pain management are delineated in The Joint Commission (TJC) standards. TJC standards focus on health care provider orientation, education, patient rights, patient education, and postoperative care and contain wording specific to pain management (TJC, 2012). In recent years, evidence-based recommendations, guidelines, and position statements for pain management have been developed by such groups as the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management (Horlocker et al., 2010), the American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN), and the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011). Additionally, the scope and standards of practice for pain management nursing were developed in a joint venture involving ASPMN and the American Nurses Association (ANA) and apply to both the nurse generalist and the nurse specialist in pain management. Institutional policies and procedures guide nurses through definitions, responsibilities, assessment and management expectations, and educational requirements for pain management. Influencing factors change as pain management practice evolves and new knowledge becomes available.

EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICE

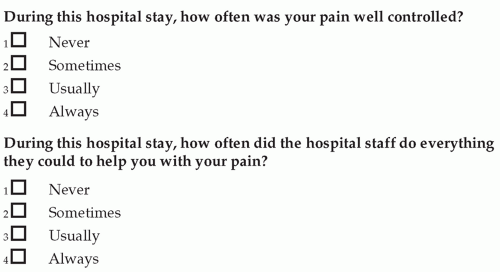

EVIDENCE FOR PRACTICEpain management for long bone fracture” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011). Another example is the time in minutes that it takes from the moment that a patient enters the emergency department until the patient receives an oral or parenteral pain medication. Patient satisfaction with pain management is an example of another outcome quality indicator. Two questions that all acute care patients are asked after discharge are illustrated in Figure 20-2. These originated from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, initiated as a requirement for hospitals receiving Medicare reimbursement. These questions and others are publicly available for use. The results from patient surveys are also available and grouped at the hospital level. Reviewing results for the hospital or unit may provide opportunities for improvement.

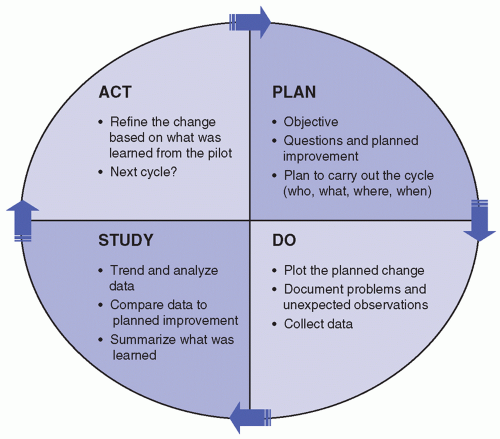

FIGURE 20-1 Plan, Do, Study, Act Cycle. (Adapted from Langley, G., Nolan, K. M., & Nolan, T. W. (1994). The foundation of improvement. Quality Progress, 27, 81.) |

TABLE 20-1 QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER FOR PLAN-DO-STUDY-ACT (PDSA) OR QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROCESS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

extent authorized by the state law or a state’s regulatory mechanism or federal guidelines and organizational policy” (Medscape, 2013).

Assessment

Intervention

Reassessment

care providers of the importance of listening to our patients and partnering as we design a pain management plan. The definition of pain from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recognizes the sensory and emotional components of pain as well as the fact that pain may exist without evidence of tissue injury. “Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage” (IASP Task Force on Taxonomy, 1994). These definitions lay the groundwork for insight into the phenomenon of pain and may serve to guide our treatments.

Systemic analgesics and adjuvant medications (administered orally, rectally, transdermally, intramuscularly, IV, subcutaneously, by continuous infusion, or by patient-controlled analgesia [PCA])

Intraspinal opioids, including epidural and intrathecal

Regional analgesia using local anesthetic agents

Topical anesthetic agents

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Electrical analgesia through transcutaneous electrical stimulation or electroacupuncture

Psychological analgesia in the form of hypnosis, relaxation techniques

The autonomic nervous system responds to acute pain by increasing the sympathetic drive. When the sympathetic drive is increased, there is an increase in heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, but there is also vasoconstriction, and a decrease in peristaltic action. This response is a protective mechanism that serves to create a flight-or-fight response. The cause of acute pain is usually known and persists until the underlying cause is resolved. Factors that influence postoperative pain may be found in Box 20-4.

and cancer (American Cancer Society, 2012) combined. In recent years, there has been a shift from the term “chronic” pain to “persistent” pain, to relieve patients of the stigmatization associated with chronic pain. Persistent pain may or may not have a known nociceptive input and has no autonomic response (Litwack, 2009; Rosner, 1996). Injury or disease may cause persistent pain, but it is perpetuated by factors that are seemingly unrelated or remote from the original cause (Turk & Okifuji, 2010). Persistent pain has been described using chronological markers of 3 to 6 months duration or it’s described as pain that extends beyond the expected period of healing. Recent conceptualizations of persistent pain characterize it as extending for a long period of time and/or represent low levels of underlying pathology that does not explain the presence or extent of the pain (Turk & Okifuji, 2010). Persistent pain is now thought of as a chronic disease and can be a result of central sensitization (Sluka, O’Donnell, Danielson, & Rasmussen, 2012).

Site, nature, and duration of the surgical procedure

Type of incision location

Degree of intraoperative trauma

Physiologic and psychological features characteristic of the patient

Preoperative education preparation

Amount of preoperative pain or past pain experiences

Presence of complications

Intraoperative management of pain

Anesthetic management before, during, and after surgery

Quality of postoperative care

PATIENT SAFETY

PATIENT SAFETYCare Policy and Research Acute Pain Guidelines. When a patient receives meperidine, the body creates a metabolite called normeperidine. As the administration of meperidine continues, the normeperidine accumulates, creating toxicity resulting in seizures (Latta, Ginsberg, & Barkin, 2002).

a specific number of respirations per minute (Pasero et al., 2011). Respiratory depression is caused by an accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood, which communicates with the brain (medulla oblongata) to slow respirations until the carbon dioxide level returns to normal. All opioids can depress brain stem-regulated ventilation, producing a dose-dependent reduction in respiratory rate (Yaney, 1998).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree