Margred M. Capel

Palliative Medicine for the Older Patient

This chapter will define palliative care and consider it in the context of the older patient. In addition, it will briefly consider the impact of age and frailty on the illness, its social impact, and the strategies available. The second part of this chapter will concentrate on symptom control.

Introduction

The hospice movement arose out of religious orders in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although arguably it has been practiced by medical practitioners in some form throughout history.1,2 However, it was Cicely Saunders pioneering work that brought the advances in pain and symptom control, leading to the special skills known as modern palliative care.

Death is an inevitable consequence of life; increasing life expectancy and altered disease trajectories mean that death from disease occurs more commonly in older adults. In developed countries, older adults may be affected by multiple coexisting acute and chronic illnesses. The annual number of worldwide deaths is expected to rise by 2030, an increase that is expected to occur through conditions related to organ failure and physical and cognitive frailty.3 In the twenty-first century, palliative medicine aims to ensure that the dying process itself does not have to be the excruciating struggle that many older adults remember from when their grandparents died.

Palliative medicine can have an important role when patients are entering their last days of life, but it also can contribute to ameliorating the quality of life of patients suffering from chronic or intractable disease.1,2 Palliative care is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as follows: “Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”4

The Aging Process

Illnesses and coexisting morbidities encountered in older adults differ from those encountered in the young. The consequence of the aging process can mean that patients have coexisting cardiac, metabolic, and rheumatologic disorders (e.g., ischemic heart disease, diabetes, arthritis) in addition to developing illnesses associated with age itself (e.g., neurodegenerative disorders [dementia, Parkinson disease], stroke, cancer). The prevalence of failing organ function, such as heart failure and renal failure, can impose significant physical and psychological distress on the individual, restricting activities and quality of life of the patient and caregiver. In addition, the abnormal health state of frailty will contribute significantly to general weakness and fatigue. Frailty in this context refers to those who demonstrate progressive weakness and deterioration in their overall functional ability. Their decline may not correlate with their comorbidities, but they often lack the reserve to tolerate stressors such as intercurrent illness, examination, or hospital admission. This group of individuals, however, may experience a significant impact on their quality of life, undergo multiple hospital admissions, and incur significant amounts of health care and direct and indirect social care costs.5,6

Providing palliative care to older patients with frailty or chronic illness may mean that at different stages of the illness, the patient may require preventive or life-prolonging intervention, rehabilitation, or purely comfort measures, depending on the needs of the individual that are identified and their place along the illness journey. Recognition and shifting emphasis of care toward a goal-directed care may require sensitive communication with the patient and their care providers.7,8

The aging process alters organ function, which affects the pharmacokinetics of drug metabolism.6,7 Pharmacodynamic processes are also affected by age, with some receptors (e.g., benzodiazepine, opiates) demonstrating greater sensitivity and others (e.g., insulin) having comparative insensitivity. The presence of coexisting disease risks compounding this through the consequences of polypharmacy.7,9–11

Care Providers

Cultural, ethnic, and social differences exist within communities, affecting the availability of support and expectations of care for the patient. The burden of home care falls mainly on female members of the family, and the intensity and economic costs can compare with those incurred by formal care provision.2,12–15 A minority of care of older adults is from paid caregivers. In addition to spouses providing care for their partners, in the absence of spouses or in the event of their ill health, children often provide care for their older parents. This role reversal affects relationships and caregivers’ physical and psychological health and has economic consequences.12–15 Care providers have an increased risk factor for death, significant physical ill health, and depression.

Care providers of the older patient need increased support from the medical team during episodes of acute illness of the patient and ongoing support during chronic stages, which may require them to provide care over many years.12–16 Care providers need full explanations of the disease processes to help manage their expectations and help them cope with the uncertainty that ill health brings.

The umbrella of palliative care may entitle patients and care provider’s access to financial and social resources to help alleviate the economic and social burdens of care provision. Access to a day center or sitting service may provide some respite to the care provider. Respite care should be considered if the care provider has acute health needs and at planned regular intervals to provide a break from the work of caring. Unrelieved stress and the burden of care can otherwise result in a breakdown in the relationship between the care provider and patient, potentially spiraling down into situations of neglect, abuse, and worsening health in both parties.14,15

Care providers frequently have concerns and feeling of guilt when the patient is being cared for in a nursing or residential home environment so they need to be listened to and, when necessary, reassured of the reasons for the appropriateness of place of care. Often, those who have cared for a patient for a long time want to continue to provide some care when the patient is transferred to a nursing home or hospice facility. Helping them do this can relieve the burden of guilt and worry that they feel from relinquishing care in the home environment.

Following the death of the patient, the care provider may experience severe grief for the profound loss they have experienced and for their loss of this role in addition to readjusting to life and organizing funeral arrangements and financial affairs. Such individuals are at risk of prolonged or complicated bereavement and referral to bereavement support groups and counselors may be beneficial, depending on the individual’s support network and coping strategies.

Future Planning

The importance of forward planning with older patients and their families or care providers cannot be underestimated. This can prevent considerable distress and disagreement if family members or care providers have to make decisions concerning health and social care when the patient is unable to do so. Many primary care practices and care facilities actively encourage Advance Care Planning (ACP) to explore, address, and record these discussions when patients are recognized to have significant comorbidities, frailty, or life-threatening illness. These discussions may require several meetings to cover all the relevant areas the patient wishes to explore and can benefit from the health practitioner who is most familiar with the individual taking the lead during the discussion and in future coordinated care delivery.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (England) directs medical teams to consider the information provided by individuals who are familiar with the patient in the event that the patient is unable to communicate her or his wishes. The responsibility for medical decisions that have to be taken on behalf of a patient who has lost capacity still ultimately rests with the medical team and not the family; an existing ACP can support and inform decision making. In the absence of family or friends, there is provision under the act for a court-appointed patient advocate who may provide input about aspects of social and medical care.16

An advanced decision to refuse treatment is legally binding and enables the patient to consider the recognized complications of his or her illness or dying process, explore treatment options, and communicate future preferred medical management in specific circumstances. The advance decision to refuse treatment can set limits on the interventions a patient would want to refuse in the future—for example, with respect to artificial feeding and nutrition, use of antibiotics, repeated venipuncture, resuscitation, and respiratory support. However, an advance decision cannot direct the clinical team to undertake an intervention if it is not clinically indicated in the patient’s best interest.

The four ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice create a framework within which all clinical decisions should be considered. Autonomy or self-governance requires respect for the individual’s right to determine her or his own well-being; however, to do this, patients require information in a comprehensible format to make informed choices concerning the future. The principle of nonmaleficence means that patients should not be burdened with futile investigations, treatments, or useless information that does not enhance their life. Attempts at cardiopulmonary resuscitation may fall into this category in certain circumstances. Beneficence dictates that the anticipated benefits must outweigh the anticipated risks and burdens of intervention or treatment. Justice implies that all patients may have similar access to investigations and treatments, without prejudice. It also implies that they may have the best possible care with the resources available, but these have to be fairly allocated and divided among their community.

The use of ethical frameworks can be applied to decisions regarding withdrawal of active treatment to achieve the appropriate choice for the individual and prevent unethical blanket policies.

Place of Care

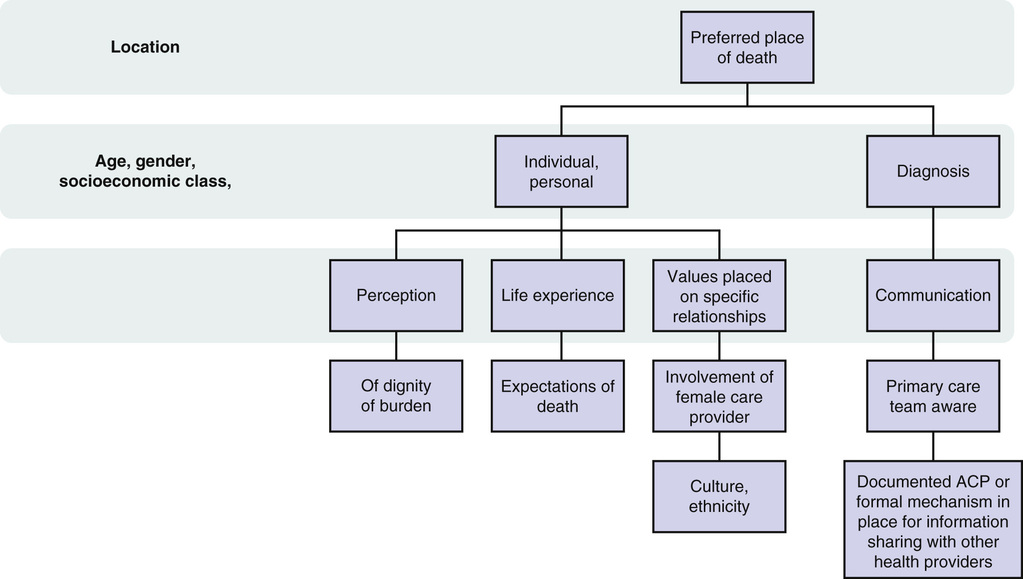

The preferred place of care throughout life and when dying should be explored sensitively and honestly, making the older patient aware of feasible options and their limitations. Inequalities of access to home care nursing exists throughout the United Kingdom and can preclude care at home. Patients are recognized as being able to change their preferences during their illness journey. Factors recognized to influence decision making or preferred place of care are outlined in Figure 114-1.17,18 Primary care teams who keep palliative care registers can use the trigger for completing DS1500 and/or the question: “Would you be surprised if the patient died within the next 6 months?” to identify patients for such a register. The DS1500 is the medical report outlining the terminally ill individual’s condition and enabling him or her to access other financial benefits under special rules. This obviates the requirement of proving what care is needed, having a medical examination, and waiting for a mandatory period of time. In addition to this question, various tools exist to identify patients with palliative care needs, including the Gold Standards Framework (GSF)19 and Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT).20 A register can be used to inform out-of-hours services of the patient’s condition and tailor provision of health care to prevent unwanted or unnecessary admissions to the hospital via the emergency or out-of-hours services.19,20 Use of the GSF in care homes can reduce crisis hospital admissions, decrease the percentage of residents dying in the hospital, and facilitate patient-centered care. ACP should be offered to individuals included in any of these criteria.

Many hospices offer short-term admissions but cannot accommodate people for a prolonged period of terminal illness, which may mean that the individual experiences several admissions throughout the course of the terminal part of their illness. Use of individualized care plans or care priorities can support end-of-life care, encouraging care delivery to be of the highest standard, irrespective of location, and enhance communication.15,17,19

Patients can be considered terminally ill when they are likely to die within the foreseeable future from a specific progressing disease. Older patients often suffer from one or more chronic illnesses and/or frailty, in addition to experiencing progressive disease or receiving a terminal diagnosis, and can benefit from care with a palliative approach, apart from those who are actively dying and within their last days of life. Whenever symptoms occur, the potential cause of the symptom should be identified to guide treatment. Appropriate treatment of the cause may resolve the symptom and improve quality of life, even in the presence of concurrent terminal illness, such as treatment of hypothyroidism, Parkinson disease, or intercurrent infection. Problem-oriented clinical notes prove particularly useful in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Symptom Control

Pain

“Pain is what the patient says it is,” and the same principle apply to treating pain in older adults as in younger patients.2 Each pain should be identified, characterized (including site, duration intensity) and separately recorded, and precipitating and relieving factors identified. Application of the simplistic pneumonic PQRST23 (see later, Key Points) may aid this process. This detailed history may suggest the underlying pathophysiology, which may determine pain treatments and possible disease-modifying interventions. Meticulous physical examination is essential; for example, abdominal pain from urinary retention compared with pain from acute abdomen or a tumor mass may give a similar history but have very different signs. The pain should be considered in holistic terms, including considering the impact this has on the individual because effective control of the physical aspect of symptom control requires consideration and intervention to the social, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of the individual. Pain assessment should include mood and emotional, functional, and cognitive assessment because these are recognized to affect pain perception and, unless addressed, may continue to be manifested as physical pain unresponsive to analgesia. Older patients, in comparison to their younger counterparts, are more likely to experience musculoskeletal, leg, and foot pain and less likely to experience headache and visceral pain (Box 114-1).10,11,24

After a baseline assessment of the pain, the situation should be evaluated every 24 hours until pain is controlled. A variety of tools can be used to assess pain, including the Simple Descriptive Pain Intensity Scale, Numeric Pain Intensity Scale, and Visual Analogue Scale. The Functional Pain Scale has been validated for use in older adults.2,25 Altered behavior or agitation may be a manifestation of pain in patients with impaired communication; there are tools to support accurate monitoring of behavior and, through, this the impact of the introduction or titration of analgesia. Preferably, the tool should be accessible and applicable to the individual, family, and caregiver or staff using it.

Analgesic Titration

Analgesia can be titrated in accordance with the WHO analgesic ladder (Table 114-1), and, depending on the underlying pathophysiology of the pain, appropriate adjuvants can be included in the regimen. Consideration of tablet burden, medication compliance, and comorbidity may indicate that the most simplistic regimen is appropriate, or a blister pack or pill organizer box may need to be considered for a patient at home, with support from the appropriate community services.

TABLE 114-1

Steps of the WHO Classification System for Analgesic Use

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

| Nonopioid ± adjuvant | Weak opioids ± adjuvant ± nonopioid | Strong opioids ± adjuvant ± nonopioid |

| Paracetamol | Codeine | Morphine |

| NSAIDs | Dihydrocodeine Tramadol (Buprenorphine is a mixed agonist-antagonist) | Diamorphine Oxycodone Hydromorphone Fentanyl Alfentanil Methadone |

Paracetamol is appropriate for osteoarthritis or musculoskeletal pains; the dose should be reduced in patients with liver impairment or probable malnutrition. Codeine is a prodrug of morphine. Co-codamol (paracetamol and codeine), 30/500, is an effective analgesic administered every 6 hours; however, variations in metabolism through cytochrome P4502D6 may significantly impair the analgesia available for use. Analgesia should be titrated upward rather than adding an additional drug of the same class or step.

Opioid Analgesia.

Morphine is a recommended first-line step 3 analgesic (see Table 114-1); the dose can be titrated in increments of 30% to 50% until analgesia is achieved.26 There is no ceiling dose for step 3 analgesics; rather, these should be titrated stepwise if the pain responds (i.e., can be demonstrated on assessment to diminish or disappear with analgesia use). The presence of side effects or incomplete resolution of the pain despite opioid use should prompt addition of an adjuvant, if not already begun. In frail older adults whose pain severity indicates that they should go straight to step 3, morphine (Oramorph, 2.5 mg), may be an appropriate starting dose of a step 3 opioids given on a regular 4-hour basis, reflecting the half-life of the drug.

Patients and care providers should be warned about the potential side effects of medication used and, where, possible these should be minimized; these are outlined in Table 114-2. For example a regular stimulant or mixed stimulant-softener laxative is almost always indicated when commencing step 3 strong opioids; about one third of patients will experience opioid-induced nausea, so an antiemetic such as haloperidol may be indicated for the first 7 to 10 days on the drug. Reassurance and explanation is often needed for those patients and care providers who think that the use of opioids could lead to the patient becoming a drug addict or becoming tolerant to the analgesic effect. The dosing interval or choice of opioids is influenced by coexisting organ failure. Persistence of side effects, including drowsiness, may be an indication for opioid rotation. Opioids that are extensively metabolized in the liver and do not accumulate during renal failure, such as fentanyl and alfentanil, would be drugs of choice for patients with analgesic requirements and renal impairment. Fentanyl is poorly orally absorbed and subject to extensive first-pass metabolism but is well absorbed from the oromucosal, transdermal, intranasal and subcutaneous routes. However, the patch or transdermal route is a comparatively inflexible route of drug delivery and is not suitable for a patient with unstable pain or rapidly escalating requirements; in such situations, subcutaneous administration may be needed.

TABLE 114-2

Side Effects of Strong Opioids

| System | Symptom | Action to Be Considered |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea and vomiting Hiccup Constipation | Prophylactic antiemetic Prokinetic antiemetic Concomitant use of laxative |

| Increase smooth muscle tone | Urinary retention | Monitor for this symptom |

| Allergy through histamine release | Urticaria, bronchoconstriction and dyspnea, itching | Alternative opioid preparation, or antihistamine and bronchodilator depending upon context and severity |

| Centrally mediated phenomenon of itch | Whole body itch or can be localized with spinal morphine | May respond to use of serotonin antagonist |

| CNS | Multifocal myoclonus Cognition, sedation, vivid dreams Delirium and hallucinations | Exclude other causes, consider dose reduction use of benzodiazepine, or alternative opioid May resolve within few days of starting Check renal and liver function, consider dose reduction or alternative opioid Consider dose reduction, use of haloperidol or use of alternative opioid |

| Respiratory | Antitussive |

The signs of fentanyl excess in older adults can initially be more subtle than those typically associated with morphine excess. In fentanyl toxicity, care providers may report that the patient is quieter and more sedentary than usual, whereas morphine toxicity usually causes drowsiness, confusion, hallucinations, grimacing, pinpoint pupils, slowed respiratory rate (respiratory depression), twitching, and myoclonus. Allodynia and hyperalgesia, are occasionally seen as a paradoxic hyperalgesia, but often their presence indicates a neuropathic pain that is only partly opioid-sensitive. Comparisons of equivalent doses of steps 2 and 3 opioids are available, and they should be applied when switching opioids.26,27

The route of drug delivery depends on the patient’s condition and ability to ingest, retain, and absorb oral medication. Potential routes of drug delivery in frail palliative care patients include the oral, rectal, buccal, transdermal, and subcutaneous routes. Subcutaneous routes (including infusions and injections) are less painful than intramuscular injections and attenuate the rapid tolerance that may develop with repeated use of the intravenous route, making the subcutaneous route the parenteral route of choice. In cachectic patients, several drugs can be combined with use of a syringe driver; compatibility tables demonstrate which medication and concentrations can be combined safely.28,29

Diamorphine is preferred in the United Kingdom for subcutaneous administration because it is highly soluble, so a high concentration can be given in a small volume. However, in many countries, it is not available, and morphine is the drug of choice. When analgesia is obtained that controls ongoing or background pain, provision must still be made for short-acting analgesia to be available to ameliorate any breakthrough pain.

Types of Pain

Breakthrough Pain.

Breakthrough pain is any pain that occurs over and above a background of well-controlled pain. This is a different entity from that in patients who have an increasing analgesic requirement that increases over time because of underlying disease progression, rather than tolerance.29 Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) lozenges or dispersible tablets can be applied to the patient’s moist oral mucosa to provide rescue analgesia for breakthrough pain as the drug is absorbed transmucosally. Fentanyl or alfentanil preparations are also available via an inhaler or nasal delivery system, but specialist supervision is suggested for the initial test dose. This is because drug delivery is rapid but comparatively short-lived, making this useful for pain associated with movement or dressing changes. Theoretically, any short-lived opioid may be given in advance if the pain is predictable in nature. Pain that occurs unpredictably requires accurate diagnosis of the cause of the pain and interrupting the pathologic process, when possible; if not possible, adding an adjuvant medication or increasing the background dose of opioids may be helpful.

Bone Pain.

Bone and joint pain may respond to adjuvant analgesia, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which have a synergistic effect with paracetamol. NSAIDs should be prescribed with caution for patients already taking aspirin, steroids, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding), diuretics, or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, among others, because these increase the risk of renal failure.

In malignant disease, bone metastases can erode the bone cortex. This can be identified on plain radiographs. Prophylactic surgical intervention may prevent subsequent pathologic fracture. Radiotherapy provides analgesia in 80% of patients with pain from bone metastases and can be considered for frail individuals.1,2 Patients with multiple bone metastases, in the absence of spinal cord compression and with a prognosis longer than 6 weeks, may benefit from radioactive isotope injection (e.g., strontium). Bone pain, particularly from breast, myeloma, or prostate primary, may respond to infusions of intravenous bisphosphonates, despite a normal calcium level, and there is some evidence that bisphosphonates protect against bone metastases in certain cancers (e.g., breast).30,31 Fractured bones should always be immobilized, if possible. If immobilization is not possible, local injection into the fracture site with Depo-Medrone (methylprednisolone acetate), 80 mg, and bupivacaine hydrochloride, 0.5%, may provide sufficient relief to allow the patient to be turned in the last days of life. An alternative would be an interventional anesthetic procedure and nerve block to the area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree