Outline

Quality of Life in Gynecologic Cancers

Management of Common Physical Symptoms

Psychosocial and Spiritual Needs of Patients and Families

Management of Psychosocial and Spiritual Distress

Quality of Life Issues in Advanced and Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

Quality of Life Issues in Advanced and Recurrent Uterine and Cervical Cancer

Key Points

- 1.

Palliative care is interdisciplinary care that seeks to prevent, relieve, or reduce the symptoms of a disease without affecting a cure.

- 2.

Certain treatments may not result in improved survival but may result in decreased symptoms. Clinical trials have therefore begun measuring quality of life (QoL).

- 3.

Other QoL measures include survivorship. That is the process of helping the patient have the highest QoL after treatment.

- 4.

Often pain associated with cancer is undertreated. Other symptoms, especially psychological ones, are often ignored or not recognized.

- 5.

A multidisciplinary team is required to recognize and care for this aspect of cancer care and includes social workers, pastoral care, nutritionists, oncologists, pain specialists, psychologists, physical therapists, and caseworkers.

- 6.

Palliative care is an important emerging field in cancer care.

Evolution of Palliative Care

Once viewed as limited and focused care during the final days of life, the scope of palliative medical care and quality of life (QoL) research has evolved since the 1990s. Although several definitions of palliative care exist, it is broadly defined as interdisciplinary care that seeks to prevent, relieve, or reduce the symptoms of a disease or disorder without affecting a cure. “Palliative care” and the related term “palliative medicine” are being used with increasing frequency in the United States and have become the labels of choice throughout the world to describe programs based on the hospice philosophy. When approaching death, including care at the end of life, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends: “Palliative care should become, if not a medical specialty, at least a defined area of expertise, education and research.”

Palliative care overlaps with “terminal care,” “death and dying,” “hospice,” “end-of-life care,” “comfort care,” and “supportive care.” The term “supportive care,” which is often used by oncologists, is particularly ill defined and sometimes refers to comfort care or palliative support of critically ill patients, particularly those suffering from the adverse effects of cancer treatment. All of these terms have a number of meanings and are often unfamiliar to clinicians. They outline the relationships of health care professionals with patients and family members during the terminal stages of life and the treatment of advanced malignancies ( Table 20.1 )

|

QoL is a concern in all areas of medicine and of primary importance in the palliative care setting. Within the clinical setting, assessment of a patient’s QoL begins with an understanding of a patient’s knowledge about his or her condition and potential management strategies, his or her values, and his or her personal cost–benefit calculations. Certain therapies have no chance of improving survival endpoints but may have an acceptable therapeutic index based on a reasonable balance between the toxicity of the intervention and the resolution of symptoms secondary to the condition being treated. With this concept in mind, investigators and clinicians have begun to collectively measure QoL in clinical trials and community-based practices in an attempt to define alterations in QoL and to prospectively ascertain interventions that might improve “survivorship.” It is no longer appropriate to simply survive one’s illness; rather, one must avoid the “killing cure,” allowing patients to enjoy life and function productively while interacting with their environment during multimodality cancer treatment.

The gynecologic oncologist is in a unique position to function collectively as a primary care provider, surgeon, radiation oncologist, and chemotherapist, allowing comprehensive transfer of treatment with an emphasis on the patient’s QoL. Reports from the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Care at the End of Life and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Task Force on Cancer Care at the End of Life, both published in 1998, clearly acknowledge the physician’s responsibility in caring for patients throughout the continuum of their illness ( Table 20.2 ). The ASCO document asserts: “In addition to appropriate anti-cancer treatment, comprehensive care includes symptom control and psychosocial support during all phases of life.”

Barriers to Optimal End-of-Life Care Identified by the American Society of Clinical Oncology

|

In addition, in 2015, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology has published recommendations regarding improving the quality and cost of gynecologic oncology practice. These recommendations include prompt referral to palliative care services for advanced and recurrent gynecologic cancer patients. In addition, the recommendations discourage the use of unnecessary chemotherapy and surgery close to the end of life in these patients because research has shown an alarmingly high percentage of patients receiving these procedures within the last 6 months of life. Furthermore, multiple studies have indicated that trainees are not adequately prepared in the realm of palliative care support for gynecologic cancer patients.

Gynecologic oncologists are not only faced with the challenge of providing end-of-life care, but they must also explore ways to integrate palliative care throughout the continuum of illness. Indeed, recent literature suggests that gynecologic oncologists recognize the growing importance of their role as the patient’s disease progresses. It is in this role, when the challenges of effective, compassionate care and communication are heightened, that an understanding of the principles and the clinical practice of palliative medicine are critical. A review of the recommendations for and barriers to effective palliative and end-of-life care as outlined by the Institute of Medicine and ASCO is listed in Table 20.2 .

Palliative care is differentiated from other medical specialties by its fundamental philosophy of care delivery; care is collaboratively provided by an interdisciplinary team prompted by issues and concerns of the patient and family. “Family” as defined by the patient and staff may include friends as well as relatives. Palliative care is, by definition, care delivered through the coordinated efforts of the team that is collectively confident and skilled when assessing and addressing the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of the patient and family. It differs from more traditional “multidisciplinary” care that is directed by a physician, which allows team members to simply focus on their own areas of expertise. In contrast, the palliative care “intradisciplinary” team recognizes that all information about the patient and family is relevant. Thus, the home health aide or the pharmacist may have a point of view that would be helpful for the care plan. Common members of these multidisciplinary teams include medical social workers, pastoral care, nutritionists, radiation oncologist, medical oncologist, pain specialists, psychologists, physical therapists, and caseworkers. Early in the treatment of a gynecologic cancer, side effects of therapy should be anticipated and treated prophylactically. Later, some symptoms may be dealt with without the extensive evaluation associated with the assessment of tumor response or disease status. However, the development of symptoms often indicates disease progression, and appropriate laboratory or radiographic studies may lead to an alteration of treatment. As the cancer progresses, making cytotoxic therapy less likely to be effective, the workup of new symptoms must be tailored to the individual patient based on the prognosis as well as on the desires expressed by the patient and family. In end-of-life care, there is no room for long-term evaluation or a “wait and see” attitude. In fact, within even just 1 day of referral to palliative care services, symptom burden improves for patients. Data have indicated that the triad of younger age (<50 years), a history of pain, and depression or anxiety can perhaps capture patients that will have higher symptom burden and should perhaps be either watched carefully for palliative care needs or referred early to palliative care services. Furthermore, QoL improves, depression decreases, and the use of chemotherapy close to death is reduced when patients are introduced at least once to palliative care services during their treatment experience. As a result, control of annoying symptoms may be pursued more aggressively, and management may resemble that given in an intensive care situation but without an extensive diagnostic evaluation. Control of symptoms is not an end in itself, but it should be sought to allow the patient time to optimize QoL and to support the patient in reaching peace with self and closure with important people in the patient’s life.

Quality of Life in Gynecologic Cancers

QoL varies depending on the gynecologic cancer disease site, stage, and treatment. In ovarian cancer, for example, the majority of patients present in their 60s with advanced metastatic disease. These patients experience a decline of QoL before diagnosis. However, many respond well to treatment, which creates symptomatic improvement, easing the disease burden and therefore improving QoL. Unfortunately, most patients with advanced ovarian cancer have recurrences, and despite poor outcomes, patients are often treated with multiple rounds of chemotherapy. In contrast, patients with cervical cancer overall present at a younger age with minimal symptoms in the earlier stages of disease. However, whether it is fertility-terminating surgery or chemotherapy and radiation, the therapy can be life-altering or toxic. Despite its initial expectation of lower toxicity index, the use of targeted therapy has not yet demonstrated a significant alleviation of the adverse drug event burden as originally intended. These side effects suffered, however, may be acceptable in the event of likely cure. However, in the advanced cases, when these women have recurrences, their already low QoL, combined with new symptoms related to recurrence, makes further treatment difficult in the setting of often ineffective therapy. Furthermore, patients with cervical cancer are often of lower socioeconomic status and present with unique social and emotional challenges, especially in the setting of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care. Patients with endometrial cancer are perhaps the most favorable in terms of QoL in that they frequently present in early stage and are often treated with surgery alone. However, their medical comorbidities, including obesity and diabetes, are challenging to address in survivorship.

Quality of Life in Ovarian Cancer

Because the majority of patients with ovarian cancer present in advanced stages, most women enter treatment with some QoL dysfunction likely related to symptom severity at presentation. The study of QoL in ovarian cancer therefore must take into consideration this baseline level of dysfunction and monitor the effect of surgery or chemotherapy. Because the prognosis is generally poor for those with advanced ovarian cancer, the goal of therapy is perhaps to extend life without greatly compromising the patient’s QoL. In clinical trials, great attention is now paid to measuring QoL throughout the study of cancer therapeutics. QoL has also been monitored posttherapy to document the needs and deficiencies of these women. In the measurement of QoL, a standardized and validated measure, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Ovarian (FACT-O), is frequently used in clinical trials. The FACT-O is a combination of the FACT-G (General) plus additional questions related specifically to ovarian cancer ( Tables 20.3 and 20.4 ). The FACT-G is composed of four subscales: the physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being. Patients can answer on a scale of 0 to 4, with 0 being not at all and 4 being very much. In the physical well-being subscale, the patient is asked to elaborate on pain, nausea, and lack of energy and how these physical symptoms affect their life and how bothered by these symptoms the patient is. The social/family well-being subscale addresses the amount of emotional support the patient has from her friends, family, and partner. The emotional well-being subscale targets the patient’s feelings and emotions regarding her illness and how anxious she is about dying from this disease. Finally, the functional well-being subscale concerns the patient’s ability to function in society, such as her ability to work, sleep, and enjoy life. This subscale looks at the patient’s ability to accept illness and move on to live a “normal” life again. In the final section of the FACT-O, there is an additional concerns scale that targets specific symptoms, life-altering changes, and chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. In 2011, Donovan et al. performed a comprehensive review of the QoL literature related to ovarian cancer between the years 2000 and 2011. They sought to find the most important symptoms that should be recorded to measure QoL in ovarian cancer trials. The panel of experts identified the following “core” ovarian cancer symptoms: abdominal pain, bloating, cramping, fear of recurrence or disease progression, indigestion, sexual dysfunction, vomiting, weight gain, and weight loss. In addition, ovarian cancer–specific symptoms were suggested to be of value in the design of future QoL endpoints: abdominal pain, bloating, cramping, fear of recurrence, indigestion, sexual dysfunction, vomiting, weight gain, and weight loss.

| FACT-G | QLQ-C30 |

|---|---|

Physical Well-Being

|

|

Social/Family Well-Being

| |

Emotional Well-Being

| |

Functional Well-Being

|

| Cervical | Ovarian | Endometrial | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding or discharge | X | X | |

| Odor | X | ||

| Fear of sex | X | ||

| Sexually attractive | X | ||

| Narrow or short vagina | X | ||

| Fertility concerns | X | X | |

| Fear of harms of treatment | X | ||

| Interest in sex | X | X | |

| Body appearance | X | X | X |

| Constipation | X | X | |

| Appetite | X | ||

| Urinary incontinence, dysuria, discomfort with urination, frequency | X | X | |

| Ability to eat foods that are liked | X | ||

| Swelling in stomach | X | X | |

| Weight loss | X | ||

| Control of bowels | X | ||

| Vomiting | X | ||

| Hair loss | X | ||

| Appetite | X | ||

| Ability to get around | X | ||

| Feel like a woman | X | ||

| Stomach cramping | X | X | |

| Discomfort of pain in stomach | X | ||

| Hot flashes | X | ||

| Cold sweats | X | ||

| Fatigue | X | ||

| Pain with intercourse | X | ||

| Trouble with digestion | X | ||

| Shortness of breath | X | ||

| Discomfort or pain in pelvis | X |

Several prospective randomized trials in the United States have used the FACT-O measure to assess QoL. The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) has used the FACT-O in prospective phase III randomized trials to monitor QoL during various experimental treatment protocols ( Table 20.5 ). The first ovarian cancer GOG trial using the FACT-O was published by . They published the QoL results for a randomized trial of interval secondary cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer patients. In this trial (GOG protocol 152), 424 patients were enrolled, and 380 (90%) of these women completed the initial and midtreatment questionnaires. Roughly 80% of the patients continued to complete the measures at the second though fourth assessment points. In this study, a better QoL as measured by the FACT-O was associated with improved overall survival (OS). Although the FACT-O results did not differ between the groups receiving this surgical intervention or not, this trial did emphasize that improvements in QoL existed for women in both arms at 6 and 12 months after therapy.

| Cancer Site | GOG Protocol Number | Study Title |

|---|---|---|

| Ovarian | GOG 152 (2005) | A randomized trial of interval secondary cytoreduction in advanced ovarian carcinoma |

| GOG 172 (2007) | A randomized trial intravenous paclitaxel and cisplatin versus intravenous paclitaxel, intraperitoneal cisplatin and intraperitoneal paclitaxel in patients with optimal stage III epithelial ovarian carcinoma or primary peritoneal carcinoma | |

| GOG 218 (2013) | A randomized trial of intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without bevacizumab | |

| Cervical | GOG 169 (2006) | A randomized trial of cisplatin versus cisplatin plus paclitaxel in advanced cervical cancer |

| GOG 179 (2005) | A randomized trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in advanced carcinoma of the cervix | |

| GOG 204 | A randomized trial of paclitaxel plus cisplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus topotecan plus cisplatin in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent carcinoma of the cervix | |

| GOG 240 | A randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for advanced or recurrent cervical cancer | |

| Endometrial | GOG 122 (2007) | A randomized trial of whole abdominal irradiation and combination chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma |

| LAP-2 | A randomized clinical trial of laparoscopy (scope) versus open laparotomy (open) for the surgical resection and staging of uterine cancer |

Notably, an effective treatment regimen demonstrated for women with stage III ovarian cancer that has been optimally surgically debulked is a combination of intraperitoneal (IP) and intravenous (IV) chemotherapy. GOG 172, a phase III trial comparing IP cisplatin and paclitaxel plus IV paclitaxel with IV cisplatin and IV paclitaxel, demonstrated that the IP/IV regimen was associated with the longest median survival time (65.6 months for IP/IV vs. 49.7 months for IV) that has yet been reported in women with optimally debulked stage III ovarian cancer. This statistically significant and clinically meaningful difference between IP and IV chemotherapy prompted a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Clinical Announcement (2006) alerting the public and health professionals to the superiority of IP chemotherapy in the optimal disease setting. However, the superior survival outcomes, demonstrated with the IP regimen in GOG 172, was associated with considerable toxicity, and patients randomized to IP therapy reported significantly worse QoL before cycle 4 ( P <0.0001) and at 3 to 6 weeks after treatment ( P = 0.0035). However, there were no significant overall QoL differences between regimens 1 year posttreatment. Despite the reported benefits of IP therapy for progression-free survival (PFS) and OS, this study demonstrated physical and functional well-being deficits both during and after therapy in the IP arm. Neurotoxicity and abdominal discomfort were also more prevalent in the IP arm. Although the QoL scores improved over time, specifically at 12 months from initial treatment, this manuscript perhaps prompted physicians to reconsider this treatment modality secondary to toxicity concerns. In addition, IP is a more difficult treatment for the treatment team to administer as well as potentially more toxic. However, ultimately, the QoL differences between regimens were not significant long term. In 2015, Wright et al. looked at the use and effectiveness of IP chemotherapy in 823 women at six different institutions. These authors demonstrate a relatively poor acceptance of IP chemotherapy (<50%) despite published survival advantages. They cite certain factors as potential barriers to IP/IV chemotherapy usage including toxicities, patients’ preferences, the inconvenience of administration, potentially higher rates of extraabdominal cancer recurrences, and beliefs that other chemotherapy regimens may be comparable with fewer toxicities. This study did demonstrate improved survival advantages, but IP chemotherapy usage is associated with younger age and fewer medical comorbidities, thus perhaps explaining the less than 50% adoption of this route of treatment.

In 2009, von Gruenigan et al. combined the results from the above described trials and reported the specific line items in the FACT-O that were reported between cycles. For example, the authors report significant differences in concerns such as pain, nausea, feeling ill, and side effects of treatment. Because significant functional well-being deficits were also reported, they suggest interventions aimed at specific side effects as a means to improve patients’ functional status. Social well-being went relatively unharmed except for satisfaction with one’s sex life. Emotional deficits were also noted across all items except for acceptance of illness. This study demonstrated that when broken down into individual line items, perhaps interventions can be designed to target improvement in these various areas. In 2013, Monk et al. reported on the QoL outcomes of a randomized trial incorporating bevacizumab into the carboplatin and paclitaxel IV chemotherapy. This study included a maintenance of bevacizumab versus placebo for a total of 22 cycles (treatment given every 3 weeks). During the initial chemotherapy phase of six cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel, the patients on bevacizumab experienced significantly lower QoL scores (worse QoL) than those on chemotherapy alone. It was curious that bevacizumab compromised QoL during the chemotherapy phase only of treatment. Most striking, though, is perhaps the idea that extending PFS did not translate into enhanced QoL according to the authors. However, although QoL was not improved, the authors use the QoL data to conclude that this new regimen is an acceptable alternative to standard care.

Several European studies have also evaluated QoL in prospective trials. Although these studies use different QoL tools, it is important to comment on some of these studies in which QoL data in the United States are lacking. First, in 2010, Vergote et al. published the results of a randomized trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgical cytoreduction versus primary surgical debulking followed by chemotherapy. The QoL results were then published in 2013. Per the authors, QoL was assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Module-C30 (QLQ-C30) core questionnaire version 3, which consists of a global health status and QoL scale, multi-item functional scales and symptom scales, and a scale regarding financial difficulties. The trial results demonstrated similar OS outcomes between the two groups. The authors chose to limit inclusion to the QoL analysis to institutions with at least 50% compliance and more than at least 35% during the follow-up period. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups, although those with the primary debulking group at baseline had more pain but less dyspnea.

In addition, the AURELIA trial studies the use of physician’s choice chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. Using the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire–Ovarian Cancer Module 28 (EORTC QLQ-OV28) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Ovarian Cancer symptom index (FOSI), the investigators demonstrated that with the use of bevacizumab, there was greater than 15% improvement in QoL and abdominal or gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms specifically. The CALYPSO trial was another European trial that randomized patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer to carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel. The QoL results, published in 2012, were generated by the EORTC QoL-QC30 questionnaire and OV28 ovarian cancer module. In this trial, patients treated with carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin had improved QoL scores and fewer cancer- and chemotherapy-related symptoms. This study, although designed as a noninferiority trial, did suggest that improved outcomes with the experimental arm were not at the expense of decreased QoL

Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer

Although patients with cervical cancer may present with pelvic pain or bleeding (or both) in more advanced stages, cervical cancer may also be detected based on screening tests alone. The usual treatment involves surgery for early stage followed by possible radiation, chemotherapy, or both for high-risk cases versus chemotherapy and radiation alone for more advanced stages. Patients with cervical cancer present with a unique set of symptoms, side effects from treatment, and socioeconomic issues not seen in patients with ovarian cancer. For example, these women have a lower median age at presentation; this group also has a larger percentage of Latina or nonwhite patients and a larger percentage of lower income patients. Furthermore, the chemotherapy and specifically the radiation received by these women produce such symptoms as sexual dysfunction and urinary and bowel dysfunction that perhaps affect women in unique ways.

In the measurement of QoL for cervical cancer, there are, similar to ovarian cancer, two tools that are most widely used, the FACT-Cx and the QLQ-CX24. The FACT-Cx is composed of the same physical, social, functional, and emotional well-being subscales as the FACT-G but in addition it has a seven-item scale for concerns related specifically to cervical cancer. These concerns involve vaginal discharge, bleeding, odor, narrowing or shortening, constipation, and dysuria. The GOG has published studies in advanced cervical cancer that have used the FACT-Cx. These patients have a poor median survival time, typically less than 6 months, and therefore it is still of debate whether or not treatment is futile in this setting. This is especially of concern in such advanced cancer when symptomatology can be debilitating and further aggressive treatment perhaps does more harm than good. This is an ideal patient population to study QoL because if QoL decreases with treatment, then one might argue against treatment in a disease in which OS is so poor.

In 2006, GOG protocol 169 was published by McQuellon et al. and reported QoL endpoints in a randomized trial that compared cisplatin versus cisplatin plus paclitaxel in advanced cervical cancer (see Table 20.5 ). Despite the impressive deficits in QoL compared with the general population, these two treatment regimens did not differ with regards to QoL. The cisplatin and paclitaxel arms did demonstrate improvements in response rate and PFS; therefore, the QoL data help to promote this regimen. In 2005, the QoL data from GOG 179 were published by Monk et al. This randomized trial studied cisplatin as compared with cisplatin and topotecan in advanced or recurrent cervical cancer cases. The FACT-Cx was used to document QoL between these two regimens in addition to exploring its relation to prognosis. There were statistical differences in QoL between the two regimens, but of interest was the relationship of the FACT-Cx to OS. As the FACT-Cx score increased, so did OS, and this was statistically significant. Finally, in GOG protocol 204, which studied multiple platinum-doublets in this population, it demonstrated again no difference in QoL scores between these regimens. The QoL data were published in 2010, and there were no reported differences among the four regimens. In 2015, Penson et al. reported the QoL results of GOG protocol 240, which introduced bevacizumab into the standard chemotherapy treatment of advanced or recurrent cervical cancer. Using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Cervix Trial Outcome Index (FACT-Cx TOI), there were no significant differences in QoL. Thus, despite improved PFS and OS, this did not necessarily translate into improved QoL. The FACT-Cx TOI in this analysis was associated with survival in that for every increment of 10 on the QoL score, hazard of progression or death was also incrementally affected. This same concept of QoL scores at baseline predicting outcomes in QoL analyses has been demonstrated in multiple investigations. In fact, Chase et al. did demonstrate that on several GOG cervical cancer trials, QoL measurement alone at baseline could predict the development of toxicity, including leukopenia, anemia, and GI toxicity. This association remained significant despite controlling for important patient characteristics such as performance status, age, and treatment type. Finally, in a randomized Japanese GOG study of carboplatin and paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in advanced or recurrent cervical cancer, the investigators used hospitalizations as an objective measurement of QoL. The carboplatin arm demonstrated less hospitalization time, which the authors suggest might equal improved QoL of that regimen.

Several other areas within the trajectory of cervical cancer have been explored in relation to QoL. These include preinvasive disease, surgery, radiation therapy, and survivorship. In 2013, a multicenter observational and cross-sectional study of 842 women in the United Kingdom was published. This study included women without dysplasia and genital warts as well as a spectrum of preinvasive cervical and vulvar disease. QoL assessment indicated a significant negative impact of these diseases on psychosocial well-being, including sexual functioning. Of note, anxiety and depression as well as pain were particularly noteworthy in women with genital warts. These effects on QoL not only persist throughout treatment but are also demonstrated in survivorship. For example, several studies have indicated that long-term effects can include worsening lymphedema and bowel, genitourinary, and sexual function after completion of multimodality treatment including chemotherapy or radiation. In addition, psychosocial functioning is affected in the long term. This prompted researchers to evaluate a program of telephone counseling for cervical cancer survivors. A total of 204 patients were randomized to telephone counseling versus usual care. This study not only demonstrated improvements in depression, gynecologic, and cancer-specific concerns in the intervention group but also demonstrated positive effects on biomarkers for psychosocial stress, with decreased levels of cytokines such as various interleukins. The hope is that research will continue to demonstrate improvements in patient-reported outcomes that can be objectively measured by biomarkers of stress and that ultimately this can link to clinical outcomes.

Quality of Life in Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer usually presents with vaginal bleeding and at an early stage. Treatment is surgical and occasionally involves postoperative chemotherapy, radiation, or both. Likely because of the less invasive or aggressive treatment, with the majority of patients presenting at an early stage, there are not as many studies that focused exclusively on QoL in patients with endometrial cancer. A Cochrane review published in 2012 but edited in 2015 included trials in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. Of the 14 randomized trials reported, no QoL results were identified and thus analyzed . In fact, in the GOG, there are only two published reports of QoL in patients with endometrial cancer, and there has yet to be an endometrial cancer–specific subscale incorporated into this research. In 2007, Bruner et al. published the results of the QoL components of GOG protocol 122, which compared whole-abdominal irradiation (WAI) and combination chemotherapy in advanced patients with endometrial cancer (see Table 20.5 ). In this study using the FACT-G in addition to the Fatigue Scale (FS), Assessment of Peripheral Neuropathy (APN), and Functional Alterations due to Changes in Elimination (FACE), QoL was measured before and after therapy. The WAI arm suffered greater deficits in the FS and FACE scores, but these scores somewhat improved over the varying time points. Conversely, the neuropathy scores were worse in the chemotherapy arm. Interestingly, the FACT-G scores did not differ between the two arms at any time point. The data generated in this study provide patients with the risks and benefits of each therapy and can perhaps shed light on whether QoL concerns in patients can overshadow the potential survival benefits of one modality.

In 2009, the QoL data were published from Europe’s Post Operative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Cancer (PORTEC-2) trial, in which patients received external-beam versus vaginal brachytherapy. This study used the QLQ-C30 measure in addition to subscales from the prostate cancer and ovarian cancer module, which included both bowel and bladder symptoms and sexual functioning symptoms from those scales. Despite the lack of significant differences between groups, there was a low level of sexual functioning in the two groups. The vaginal brachytherapy group overall reported better social functioning, fewer bowel symptoms, and less limitation in activity because of these side effects compared with external-beam radiation therapy. These results suggest the use of a treatment modality potentially as effective with less impact on QoL. In another GOG trial, Kornblith et al. published the results of the QoL component of the LAP-2 protocol, which compared patients undergoing laparoscopic staging versus laparotomy. The measures used included the FACT-G as well as a six-item scale consisting of items related to surgical side effects. In addition, they used the Physical Functioning Subscale of the Medical Outcome Study-Short Form (MOS-SF36. PF), which was developed to assess activities of daily living. The differences in QoL between these two groups favored the laparoscopy group, but this difference was modest. The authors very eloquently describe that to spare one patient the short-term QoL decline with laparotomy, 10 patients would have to be offered laparoscopy. In fact, only better body image persisted in the laparoscopy group at 6 months; all other measurements became comparable by that time point. QoL data can be complex in analysis and interpretation but can shed light on misconceptions regarding the benefits of one therapy or intervention over another.

More recently, several endometrial trials have focused on diet and exercise interventions focused on the prevalence of obesity in these patients. A systematic review and metaanalysis of body mass index and QoL in endometrial cancer included four studies with a total of 1362 patients. Indeed, obese endometrial cancer survivors demonstrate poorer physical, social, and role functioning compared with nonobese patients. One hundred patients with posttherapy endometrial cancer stage I to IIIA participated in a 6-month study of a home-based exercise intervention. In this study, the nonobese women demonstrated higher baseline QoL. Although the obese women had fewer improvements in QoL, both the obese and nonobese groups demonstrated some improvements in QoL with this exercise intervention over the period of 6 months.

The SUCCEED trial looked at an intervention of self-efficacy, weight loss, and QoL in obese endometrial cancer survivors. This study included 75 women randomized to usual care versus an intervention. The intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in the Weight Efficacy Life-style questionnaire. Essentially, this questionnaire measures a patient’s ability to resist weight gain and maintain healthy lifestyle behaviors. However, the FACT-G differences (QoL measurement tool) between the groups were reported as minimal except perhaps in the fatigue domain. Future trials such as the feMMe or the REWARD trial will look at the incorporation of the intrauterine device, weight loss interventions, and/or metformin in low-risk endometrial cancer patients.

Management of Common Physical Symptoms

Even when cancer can be treated effectively and a cure or life prolongation achieved, there are always physical, psychosocial, or spiritual concerns that must be addressed to maintain function and to optimize the QoL. Symptoms are a reminder to the patient and caregivers of the cancer and the potentially devastating effects of treatment. Symptoms related to cancer and its treatment have not attracted much notice in the past when patients and physicians alike felt that pursuing them might detract from the “real” goal of controlling the tumor. Consequently, symptoms have been taken for granted by the medical profession. Successful and appropriate management of physical symptoms can allow the care team to focus on the psychosocial closure of life and provide the patient an opportunity to participate more fully in the decisions of care and to rebuild or establish stronger relationships with family, friends, and coworkers.

Many physicians and nurses find symptom management in patients with advanced disease to be a frustrating experience because the symptoms may persist or progress. Although the symptoms are not always completely controlled, acknowledgment of the problem and working toward its relief offer invaluable support to the patient. Reliance on medical and drug therapies has been the traditional method to control symptoms. There is increasing recognition that nonpharmacologic approaches have significant benefits for individual patients. Nontraditional approaches such as acupuncture, biofeedback, aromatherapy, massage, and herbal medicine may have a role in the management of symptoms. Each of the following four physical symptoms is addressed in detail: fatigue, pain, nausea and vomiting, and diarrhea and constipation.

Fatigue

Fatigue is perhaps the most common symptom experienced by patients with gynecologic cancers. Fatigue is the most prevalent (60%–96%) and one of the least understood symptoms that affect cancer patients. Several factors are implicated in the causes of fatigue, for example, anemia, pain, nutrition, insomnia, cognitive dysfunction, and psychological distress. Fatigue has been reported by gynecologic patients as severe, distressing, and uncontrollable. Unfortunately, cancer-related fatigue is not relieved by rest and might not improve posttherapy. Patients have identified fatigue with cancer as the major obstacle to normal functioning and good QoL. Although almost a universal symptom of patients undergoing primary antineoplastic therapy or treatment with biologic response modifiers, it is also extremely common in populations with persistent or advanced cancer. Perhaps this is the result of inadequate attention on the part of health care professionals coupled with patients’ reluctance to discuss their fatigue.

Given the prevalence and impact of cancer-related fatigue, there have been remarkably few studies of the phenomenon. Its epidemiology has been poorly defined, and the variety of clinical presentations remains anecdotal. Perhaps this is secondary to the inability of fatigue to be measured in any way other than subjectively. The existence of discrete fatigue syndromes linked with predisposing factors or potential etiologies has not been confirmed, and clinical trials to evaluate putative therapies for specific types of cancer-related fatigue are almost entirely lacking.

Patients and practitioners can generally differentiate the “normal” fatigue experienced by the general population from the clinical fatigue associated with cancer or its treatment. The term “asthenia” has been used to describe fatigue in oncology patients but has no specific meaning apart from the more common term. This condition is inherently subjective and multidimensional. Typically, it develops over time and is characterized by diminishing energy, mental capacity, and the psychological condition of cancer patients ( Table 20.6 ). It is also linked with lethargy and malaise in the revised National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria. These classifications may enhance awareness of fatigue and improve reporting of the condition.

The following symptoms commonly present almost daily during the same 2-week period in the past month:

Plus five (or more) of the following:

|

When fatigue is primarily related to a treatment, there is generally a clear temporal relationship between the condition and the intervention. In patients receiving cytotoxic chemo-therapy, for example, it often peaks within a few days and declines into the next treatment cycle. During the course of fractionated radiotherapy, it is often cumulative and may peak over a period of weeks. Occasionally, it persists for a prolonged period beyond the end of chemotherapy or radiation treatment. The relationship between fatigue and demographic characteristics, physiologic factors, and psychosocial factors is not well defined. The specific mechanisms that precipitate or sustain the syndrome are unknown. Fatigue may present a final common pathway to which many predisposing or etiologic factors contribute ( Table 20.7 ). The pathophysiology in any individual may be multifactorial. Proposed mechanisms include abnormalities in energy metabolism related to increased nutritional requirements (eg, caused by tumor growth, infection, fever, or surgery), decreased availability of metabolic substrate (eg, caused by anemia, hypoxemia, or poor nutrition), or the abnormal production of substances that impair metabolism or normal function of muscles (eg, cytokines or antibodies). Other proposed mechanisms link fatigue to the pathophysiology of sleep disorders and major depression. Further research is necessary to determine mediating mechanisms and optimal interventions.

Physiologic

Psychosocial

|

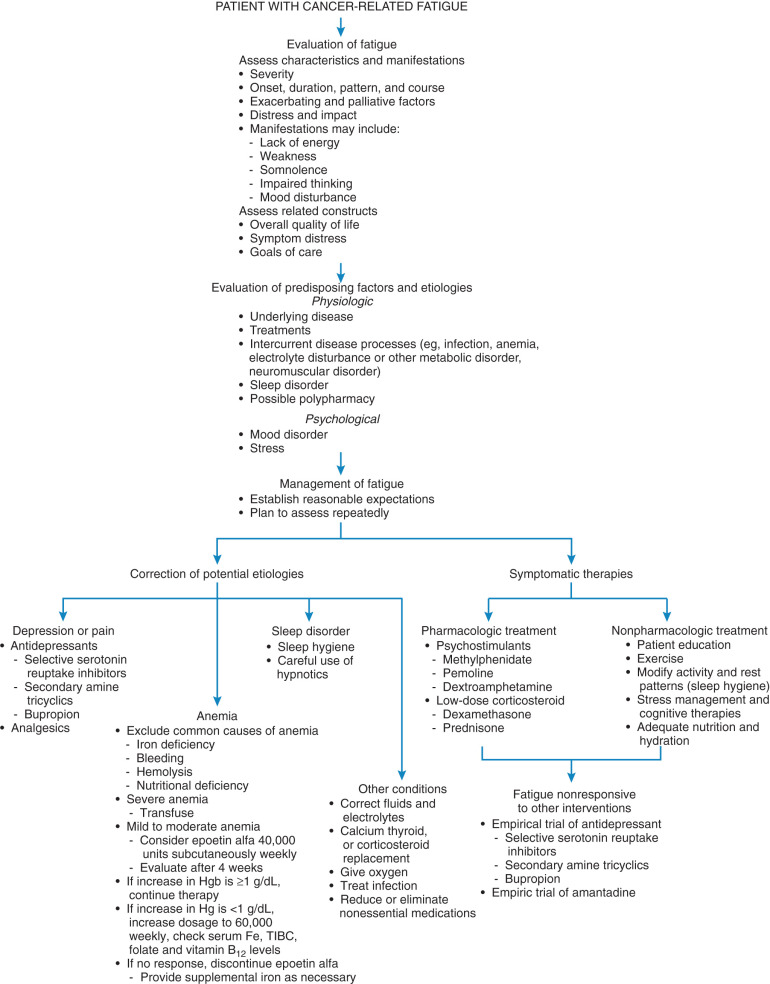

A detailed characterization of fatigue combined with an understanding of the most likely etiologic factors is necessary to develop a therapeutic strategy ( Fig. 20.1 ). The initial approach to fatigue should involve a screening tool. The recommended screen for cancer-related fatigue begins with a simple question: How would you rate your fatigue on a scale of 0 to 10 over the past 7 days? The score generated from this scale can drive the approach to treatment. A score of 0 to 3 is considered mild, 4 to 6 moderate, and greater than 6 severe. Those in the moderate to severe range should be evaluated immediately, but mild fatigue may be reevaluated. Evaluation of fatigue can then be approached differently depending on the patient’s being in active treatment, remission, or the end of life. Patients screening positive for moderate to severe fatigue should undergo a comprehensive assessment includes the description of fatigue-related phenomena, a physical examination, and a review of laboratory and imaging studies that may allow a possible hypothesis concerning pathogenesis, which, in turn, may suggest appropriate treatment strategies. Patients may describe fatigue in terms of decreased vitality or lack of energy, muscular weakness, dysphoric mood, insomnia, impaired cognitive functioning, or some combination of these disturbances. Although this variability suggests the existence of fatigue subtypes, this has not yet been confirmed. Regardless, the patient’s history should clarify the spectrum of complaints and attempt to characterize features associated with each component. This information may suggest specific causes (eg, depression) and influence the choice of therapy. Neurologic and psychological evaluation may also help further clarify potential causes of fatigue in some patients. Other characteristics are similarly important. Onset and duration, for example, distinguish acute and chronic fatigue. Acute fatigue of recent onset is anticipated to end in the near future. Chronic fatigue is persistent for a prolonged period (weeks to months or longer), and it is not expected to remit in a short time. Patients perceived to have chronic fatigue typically require more intensive evaluation as well as a management approach focused on both short- and long-term goals. Other important descriptors of fatigue include the severity, daily pattern, course over time, exacerbating and palliative factors, and associated distress. An assessment of cancer-related fatigue should also include consideration of broader concerns, including global QoL, other symptoms, and disease status. Fatigue may be only one of numerous factors that influence QoL. Among these factors are progressive physical decline, psychological disorders, social isolation, financial concerns, and spiritual distress. Optimal care of the cancer patient includes a broader assessment of these factors and should be directed toward maintaining or enhancing QoL. Successful strategies should ameliorate fatigue within a broader approach of patient care. Evaluation of the patient regarding the nature of fatigue, options for therapy, and anticipated outcomes is an essential aspect of the therapy. Unfortunately, results of a patient survey indicate that patients and their oncologists seldom discuss fatigue.

An initial approach to cancer-related fatigue includes efforts to correct potential etiologies, if possible and appropriate. This may include elimination of nonessential centrally acting drugs, treatment of a sleep disorder, reversal of anemia or metabolic abnormalities, or management of major depression. Referring to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the approach to pain, emotional distress, anemia, and nutrition may prove helpful. Perhaps sleep disturbances, interventions aimed at increasing activity levels, and the management of comorbidities may be more straightforward. Many of these initial interventions are relatively simple and pose minimal burdens to the patient, health care provider, and caregiver.

In general, education and counselling are advised in the initial treatment of cancer-related fatigue. Patients and family may be requested to document fatigue levels in a diary or on a scale and to describe associations or exacerbations and timing of the symptom. Similar to the approach to urinary incontinence, patients may be counseled toward behavior modifications or adjustments to help avoid this symptom such as eliminating nonessential potentially “tiring” behaviors that may call for unnecessary expenditure of energy. Conversely, increasing physical activity has been proposed as a treatment for cancer-related fatigue. A Cochrane analysis demonstrated improvements in fatigue with an exercise intervention. Adherence to the US Surgeon General’s recommendations for 30 minutes of exercise on most days of the week may thus be advisable for cancer patients in recovery. Physical therapy referrals should be made in certain patients, and caution with activity should be obvious in certain patients such as those with bone metastasis, neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, or active infection. Therapies such as massage, acupuncture, or psychosocial interventions are also described in the NCCN guidelines.

In patients with fatigue-associated major depression, treatment with an antidepressant is strongly indicated. As many as 25% of cancer patients develop major depression at some point during their illnesses. Patients at greatest risk are those with advanced disease, uncontrolled physical symptoms (eg, pain), or a previous history of a psychiatric disorder. Although the relationship between depression and fatigue is not well understood, they often occur together and both adversely affect QoL. Despite the high prevalence in the cancer population, depression is often underdiagnosed and consequently undertreated. A trial with an antidepressant is usually warranted in a patient with fatigue associated with any significant degree of depressed mood and similarly can be therapeutic when concurrent anxiety or pain exists. In addition, brief, focused psychological counseling can be helpful for several reasons when a mood disorder (eg, depression or anxiety) and a physical symptom (eg, pain or fatigue) co-occur. First, counseling offers the patient an opportunity to identify and express her fears, which are often driving the depressed or anxious mood. Second, the depressed or anxious mood can exacerbate existing physical symptoms such as pain. Therefore, provision of counseling has the dual benefit of reducing the mood disorder, which by extension reduces fatigue and pain. Third, brief, focused counseling can offer the patient important behavioral modifications such as time and energy management strategies that permit and teach the patient to conserve energy physically and emotionally for the priorities in their life. This is useful to address the practical challenges associated with fatigue and pain management.

Anemia may be a major factor in the development of cancer-related fatigue. Anecdotally, transfusion therapy for severe anemia has often been associated with substantial improvement in fatigue. Compared to other cancers, gynecologic cancers are especially known for being associated with severe anemia, with hemoglobin levels less than 9.9 g/dL in many cases. Not only does anemia have a significant correlation with poor performance status, but it may also be implicated in tumor sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy. It has been suggested that an optimal oxygen level for tumors to respond to therapy is reflected by a hemoglobin level between 12 and 14 g/dL. However, recent data of increased risk of thrombotic event associated with hemoglobin level higher than 12 g/dL should be taken into consideration.

New data demonstrate the association between chemotherapy-induced mild to moderate anemia and both fatigue and QoL impairment. For example, combined data from 413 patients and three randomized placebo controlled trials of epoetin alfa, the recombinant form of human erythropoietin (EPO), reveal that treated patients experienced a significant increase in hematocrit, a reduced need for transfusion, and a significant improvement in overall QoL. Patients with an increase in hematocrit of greater than 6% also demonstrated significant improvement in energy level and daily activities. Additional studies in patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy for various gynecologic tumors confirm that epoetin alfa has positive effects on hemoglobin levels. Two large, prospective, randomized, multicenter community trials have demonstrated that patients experience significant improvement in energy levels, activity level, functional status, and overall QoL when epoetin alfa is administered as an adjunct to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Blood transfusion is an option for the treatment of cancer-related anemia; however, transfusions are associated with poor outcomes and QoL caused by infections, allergies, or dependence on medical centers. For those reasons, many practitioners rely on growth factors, including epoetin alfa (rHuEPO—Epogen or Procrit) or darbepoetin alfa (Aranesp), to treat anemia. Kurz et al. concluded that rHuEPO increases hemoglobin levels and decreases transfusions in patients with gynecologic malignancies undergoing polychemotherapy without compromising QoL. It has even been suggested that rHuEPO may be given prophylactically in older patients (>65 years) and those with baseline hemoglobin levels of less than 10.5 g/dL who are going to be given chemotherapy consisting of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Although Aranesp has a longer half-life and therefore may be given less frequently, there are few clear advantages compared with Procrit. Unfortunately, this therapy is not without risks, and there are concerns that the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is increased for these patients. Results from meta-analyses from 2008 to 2013 indicated an association between increased risk of thrombotic events and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) usage with statistically significant risk and odds ratios ranging from 1.48 to 1.69. The increased risk for thromboembolism in patients with cancer became a black box warning in the updated Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labels and subsequently as part of the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). The increase FDA restrictions stemmed from eight randomized studies showing a decrease in OS or decreased locoregional disease control with EPO usage, including a cervical cancer study. More recently, research has shown that survival may be decreased in women receiving rHuEPO for correction of anemia for hemoglobin levels over 12 g/dL. Therefore, currently, patients with cancer may be counseled about the risks and benefits of the use of growth factors for the correction of anemia.

The NCCN and ASCO guidelines recommends that EPO should not be recommended to patients who are receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy with curative intent. Patients who are undergoing palliative treatment may receive EPO under REMS guidelines and with the informed consent of the patient. Many of the pharmacologic therapies for fatigue associated with medical illness have not been rigorously evaluated in controlled trials. Nonetheless, there is evidence to support the use of several drug classes. Psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine, have been well studied for the treatment of opioid-related somnolence and cognitive impairment and depression in elderly and medically ill patients. There are no controlled studies of these drugs for cancer-related fatigue, but empiric administration may yield favorable results in some patients. The national guidelines, however, are cautious in their suggestion of these interventions.

A clinical response to one drug does not necessarily predict a response to the others, and sequential trials may be needed to identify the most beneficial therapy. Methylphenidate has been more extensively evaluated in the cancer population than other stimulant drugs and is often the first drug to be administered. It is available in a chewable formulation that can be absorbed through the buccal mucosa for patients who are unable to swallow or take oral medications.

Adverse effects associated with the psychostimulants include anorexia, insomnia, tremulousness, anxiety, delirium, and tachycardia. To ensure safety, slow and careful dose escalation should be undertaken to minimize potential adverse effects. A regimen of methylphenidate, for example, usually begins with a dose of 5 to 10 mg once or twice daily (morning and, if needed, midday). If the drug is tolerated, the dose is increased. Most patients appear to require less than 60 mg/day, but some require much higher doses.

Extensive anecdotal observations and very limited data from controlled trials support the use of low-dose corticosteroid therapy in fatigued patients with advanced disease and multiple symptoms. Dexamethasone and prednisone are most commonly used. There have been no comparative trials.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, secondary amine tricyclics (eg, nortriptyline and desipramine), and bupropion are sometimes associated with the experience of increased energy that appears disproportionate to any change in mood. For this reason, these agents have also been tried empirically in nondepressed patients with fatigue. Given the limited experience in the use of these drugs for this indication, an empirical trial should be considered only in severe and refractory cases.

Amantadine has been used to treat fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis, but it has not been studied in other patient populations. This drug is usually well tolerated, and an empirical trial may be warranted in selected patients with severe refractory cancer-related fatigue.

Nonpharmacologic approaches for the management of cancer-related fatigue are supported mainly by favorable anecdotal experience ( Table 20.8 ). Patient preferences should be considered in the selection of one or more of these approaches. In particular, sleep hygiene principles should be tailored to the individual patients and might include the establishment of a specific bedtime, awake time, and routine procedures before sleep. Patients should also be instructed to avoid stimulants and central nervous system (CNS) depressants before going to sleep. Whereas regular exercise performed at least 6 hours before bedtime may improve sleep, napping in the late afternoon or evening may worsen it.

Patient Education

Exercise

Modification of Activity and Rest Patterns

Stress Management and Cognitive Therapies

|

Cancer and its treatment can also interfere with dietary intake. With aggressive approaches to management, the patient’s weight, hydration status, and electrolyte balance should be monitored and maintained to every extent possible. Regular exercise may improve appetite and increase nutritional appetite. Referral to a dietitian for nutritional guidance and suggestions for nutritional supplements may be useful.

The NCCN cancer-related fatigue guidelines were recently updated. This update includes further emphasizing the incorporation of fatigue as a cancer patient’s “vital sign.” Specific attention should now be paid toward improving sleep hygiene and enhancing the education of family members on cancer-related fatigue. In summary, the strategy aimed at combating fatigue should include physical activity, psychosocial interventions (ie, mindfulness-based therapy), nutrition counselling, and sleep interventions. Pharmacologic interventions such as psychostimulants can be used, but particular attention toward medications to address comorbidities, sleep, pain, anemia and mood is considered important.

Pain

Cancer pain can be managed effectively through relatively simple means in up to 90% of the 8 million Americans who have cancer or a history of cancer. Unfortunately, pain associated with cancer is often undertreated. Although cancer pain or associated symptoms cannot always be eliminated, proper use of available therapies can effectively relieve pain for most patients. Management of pain extends beyond pain relief and encompasses the patient’s QoL and the ability to work productively, to enjoy recreation, and to function normally in the family and society.

State and local laws often restrict the medical use of opioids to relieve cancer pain, and third-party payers may not reimburse for noninvasive pain control treatments. Thus, clinicians should work with regulators, state cancer pain initiatives, and other groups to eliminate these health care system barriers to effective pain management ( Table 20.9 ).

|

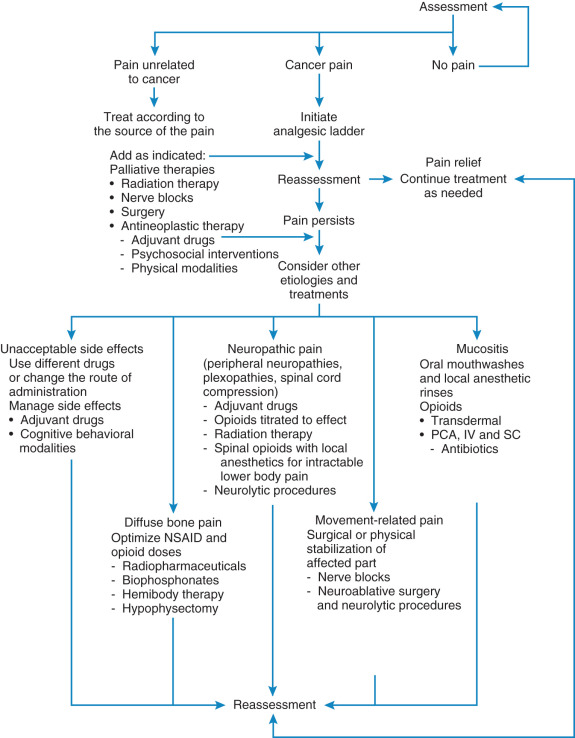

Flexibility is the key to management of cancer pain. Thorough discussions with the patient and their families encouraging them to be active in pain management are critical ( Table 20.10 ). Patients often need reassurance to report pain because effective treatment strategies exist. Failure to assess pain is a critical factor leading to undertreatment. Thus, a simple screening tool should be used to inquire about the patient’s pain level. This is described as “universal screening” by the NCCN. The goal of the initial assessment of pain is to characterize the pain by location, intensity, and etiology. This can be accomplished through a detailed history, physical examination, social assessment, and diagnostic evaluation. The mainstay of pain assessment is patient self-reporting. To enhance pain management across all settings, clinicians should teach patients to use pain assessment tools in their homes. Clinicians should listen to the patient’s descriptive words about the quality of the pain, inquiring about its location, severity, and aggravating or relieving factors and the patient’s cognitive response to the discomfort. Finally, goals for pain control should be clear with active engagement of the patient in the decision process. Continued assessment of cancer pain is crucial. Changes in pain patterns and the development of new pain should trigger diagnostic evaluation and modification of the treatment plan. Persistent pain indicates the need to consider other etiologies (eg, related to disease progression or treatment, and alternative—perhaps more invasive—treatment; Fig. 20.2 ). Pain related to an oncologic emergency should be addressed immediately. This includes pain resulting from a bone fracture or impending fracture, brain or epidural metastases, infection, or obstructed or perforated viscous.

|

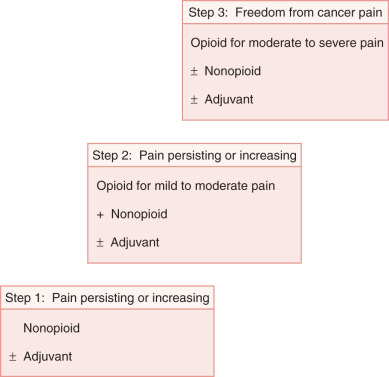

Drug therapy is the cornerstone of cancer pain management. It is effective, relatively low risk, and inexpensive and usually works quickly. Even within the same family of analgesic drugs, individual variations in tolerability and side effects are well recognized. Recommendations for pharmacologic therapy begin with the World Health Organization (WHO) ladder ( Fig. 20.3 ), a three-step hierarchy for analgesic pain management. Substitution of drugs within a category should be tried before switching therapy. The simplest dosage and schedule as well as the least invasive pain management modality should be attempted first. For mild to moderate pain, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (WHO ladder step 1) are often effective (see Table 20.10 ). When pain persists or increases ( Table 20.11 ), opioids can be added (WHO ladder step 2). Moderate to severe pain requires opioids of higher potency and dose (WHO ladder step 3) ( Table 20.12 ). Dosing should be on a regular schedule (ie, “by the clock”) to maintain a level of drugs that would help prevent the recurrence of pain. Ask for patient and family cooperation in establishing the effective level when administering medications to prevent long-term cancer pain on an around-the-clock basis with additional doses (“as needed” and usually required).

| Medications | Common Proprietary (Trade) Name | Usual Daily Dose (Adults) | Usual Daily Dose or Maximum Dose (Adults) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage and Route | Frequency | |||

| Acetaminophen | Tylenol, others | 325–650 mg PO | q4h | Immediate release: 3250 mg ER: 3900 mg |

| 650–1000 mg PO | qid | |||

| 650 mg PR | q4h | |||

| SALICYLATES | ||||

| Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) Same for buffered and enteric-coated oral formulations | Others | 600–1000 mg PO 300–600 mg PR | qid q4h | 4000 mg |

| Magnesium salicylates | Doan’s, others | 650 mg PO | qid | 4000 mg |

| Choline magnesium trisalicylate | Trilisate | 500–1000 mg PO 750–1500 mg | tid bid | 4000 mg |

| Diflunisal | Others | 500–750 mg PO | bid | 1500 mg |

| Salsalate | Disalcid | 750–1500 mg PO | bid | 3000 mg |

| PROPIONIC ACID DERIVATIVES | ||||

| Fenoprofen | Nalfon, others | 200–600 mg PO | qid | 3200 mg |

| Flurbiprofen | others | 50–75 mg PO | qid | 300 mg |

| Ibuprofen (OTC and Rx) | Motrin, Advil, Midol, others | 200–800 mg PO | qid | 3200 mg |

| Ketoprofen | Others | 25–75 mg PO 200 mg ER PO | tid–qid daily | 300 mg 200 mg XR |

| Naproxen | Aleve, Anaprox Naprosyn, EC-Naprosyn, Midol, Pamprin, others | 220–500 mg PO 750–1000 mg ER PO | bid–tid daily | 1500 mg 1000 mg ER |

| Oxaprozin | Daypro, others | 600–1200 mg PO | Daily | 1800 mg |

| ACETIC ACID DERIVATIVES | ||||

| Diclofenac | Voltaren, Voltaren-XR, Cataflam, Flector (transdermal), others | 50–75 mg PO 100 mg–XR 1%–3% patch, Gel, cream, solution (TDS) | bid-tid Daily–bid bid | 200 mg (PO) 32 g/day total to affected area(s) |

| Indomethacin | Indocin, Indomethacin ER | 25–50 mg PO 75 mg ER PO 50 mg PR | tid–qid bid bid–tid | 200 mg (both PO and PR) 150 mg ER |

| Sulindac | Others | 150–200 mg PO | bid | 400 mg |

| Tolmetin | Others | 400–600 mg PO | tid | 1800 mg |

| PYRANOCARBOXYLIC ACID | ||||

| Etodolac | Others | 200–400 mg PO 400–600 mg ER PO | tid–qid Daily–bid | 1000 mg 1200 mg ER |

| PYRROLIZINE CARBOXYLIC ACID | ||||

| Ketorolac | Sprix (intranasal), Others | 10 mg PO 15.75 mg/nostril 15–30 mg IM/IV | qid tid–qid qid | 40 mg 126 mg (intranasal) 120 mg–IM/IV |

| FENAMATES (ANTHRANILIC ACIDS) | ||||

| Meclofenamate | Others | 50–100 mg PO | tid–qid | 400 mg |

| Mefenamic acid | Ponstel, others | 250 mg PO | qid | not established |

| ENOLIC ACID DERIVATIVES | ||||

| Meloxicam | Mobic, others | 7.5–15 mg PO | daily | 15 mg |

| Piroxicam | Feldene, others | 10-20 mg PO | daily | 20 mg |

| NAPHTHALAKANONE | ||||

| Nabumetone | Others | 1000–2000 mg PO | daily | 2000 mg |

| COX-2 SELECTIVE AGENT | ||||

| Celecoxib | Celebrex, others | 50–200 mg | daily-bid | Not established |

* Most nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs have negligible hepatic metabolism, except for etodolac, ketorolac, nabumetone, oxaprozin, and meloxicam. Celecoxib and mefenamic acid undergo metabolism via cytochrome P450 2C9 isoenzymes. Excretion is via the kidney, primarily as metabolites. Sulindac and nabumetone are inactive prodrugs converted by the liver to active metabolites

| Medication | Proprietary (Trade) Name | Usual Starting Dose for Moderate to Severe Cancer Pain in Adults ≥50 kg of Body Weight | Usual Starting Dose for Moderate to Severe Cancer Pain in Adults <50 kg of Body Weight | Approximate Equianalgesic Dosing of Opioid Analgesics in Adults § | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Parenteral | Rectal | Oral | Parenteral | Rectal | Oral | Parenteral | Rectal | ||

| Codeine | 15–60 mg q4h | NA | NA | 0.5–1 mg/kg q4h | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Codeine combination products | Tylenol #2, #3, #4; others | 1–2 tablets q4h (maximum, acetaminophen 4000 mg/day) | NA | NA | Codeine: 0.5–1 mg/kg q4h Acetaminophen: 10–15 mg/kg q4h | NA | NA | Per codeine recommendations above | ||

| Hydrocodone | Hysingla ER (24 h) Zohydro ER (12 h) | 20 mg/day or 10 mg bid | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 mg | NA | NA |

| Hydrocodone–acetaminophen combination products | Vicodin, Lorcet, Lortab, Norco others | 1–2 tablets q4h (maximum, acetaminophen 4000 mg/day) | NA | NA | Hydrocodone: 0.135 mg/kg q4h; acetaminophen: 10–15 mg/kg q4h | NA | NA | 20 mg | NA | NA |

| Hydrocodone–ibuprofen (200-mg) combination products | Vicoprofen, Xylon, others | 1 tablet q4h (maximum, ibuprofen 3200/day) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 mg | NA | NA |

| Fentanyl | Duragesic (TDS); Sublimaze, others (IV); (Fentora [[buccal]; Actiq [lozenge]; Lazanda [intranasal]; and Abstral, Subsys [SL]— for breakthrough pain only ) | Buccal: 100 mcg/dose, MRx1 Lozenge: 200 mcg/dose, MRx1 SL: 100 mcg/dose, MRX1 | TDS: 25 mcg/h q 72h mcg/kg Intranasal: 100 mcg/spray, MRX1 in 2 h IV: 20–50 mcg/h | NA | NA | TDS: 12 mcg/h q72h for opioid-tolerant patients IV: 0.5 mcg/kg/h | NA | NA | 0.1 mg TDS and IV | NA |

| Hydromorphone | Dilaudid; Exalgo. other (ER tablet) | 2–4 mg q4h; 8 mg: ER daily | 0.2–0.6 mg q2h | 3 mg 6h | 0.03–0.08 mg/kg/dose q 4 hr (maximum, 5 mg/dose) | 1 mcg/kg/h | NA | 7.5 mg | 1.5 mg | 3 mg |

| Levorphanol | Others | 2 mg q6h | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 mg | 2 mg | NA | |

| Meperidine | Demerol, others | 50–150 mg q3h | 50–150 mg q3h 10 mg/h | NA | 1.1–1.5 mg/kg q 3 hr | 1.1–1.8 mg/kg q3h | NA | 300 mg | 75 mg | NA |

| Methadone | Dolophine, others | 2.5 mg q8h | 2.5 mg q8h | NA | 0.7 mg/kg q 4 hr | 0.7 mg/kg q4h | NA | 20 mg | 10 mg | NA |

| Morphine immediate release | Others | 5 mg q4h (tablet) 10 mg q4h (solution) | 10 mg q4hr; 1 mg/h | 10–20 mg q 4 hr | 0.02–0.5 mg/kg/dose q 4 hr | 0.05–0.1 mg/kg q4; 0.005 mg/kg/h | NA | 60 mg | 10 mg | 60 mg |

| Morphine ER | Kadian (ER); Avinza (ER); MS Contin (CR); others | MS Contin: 15 mg q12h Kadian: 30 mg/day Avinza: 30 mg/day | NA | MS Contin: 15–30 mg q 12 hr | 0.3–0.6 mg/kg/dose q 12 hr | NA | NA | 30 mg | NA | 30 mg |

| Oxycodone | Others | 10 mg q4h | NA | NA | 01–0.2 mg/kg q4h | NA | NA | 60 mg | NA | NA |

| Oxycodone ER | OxyContin, others | 10 mg q12h | NA | 10 mg q 12 h | NA | NA | NA | 20 mg | NA | 13 mg |

| Oxycodone combination products | Percocet, Xartemis XR (with acetaminophen 32 5 mg); oxycodone–ibuprofen 400 mg Others | 5 mg q6h (maximum, APAP, 4000 mg/day; ibuprofen 3200 mg/day) 1 tablet q 2h (XR) | NA | NA | 0.1–0.2 mg/kg q 4 hr | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oxymorphone immediate release | Opana, others | 10 mg q4h | 0.5 mg q4h | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6.6 | 1 | NA |

| Oxymorphone ER | Opana ER, others | 5 mg q12h | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.3 | NA | |

| Tapentadol | Nucynta | 50 mg q4h | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tapentadol ER | Nucynta ER | 100 mg q12 h | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tramadol | Ultram, Ultram ER, others | 25–50 mg q6 h (maximum, 400 mg/day); ER: 100 mg/day (maximum, 300 mg/day) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Tramadol 37.5 mg + acetaminophen 325 mg | Ultracet, others | 2 tablets q6h | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree