine lesion of the pancreatic tail. In these cases, the ADC of the intrapancreatic spleen is the same as that of the spleen.

An interesting use of DWI is in the assessment of pancreatitis caused by pancreatic cancer (Fig. 6.2), DWI can, in some cases, be used to detect a malign pancreatic lesion with restricted water diffusion within the edematous pancreatic parenchyma with the increased water diffusion (due to increased water content) related to pancreatitis.

Fig. 6.2

Axial DWI MRI shows a high signal in the pancreatic head that had a low ADC (not shown). This finding is compatible with a diagnosis of pancreatitis due to cancer (arrow) of the pancreas head

ADC measurements can also be helpful for differentiating between normal pancreatic tissue and mass-forming focal pancreatitis. However, the overlap in ADC values of pancreatic cancer and mass-forming focal pancreatitis does not allow their correct distinction in real-world practice [6].

DWI may also aid in the identification of lymph nodes but not in the definition of a „true” metastatic lymph node. Furthermore, often metastatic lymph nodes are of very small diameter (3 mm) and are therefore difficult to detect.

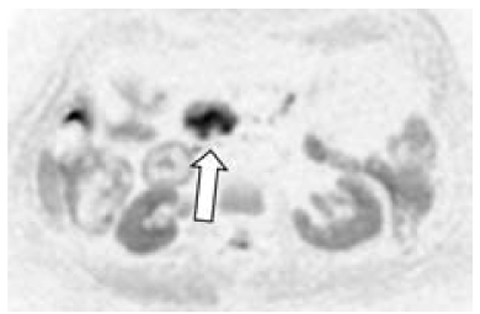

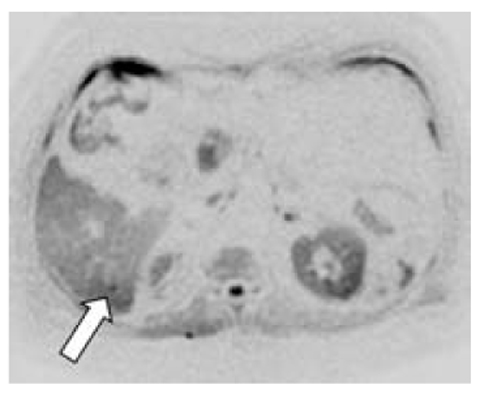

In a pilot study, DWI performed significantly better than contrast-enhanced 64-slices MDCT in the detection of liver metastases in patients with pancreatic tumors. Therefore, DWI may help to optimize therapeutic management in such patients in the future (Fig. 6.3) [7]. In the assessment of hepatic metastases, hepatobiliary contrast agents may be helpful (Fig. 6.4), These contrast media are widely used because they cannot be taken up correctly in the delayed hepatobiliary phase by pancreatic metastases (in general, by all liver metastases).

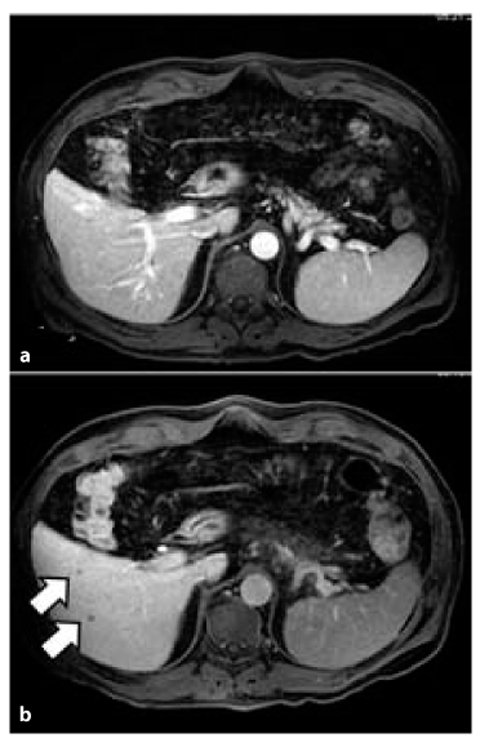

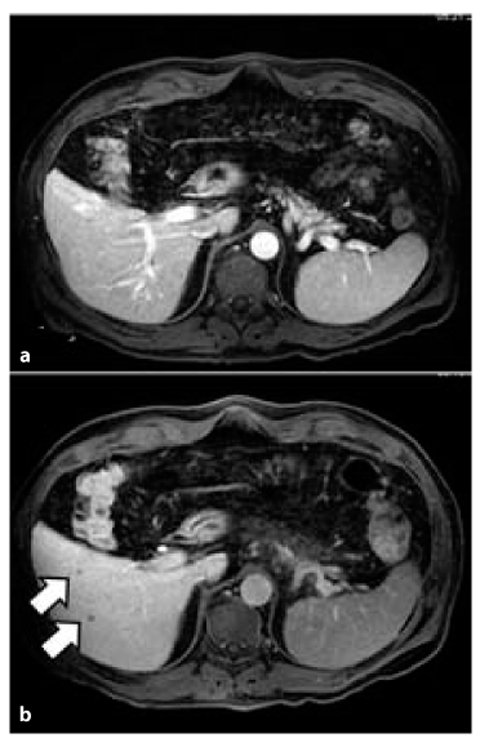

Fig. 6.3

Small metastasis (arrow) of pancreatic adenocarcinoma visible only in DWI MRI in hepatic segment VI

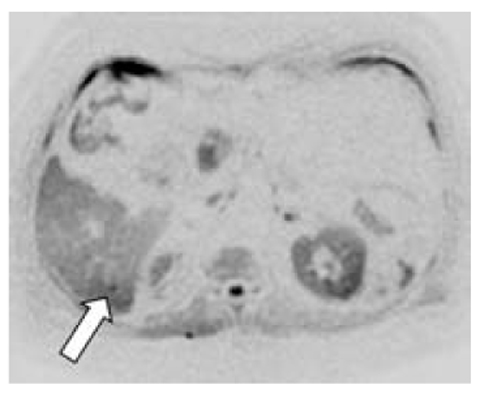

Fig. 6.4

Two small metastases (arrows) of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in segments V and VI. They are hard to identify on portal phase images (a) but readily depicted as hypointense lesions in the hepatobiliary delayed (80 min) image after intravenous injection of contrast media (b) (gadobenate dimeglumine)

In our experience, DWI can be used to depict the small foci of peritoneal carcinomatosis that may be unrecognized on standard MRI sequences and MDCT.

Unenhanced MRI can be used to evaluate vascular structures with the use of particular sequences. This elicits results that can be compared with those of contrast-enhanced MRI vascular studies. This research field is being developed. In general, state-of-the-art contrast-enhanced MRI and contrastenhanced MDCT protocols should be substantially equal in the assessment of pancreatic cancer.

PET-CT has had a small impact in the management of pancreatic cancer. According to some authors, the improvement in PET-CT devices (and particularly the use of iodated contrast media) allows better results [8].

In conclusion, imaging has shown significant improvements in the assessment of pancreatic cancer, particularly in view of pancreatic surgery. A close correlation between imaging as well as clinical and endoscopic findings (including endoscopic ultrasound) is often needed to establish the correct treatment.

Surgical Treatment: an Overview

Pancreatic tumors are a challenging problem for surgeons. Many authors have discussed the indications and extent of surgery, the value of lymph-node dissection, vascular resections, As well as minimally invasive approaches to neoplastic diseases of the pancreas.

Surgical Methods

The Whipple-Kausch pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PP-PD) are the treatments of choice for tumors of the pancreatic head. Both procedures comprise resection of the pancreatic head together with the duodenum, with (PD) or without (PP-PD) distal gastrectomy. The reconstruction of the biliary and alimentary tract is usually undertaken with a gastro-jejunal anastomosis (PD) or a duodeno-jejunal (PPPD) anastomosis and a biliary anastomosis between the hepatic duct and jejunum. A recent review demonstrated no differences among the two methods with regard to morbidity, mortality and overall survival. PP-PD is superior in terms of intraoperative blood loss and operating time. Most authors carry out duodeno-jejunal anastomosis in the antecolic position [9].

Lymphadenectomy

The value of extended lymphadenectomy is controversial. There have been many debates about the results of extended lymphadenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head [10]. The conclusion of these articles is that extended lymphadenectomy does not benefit long-term survival and no further studies are required to assess this issue.

Pancreatic Reconstruction

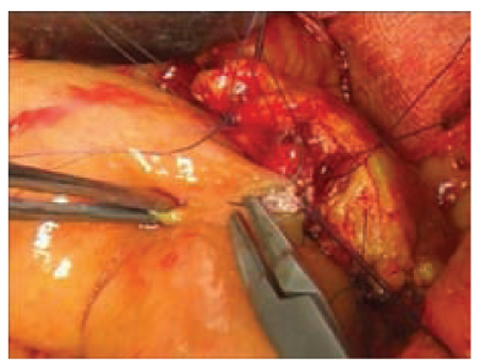

Many authors have discussed the type of anastomosis in the pancreatic and alimentary tracts. Two reconstructions are used: pancreatogastrostomy and pancreaticojejunostomy. The main issue is the prevalence of pancreatic fistulas, the „Achilles’ heel of pancreatic surgery”. In this regard, many studies have been conducted without evidence of the superiority of one type of anastomosis over another. Berger et al. [11] found a lower rate of fistulas with invagination of the pancreas in the jejunal loop with respect to the duct to the jejunum anastomosis (Fig. 6.5). Peng et al. described promising method called a „binding pancreaticojejunostomy” [12]: an end-to-end anastomosis with invagination of the pancreas in a jejunal loop in which the mucosa was previously cauterized. Somatostatin seems to have a prophylactic function with respect to postoperative morbidity and fistula formation [13].

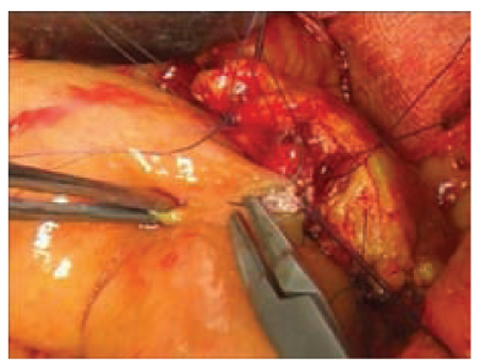

Fig. 6.5

Duct-to-mucosa Wirsung jejunal anastomosis

With regard to stenting of the MPD, external stents seem to have a better outcome in terms of postoperative complications and pancreatic fistulas compared with internal stents or no stent, but further studies are required [14]. In conclusion, given the relatively high rate of complications in this type of surgery, the choice of pancreatic anastomotic method should be based on individual experience, and the best anastomosis after PD is based upon the preference and experience of the surgeon [15].

Vascular Resection

Several studies have been conducted to assess the results of vascular resections to achieve R0 margins during PD for advanced adenocarcinoma with vascular involvement. Even if vascular resection can be achieved safely, the overall 3-year survival in PD with vascular resection shows no differences from PD without vascular resection [16]. In a retrospective analysis of 3,582 patients undergoing PD for malignant disease, Castleberry et al. [17] demonstrated increased 30-day morbidity and mortality in PD associated with vascular resections.

Laparoscopic Surgery

Laparoscopic approaches to pancreatic-head tumors are controversial. The criticism originates from the prolonged operating time and the often reduced accuracy in dissection and reconstruction time. Several authors have reported small series of laparoscopic PD, and showing no substantial advantages of minimally invasive surgery (MIS). Looking to the future, widespread and less expensive propagation of robotic-assisted laparoscopic methods could provide a sense of MIS approach in this field.

In a recent study with 15 patients [18], the morbidity, mortality and incidence of pancreatic fistulas seemed to be similar to those reported for open or laparoscopic surgery, as well as the number of lymph nodes collected. Compared with a laparoscopic approach, robotic surgery seems to have a lower conversion rate, blood loss and operating time as well as better oncological results [19]. MIS applied to the treatment of distal tumors of the pancreas (body and tail) has shown encouraging results primarily due to increasing experiences of many researchers worldwide.

In the early days of MIS for distal pancreatic lesions, the indications were limited strictly to benign and borderline diseases (cystic tumors, neuroendocrine tumors). However, authors are now reporting on malignant tumors treated by this approach. The advantages of MIS are less blood loss, reduced postoperative morbidity and hospital stay.

Venkat et al., in their meta-analysis of 1,814 patients, reported similar oncological results and margin-free resections [20]. Moreover, recent retrospective studies from Fox et al. highlight the lower cost (postoperative and total) in the laparoscopic group compared with open pancreatectomy [21].

A matter of concern is the possibility of spleen preservation, which seems to be higher in MIS of the distal pancreas. Two methods can be used to save the spleen. The first involves dissecting out the splenic artery and vein with division between the pancreas and the splenic artery and vein. The second is by resecting the splenic vessels along with the pancreas but with careful preservation of the vascular collaterals in the splenic hilum, which allows the spleen to survive on the short gastric vessels (Warshaw method). Only retrospective studies are available regarding this issue. However, these studies seem to confirm that spleen preservation gives a lower morbidity rate compared with splenectomy associated with this type of pancreatic resection. Distal pancreatectomy plus splenectomy seems to impair postoperative pancreatic leaks, fatigue, cold or flu. Tsiouris et al. noticed more pancreatic leaks in a spleen-preserving group [22]. With regard to the method (splenic vessels resection vs vessel preservation), postoperative complications were not different between the two groups; a low occurrence of perigastric varices was detectable in the splenic vessel resection group.

In distal pancreatectomies, robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery seems to allow promising results in terms of the accuracy of surgical field dissection, harvesting of lymph nodes, blood loss and postoperative recovery due to the well-known advantages of robotic movements. In the next few years we will surely observe propagation of these methods, and obtain results from larger series.

Ablative Methods

Some investigators have assessed the feasibility and complications of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) applied to pancreatic tumors that are suitable for complete resection. Complications are related mainly to thermal injuries to the nearest organs, such as the biliary tract, duodenum, portal vein and transverse colon, and the prevalence of such injuries is ≈24%. Promising results have come from the association of RFA with radiochemotherapy or systemic chemotherapy: median survival is 25.6 months with an intra-abdominal morbidity rate of 26.2% [23].

Preoperative Radiotherapy for Borderline Resectable and Unresectable Disease

A preliminary consideration on the use of preoperative radiotherapy is to discriminate between localized resectable disease and unresectable advanced tumors. This is because treatment goals and consequent treatment approaches will be different between the two groups of tumors with regard to the choice of chemotherapy association (i.e., with 5-Fluorouracil (5FU), capecitabine or gemcitabine) and the treatment dose and volume of radiotherapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree