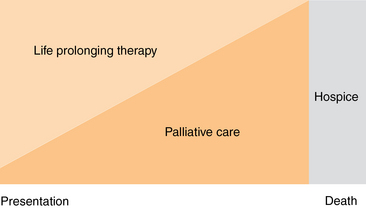

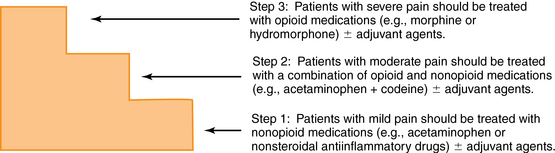

14 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the difference between palliative care and hospice. • Be familiar with the basics of pain management, including pain assessment and treatment. • Be familiar with the most common nonpain symptoms encountered in palliative care. • Create a basic framework for structuring conversations with patients and families for both breaking bad news and negotiating goals of care. At the turn of the twentieth century, the average life expectancy was 47,1 and people usually died suddenly as the result of trauma or infection. Over the last 100 years, however, advances in medicine such as antibiotics, improvements in nutrition, and developments in public health and safety have led to a greatly increased longevity such that the average life expectancy in 2001 was 77 years.1 As a consequence, the typical death is no longer a sudden or unexpected event. Rather, death today usually follows a lengthy period of chronic illness and functional dependency, such that chronic disease has become the leading cause of death. Evidence across all health care settings and disease categories demonstrates a high prevalence of physical, psychosocial, and financial suffering associated with serious illness and chronic disease. Partly in response to these changes, the field of palliative care has arisen to address the needs of patients and families that have not been well met by traditional medical care. Erroneously, the phrase palliative care is sometimes conceived as care that should be provided at the end of life when treatments directed at life prolongation are no longer effective and death is imminent. In actuality, palliative care is interdisciplinary care focused on improving quality of life for patients with serious illness and their family caregivers.2 It involves formal symptom assessment and treatment, aid with decision making regarding the benefits and burdens of various therapies, help in establishing goals of care, and collaborative and seamless transitions between models of care (hospital, home, nursing homes, and hospice) so as to provide an added layer of support to families and health care providers. Palliative care should be offered simultaneously with life-prolonging and curative therapies for persons living with serious illness (Figure 14-1). Figure 14-1 Palliative care is offered simultaneously with life-prolonging and curative therapies for persons living with serious, complex, and advanced illness. With this distinction in mind, it becomes clear that both patients presented in the opening case studies of this chapter can benefit from palliative care, but in different ways. Palliative care for Holly Johnson, with her advanced ovarian cancer and poor functional status, involves treating her symptoms (e.g., nausea, pain, depression), addressing her psychological and spiritual concerns, supporting her husband, and helping to arrange for her increasing care needs. The majority of this patient’s care occurs at home (with or without hospice) or in the hospital, and the period of functional debility is relatively brief (months). This differs from the care that Pam Rodriguez needs. Palliative care for this patient involves treating the primary disease process (her advanced heart failure); managing her multiple chronic medical conditions and comorbidities (diabetes, arthritis) and geriatric syndromes (cognitive impairment); assessing and treating the physical and psychological symptom distress associated with all of these medical issues; and establishing goals of care and treatment plans in the setting of an unpredictable prognosis. Additionally, the needs of her caregiver(s) are different from the needs of Holly Johnson’s caregiver(s). Ms. Johnson may have only a few months to live. The individuals caring for Ms. Rodriguez will most likely be her adult children who have their own families, work responsibilities, and medical conditions; these roles must be balanced with the months to years of personal care that they must provide to their aging parent. Like most elderly patients, both Ms. Johnson and Ms. Rodriguez can be expected to make multiple transitions across care settings (home, hospital, rehabilitation, long-term care),3 especially in the last months of life, and palliative care programs for older adults must ensure that care plans and patient goals are maintained from one setting to another. Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.4 Nearly 50% of severely ill hospitalized patients report that they have pain.5,6 Pain in older patients may be poorly controlled because they may underreport pain or may have difficulty communicating, and physicians may undertreat pain because of concerns about side effects in older patients.7 Neuropathic pain results from injury to actual nerve fibers as a result of compression, infiltration, or degeneration of neurons in either the peripheral or central nervous system.8 Patients often describe this pain as burning, tingling, stabbing, or electrical, and they tend to experience it as severe and constant. Examples of neuropathic pain include diabetic neuropathy, pain related to spinal stenosis, and pain resulting from trigeminal neuralgia. It is important to distinguish between the various types of pain because each is treated differently. Nociceptive pain is treated with, and often responds well to, traditional medications such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and opioids. Although neuropathic pain may respond to traditional analgesic agents, with this type of pain it is often necessary to use adjuvant agents such as tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, or local anesthetic agents.9–12 The treatment of pain begins with a thorough and complete assessment. The guiding principle of pain assessment is to ask patients about their pain and then believe their complaints. Several studies have shown that providers’ estimates of a patient’s pain severity are often lower than the patient’s self-report.13,14 Assessment of pain involves multiple components, and practitioners must consider each in order to best understand the nature and character of a patient’s symptoms. The first step of assessment is to inquire about the location of the pain as well as whether it radiates to any other part of the patient’s body. A description of the pain to determine if its origin is nociceptive, neuropathic, or some combination of both should be obtained as well as questions as to when the patient’s pain began; this information is required because chronic pain is often treated differently than acute pain. Additionally, it is important to ask what treatments (pharmacologic or otherwise) the patient has tried to relieve the pain as well as any factors that may exacerbate the pain. Temporal patterns of the patient’s pain should be understood. For example, joint pain that is relieved shortly after awakening is more likely to be from osteoarthritis than from rheumatoid arthritis. If patients do not freely offer information about these characteristics, then it is important to continue probing until the physician has a complete understanding of the nature of the patient’s pain and its associated factors. For a useful mnemonic device for assessing pain, see Box 14-1. Patients should be asked to rate their pain to better understand its severity as well as to give a baseline assessment to determine changes in the level of pain after treatment.7 The same scale should be used over time in each patient, so as to best be able to reliably track changes in pain over time. Patients can be asked to rate their pain in either words (none, mild, moderate, severe) or using a numeric scale (0 to 10 where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain experienced). They can also be shown a visual analog scale, where patients place a mark indicating their level of discomfort on a horizontal line representing a spectrum of pain (the leftmost portion of the line represents no pain, the rightmost, severe pain). Another visual scale often used includes a series of faces representing various states of emotion relating to the patient’s current level of pain. In addition to the assessment principles outlined above, a crucial component of pain in older adults relates to its impact on function. The presence of symptoms that limit patients’ activities of daily living (ADLs)15 should trigger physicians to focus on the home environment and may signal the need for additional home care services. In cases where the patient cannot provide a thorough history because of conditions such as dementia or aphasia, this information can be obtained from nursing staff and the patient’s family.7 The clinician’s physical examination should be used to confirm any suspicion generated during the history taking. Conditions to note include muscle spasm, gait impairment, abnormal joint alignments, and changes in skin color or integrity—to name just a few.16 Clinicians may assume that they cannot assess pain in individuals with cognitive impairment, but this is often not the case.17 Patients with cognitive impairment or aphasia are often able to give basic information if questions are asked in a yes/no format. In addition, physicians can use signs such as facial expressions (grimacing or frowning), diaphoresis, and changes in vocal patterns (e.g., increased moaning or changes in pitch) as signs that a patient may be in distress. Clinicians can also ask family members and paid caregivers to report their impressions of the patient’s pain as well. Unfortunately, clinical studies have shown that patients’ and family members’ ratings of pain are not always well correlated, with family members often underestimating the patient’s pain intensity.18–20 With this in mind, however, clinicians may be able to begin with the family’s assessment of the cognitively impaired patient and add to this the other visual and diagnostic clues discussed above to better estimate a patient’s level of pain. Older patients’ fear of addiction has also been shown to be one of many barriers to effective pain management.16,21 One way to counteract this barrier is to educate patients and their families about addiction and how it differs from tolerance and dependence. Tolerance is a pharmacologic phenomenon that refers to diminished analgesic effect of a constant dose of a medication after exposure over time.16 Tolerance routinely develops after patients receive opioid medications, and relates both to the analgesic properties of the medication (i.e., patients may need more of a medication over time to obtain the same analgesic effect) and to its side effects (e.g., patients will develop tolerance to the sedative effect after a short period of time). Typically when patients with cancer or other systemic diseases begin to need increasing doses of a medication, it is a result of progression of the underlying disease rather than the development of tolerance. Dependence refers to a biological phenomenon whereupon patients may develop withdrawal symptoms once the medication is discontinued.7 For example, patients who have been on chronic opioid therapy may experience diarrhea and a dramatic increase in their level of pain if the medication is abruptly halted. Addiction refers to continued use and seeking of a medication despite harm to self and others. This phenomenon is rarely seen in patients who are treated for chronic pain, and is seen no more often in patients with cancer than in the general population.22 One way to avoid this confusion is to avoid the use of terms such as narcotics and drugs because these words may be associated with societal stigmas. Clinicians must differentiate addiction from pseudoaddiction, a phenomenon in which patients exhibit drug-seeking behavior because of undertreatment of their pain. This is an iatrogenic phenomenon, and it will resolve itself when patients are given an adequate medication regimen with appropriate dosing intervals.23 The basic and most widely used approach to management of pain is illustrated by the World Health Organization’s “pain ladder”24 (Figure 14-2). Although originally developed to assist clinicians with assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer, the model can be extended to nonmalignant painful conditions in elderly individuals such as osteoarthritis or pathologic fractures resulting from osteoporosis. The first step, for patients with mild pain, encourages the use of nonopioid medications such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs with or without an adjuvant agent (see following section).25 If a patient’s pain increases to a moderate level or remains poorly controlled, the next step involves adding a weak opioid medication alone or in combination with the nonopioid (e.g., acetaminophen with oxycodone) with or without the use of an adjuvant agent. The third step, for patients with severe pain, advises the use of a strong opioid (e.g., morphine, hydromorphone) with or without an adjuvant. Recent evidence suggests that patients with moderate or severe pain, especially that related to cancer, may receive faster pain relief by being started on a strong opioid regimen immediately rather than progressing in such a stepwise fashion or employing weak opioids (e.g., codeine) or combination products.26,27 Figure 14-2 Schematic of levels of pain and appropriate medications to use at each step. (Adapted from World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer pain relief. Geneva: WHO; 1986, with permission.) Adjuvant agents are medications that can be combined with opioid therapies to either decrease the dose of medication needed or to avoid dose-related side effects. The term adjuvant refers to the fact that these medications are drugs with a primary indication other than pain, but they have analgesic properties in some painful conditions.12

Palliative care

What is palliative care?

Assessing and treating pain in older adults

Pain assessment

Treatment of pain

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Palliative care