Cancer is a feared diagnosis at any age and, for the older patient, it can present a greater challenge and options for cure may be more limited. Traditional cancer care is typically focused on the disease process: reducing tumor burden and achieving remission. However, when patients are asked what kind of care they want if serious and life-threatening disease occurs, their preferences include pain and symptom control, avoidance of prolongation of the dying process, a sense of control, concern for the burden they may place on family, and an opportunity to strengthen relationships with loved ones.

Palliative care addresses these issues and is an invaluable asset in the management of the older cancer patient. Much like the discipline of geriatric medicine, the palliative approach is interdisciplinary and addresses issues that arise in physical, psychological, social and spiritual domains. Unfortunately, many health care providers believe that palliative care and hospice are only indicated when the patient is in the final stage of their illness and near death. This limited view of palliative care and hospice is commonplace and does not address their potential usefulness and benefit in the care of the older cancer patient.

This chapter will provide an introduction to palliative care and hospice for the older cancer patient. Special attention will be paid to common issues that arise for these patients including pain and nonpain symptom management, as well as the Medicare Hospice Benefit, determining prognosis, and advance directives.

Palliative Care and Hospice

The terms palliative care and hospice are not synonymous but complementary. Palliative care is centered on the relief of suffering for patients with life-threatening or debilitating illness and the improvement of quality of life for patients and their families. Palliative care focuses on the needs and goals of the patient and his or her family, in addition to the tumor and its treatment. Pain control, symptom management, psychosocial needs, goals of care, and quality of life are primary endpoints. Palliative

Mrs. T. is an 85-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and mild cognitive impairment. She is a widow who lives in her own apartment two blocks away from her only child, a daughter. She is independent in her activities of daily living and her instrumental activities of daily living. At a routine doctor’s appointment, Mrs. T reports a persistent cough and mild dyspnea on exertion for the past 2 months. A chest x-ray demonstrates a mass with an associated postobstructive pneumonia. Further studies are obtained and Mrs. T. is diagnosed with stage 4 non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Both the patient and her daughter are shocked by the diagnosis. Upon meeting the oncologist for the first time, the daughter asks, “What are my mother’s options?”

Mrs. T. has stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer and she will not be cured. She and her daughter need to be informed that while curative treatment is not available, there may be treatments that may decrease her tumor burden, reduce her symptoms, maintain her function, and improve her quality of life. By choosing a palliative chemotherapy or referring a patient for palliative radiation, the oncologist is doing palliative care. If the oncologist or primary medical doctor needs help controlling symptoms or discussing goals of care, an inpatient or outpatient palliative medicine consultation may be available to help address these issues. For older patients with cancer, especially those with advanced disease at the time of diagnosis, palliative care should start early in the course of care.

“Hospice” can represent a philosophy of practice as well as an agency or facility that provides care for patients with end-stage disease. Hospice utilizes a comprehensive, palliative approach to care that is interdisciplinary and symptom-focused. Most older patients in the United States with advanced cancer will be eligible for the Medicare Hospice Benefit under Medicare Part A. Eligibility for Medicare Hospice benefit is determined by four criteria. First, the patient must be eligible for Medicare A. Next the patient must have a terminal condition and two physicians must certify that life expectancy is 6 months or less, given his or her prognosis. The patient must choose hospice care and the patient or agent must give informed consent. Finally, comprehensive care has to be provided by a Medicare-certified hospice. If these criteria are satisfied, all medicines, durable medical equipment, and care related to the terminal diagnosis are covered. Medicare Part B will still pay for covered benefits for any health problems that are not related to the terminal diagnosis. Patients who meet criteria for hospice benefit have to be reviewed by the interdisciplinary team and certified by the medical director or hospice physician. Benefit periods consist of two 90-day periods, followed by an unlimited number of 60-day periods if life expectancy remains at 6 months or less.

Under the Medicare Hospice Benefit, the hospice team must include a physician, nurse, bath aide, social worker, chaplain, volunteers, and possibly therapists when appropriate. Bereavement support for 1 year after a patient’s death is also included in this benefit. All medical supplies and durable medical equipment and any medication related to the terminal diagnosis and for symptom control are covered by the benefit. Most patients receive hospice services in their private home or in the nursing home setting. Although not commonplace, freestanding hospice facilities provide room and board along with care by the hospice team when the patient qualifies under “Inpatient Status,” which is typically for symptoms out of control. Most private insurance companies will also use Medicare-certified hospice criteria to enroll patients in hospice. Hospice care must provide comprehensive palliative care for terminally ill patients with a usual estimated life expectancy of 6 months or less. The care must include treatment of physical symptoms, social support, spiritual and emotional care, and bereavement care. Hospice benefits can play an important role when the patient and the physician agree that inpatient or other aggressive treatments are not in the patient’s best interest. The patient care will focus on symptom management with a switch to full palliation of symptoms and care, usually outside the inpatient hospital setting.

Hospice care can take place in different settings and the Medicare benefit provides four levels of care: routine home care, continuous home care, general inpatient care, and respite care. Routine home care is the most common level of care. Most patients receiving this level of care are in the home or nursing home setting. Patients have to be able to care for themselves at home or have appropriate caregiver support. The Medicare Hospice Benefit does not cover the cost of caregivers or nursing home room and board. All other services mentioned above are covered and the hospice must provide 24-hour on-call services. Continuous home care is for crises and for management of acute symptoms. This care can be provided in the home or in a long-term nursing home setting as well. Nursing care from 8 to 24 hours is arranged to provide intensive palliation of symptoms; such care may include titration of pain medications and the use of intravenous medications to gain control of symptoms. General inpatient care is for control of acute pain or symptoms that cannot be managed in the home or nursing home. This level of care can be provided in an inpatient hospital or freestanding hospice. Respite care is provided for caregivers that need relief or a break and is offered for up to 5 days at a time. Care can be provided 24 hours per day and includes custodial care at a hospice facility, intermediate care facility, or a hospital that contracts with the hospice.

Epidemiology

The need for palliative care among our older cancer patients will continue to grow in the coming years. There were nearly 1.5 million new cancer cases in the United States projected for 2009. One in four Americans die from cancer, and 70% of these cancer-related deaths occur in persons older than 65 years. These numbers are expected to increase dramatically with the aging of our population; also, older patients are more likely to have advanced or incurable disease at diagnosis and therefore are in greatest need of palliative care.

An ongoing challenge will be how to meet the palliative care needs of these patients. While the number of hospitals with palliative care programs has doubled over the last 10 years, the 2008 American Hospital Association Annual Survey of U.S. Hospitals reported that only 31% of hospitals have such programs. These hospitals tend to be the larger hospitals, often those affiliated with academic medical centers; large segments of the population are therefore left underserved.

Hospice agencies are more commonplace, yet referrals are often made late and their services are underutilized. Patients are dying in the hospital when they want to die at home. The median length of stay in a hospice during 2005 was 26 days; one third of patients enrolled during the last week of life and 10% on the last day of life. Hospice admissions happen late for a wide range of reasons. Most notably, it is often difficult for patients, families, and the health care team to switch out of treatment mode, give up the hope for a cure, and discuss worsening prognosis and death. In states where there is more access to palliative care services, patients are less likely to die in a hospital and are less likely to spend time in an intensive care unit or critical care unit during their last 6 months of life.

Mrs. T. is found to be a poor candidate for surgical resection due to the extent of her disease. However, she is offered radiation treatment which she accepts. She and her daughter were informed of the risks of radiation, which may include fatigue in older patients. They also were told the radiation was palliative and would not cure the cancer at this stage. Now Mrs. T. spends most of her days in bed. She has little energy and needs help with dressing and bathing. She ambulates with a walker.

Mrs. T. is found to be a poor candidate for surgical resection due to the extent of her disease. However, she is offered radiation treatment which she accepts. She and her daughter were informed of the risks of radiation, which may include fatigue in older patients. They also were told the radiation was palliative and would not cure the cancer at this stage. Now Mrs. T. spends most of her days in bed. She has little energy and needs help with dressing and bathing. She ambulates with a walker.

Determining Prognosis

(For a more comprehensive discussion on functional assessment, see Chapter 4 on “Functional Assessment.”)Determining prognosis is a challenge for most physicians. Not only must a difficult prediction be made but also, the physician must often break bad news to the patient and his or her loved ones. Almost universally, patients and their families want to maintain hope for a cure, and if that is not possible, the hope that the cancer will not progress. Elderly cancer patients may have multiple medical problems, cognitive impairment, and functional limitations at baseline. These deficits may reduce their ability to tolerate cancer treatments, increase their risk of side effects, and adversely impact their prognosis. For older patients in whom cure is not possible, the goals of care should focus on controlling symptoms and maximizing function.

The best predictor of prognosis among cancer patients is performance or functional status. Functional status refers to one’s ability to carry out his or her activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. For older patients, functional status is often impaired at baseline and may decline following interventions such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation; it may not recover. This impaired functional status may limit cancer treatment options and contribute to physical and psychological distress. Cognitive impairment is more common in older patients and, depending on the degree of the deficit, may not only reduce available treatment options but also increase the risk of delirium and worsened cognitive impairment during the course of treatment.

There are a number of different tools that have been developed to assess function. Two well-known scales are the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale rates function from 100% (normal) to 0 (dead). The ECOG rates function from 0 (normal) to 5 (dead). A median survival of 3 months roughly correlates with a Karnofsky score less than 40% or ECOG greater than 3. Typically, if a patient spends more than 50% of his or her time in bed, with progressively worsening function and an increase in other symptoms, then a prognosis of less than 3 months is likely. Newer tools are available and incorporate function, signs, and symptoms: the Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP) and the Palliative Performance Scale. These scales utilize more patient information and the added detail may help provide a more comprehensive and reliable assessment.

Discussing prognosis early in the course of care is ideal. It gives patients and their families the opportunity to consider their options and understand what to expect. Discussions should address how the patient’s concomitant medical conditions may affect the cancer course, the treatment choices, and the overall prognosis. For older patients with multiple comorbidities, poor functional status, and moderate to advanced cognitive impairment, a palliative approach may be appropriate earlier in the course of care and, for some patients, it may be indicated at the time of diagnosis. These recommendations should be shared with patients and their families, and will likely evolve over the course of care.

Mrs. T. has been undergoing radiation therapy. She arrives in your office in a wheelchair, as her shortness of breath with exertion has worsened. She also states her appetite is low and that she is constipated. She feels anxious about what is going to happen next.

Laboratory studies reveal that she is hypercalcemic; an x-ray shows progressive growth of the tumor mass.

Her hypercalcemia is treated with IV fluids and she is placed on routine medication to prevent her constipation. Discussions about future goals of care reveal she would like to continue further palliative radiation if possible, but wishes to be more comfortable.

In a discussion about advance directives, Mrs. T. states that, if she had a reversible condition, she would want it to be treated with antibiotics or other short-term treatments. If she was not going to recover, or if the risk of treatment outweighed the benefit, she would not want her life to be prolonged on machines. She fills out an advance directive stating her wishes and lists her daughter as her power of attorney in the event she cannot make decisions on her own.

Mrs. T. has been undergoing radiation therapy. She arrives in your office in a wheelchair, as her shortness of breath with exertion has worsened. She also states her appetite is low and that she is constipated. She feels anxious about what is going to happen next.

Laboratory studies reveal that she is hypercalcemic; an x-ray shows progressive growth of the tumor mass.

Her hypercalcemia is treated with IV fluids and she is placed on routine medication to prevent her constipation. Discussions about future goals of care reveal she would like to continue further palliative radiation if possible, but wishes to be more comfortable.

In a discussion about advance directives, Mrs. T. states that, if she had a reversible condition, she would want it to be treated with antibiotics or other short-term treatments. If she was not going to recover, or if the risk of treatment outweighed the benefit, she would not want her life to be prolonged on machines. She fills out an advance directive stating her wishes and lists her daughter as her power of attorney in the event she cannot make decisions on her own.

Advance Directives

An advance directive is a legal document by which patients specify their treatment preferences, goals of care, and an alternate decision maker or agent if they are unable to make their own decisions. A living will is a legal, written document that outlines a patient’s treatment preferences if and when there is a time that he or she is unable to communicate them. A durable power of attorney (DPOA) is a commonly used document by which patients appoint an agent to be their decision maker or healthcare proxy if they lose the capacity to make decisions. A DPOA is useful in that it ensures a flexible form of decision making, since the agent can respond to unanticipated problems that a written document may not predict. Advance directives are state-specific and patients must complete the form from their own state to ensure that their wishes will be carried out. It is very important that an advance directive is completed for the older cancer patient. If a patient chooses to list a DPOA, it should be a person who will respect and follow the patient’s wishes.

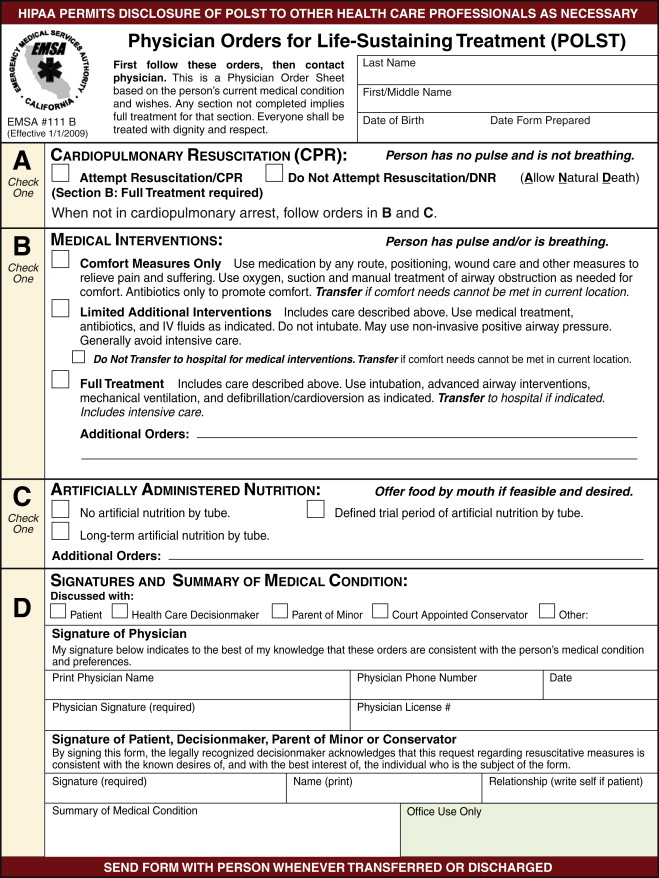

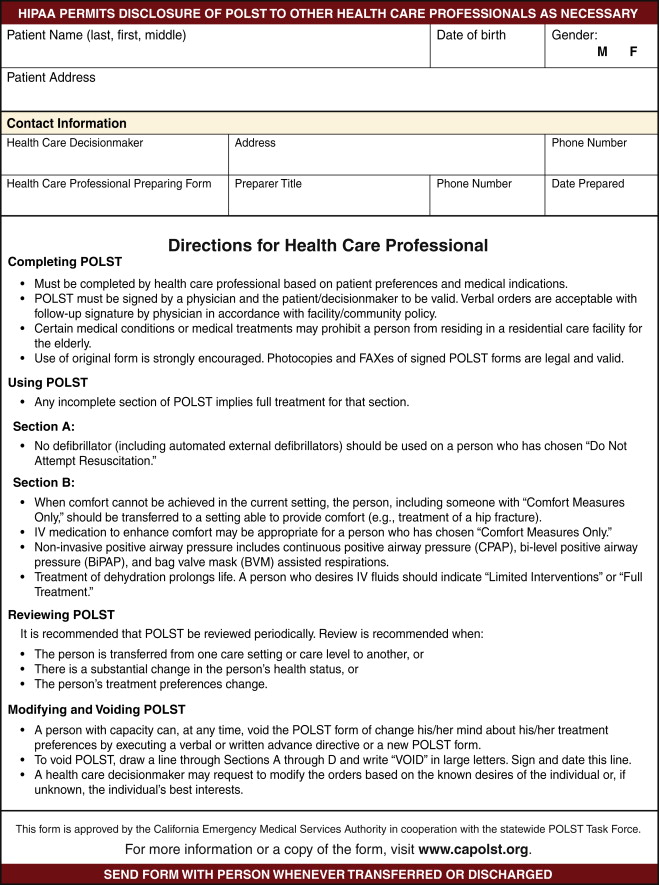

The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm program is designed to improve the quality of care people receive at the end of life. The POLST is a new form that has been implemented in some states, including California and Oregon ( Figure 28-1 ). The POLST outlines the patient’s treatment preferences and underlying medical condition and must be completed and signed by the patient or health care proxy and by his or her physician. The POLST specifically documents preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation, medical interventions, and artificial nutrition. The premise for the POLST is effective communication of patient wishes, documentation of medical orders on a brightly colored form, and a promise by health care professionals, including emergency medical personnel, to honor these wishes.

Symptom Management

Pain

(For a more detailed discussion of the evaluation and management of pain, see Chapter 17 entitled, “Pain.”)

Pain is prevalent among older cancer patients, yet it often goes undiagnosed and undertreated. Research has shown that as many as 80% of older persons diagnosed with cancer experience pain during the course of their illness. Pain control is critical, as uncontrolled pain may affect quality of life, diminish hope, increase depression, and contribute to disordered sleep, appetite disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction.

There are numerous challenges to optimal pain evaluation and management in older cancer patients. Persistent pain is epidemic among older adults and is most commonly associated with musculoskeletal disorders such as degenerative spine conditions and arthritis. Other prevalent pain conditions include peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, nighttime leg cramps, and claudication. These conditions may cloud the picture of new or worsening cancer-related pain and impede its treatment. Patients and their families are often hesitant to use opioids due to the potential for adverse drug reactions and addiction. Physicians and other health care practitioners have similar concerns and, typically, receive minimal training in pain management. These factors contribute to the reluctance among physicians to prescribe opioid medications to older patients. These concerns have been augmented by increased attention in the media on the potential for abuse and overdose. While barriers exist, pain management is essential for optimizing function and improving quality of life.

The first step in pain management is assessment. Unfortunately, many older patients and health care professionals expect pain to be a normal part of aging. Patients do not think to report their pain, or they try to bear it and accept it. Other patients may think that their physician is too busy and do not want to be viewed as a “bad patient” with another complaint. Physicians may be focused on the management of the cancer and complaints of pain and other symptoms may get deferred. The best place to begin a pain assessment is to ask, “Are you in pain?” This question has been validated in patients who are cognitively intact as well as those with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. A variety of assessment tools are available including pain scales, the pain thermometer and the faces scale as well as more comprehensive tools.

Pain management is an integral part of palliative care. A wide range of pharmacologic agents are available to manage pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be effective for bony pain from bone cancer and metastases; however, they must be used with discretion in older patients because of their potential side effects including elevated blood pressure, renal insufficiency, dyspepsia, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. NSAIDs are best used for short periods of time, and the concomitant use of an antacid agent or proton pump inhibitor may reduce their risk for GI side effects. For mild pain in a patient with multiple comorbidities and no contraindications, acetaminophen may be useful, especially if dosed around the clock. For older patients with moderate to severe pain, stronger agents such as tramadol and opioid agents such as morphine, oxycodone, or hydromorphone will be required, and dosing will likely need to be around the clock with as-needed dosing for breakthrough pain. Adjuvant agents offer synergy in pain control and address specific types of pain. Antidepressants and antiepileptics for neuropathic pain, corticosteroids for inflammation, and bisphosphonates for bone pain have been shown to be effective. Additionally nonpharmacologic approaches such as radiation treatment, acupuncture, massage, TENS units, and other types of therapy may be useful additions to a pain management plan. For pain that is difficult to control, a palliative medicine consult or pain management consult may be needed.

Mrs. T. is continuing with her radiation. She was placed on low-dose morphine for her shortness of breath and is using oxygen as needed. She feels she is able to be more active and get out of the house with assistance in her wheelchair. Her constipation is controlled with around-the-clock anticonstipation medication and her appetite is stable. Despite feeling better, her weight continues to drop and her CT scans show the cancer is progressing.

Constipation

Constipation is a common problem in the elderly and may be more severe near the end of life. Multiple factors contribute to this, such as opioid use, immobility, and dehydration due to poor oral intake. Patients need to be evaluated for treatable causes such as medications or electrolyte abnormalities. Associated abdominal pain may contribute to other problems such as anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Constipation can be controlled and the goal is to keep stool moving and avoid impaction.

Table 28-1 lists some common laxatives that can be useful in treating constipation. Docusate sodium and other stool softeners often are not strong enough alone to treat cases of severe constipation. They need to be used in combination with stimulant laxatives. Fiber products may have to be discontinued, especially if a patient’s fluid intake is poor, as these products may contribute to more impaction. When opioids are started, a laxative should always be given routinely to prevent constipation. The patient needs to be monitored for worsening symptoms. Stimulant laxatives such as senna, cascara, and bisacodyl can be used on a routine basis to keep bowel movements regular and patients comfortable. Side effects, however, may be abdominal cramping, and bloating. Saline laxatives such as magnesium hydroxide and magnesium citrate often work faster; however, caution should be taken in patients at risk for electrolyte depletion and dehydration. These can be harsher on the gastrointestinal tract. Osmotic laxatives may be easier to tolerate but side effects can include pain and bloating. Polyethylene glycol can be used for constipation, mixed in water or juice. Methylnaltrexone is a newer agent approved for subcutaneous injection for opioid-induced constipation. It has been used in patients receiving palliative care who have been unresponsive to laxatives. It is a selective mu-receptor blocker. It will not reverse the pain control of opioids and does not cross the blood-brain barrier. It is, however, contraindicated for patients in whom there is suspicion of gastrointestinal obstruction. Also, it has only been tested for short-term use. Patients should always be assessed for fecal impaction. Suppositories or enemas must be used in patients who have poor rectal tone or who are too weak to assist in defecation. Also, in cases of severe fecal impaction, trained staff must manually disimpact the rectum prior to starting any laxative treatment. Patients should be routinely monitored and reassessed for symptoms, as adjustments in medication may need to be made.

| Drug | Mechanism | Dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docusate sodium | Softener | 100-250 mg bid | Often minimally effective used alone |

| Senna | Stimulants | 187-1496 mg bid | Can cause cramps |

| Cascara | 325 mg qd | ||

| Bisacodyl | 5-20 mg po or pr qd | ||

| Magnesium hydroxide | Saline laxative | 15-40 mL po qd-bid | Diarrhea, electrolyte abnormalities |

| Magnesium citrate | 120-240 mg qd | ||

| Sodium phosphate | 20-30 mL po or pr | ||

| Lactulose | Osmotic | 5-40 mL po qd-bid | Pain and bloating, diarrhea, dehydration |

| Sorbitol | 15-30 mL po qd-bid | ||

| Polyethylene glycol | 17-36 mg po qd-bid | ||

| Psyllium | Bulk-forming | 1-2 tablespoons qd | Need adequate fluid intake |

| Methylcellulose | 1-2 mg qd | Need adequate fluid intake | |

| Methylnaltrexone bromide | Selective mu-receptor blocker | 8-12 mg SQ QOD | NOT for bowel obstruction |

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting is a common problem. Multiple etiologies such as underlying diseases other than cancer, the cancer itself, medications, or severe constipation can all add to the symptoms. First, the underlying cause must be determined so that the appropriate treatment can be provided. Causes of nausea can be broken down into four categories: central nervous system (CNS), gastric obstruction or ileus, medication side effect, or metabolic abnormalities. Patients may also have other contributing factors. Once the main cause is determined, appropriate treatment can begin. The oral route is preferred; however for those with intractable symptoms, rectal or parenteral routes are an option ( Table 28-2 ). Dopaminergic agents such as prochlorperazine and promethazine can be used orally, rectally, or intramuscularly. These agents are often useful for treating drug-induced nausea and vomiting. The side effects of these antiemetics include drowsiness and extrapyramidal symptoms. Despite these potential side effects in the elderly, these medications can be very helpful and short-term use may benefit patients by controlling symptoms and improving quality of life. For CNS causes of nausea and vomiting, haloperidol or droperidol can be helpful. Patients who are at risk for increased intracranial pressure may be started on corticosteroids and these may concomitantly improve their symptoms of nausea and vomiting. For patients with significant bowel disease, corticosteroids can relieve bowel edema and improve nausea. High doses of corticosteroids should be used with caution in the elderly as they can lead to gastric irritation, delirium, and fluid retention. Serotonin-receptor blockers are often helpful in cases of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Anticholinergics and antihistamines can be useful, especially in cases of vestibular nausea and central nervous system disease. However, care should be taken with these agents, as anticholinergic side effects such as dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, blurry vision, and confusion can be difficult for elderly patients to tolerate. Benzodiazepines are often helpful and may help relieve nausea, especially if the nausea is related to anxiety. Patients must be continually reassessed for the underlying cause of nausea and vomiting; they should use these medications on an as-needed basis.

| Drug | Mechanism | Dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prochlorperazine | Dopamine antagonist | 5-20 mg PO/IM/IV q4-6h, 25 mg PR q 8-12h | EPS side effects |

| Promethazine | Dopamine antagonist | 25 mg PO/PR q4-6h | EPS side effects |

| Droperidol | Dopamine antagonist | 2.5-5 mg IM/IV q4-6h | EPS side effects |

| Haloperidol | Dopamine antagonist | 0.5-5 mg PO/IV/IM/SC q4-6h | EPS side effects |

| Metoclopramide | Dopamine antagonist | 5-20 mg PO/IM/IV/SC q6h | EPS side effects |

| Ondansetron | Serotonin receptor blocker | 8 mg PO/IV/SC q8h | Chemotherapy-induced nausea |

| Granisetron | Serotonin receptor blocker | 0.5-1 mg PO/IV/SC q12h | Chemotherapy-induced nausea |

| Diphenhydramine | Antihistamines | 25 mg PO/IV/IM q4h | For vestibular symptoms |

| Meclizine | Antihistamines | 25-50 mg PO q4-6h | For vestibular symptoms |

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | 1-4 mg PO/IV q6h | For chemotherapy induced nausea, or increased intracranial pressure |

| Prednisone | Corticosteroid | 5-20 PO q4h | For chemotherapy induced nausea, or increased intracranial pressure |

| Scopolamine | Anticholinergic | 1.5 mg patch q72h | Delirium risk |

| Hyoscyamine | Anticholinergic | 0.125 mg tid | Delirium risk |

| Dronabinol | Cannabinoid | 2.5-7.5 mg PO bid-tid | Chemotherapy-induced nausea |

| Lorazepam | Benzodiazepine | 0.5-2 mg PO/SC/IM q4h | For reducing anxiety, nausea |

| Diazepam | Benzodiazepine | 5-10 mg q4h | For reducing anxiety, nausea |

Dyspnea

Dyspnea can be a debilitating symptom for many patients. Causes may include the underlying cancer or progression of illness and terminal condition. Patients may have an uncomfortable awareness of breathing, rapid breathing, or air hunger. Dyspnea can be significantly uncomfortable for patients, and their families may be distressed by the patient’s fluctuating respiratory rate, by hearing increased secretions, and by the gurgling sound or “death rattle” that often is heard when a patient is nearing death. It is important to assure patients that the relief of these symptoms and overall comfort is the goal of care ( Table 28-3 ). Often, other treatments must be reassessed for appropriateness; these should be discussed with the patient, the family and the physician. Interventions such as antibiotics for acute infection and diuretics for fluid overload can be considered based on the patient’s preference and the stage of the disease process.

| Class of Drug | Examples | Dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shortness of Breath | |||

| Oxygen | 2-10 L/min by nasal cannula | Use for patient comfort, shortness of breath | |

| Opioids | Morphine | 5-15 mL PO/SL/PR | Decrease patient perception of breathlessness; titrate up to patient comfort |

| Methadone | |||

| Oxycodone | |||

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam | 1-2 mg PO/SL | Can help with anxiety and breathlessness |

| Diazepam | 2.5-10 mg PO/SL | ||

| Secretions | |||

| Scopolamine patch | 1-3 patches q1-2 days | In alert patient, may cause dizziness and dry mouth | |

| Hyoscyamine | 0.125 mg PO q4-6h | Less sedation than scopolamine | |

| Glycopyrrolate | 0.2-1 mg PO q4-6h | Least sedation and fewer CNS side effects | |

| Atropine drops | 2-4 drops PO/SL q2-4h | Can be used when patient is unable to swallow and as needed | |

As the body starts to shut down, renal function decreases, the circulatory system slows, and patients are at higher risk for fluid overload. Treatment with intravenous fluids may make symptoms of shortness of breath worse. Also, tube feedings may have to be slowed or discontinued, as the patient may be at higher risk of fluid overload and aspiration. Patients should be allowed to eat as they can tolerate; however, food consistency may have to be changed if they are having more difficulty chewing or swallowing. Patients who are too lethargic to eat should not be forced, as aspiration is a high risk and can make the breathing even more labored.

Oxygen is used to improve patient’s symptoms and can be used easily. Patient’s life expectancy will not be prolonged by the use of oxygen; however, the patient may have less air hunger and may have the sensation of breathing easier. Opioids are the main pharmacologic agents for treating dyspnea. Morphine sulfate can be used orally, sublingually, intravenously or rectally. Doses can begin very low, starting at 5 to 10 mg every 2 to 4 hours. However, it should be titrated up at least by 30% to 50% until symptoms are controlled. Patients can be placed on continuous long-acting doses of the opioid preparation, but short-acting opioid formula should still be available for severe symptom control as needed. Titration should be based on the patient’s symptoms, not on his or her respiratory rate. Studies on nebulized morphine and hydromorphone have shown variable results. The benefit over enteral narcotics is still unclear and more research is needed.

Benzodiazepines can also be effective in treatment of dyspnea. Patient may feel symptomatic relief as well as less anxiety and air hunger when symptoms are more severe. Benzodiazepines may need to be used around the clock and may need to be titrated based on the patients symptoms. Nonpharmacologic methods to help reduce shortness of breath include placing the patient in a more open room, using air from a fan, keeping the patient in an upright position, relaxation techniques, and support for the patients spiritual or psychological needs.

Dyspnea at the end of life is often caused by secretions and difficulty with swallowing. Many patients have recurrent aspiration. If a patient is still eating, the benefit of quality of life versus the risk of aspiration must be considered. Many patients are willing to take some risk for the benefit of being able to enjoy food. Many patients may be more uncomfortable due to increased secretions from fluid overload, aspiration, infections, and inability to control secretions. Often medication to help dry secretions can be beneficial. Scopolamine patches can be used and are helpful in drying secretions. Side effects include dizziness, blurred vision, and oral dryness. Hyoscyamine is less sedating than scopolamine and can be used orally when the patient can still swallow. Glycopyrrolate has fewer CNS side effects and can be used orally and intravenously. It does not cause as much drowsiness compared to the others and the risk for delirium is low. This is often a safer alternative in the elderly patient who still is awake and at high risk for delirium. In patients who cannot swallow and who are mostly unconscious, atropine drops can be used orally or sublingually. These can be used to dry oral secretions and help reduce the gurgling from the throat often heard when a patient is nearing death and has no control over secretions, sometimes referred to as the “death rattle.” Medications to help control secretions are listed in Table 28-3 . Often, patients’ caregivers can be trained to help clear secretions by using swabs to clear out the oropharynx, suctioning gently with a bulb syringe, and making postural changes to clear the airway.

Depression

(For more comprehensive discussion and treatments, see Chapter 16 on “Depression.”)

Depression is a common problem among elderly cancer patients. A recent systematic review found that approximately 15% of palliative care inpatients suffer from major depression and that the prevalence of all depressive disorders including minor depression, dysthymia, and depressive adjustment disorders is likely to be twice this value. Unfortunately, depression is often overshadowed by other physical complaints. Depression is reported less often than pain and fatigue when patients are asked about common symptoms. It can be especially confusing with cancer patients, because many of the biological symptoms of depression are expected consequences of cancer and its treatment such as fatigue, sleeplessness, change in weight, and loss of appetite. Other indicators of depression in the terminally ill are suicidal ideation and feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, and guilt. Anxiety often coexists with depression and may be an associated symptom. Older cancer patients facing death may experience a depressed mood; it can be difficult to differentiate when depressed mood or normal grief becomes clinical depression. These distinctions are important, as depression significantly impacts functional status and quality of life.

Given these complexities, what is the best way to identify depression in elderly cancer patients? The short answer is to ask the patient. Research has shown that patient interviews are superior to self-report and visual analogue scales for the identification of depression, and a diagnostic interview is the gold standard. Certainly, the ideal tool in the clinical setting would be one that is quick, easy, and reliable. Chochinov et al. demonstrated that incorporating a single-item interview for depressed mood and asking “Are you depressed?” reliably and accurately diagnosed the presence of depressed mood. The authors also suggested that inquiry regarding loss of interest and pleasure in activities may be additive. Once identified, further questioning is required through thorough history taking and possibly the implementation of additional questionnaires such as the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Other questionnaires ask more questions and have been found to be reliable; examples include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. These may be useful and offer a more definitive diagnosis of depression rather than just the identification of depressed symptoms; however, their length and requirement for prolonged attention may make them hard to complete with frail elderly patients. While self-report and visual analog scale measures are not reliable in making the diagnosis of depression, they may be useful to quantify the severity of a depressive syndrome, once it is identified, and in monitoring change over time. Once depression is suspected in a patient, further history should be obtained and further information gathered to assess for a history of depression, its prior treatments, successes and failures; medical etiologies; or contributors such as thyroid disease, anemia, and electrolyte disturbances.

Treating depression may lead not only to an improvement in physical symptoms but also have a major impact on quality of life and, possibly, survival. Treatment may be effective even in those who are terminally ill and it carries minimal risk. A consensus panel by the American College of Physicians/American Society of Internal Medicine reported that psychotherapeutic interventions have been shown to be effective in relieving depressive symptoms, improving quality of life, and prolonging life, while psychopharmacologic treatments may relieve depressive symptoms and alleviate psychological distress in a majority of patients. Simultaneous symptom management, especially pain control, is essential, as poorly controlled pain is a risk factor for depression. Additional nonpharmacologic interventions are also important including psychological support, spiritual support, and symptom management. Talking through concerns, answering questions, and reassuring the patient that his or her pain will be relieved are all important. This type of support can be provided in the context of an office visit or visit to the infusion center by staff and by the interdisciplinary team if hospice is involved. A palliative care approach will help ensure that comprehensive care is provided.

There are many available antidepressants; it may seem difficult to choose the right one for an older patient with advanced cancer. The risk/benefit ratio is low with treatment and there is little reason not to consider a trial of intervention. Important considerations include: good side effect profile, little or no interaction with other drugs used in palliative care, additional benefits (e.g., helpful with neuropathic pain or somnolence), quick onset of action, and safe in liver or renal failure. Citalopram and sertraline are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that have been shown to be effective and well tolerated in palliative care patients. These agents are preferred, as they have few active metabolites to accumulate and cause toxicity when compared with fluoxetine. Mirtazepine, a noradrenaline and specific serotonin antagonist (NaSSA), is particularly useful in patients with insomnia, poor appetite, nausea, and anxiety. Duloxetine may be a good choice in patients with concomitant neuropathic pain. Venlafaxine may be useful for patients not responsive to the SSRIs. Antidepressants typically require a 4-week trial period to determine effectiveness. If one agent has not been effective, then try switching to a different agent. If there is still no improvement, or if additional symptoms such as paranoia, delusions or active suicidal ideation are present, then the involvement of a psychiatrist is recommended.

Depression routinely goes unaddressed in the older cancer patient. Physicians may not recognize depression in their patients and often lack the knowledge and skills to identify depression. Patients, their families, and health care providers believe that psychological distress is a normal feature of the dying process and fail to differentiate natural, existential distress from clinical depression. Other barriers exist including the stigma of depression, a lack of time to address the issue during clinical encounters, the concern that talking about depression will cause further distress, and physician reluctance to prescribe psychotropic agents. Optimal care for the older cancer patient requires that depression be looked for and treated.

Anxiety and Agitation

Anxiety and agitation are common near the end of life and may be more difficult to control than other symptoms. Terminal restlessness can be assessed and treated to improve the patient’s life. Patients may have multiple factors adding to agitation such as disease process, electrolyte abnormalities, shortness of breath, uncontrolled pain, medication side effects, or psychological fear and depression. Intervention goals are to provide patients with comfort and the best-possible quality of life. Patients with advanced cancer who have anxiety are more likely to have difficulties in the physician-patient relationship. In the elderly, depression, delirium and the possibility of cognitive dysfunction can make evaluation and treatment more complex.

As for depression, anxiety can present in many ways. Poor symptom management can add to more anxiety. Patients should be assessed for uncontrolled pain, shortness of breath, constipation, and nausea at every encounter. Poor sleep can also lead to anxiety. Patients may have depression with an anxiety component and appropriate medication should be started. Patients who are debilitated or who require more care may often feel anxious about becoming a burden on family or caregivers. Appropriate and early intervention to discuss care needs and possibilities for care facilities should come earlier in the course of illness. Social, spiritual, and cultural aspects also must be addressed. A patient whose death is impending may wish to reconcile with loved ones with whom he or she lost contact. Some patients may need religious or spiritual support. All these disciplines should be offered and considered in a patient who seems to be more anxious. Medication can often help in patients who are still undergoing active care and even for those on hospice care. SSRIs are common antidepressants that can help with anxiety, as well as with depression. Anxiolytics, such as benzodiazepines, can often be used in acute anxiety. Caution should be taken in the elderly, as the side effects of benzodiazepines can include confusion and agitation. They are not recommended for long-term use for chronic anxiety in the elderly. For those who are near the end of life, they can be used more acutely. During the dying process, when some patients may suffer from terminal delirium and agitation, around-the-clock benzodiazepines and, often, antiseizure medications can be used for sedation. Antipsychotics, especially atypical antipsychotics, are often used and can be helpful in acute anxiety or agitated state, particularly in patients with underlying cognitive impairment. Mood disorders and underlying psychiatric disorders should be assessed and treated. Patients may also benefit from psychological support, spiritual support, and social support. Anxiety often stems from patient’s fears of pain and suffering. There is a high association of depression and anxiety in patients with chronic medical problems, as is the case for many elderly. The addition of a cancer diagnosis will often exacerbate the condition. Use of interdisciplinary team members, spiritual support, family involvement, and psychiatric and psychological support should be instituted early.

Delirium

Delirium is also highly prevalent at the end of life and in acute illness. Delirium is defined as an acute state of disturbed consciousness. Usually, it is abrupt in onset and associated with fluctuating symptoms. Patients may be lucid at intervals then decline again. These symptoms can be treated and it is often reversible. Patients who are over 65 years old are at the highest risk for delirium. Delirium can increase length of hospital stay in older patients and can increase mortality. Delirium in cancer can be a challenging diagnosis. It can represent a reversible condition, new disease in the brain, or an irreversible part of the evolution of the terminal disease. Distinguishing delirium from dementia can often be difficult, especially in patients with a history of dementia. In delirium, confusion occurs acutely and is associated with altered consciousness. Dementia is usually a slow and progressive cognitive loss. When delirium is superimposed on a patient with dementia, diagnosis can be difficult.

As delirium can be a reversible condition, it is important to evaluate the cause and to treat it if possible ( Table 28-4 ). One of the main causes of delirium is drug toxicity. Medications to treat acute illness such as antibiotics, centrally acting antihypertensives, and steroids are common in the acute-care setting. In addition, medications used for palliation of symptoms including opioids, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and antiseizure drugs can all cause delirium, especially in older patients. Metabolic abnormalities and endocrine disorders as well as acute fever, hypotension, and infection are all risks for confusion. Patients with cancer are highly susceptible to delirium from the disease itself or due to consequences of the cancer treatment. Hematologic abnormalities and neurologic causes including new cerebral vascular event, infection, head trauma, seizures, or bleeding should be considered. Toxic effects of antineoplastic treatments and new CNS tumor to the brain and meninges can cause acute changes in consciousness. In elderly patients, underlying psychiatric disorders such as dementia can make delirium more pronounced and difficult to diagnose. Patients with depression, anxiety, or agitation can present with confusion as the main symptoms. Alcohol, drug, or medication withdrawal can add to delirium. In an elderly patient, environmental changes such as sleep deprivation, inability to communicate because of hearing loss, vision loss, and change in environment can increase the confusional state.