Palliative Care in HIV/AIDS

Peter A. Selwyn

In its beginning phases in the United States in the 1980s, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) care was understood almost fully within the context of palliative care, and many hospice and palliative care clinicians became expert at managing the complex medical, psychological, spiritual, and broader societal issues that were routinely generated by the care of patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS. However in a relatively rapid timeframe—beginning in the late 1980s and accelerating dramatically with the advent of the protease inhibitor class of antiretroviral therapy agents in 1996—AIDS became a “manageable” disease and quickly resulted in a growing medicalization and subspecialization of care which defines the current paradigm of HIV treatment. Although these rapid therapeutic advances,—collectively referred to as highly active antiretroviral therapy, or highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)—have provided great benefit to people living with AIDS, an unintended consequence of the HAART era has been the further separation of HIV/AIDS care from palliative care, and an increasing tendency to dismiss the importance of comprehensive palliative as well as disease-specific therapy for patients with AIDS and their families. The intent of this review is to highlight the many ways in which palliative and disease-specific therapy for HIV can and should coexist in an integrated model in order to meet the complex needs of patients now living with AIDS. Palliative care interventions remain important in the routine care of patients with HIV/AIDS across the continuum of care, not only in order to improve quality of life and address the wide range of medical and psychosocial issues related to chronic, progressive illness, but also to help enhance adherence with HIV-specific therapies, and as a consequence, potentially improve morbidity and mortality as well.

Epidemiology

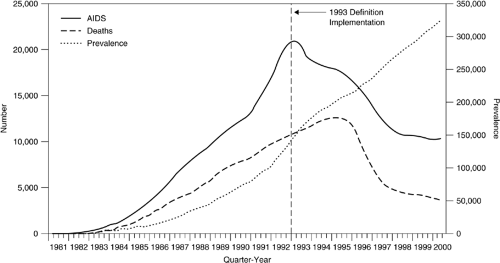

Improvements in antiretroviral therapy, especially with the advent of the protease inhibitor class of antiretroviral agents in the mid 1990s, resulted in dramatic decreases in HIV-related mortality in the developed world, with declines in AIDS death rates of 50–60% in the United States and Europe occurring between 1996 and 2000 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). (Fig. 75.1)). However, several points must be noted:

The rate of decline in death rates has leveled off since 2000, and there remain approximately 15,000 deaths per year in the United States in patients with AIDS (3)

An increasing number of these deaths have resulted not necessarily from end-stage HIV disease but rather from other important and often untreatable comorbidities, such as cirrhosis and liver failure because of chronic hepatic C, hepatitis B, and/or alcohol-related liver disease, as well as non–AIDS-defining cancers which occur in greater than expected frequency in patients with AIDS, such as lung, gastrointestinal, and head and neck cancers. Indeed, in several series, mortality from these non–AIDS-defining comorbidities have accounted for up to 50% of all deaths among patients with AIDS in the past few years (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Of these, hepatitis C is perhaps the most significant, given the high prevalence of hepatitis C among HIV-infected drug users—generally 75% or higher in most series—as well as recent data suggesting more rapid progression to cirrhosis and death in coinfected patients, and the likelihood that drug users as a group may be less likely to receive therapy with interferon and ribavirin than other patient groups (12, 13). In some respects, ironically, it is the prolonged survival with HIV/AIDS in the HAART era that has left patients vulnerable to growing mortality risks from end-organ failure, malignancies, and other chronic, progressive diseases that previously had not posed major risks because patients died before having had the time to develop them (7, 14, 15).

Disparities in access and adherence with HIV-specific antiretroviral therapy have also resulted in differential mortality risk in subpopulations of people with AIDS, such that AIDS-related mortality has diminished less among women, racial-ethnic minorities, and injection drug users than it has among caucasian men, and HIV/AIDS remains a leading cause of death for young African American and Hispanic men and women in the 20–50 year age range (3, 16).

Toxicities from antiretroviral therapies (17, 18, and other challenges to adherence and maintenance of effective treatment regimens over time, have resulted in patients for whom there are few therapeutic options, and in whom antiretroviral therapy may no longer be effective in preventing disease progression and decreasing mortality risk

Overall decreases in AIDS deaths, together with no decrease in the incidence of new HIV infections, have resulted in an increased prevalence of HIV infection, including a larger number of people living with symptomatic HIV disease for longer periods of time (3, 16);

With the bulk of antiretroviral therapy still regrettably limited to the developed world, palliative care for HIV/AIDS remains an important element of AIDS care worldwide, and will continue to be relevant even as the benefits of therapy are extended to the millions of people worldwide who urgently need it

All of these trends lead to the conclusion that there is an important and ongoing need for effective and expert palliative care interventions for the care of patients with HIV/AIDS in both the developed and developing world, and that the goal of comprehensive AIDS care must be to integrate palliative and disease-specific therapy on both individual and programmatic levels, across the continuum of disease, including but by no means limited to the end-of-life and late-stage disease (19). In many ways, in fact, AIDS in the HAART era has become less of a rapidly and uniformly fatal disease (similar to an aggressive and untreatable cancer), and more of a chronic, progressive illnesses [similar to congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), etc.], with all of the challenges that are posed in palliative care practice for conditions for which the prognosis and clinical course can be quite variable (19, 20).

Pain and Symptom Management

Since early in the epidemic, patients with AIDS have been documented to have a high prevalence of pain and other symptoms (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35). Pain in AIDS has been believed to be a result of one or more of the following major categories:

AIDS-related opportunistic infections (e.g., cryptococcal meningitis, invasive herpes or measles virus (MV) infections, esophageal candidiasis)

HIV-related neurotoxicity (e.g., distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSP), mononeuritis multiplex)

Medication toxicity (e.g., dideoxynucleoside peripheral neuropathy, didanosine-induced pancreatitis, zidovudine-induced headache)

Coexisting painful conditions (e.g., musculoskeletal pain, trauma, and other sequelae of injection drug use) and

Other nonspecific entities (e.g., the observed association between HIV infection and headache)

(See Table 75.1 for a summary of common pain-producing infections and neoplasms in patients with AIDS, and Table 75.2 for a summary of the types of pain that may be associated with the use of antiretroviral and other HIV-related therapies.) As is true in other conditions in addition to AIDS, the most effective treatment for AIDS-related pain may sometimes be disease specific [e.g., anti-CMV therapy for cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis or colitis], sometimes more nonspecific (e.g., opioids and adjuvants for the neuropathic pain of DSP), and sometimes both (e.g., fluconazole plus a mucositis “cocktail” for odynophagia caused by esophageal candidiasis).

Table 75.1 Pain-Producing Infections and Neoplasms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 75.2 Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Related Therapeutic Agents that May Cause Paina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pain management in patients with HIV/AIDS should follow the same basic principles as in other patient populations, with several important qualifications:

Pain in patients with AIDS tends to be underdiagnosed and undertreated (23, 36, 37, and most HIV care tends to be provided within a disease-specific framework (i.e., identifying a specific opportunistic infection and treating it), in which the focus on pain per se is minimal or secondary to the emphasis on diagnosing and treating specific HIV-related complications. As a result, patients are at risk for undertreatment of pain unless this is specifically addressed by clinicians capable of responding effectively.

Table 75.3 Spectrum of Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors Occurring During Treatment With Narcotic Analgesics

LESS SUGGESTIVE OF ADDICTION

Aggressive complaining about the need for more drugs

Drug hoarding during periods of reduced symptoms

Requesting specific drugs

Openly acquiring similar drugs from other medical sources

Occasional unsanctioned does escalation or other noncompliance

Unapproved use of the drug to treat another symptom

Reporting psychic effects not intended by the clinician

Resistance to change in therapy associated with tolerable adverse effects

Intense expressions of anxiety about recurrent symptoms

Concept of “pseudo addiction”

MORE SUGGESTIVE OF ADDICTION

Reports of “lost” or “stolen” prescriptions

Selling prescription drugs

Prescription forgery

Stealing drugs from others

Injecting oral formulations

Obtaining prescription drugs from nonmedical sources

Concurrent abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs

Repeated dose escalations or similar noncompliance despite multiple warnings

Repeated visits to other clinicians or emergency rooms without informing the prescriber

Drug-related deterioration in function at work, in the family, or socially

Repeated resistance to changes in therapy despite evidence of adverse drug effects

Passik SD, Portenoy RK. Substance abuse issues in palliative care. In: Berger A, ed. Principles and practice of supportive oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1998:513–529.

Frequently, there is also a reluctance among physicians to prescribe opioid analgesics to drug-using patients, which is problematic given the high prevalence of current or prior substance use among injecting drug-using patients with HIV/AIDS (38, 39). In effect, this means in practice

that a history of substance use is also a risk factor for untreated or undertreated pain. Physicians have a professional obligation to diagnose and treat pain in patients with AIDS and substance use disorders, although this will require attention to their need for substance abuse treatment as well, if necessary, in collaboration with addiction medicine specialists. Palliative care physicians are also particularly well situated to help manage the complex interplay of pain, psychosocial issues, and concerns about addiction in patients with advanced diseases.

There is a wide range of common neuropathic pain syndromes in patients with AIDS (40, 41, 42, 43, 44, and these have increased in prevalence with longer survival because of HAART—another example of the ways in which the benefits of antiretroviral therapy have sometimes led inadvertently to new clinical challenges in palliative care and pain management (45). Moreover, some of the same medications which have helped prolong life as part of basic antiretroviral regimens (e.g., didanosine, stavudine, zalcitabine) can themselves cause peripheral neuropathy, which can further complicate regimen choice and the balance between disease-modifying and palliative agendas.

Some of the medications used in treating HIV/AIDS and related conditions (e.g., non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, rifamycins) can potentially be involved in pharmacokinetic interactions with opioids, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and other medications used in pain management and palliative care, given their metabolism through the hepatic cytochrome P-450 enzyme system (46, 47).

As a result of these and other related issues which pertain to the balance and coordination of palliative and disease-specific care, the management of pain in patients with AIDS is perhaps even more challenging and complex than in the pre-HAART era, which highlights the importance of expert palliative care input into the total care of this patient population.

Table 75.4 Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-Associated Neuropathies | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pain in Substance Users

Studies have suggested that chronic opioid addicts, including patients on chronic methadone maintenance, may have a lower threshold for painful stimuli than comparison groups (48, 49). In addition, the phenomenon of pharmacologic tolerance suggests that when narcotic analgesics are used in opioid dependent patients, they may need higher doses, which may sometimes need to be given at even more frequent intervals, than in non–opioid-dependent individuals (50). (Unfortunately, this is not the first response of most clinicians outside of palliative care settings, and indeed many clinicians’ ambivalence or discomfort about prescribing opioids to substance abusers often leads predictably to underdosing, which may lead to acting out or drug-seeking behavior by the patient, which reinforces the negative stereotypes harbored by the provider, etc.) Lastly, there remains the possibility that these patients may in fact be more likely to misuse or manipulate their prescriptions of controlled drugs than other patient populations, so particular safeguards and systems need to be implemented to minimize the risk of abuse. Indeed, one study which compared prescription drug misuse among patients with cancer and AIDS found that the latter group was far more likely to have misused prescribed analgesics, obtained analgesic medication from friends or on the street, and so on, demonstrating that one cannot treat pain effectively without also addressing the underlying drug use behaviors in this population (51). Another study has suggested a framework for assessing the likelihood of drug abuse–related behaviors concerning the use of narcotic analgesics in patients at risk for substance abuse, which can assist clinicians in identifying

high risk patients (Table 75.3) (52). Another study suggests a screening tool to help identify patients at risk for opioid prescription misuse (53).

high risk patients (Table 75.3) (52). Another study suggests a screening tool to help identify patients at risk for opioid prescription misuse (53).

Commonly effective safeguards to help prevent prescription drug misuse include the following (54, 55, 56).:

Setting clear limits on the amount and frequency of controlled drug prescriptions

Limiting the prescribing clinician to one person whenever possible

Establishing a clear and consistent policy that “lost” or “stolen” prescriptions will not be replaced

Dispensing only small amounts of medication in cases when abuse is suspected to be a risk

Enlisting responsible family members or other caregivers to help manage controlled drug supplies

Using less “tempting” alternatives whenever possible (e.g., high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)s, liberal use of adjuvants for neuropathic pain, weak opioids, or tramadol when feasible, etc.) and

Having clear contingency planning or contracting for the consequences of patients’ misuse of prescribed medications, which may be stipulated in advance with the patient, and which may include the possibility that the prescriber will decline to continue to prescribe this medication if the patient shows evidence of abusing the agreement between them (57). [See Ref. (57)] for discussion of opioid contracts.)

Making full use of the multi-disciplinary team, facilitate communication and information sharing about problematic patient behaviors to prevent staff “splitting,” and provide mutual support in working with these sometimes challenging patients

Consulting effectively with addictionologists and other substance abuse treatment professionals as part of the palliative care/pain management team. It should also be recognized that for patients on methadone maintenance, their single daily dose of methadone provides no analgesic effect, and they require additional short- or long-acting narcotics in the event that strong analgesia is needed. Their underlying tolerance to opioids also requires that they receive higher and more frequent dosing than would normally be initiated in opioid-naive patients. Theoretically, one could argue from a pharmacotherapeutic standpoint that such patients might be treated both for their opioid dependence and their chronic pain needs by the use of increasing methadone dosing given on a thrice daily schedule as opposed to maintaining their ongoing daily methadone dose and supplementing this with additional short or long-acting narcotics (58). Although this option may be available in some settings, the regulatory and programmatic guidelines which govern the operation of methadone maintenance treatment programs frequently preclude this possibility (54, 59). (One exception or special circumstance may occur at the end of life, when patients are largely home- or bedbound, and if their pain requirements are such that they need a continuous subcutaneous opioid infusion, the total daily opioid requirement including the underlying standing daily methadone dose can be converted to a single opioid for continuous infusion, which can then be managed like any other such system in patients with severe pain and advanced disease.)

In addition to pain management and drug interactions (the latter is discussed in more detail in the following text), it should be noted that there are important ways in which methadone maintenance and HIV treatment overlap in the clinical context. Given the high prevalence of HIV infection among drug users, methadone maintenance programs have long been identified as important sites for providing care to drug users with or at risk for HIV. Successful examples exist of different models for combining HIV care and drug abuse treatment within methadone maintenance programs (60, 61, 62, 63, 64, as well as coordination with palliative care services for patients with late-stage disease or complicated pain management (65). Lastly, recent studies also suggest the potential importance of buprenorphine maintenance as a comparable substitution therapy to methadone, with the advantage that buprenorphine may be prescribed in primary care settings outside of drug treatment programs (66, 67, and with the added benefit that it may be less likely to cause significant drug–drug interactions through the cytochrome P-450 system (68). Regardless of the drug treatment modality, palliative care clinicians need to work closely with HIV specialists and addictionologists in order to provide effective care to HIV-infected drug users with multiple medical and psychosocial comorbidities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree