Fig. 15.1

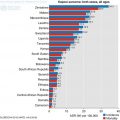

Reach of Palliative care in Africa. Courtesy Anne Merriman, Hospice Africa Uganda, 2016

The program has an English, French and bilingual teams but also intervenes in countries with other official languages as Ethiopia, Tanzania and Sudan. (Hospice Africa Uganda 2016). Other education and training providers include national palliative care associations, palliative care organizations, Universities and global organizations. APCA is a pan – African organization ensuring that palliative care is widely understood, integrated into health systems at all levels and underpinned by evidence in order to reduce pain and suffering across Africa (African Palliative Care Association 2016).

15.3 Best Practice

The thrust of palliative care is that both curative and palliative intent should proceed simultaneously from early in the course of any life limiting or life threatening illness. As the possibility of cure diminishes, palliative care should increasingly become the major focus progressing to end of life care, death and bereavement support (Fig. 15.2).

Fig. 15.2

Continuum of care

Internationally, palliative care is identified as an essential component of care and support for all age groups including children, the elderly, patients with cancer, HIV/AIDS, neurodegenerative and other non-communicable diseases. For cancer, palliative care is applicable alongside anticancer treatments such as chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy while investigative procedures are kept to the barest essential ones in advanced disease. Unfortunately, all these services are poorly developed in sub- Saharan Africa and multidisciplinary tumour boards are almost non-existent.

Hospice and palliative care services are an important part of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), aiming to relieve suffering and to improve quality of life for adults and children affected by life-threatening and life-limiting illness. Thus, international organizations recommend that all governments integrate palliative care into their country’s health system, alongside curative care (Economist Intelligence Unit 2010). At a minimum, palliative care should be provided even when curative care is unavailable. To effectively integrate palliative care into a society as a public health issue and change the experience of patients and families, the four components of the WHO Public Health Model must be addressed. There must be (1) appropriate policies, (2) adequate drug availability, (3) education of health care workers and the public, and (4) implementation of palliative care services at all levels throughout the society (Stjernsward et al. 2007).

15.3.1 Current Practice

Current practice of palliative care involves a team of trained interdisciplinary teams consisting of professional nurses, nursing assistants, doctors, social worker, pharmacists and chaplain collaborating with other disciplines including art, music, physical, occupational therapists and also volunteers. They provide care across all health settings (hospital, clinic, home, nursing home, rehabilitation centres, community programmes and hospices). Service ensures effective management of pain and other distressing symptoms while incorporating psychosocial and spiritual care with consideration of the needs, preferences, beliefs and culture of patients and their families. Such care should also meet the economic needs of the people. Currently, most of the countries in SSA just practice the hospital and home-based care model of service provision – built around trained health professionals, family care givers and community-based volunteers. Such circumscribed coverage does not address all the components of the WHO enhanced public health model.

The model at Hospice Africa Uganda has provided valuable training and clinical template for several African countries. In Nigeria, home based care is offered in collaboration with a non-governmental organization and services include pain and other symptom control, counselling and training for carers at home, provision of funds and comfort packs, bereavement services (Omoyeni et al. 2014). Best practice in palliative care should ensure that:

Patients, families and health care providers communicate and collaborate about patient care needs

Care is coordinated across the continuum of care

Palliative care services are available concurrently with curative or life prolonging care

Patient and family hope for peace and dignity are supported throughout the course of illness, during the dying process and after death.

Pain is the major distressing problem in patients presenting for palliative care in SSA. According to WHO data, and from the experience of palliative care providers in the region, about 552,100 people died of cancer in sub-Saharan Africa in 2009 and studies have shown that roughly 80% of deaths from cancer need pain treatment (Omoyeni et al. 2014; World Health Organization 2011; World Health Organization 2008). Opioid analgesics are also used for pain in AIDS and other patients who suffer from both acute and chronic pain. However, consumption of opioid analgesics in the region is low and data suggest that at least 88% of cancer deaths with moderate to severe pain are untreated. Recent initiatives characterized by cooperation between national governments and local and international non-governmental organizations (American Cancer Society treat pain program and pain free hospital Initiative) are improving access to pain relief. Such efforts in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria and Ethiopia provide examples of challenges faced and innovative approaches adopted to improve access to pain relief for patients (Foley et al. 2006; O’Brien et al. 2013; Soyannwo 2012).

Funding necessary to cover essential palliative care services usually exceeds the financial means of individual patients, families and even that of many developing countries. The cost of treatment and care vary based on the severity and complexity of the illness and use of advanced therapies to manage symptoms. In addition, indirect costs are associated with cancer morbidity, such as days lost from work for the patient or caregiver. Non-monetary costs associated with pain, suffering or loss of companionship is difficult to measure but they are very real to patients and their families (Soyannwo 2010).

15.4 Barriers

Several factors including socio-cultural interplay in SSA and constitute barriers to effective palliative care delivery for cancer. Traditional healers and herbal medicine sellers are often the first place of call for help in any illness including cancer. Late recognition of initial symptoms, dismissing symptoms, search for alternate treatment and cure, inappropriate advice, false hope, poverty and fear of hospitals are common issues. International Association for Hospice and Palliative care (IAHPC) categorized the key constraints and barriers to palliative care in developing countries into five different levels: community and household level, health service delivery, health sector policy and strategic management level, public policies cutting across sectors and environmental characteristics (De Lima and Hamzah 2004). Recently, major social barriers identified with breast cancer patients in Nigeria include lack of education, using non-physician medical services such as pharmacists, fear of anticipated surgery, cost and belief in spiritual affliction as the cause of cancer (Pruitta et al. 2015). Shortage of health care professionals and access to palliative care teams are handled in some countries like Uganda by training specialist palliative care nurses to prescribe oral morphine for patients with moderate to severe pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree