Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Surgical resection offers the best opportunity for prolonged survival but is limited to patients with locally resectable disease without distant metastases. Regrettably, most patients are diagnosed at a point in which curative surgery is no longer a treatment option. In these patients, management of symptoms becomes paramount to improve quality of life and potentially increase survival. This article reviews the palliative management of unresectable pancreatic cancer, including potential palliative resection, surgical and endoscopic biliary and gastric decompression, and pain control with celiac plexus block.

Key points

- •

Palliative surgical resection resulting in grossly positive margins offers no survival benefit and is not recommended for patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer.

- •

Endoscopic biliary stenting and operative biliary bypass are both effective in relieving biliary obstruction without significant differences in mortality or overall survival.

- •

Prophylactic gastrojejunostomy should be performed at the time of hepaticojejunostomy, given a significant decrease in the incidence of postoperative gastric outlet obstruction without an associated increase in postoperative morbidity or mortality.

- •

Celiac plexus block improves pain control and decreases narcotic pain medication usage for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, resulting in few long-term adverse side effects.

Background

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States with a 5-year all-stage overall survival of only 6%. This dismal survival rate is in part attributed to a delay in diagnosis given limitations in disease screening and nonspecific symptoms. Most patients are often asymptomatic or present with vague, nonspecific symptoms, such as weight loss, abdominal pain, fatigue, or jaundice, so that when they are finally diagnosed, the disease is often progressed and has spread to distant organs, limiting treatment options. Currently, surgical resection provides the best opportunity for survival, but is limited to patients with locally resectable tumors without distant metastases. As a result, only 15% to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer present with tumors amenable to surgical resection, creating a large population of patients in whom treatment options are limited. In addition, the local and distant spread of disease often creates symptomatic problems such as pain or obstruction, necessitating treatment for palliation of symptoms. This article reviews the current palliative treatment options in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, including palliative resection, surgical and endoscopic biliary and gastric decompression, and pain control with celiac plexus block.

Background

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States with a 5-year all-stage overall survival of only 6%. This dismal survival rate is in part attributed to a delay in diagnosis given limitations in disease screening and nonspecific symptoms. Most patients are often asymptomatic or present with vague, nonspecific symptoms, such as weight loss, abdominal pain, fatigue, or jaundice, so that when they are finally diagnosed, the disease is often progressed and has spread to distant organs, limiting treatment options. Currently, surgical resection provides the best opportunity for survival, but is limited to patients with locally resectable tumors without distant metastases. As a result, only 15% to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer present with tumors amenable to surgical resection, creating a large population of patients in whom treatment options are limited. In addition, the local and distant spread of disease often creates symptomatic problems such as pain or obstruction, necessitating treatment for palliation of symptoms. This article reviews the current palliative treatment options in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer, including palliative resection, surgical and endoscopic biliary and gastric decompression, and pain control with celiac plexus block.

Current treatment of unresectable pancreatic cancer

Surgical resection offers the best opportunity for prolonged survival and the only chance for potential cure in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Five-year survival rates approach 25% in published series at specialized centers. However, very few patients present with disease at a stage in which curative resection can be effectively offered. An analysis of 58,655 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 1977 and 2001 demonstrated only 8.9% had localized disease compared with 22.4% who presented with regional spread and 49.5% with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, including an additional 19.4% who were unstaged. Looking at the specific period between 1997 and 2001, only 7.4% presented with localized disease compared with a known 25.8% with regional disease and 49.8% with distant metastases. Even without taking into account those with unstaged disease or delineating which patients with regional spread of disease were unresectable, at least half of all patients presenting with pancreatic cancer are unresectable at diagnosis because of the presence of distant metastases.

In addition to distant disease, current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines define unresectable pancreatic tumors as those with greater than 180° encasement of the superior mesenteric artery or celiac artery, superior mesenteric vein or portal vein occlusion not amenable to reconstruction, invasion of the aorta, or the presence of nodal metastases beyond the field of resection. Even in patients with small pancreatic cancers and no evidence of distant metastases, a proportion will be deemed unresectable based on the tumor’s location to vital vasculature. Advances in surgical technique in recent years have allowed for pancreatic resection with portal vein resection and reconstruction at specialized centers in patients with borderline disease. However, although this has increased the number of patients in whom pancreatic resection is possible, most patients are still not surgical candidates.

The main treatment currently for patients with locally unresectable and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma is chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Studies have shown a modest survival benefit with the addition of chemotherapy and radiation in these patients compared with no treatment. In patients with locally advanced, unresectable cancers, median survival ranges between 11 and 15 months in recent reports for patients undergoing treatment with chemotherapy and radiation. In patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, overall survival is much lower and 5-year survival is estimated at only 2%. First-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer often involves gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. Randomized trials of different chemotherapeutic regimens have not demonstrated much of a survival increase beyond a median survival of 5 to 8 months. However, the addition of abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) before gemcitabine treatment in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer has been shown in a randomized clinical trial to substantially increase median overall survival compared with gemcitabine alone (8.5 months vs 6.7 months, respectively). In addition, patients treated with a gemcitabine-abraxane combination had significantly increased median progression-free survival compared with gemcitabine alone (5.5 months vs 3.7 months). Despite an increased incidence of side effects, the combination of gemcitabine and abraxane for metastatic pancreatic cancer has become a common therapy. Furthermore, a recent trial demonstrated significantly longer survival with FOLFIRINOX as compared with gemcitabine in patients with advanced-stage pancreatic cancer (11.1 months vs 6.8 months, P <.001). Compared with the traditional median survival of only 3 to 6 months in this population, this outcome is remarkable and FOLFIRINOX has become a first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Palliative resection

Surgical options are limited for patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Patients with stage IV disease are not considered candidates for surgical resection of the primary tumor. This is in comparison to other cancers, such as colorectal tumors in which a survival benefit has been shown after resection of the primary tumor and metastases. However, there may be some survival benefit for resection in certain patients with recurrent distant disease after the initial pancreatic resection. An analysis of patients with pancreatic cancer with tumor recurrence to the lung demonstrated longer survival after pulmonary metastasectomy for isolated pulmonary metastases compared with a matched group that did not undergo lung resection (51 vs 23 months). Although this study was a retrospective review of patients presenting with metastatic disease months after the initial pancreatic resection, it is an encouraging result for patients with stage IV disease limited to the lungs. In addition, case reports of concomitant pancreatic resection and hepatectomy for liver metastases for pancreatic adenocarcinoma have suggested a survival benefit, with one report including 3 patients alive 2 years after surgery. However, these reports are limited to only a small number of carefully chosen patients. Whether there is a true benefit to resection for metastatic pancreatic cancer remains to be seen.

Even in patients without distant metastases, surgery is not attempted unless the tumor is felt to be completely resectable. Data have been mixed as to whether there is a survival benefit with resection with grossly positive margins, compared with palliative bypass for nonmetastatic, unresectable disease. However, most studies show that there is no clear survival benefit to palliative resection. A retrospective review of 126 patients compared patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) with negative margins, PD with a positive resection margin, or palliative bypass. Most patients in the palliative bypass group had metastatic disease (75%). No significant difference in perioperative morbidity or mortality or readmission was noted among the 3 groups. Although no significant difference was noted between median survival for margin-negative PD or margin-positive PD, median and 1-year survival were lower after palliative bypass than margin-positive PD ( P <.05). However, this survival difference was not seen when comparing margin-positive PD with palliative bypass in only those patients with locally advanced disease. Despite these findings, this study suggested that resection, even with positive margins, was preferable over palliative bypass in patients with unresectable disease.

A smaller retrospective review compared 64 patients undergoing PD with microscopic or grossly positive margins with 62 patients undergoing palliative bypass at a single institution. There was no difference between groups with respect to perioperative morbidity or mortality. Length of hospital stay after operation was shorter in patients who underwent palliative bypass ( P <.05). Overall survival was improved significantly in patients who underwent PD, even with positive margins, as compared with palliative bypass ( P <.02). Given the benefit in survival, the investigators of this study suggested PD was superior to palliative bypass for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, it is important to note that differentiation between microscopic (R1) and grossly (R2) positive surgical margins was not made, which could have biased the survival outcomes in this study.

A systemic review of 4 retrospective studies of 399 individuals with pancreatic cancer compared patients undergoing palliative resection with positive margins to palliative bypass. Patients who underwent margin-positive PD had longer operative times and significantly increased rates of surgical morbidity and mortality compared with patients undergoing palliative bypass ( P <.01 for all). Only one study included postoperative quality-of-life measurements, and patients who underwent palliative bypass were noted to have higher scores. Median survival times were 8.2 months for palliative resection with positive margins and 6.7 months for palliative bypass, comparable between both groups. This study noted the lack of any randomized control studies, but concluded that palliative resection was not advisable given increased hospital length of stay, operative times, morbidity, and mortality without any associated survival benefit. Based on this and other studies, palliative resection leading to grossly positive margins is not advised at this time as a surgical treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Biliary decompression

Most patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma have tumors located in the head of the pancreas. This can lead to biliary and gastric obstruction over time due to tumor location or size, often causing symptoms such as jaundice, pruritus, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. As a result, many patients will require surgical or endoscopic intervention to relieve the obstruction, provide symptomatic relief, and improve quality of life. In patients who are surgical candidates or can tolerate operative intervention, this is accomplished through resection of the primary pancreatic tumor. In patients with known metastatic or unresectable disease or those unfit for anesthesia, however, this requires an alternative approach.

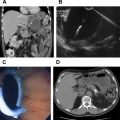

Biliary decompression can be accomplished by endoscopic placement of a stent in the biliary tree or surgical bypass. Endoscopic stenting involves the placement of a plastic or metallic stent into the biliary tree through the area of obstruction. Plastic stents were initially favored, as these could be easily replaced if necessary, but were prone to migration and occlusion. Newer, self-expandable metallic stents are being increasingly used given longer patency and decreased risk for occlusion; however, these cannot be removed after placement. Alternatively, surgical bypass is performed by hepaticojejunostomy, cholecystojejunostomy, or choledochojejunostomy, effectively bypassing the obstruction and creating a direct link between the biliary tree and small bowel. Surgery also may involve concomitant gastrojejunostomy to bypass a gastric outlet obstruction. Although surgery provides definitive relief of the obstruction, it is reserved for patients fit for surgery, often those already undergoing attempted surgical resection, and those with severe symptoms in whom stenting cannot be performed.

Comparisons of surgical bypass to endoscopic stenting demonstrate differences in outcomes but no clearly superior method ( Table 1 ). Most studies are retrospective reviews with a limited number of patients, although a few early, randomized controlled trials were performed to directly compare outcomes between patients undergoing endoscopic stenting or palliative bypass. The first randomized trial of percutaneous biliary drainage and surgical bypass was in 1986, and demonstrated no difference in perioperative morbidity or survival between groups. Three further randomized trials were published before 2000, and continued to show no difference in perioperative mortality or overall survival. However, recurrent symptoms, such as jaundice or cholangitis, were significantly higher at follow-up in patients who underwent stenting, whereas morbidity tended to be higher after palliative bypass and related to the operation. These studies were limited due to small numbers; all but one was limited to fewer than 50 patients total. The most recent randomized controlled trial from 2003 compared 13 patients undergoing surgical bypass for a periampullary cancer with 14 patients in whom endoscopic stenting was performed. This study showed no significant difference among procedure-related morbidity, mortality, readmission, or complications. However, overall survival was longer in the surgical bypass group compared with patients undergoing stenting ( P = .05).

| Author, Year | Procedure | Patient Number | 30-d Mortality, n (%) | Median Survival, wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bornman et al, 1986 | PTE stent | 25 | 2 (8) | 19 |

| Surgical bypass | 25 | 5 (20) | 15 | |

| Shepherd et al, 1988 | Endoscopic stenting | 23 | 2 (9) | 21.7 |

| Surgical bypass | 25 | 5 (20) | 17.7 | |

| Andersen et al, 1989 | Endoscopic stenting | 25 | 5 (20) | 12 |

| Surgical bypass | 25 | 6 (24) | 14.3 | |

| Smith et al, 1994 | Endoscopic stenting | 100 | 8 (8) | 21 |

| Surgical bypass | 101 | 15 (15) | 26 | |

| Nieveen et al, 2003 | Endoscopic stenting | 14 | 0 (0) | Hospital free: 14.1 |

| Surgical bypass | 13 | 0 (0) | Hospital free: 22 | |

| Scott et al, 2009 | Endoscopic stenting | 33 | 6 (18.1) | 19.2 a |

| Palliative bypass | 23 | 1 (4.3) | 54.5 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree